Introduction

Since the Supreme Court ruled affirmative action in college admissions unconstitutional last summer, the practice of giving the relatives of alumni special consideration in admissions—known as “legacy preferences”—has come under increased scrutiny. Critics say that the practice of legacy admissions is not meritocratic and disproportionately benefits white students from wealthy backgrounds. The U.S. Department of Education has opened a civil rights investigation into Harvard’s legacy admissions practice. Experts for the Plaintiffs in the Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) affirmative action case argued that Harvard and UNC could increase racial diversity if they abandoned legacy admissions, though the experts on the other side suggested the effects on diversity would be small at best. A recent study of a dozen highly selective, private, “Ivy plus” colleges found that legacy admissions are an important mechanism driving higher admissions rates among the richest applicants.

Most research and discussion about legacy admissions focuses on Ivy plus and other highly selective private colleges, but those institutions enroll only a small share of students. How widespread is the practice of giving special consideration to relatives of alumni in admissions? Is it common among public colleges, which should be equally accessible to all of a state’s residents?

In this report, we document the prevalence of legacy admissions, as reported by colleges, across higher education around the time of the SFFA decision. Legacy admissions were more often used at selective and private institutions, but a substantial minority of public and less selective institutions also considered legacy status in admissions. The use of legacy preferences appears to have been most common in the Northeast and South and least common in the West. There is substantial—but incomplete—overlap in the colleges that considered legacy status and those that practiced affirmative action (AA) prior to SFFA. A number of colleges, including some public colleges, said they considered relationships to alumni but not racial identity in admissions.

While most state flagships don’t consider legacy status in admissions, half have at least one scholarship opportunity that is catered to legacy students. Because the data are available with a lag, we do not know how many colleges have changed their legacy admissions policies in response to the Court’s decision on affirmative action, but press reports and our conversations with admissions representatives indicate that some colleges have changed course in the past few years, including at least five state flagships.

The effect of legacy preferences on who enrolls at a particular university may not be substantial overall. Many of the colleges that use legacy admissions are not that selective, and the scholarships for relatives of alumni are typically small. Still, even if the number of students directly displaced by legacies who had a leg up is ultimately not that large, the practice sends students the wrong signal about what’s important and is contrary to the mission of a public university. In a recent survey, half of first-generation college students said they thought legacy admissions practices may have hurt their chances. Perceptions of an unfair admissions process might also make some students less likely to apply or undermine the perceived legitimacy of higher education, though we did not find research on this topic.

Colleges practice legacy admissions for a variety of reasons

Legacy admissions began at Ivy League colleges in the early 1920s as part of an effort to keep Jewish immigrants out of elite, historically Protestant universities. Other colleges adopted the practice over time, though we do not know of data documenting the timing of changes in any detail. In the face of demographic change, legacy preferences will cause the composition of enrollment at a college to change less quickly than the composition of otherwise qualified applicants. This is why the practice worked to prevent a large increase in Jewish students in the early 20th century, and some have argued that it slowed the growth in representation of students of Asian descent in highly selective colleges today.

Colleges argue giving children of alumni preferential treatment in admissions promotes fundraising and alumni engagement. For example, in 2018, a Harvard committee charged with evaluating admissions policies voiced concern that eliminating legacy preferences would decrease alumni donations and involvement. They also argued that considering legacy status helps promote a sense of community and connection among Harvard alumni. While some research does substantiate the claim that legacy advantages increase donations, other evidence suggests that legacy preferences have little or no effect on fundraising. There’s limited research about the effects of legacy admissions on overall alumni engagement.

Colleges may also perceive that legacy students will be more familiar with the campus culture and more likely to participate in campus life. For example, in 2021, in consideration of reinstating legacy admissions, a Texas A&M Regent argued that children of alumni know “what they’re getting into. And that’s a big positive.” (Texas A&M did not reinstate legacy preferences.)

Finally, colleges might also use legacy preferences as part of a “yield management” strategy. A higher yield (the share of admitted students who enroll) means that the college has to admit fewer students overall to ensure that the appropriate number actually goes on to enroll. This translates to a lower admissions rate, which signals selectivity and can improve a college’s reputation. Colleges may take legacy status as a signal of interest, in which case admitting legacy students increases yield. And if those students are more likely to be willing to pay full tuition, that’s another benefit for the college.

Legacy admissions and race-based affirmative action

Unlike affirmative action, which was already banned in public colleges in nine states prior to the SFFA decision, there has been little legislative action against legacy admissions; in 2021, Colorado became the first state to ban the practice in public institutions. On March 8, 2024, Virginia became the second state to prohibit legacy admissions in public institutions. Some public colleges have reevaluated their legacy preferences following state-level affirmative action bans. The University of California system, the University of Georgia, and Texas A&M all eliminated legacy preferences shortly after they were prohibited from considering race in admissions decisions. Since the SFFA decision, a handful of both private and public colleges have announced that they will no longer consider legacy status in admissions. In a statement to CNN, the Wesleyan University president said that legacy preferences no longer seemed defensible in the absence of affirmative action.

Data on admissions practices

There are two publicly available data sources about legacy admissions prior to SFFA: the Common Data Set (CDS) and the federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), which collected legacy admissions information for the first time in 2022-23.

Many four-year colleges participate in the Common Data Set (CDS), an initiative of the College Board, Peterson’s, and U.S News to facilitate comparisons across colleges. Colleges report a range of institutional characteristics and information about their admissions process. The electronic data is reported and maintained by the College Board and not publicly available, but many colleges post the CDS on their website. We collected these publicly posted survey responses. In one section, colleges indicate whether they consider various factors in their admissions process, including “alumni/ae relationship” and “racial/ethnic status.” We collected these responses from recent years and merged the data with institutional characteristics from IPEDS and Barron’s college selectivity classifications. We used similar data in our analysis of the use of affirmative action.

The federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) recently began requiring colleges to report whether they consider legacy status. So far, they’ve published responses for the 2022-2023 academic year. We focus our analysis on the CDS data because we want to examine the overlap in the use of legacy preferences and affirmative action prior to SFFA, and the CDS includes both. However, we note that substantially fewer colleges reported considering legacy status in IPEDS than in the CDS. We contacted some colleges to investigate the source of these discrepancies. Reasons cited include accidental reporting for the wrong year and differences in interpretation among university administrators about what it means to “consider” legacy status and alumni relationships.

During our data collection, we discovered that some colleges offer scholarships for legacy students, which could have similar implications to legacy admissions but is not captured by either dataset on admissions practices. Collecting scholarship information for all colleges is prohibitively time-consuming, but we searched the websites of each state flagship for information about whether they have scholarships that are only available to legacy students (and whether they are for in-state, out-of-state students, or both). We also confirmed (via the admissions website, public statements, or by calling the college) the current status of legacy admissions at the state flagships, which we report on separately below.

Our data references years prior to SFFA (mostly for the 2021-22 academic year), meaning it doesn’t capture policy changes since SFFA. The data also do not indicate how much weight a college puts on legacy status or on race in its admissions process, only whether a college reported that they “considered” alumni relationships and/or race. Colleges with open or minimally selective admissions are much less likely to post CDS responses, and since their admissions processes are by definition not very competitive, whether they consider legacy status or race is less consequential for student outcomes. We therefore exclude colleges in Barron’s “Not competitive” category from our analysis. We have CDS data for colleges accounting for over 80% of enrollment in four-year colleges that are at least “Less competitive” according to Barron’s. It is worth noting that about 38% of first-year full-time college students attend community colleges or the “Not competitive” and open access four-year colleges that are excluded from this analysis.

For more information about the data, see the appendix.

Selective and private colleges were most likely to consider legacy status

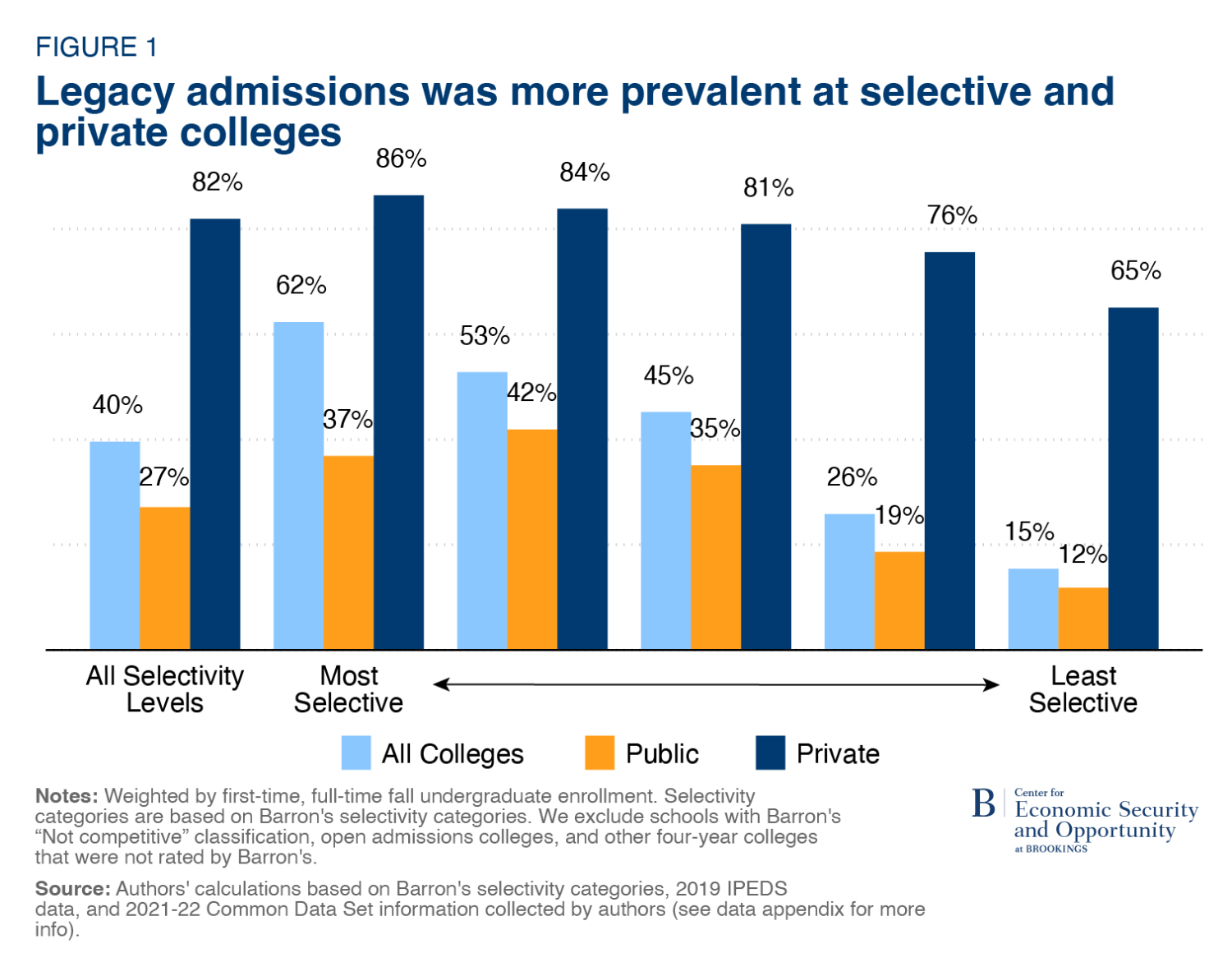

Figure 1 illustrates how legacy consideration varied by selectivity and whether a college is public or private. All of the results are weighted by first-time full-time enrollment. The Barron’s selectivity categories, arranged from most to least selective on the graph, are based on admissions rates and the standardized test scores, high school grades, and class rank of the incoming first-year class.

Overall, 40% of students attended colleges that practiced legacy admissions (the first, light blue bar), with this proportion significantly higher among private colleges (82%) than public colleges (27%). Among the most selective private colleges, 86% of students were enrolled at colleges that considered legacy status, compared to 65% among the least selective private colleges. Among the most selective public colleges, 37% of students were enrolled at colleges that considered legacy status, compared to 12% among the least selective public colleges.1

Selective colleges were more likely to consider both legacy status and race

Affirmative action may have historically offset some of legacy admissions’ negative effects on diversity. Given this possibility and the renewed interest in legacy preferences due to the demise of affirmative action, we explore the intersection between legacy admissions and affirmative action. Recall that the data we use here refer to admissions practices from before affirmative action was banned (usually 2021-22).2

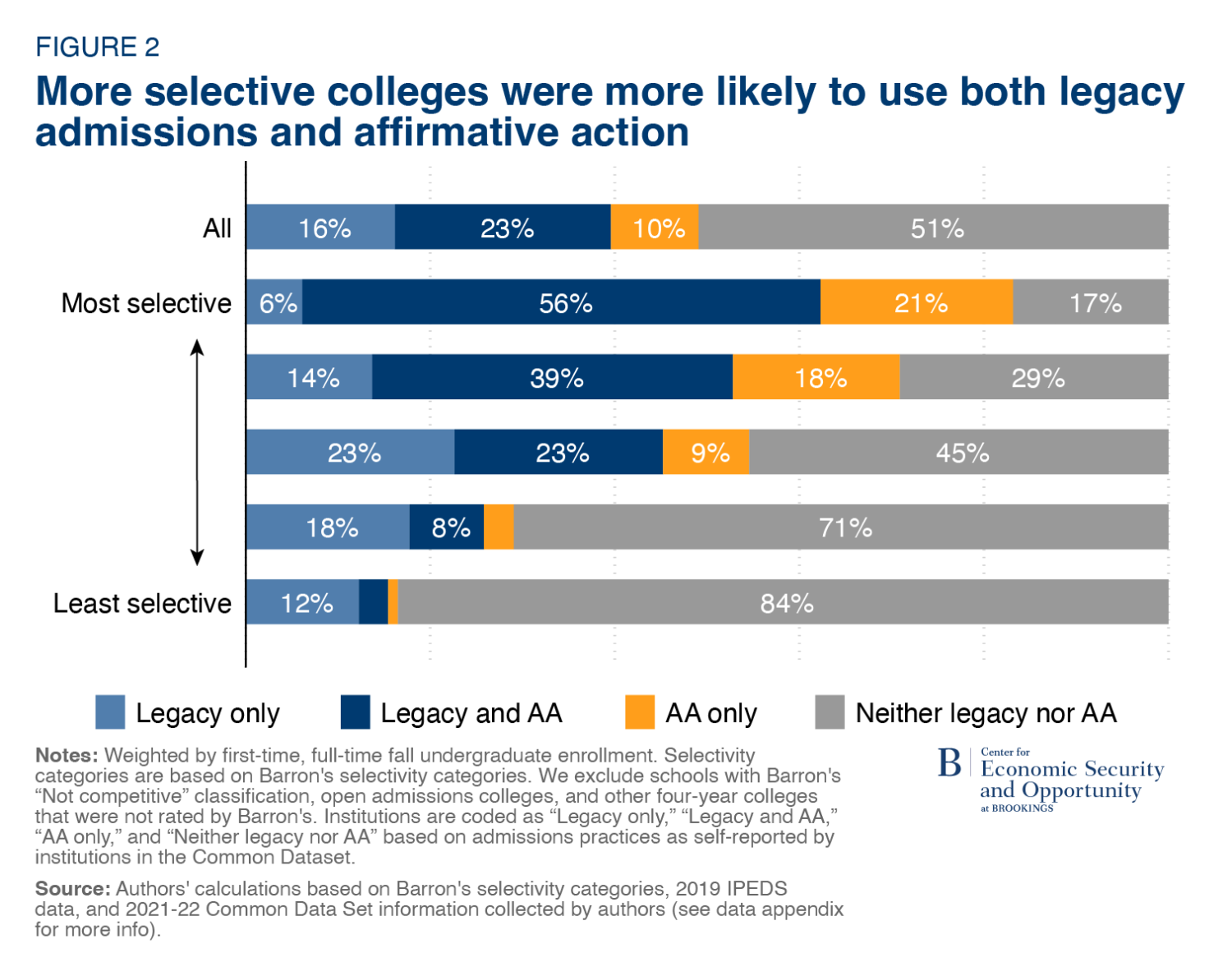

Figure 2 divides colleges into categories based on whether they considered legacy status, race, neither or both. The first bar shows the results for all four-year colleges that are at least somewhat selective in their admissions, according to Barron’s. Colleges that only considered legacy status account for 16% of enrollment, those that considered both legacy status and race account for 23% of enrollment, and colleges that only considered race account for 10% of enrollment; about half considered neither race nor legacy status.3

More selective colleges were most likely to consider both legacy status and race in admissions decisions, rather than just one or the other. At the highest selectivity level, more than half of students attended colleges that considered both legacy status and race, while 6% attended colleges that only considered legacy status. At the lowest selectivity level, 12% of students were enrolled in colleges that considered legacy status, and 3% of students were enrolled in colleges that considered both legacy status and race. If we use the data on legacy preferences from IPEDS instead of CDS, the pattern of results is similar, but the level of reported legacy use is lower (so the prevalence of AA only is higher).

Notably, affirmative action was more common than legacy admissions at more selective colleges, but legacy admissions were more common than affirmation action at less selective colleges.

Private colleges were more likely than public colleges to consider both legacy status and race

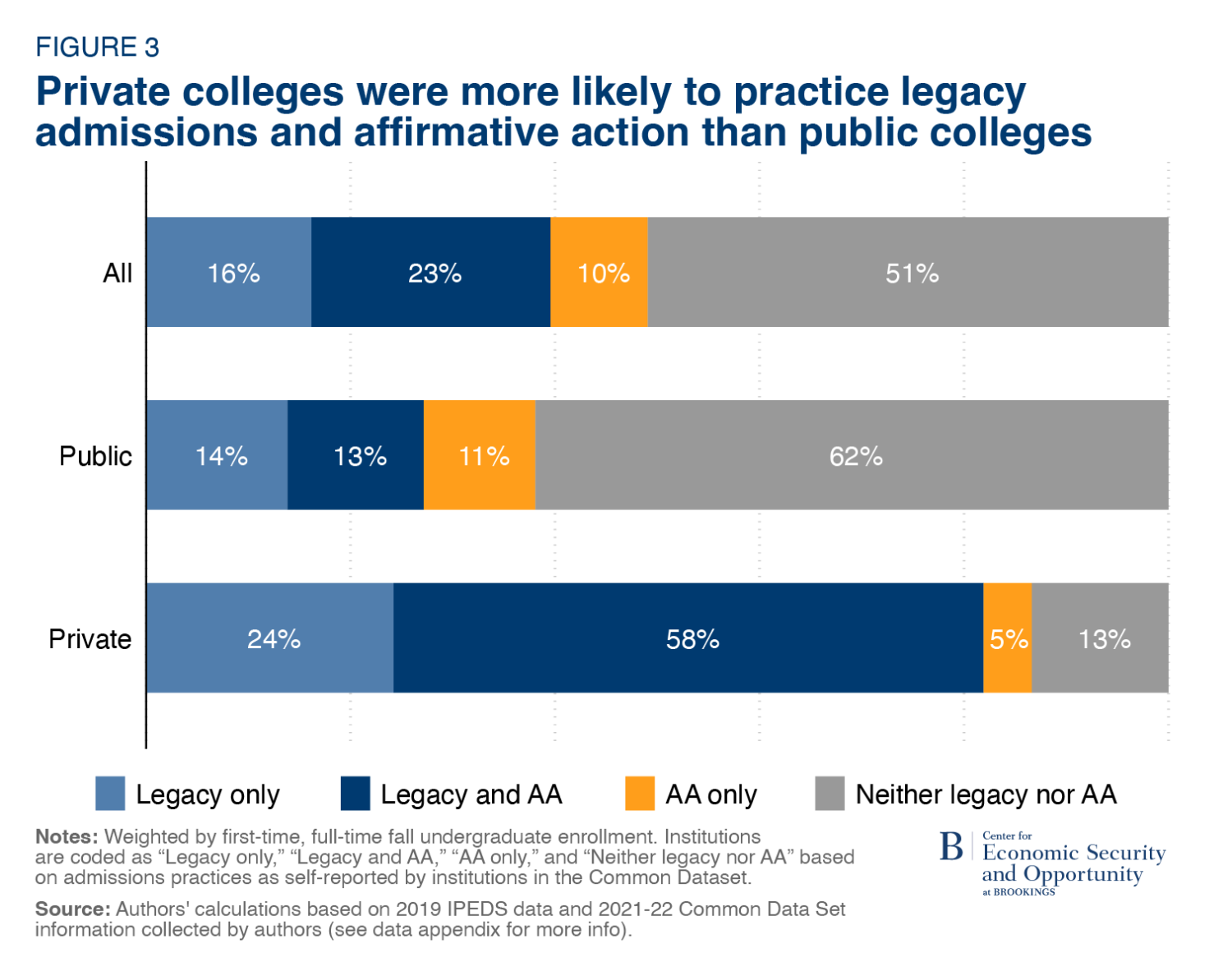

Private colleges were more likely than public colleges to consider both legacy status and race. Additionally, as highlighted in figure 3, private colleges that considered legacy status (the light blue and dark blue bars) were more likely to also employ affirmative action (just the dark blue bar) compared to public colleges that considered legacy status.

Among public colleges, 14% of enrollment was in colleges that only considered legacy status and 13% were in colleges that considered both legacy status and race. Among private colleges, 24% of enrollment was in colleges that considered only legacy status, while 58% were in colleges that considered both legacy status and race. Across both public and private colleges, legacy admissions were more common than affirmative action.4

Colleges in the Northeast were most likely to consider both legacy status and race

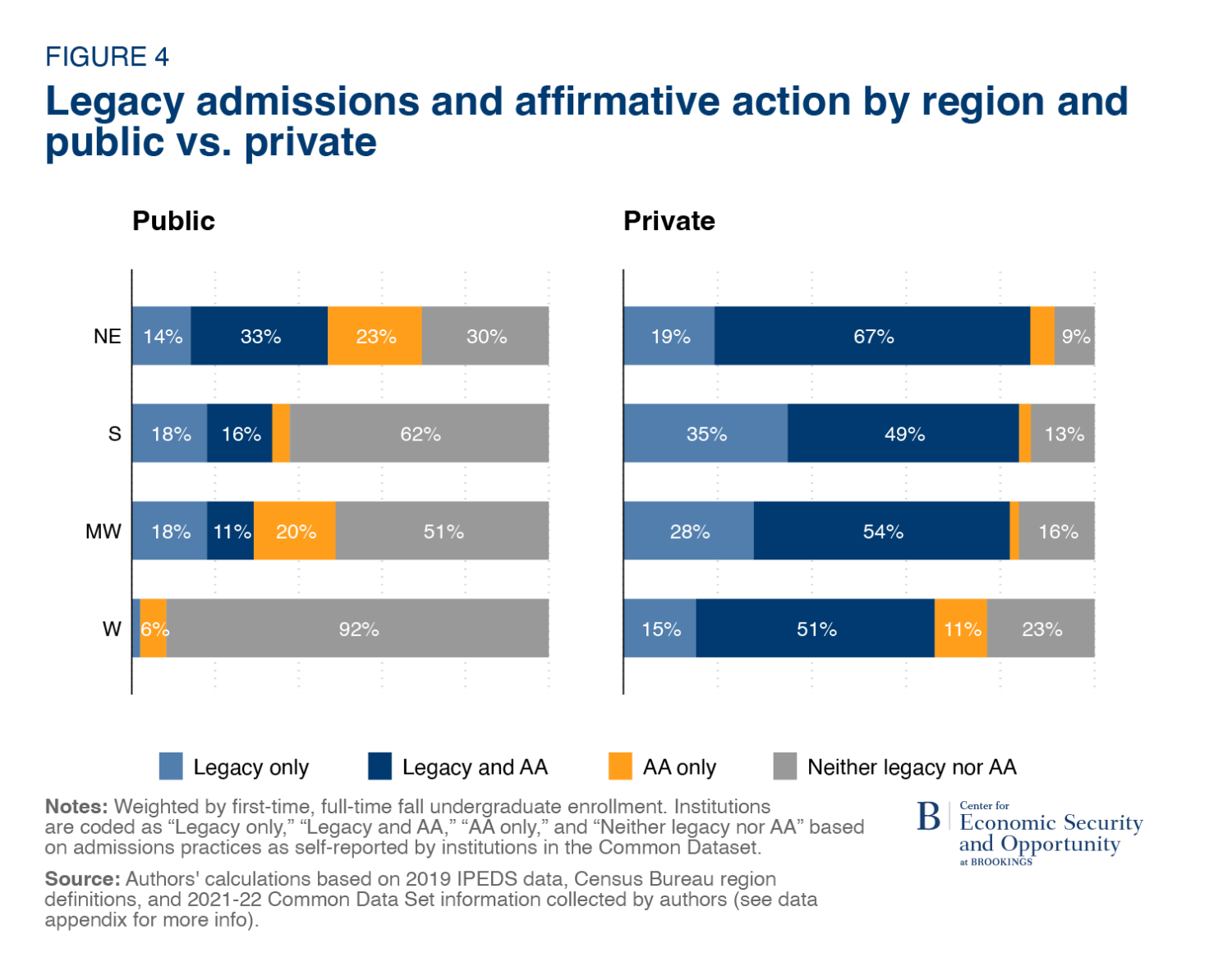

Figure 4 shows the intersection between legacy and race consideration by region (as defined by the Census) and whether a college is public or private. The regions are ordered from highest to lowest share using legacy admissions (the two shades of blue). Legacy admissions were most common in the Northeast (NE) and least common in the West (W), but there is significantly more regional variation among public colleges. Among public colleges, the total percentage attending colleges that considered legacy status ranged from 47% in the Northeast, to 2% in the West. Among private colleges, the percentage ranged from 86% in the Northeast to 66% in the West. Regions with higher rates of legacy admissions generally also had higher rates of colleges practicing both legacy admissions and affirmative action. As already illustrated in figure 3, private colleges were more likely than public colleges to practice legacy admissions in conjunction with affirmative action.5

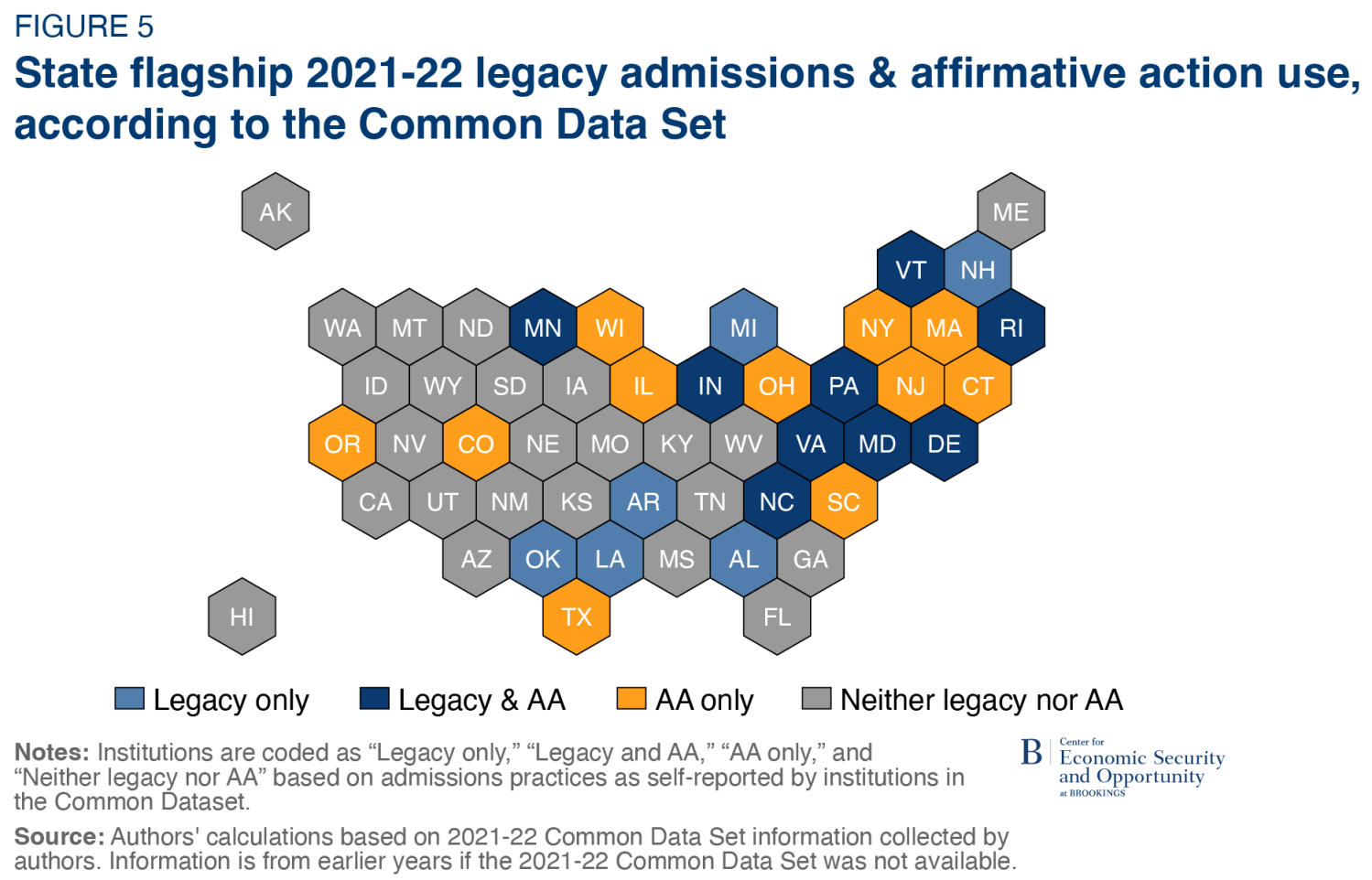

A substantial number of state flagships considered legacy admissions and race

Figure 5 focuses on public flagships—typically the most selective public universities in each state—showing which ones considered legacy status and race in admissions based on the CDS data from 2021-22. Some of these institutions reported a different legacy policy in IPEDS and/or changed their policy since we collected the CDS data; we report on the current status of legacy admissions at state flagships in Figure 6.

The regional variation among flagships generally aligns with the regional variation among all public colleges shown above. In the West, most state flagships considered neither legacy status nor race, except Oregon and Colorado, which both considered race but not legacy status. Farther east, both legacy and race consideration were more prevalent, with both most common in the Northeast. Of all flagships, 11 only considered race, nine considered legacy status and race, and six considered legacy status only. Affirmative action was more prevalent than legacy admissions among flagships, but still, 30% of public flagships considered legacy status.6

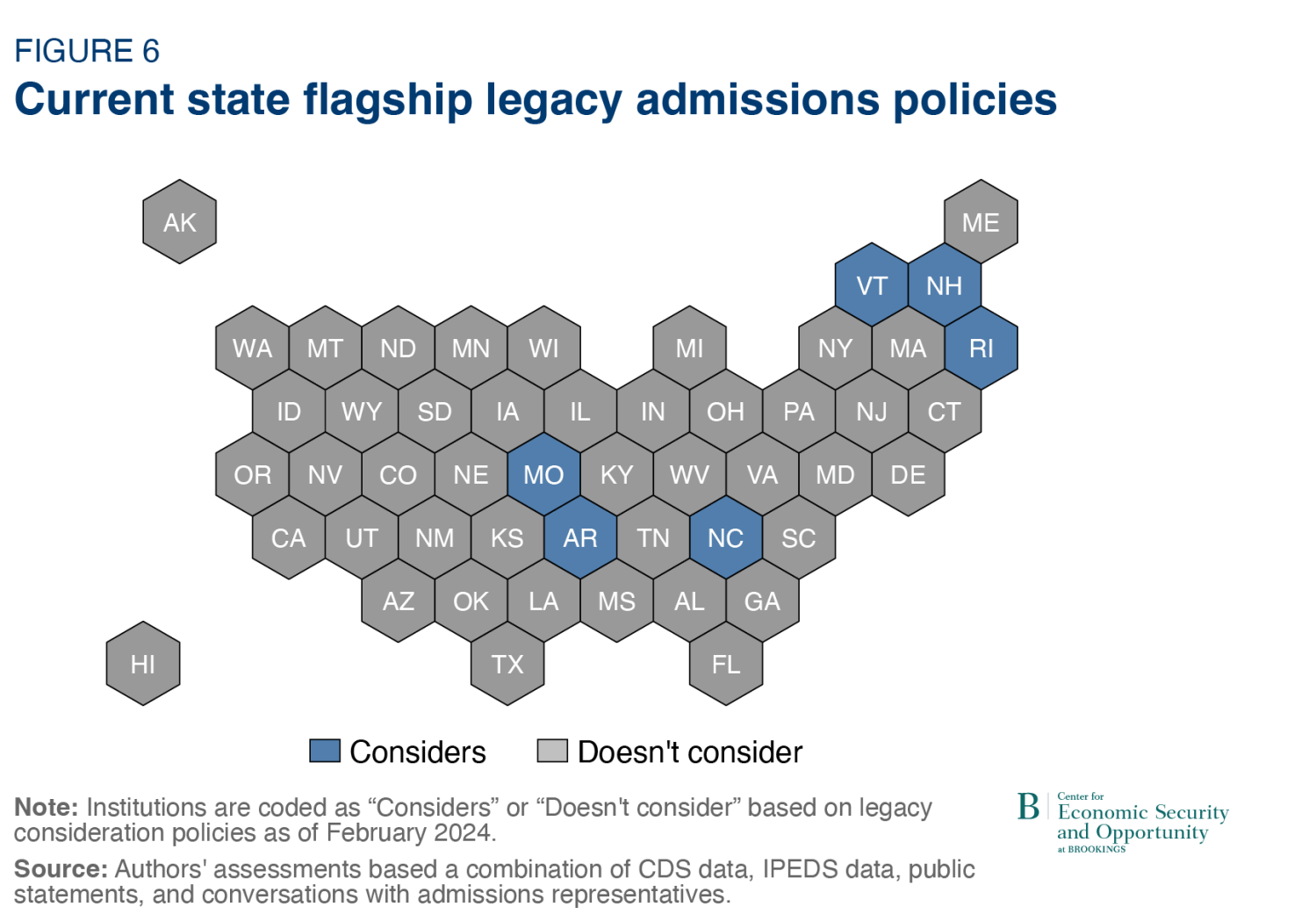

More than one in ten state flagships still consider legacy status

Figure 6 reflects our understanding of each state flagships’ current legacy consideration policy for future admissions cycles based on a combination of CDS data, IPEDS data, public statements, and conversations with admissions representatives.7 At least five state flagships have officially ended legacy preferences since 2020, and three have since SFFA.8 The University of Virginia is the most recent flagship to no longer consider legacy status—a change that came after the Virginia governor signed a bill on March 8, 2024 prohibiting legacy preferences at public colleges. The new law will take effect on July 1st and impact the 2024-2025 admissions cycle.

Six flagships currently report considering legacy status, compared to 15 based on CDS and pre-SFFA data. Part of this decline is because of actual policy changes, but some of the difference may also be due to changes in how universities communicate their admissions practices and/or mistakes in the CDS reporting. While legacy admissions prevalence has declined, over one in ten state flagships still consider legacy status. Granted, it remains unclear how much weight these flagships put on legacy status and how much it impacts admissions decisions.

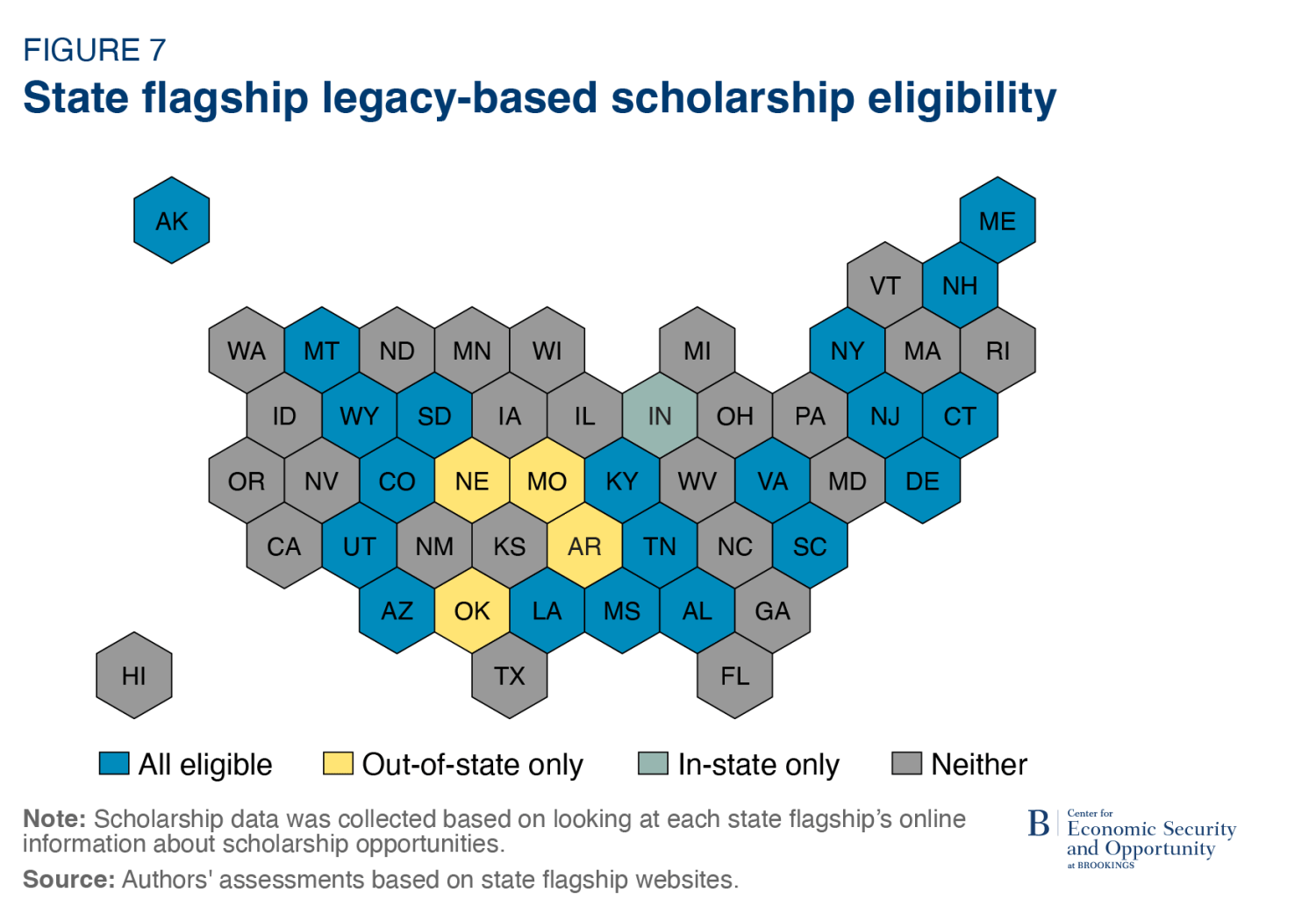

Legacy-based scholarships are common among state flagships

Even if public flagships don’t practice legacy admissions, there is another mechanism through which they can favor legacy students: scholarships. Based on our review of each state flagship’s online information about scholarship opportunities, we determined that half of all flagships have at least one scholarship catered to legacy students. These scholarships range from $500 per year (University of South Carolina) to over $10,000 per year at colleges such as the University of Nebraska. Most colleges that offer legacy-based scholarships provide them to both in-state and out-of-state students, although sometimes out-of-state students are eligible for more assistance than in-state students. Four state flagships only offer legacy-based scholarships to out-of-state students. For example, the University of Missouri offers up to $21,500 to out-of-state legacy students (contingent on these students meeting a GPA and test score threshold), and no legacy-based scholarships for in-state students. One flagship, Indiana University, restricts legacy-based scholarships to in-state students.9

Legacy-based scholarships are presumably designed to promote alumni engagement and loyalty. The University of Missouri website says that their legacy program was created to “support and recognize legacy students.” It’s possible that colleges see legacy-based scholarships as a strategy to attract talent likely to attend their university, particularly from out of state. However, scholarships and outreach efforts based on other qualifications may be a more effective and equitable recruitment tool.

Effects of ending legacy admissions on diversity and opportunity would probably be small

How much would ending legacy preferences in admissions affect diversity and opportunity in higher education? Above we show that among colleges that have at least somewhat selective admissions, those that said they considered alumni relations in admissions accounted for almost 40% of enrollment. But we cannot tell from these data how much weight these colleges place on legacy status. Studies do suggest that legacy applicants receive an admissions boost at some highly selective colleges, even after accounting for characteristics associated with being a legacy such as test scores, though the legacy boost at less selective institutions is almost certainly smaller.10

Even where legacy students receive a substantial admissions advantage, the effects on diversity may not be substantial. The study of Ivy Plus colleges, where the legacy bump is proportionally large, provides a useful benchmark.11 The authors estimate that eliminating legacy preferences would reduce the share of enrolled Ivy Plus students who come from the top 1% of the parental income distribution (incomes above $611,000) from 15.8% to 13.7% and increase the share from the bottom 60% (incomes less than $73,000) from 15.7% to 16.6%.12 Though this would represent a real opportunity for the approximately 200 lower-income students each year who would otherwise not have been enrolled, it would hardly represent a sea change in the composition of the Ivy (Plus) League.

The authors do not report on how this would change the racial composition of students, but the analysis suggests that the total number of admits that are attributable to legacy status is small, and swapping out a small number of students can only go so far in changing the composition of the student body.

Ivy Plus colleges also have very large endowments that support generous financial aid. This means that were the admissions office to swap out a legacy admit in favor of a lower-income student, that lower-income student would likely receive enough financial aid to attend. But many other colleges cannot afford to meet the full financial need of all their students (or do not choose to prioritize financial aid over other goals). Without additional financial aid, eliminating legacy preferences may just replace legacy students from privileged backgrounds with non-legacy students from privileged backgrounds.

The experience of Johns Hopkins University, which is highly selective but not an “Ivy Plus” college, also illustrates this point. The university eliminated legacy preferences in undergraduate admissions a decade ago, and representation of both lower-income and Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American students has increased substantially since then. But ending legacy preferences was only one piece of a larger effort which included more outreach and was supercharged by a $1.8 billion donation from alumnus Michael Bloomberg, about $300 thousand per undergraduate. The gift allowed the school to provide generous financial aid (loan-free) and admit students without regard to financial need. Even with the new funding and outreach, the university’s president and architect of the transformation worries it could be difficult to sustain progress on racial diversity in the face of the Court’s affirmative action ruling.

Conclusion

Considering family connections in admissions is straightforwardly un-meritocratic and contrary to the mission of a public college. It could send a signal to non-legacy and first-generation students that they are less welcome and perhaps shouldn’t even apply. Public support for ending legacy admissions is also strong: A 2022 Pew Research Center study found that 75% of Americans don’t believe legacy status should be considered in admissions decisions.

At the very least, colleges that consider legacy status should clarify their policies for potential applicants and families. Some colleges we examined, including state flagships, gave conflicting information about whether they consider family relations in different datasets. Some say legacy status is not considered on their website, but on the application, they ask if parents, grandparents, or siblings attended the college. This sends mixed signals and may erode trust at a time when higher education can hardly afford it.

These are among the many reasons that colleges should stop considering legacy status in admissions, or at least become more transparent about it. However, it should be understood by policymakers and university leadership that ending the practice will likely have only small effects on racial and socioeconomic diversity and would be unlikely to offset the effects of ending affirmative action at most colleges. Legacy admissions are just a small piece of a college admissions system that favors students from advantaged backgrounds in numerous ways. Much more central to that system is that, due to opportunity gaps across many domains, students from more privileged backgrounds are substantially better-prepared academically when they reach college application time. Addressing gaps in academic preparation as well as college affordability gaps is key to increasing representation of Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American students and those from lower-income families in four-year colleges.

Appendix

For this analysis, we combined newly collected college-level data from the Common Data Set (CDS) with the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Set (IPEDS) and selectivity ratings from Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges. In this appendix, we describe the data and analysis in more detail.

IPEDS Enrollment and Institutional Characteristics Data

We use the institutional characteristics and fall enrollment files of the Integrated Postsecondary Education Dataset (IPEDS), accessed through the Urban Economics Education Data Portal. We use data from the 2019-20 school year, prior to the COVID disruption.

Using institutional characteristics reported in IPEDS, we distinguish schools as either public or private institutions and classify schools by region based on the Census Bureau’s regional divisions. Additionally, we use the enrollment file to calculate full-time, first-time enrollment for each institution. We exclude “nonresident alien” enrollment from our analysis, restricting our sample to U.S. citizens and permanent residents.

Barron’s College Selectivity Data

We use Barron’s ratings data from Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges 2019. Barron’s selectivity index classifies U.S. four-year institutions based on admissions rate and enrolled students’ academic credentials. There are six main Barron’s selectivity categories, as well as an additional category that includes specialized schools such as health sciences and music schools. Barron’s includes a “plus” distinction for the most competitive schools within some of the selectivity categories, but we ignore this distinction for the purposes of our analysis. We exclude from our analysis schools in Barron’s least selective category, specialized schools, schools with an open admissions policy, and other schools unrated by Barron’s.

CDS Legacy Status and Race/Ethnicity Consideration in Admissions Data

We construct the variables on the consideration of legacy status and race/ethnicity in admissions based on our collection of Common Dataset (CDS) responses posted on colleges’ websites. To collect the CDS data, we created a list of all four-year institutions with institution size of at least 1,000 using the 2019 IPEDS data, plus smaller institutions with Barron’s classifications of “Competitive Plus” or higher. 13 We conducted a Google search for “[college name] Common Dataset 2021” and retrieved the CDS for the 2021-22 academic year when possible. If the 2021 file was not available, we retrieved the CDS for earlier or later years.14 Colleges with open or minimally selective admissions are much less likely to post CDS responses, and since their admissions processes are by definition not very competitive, whether they consider legacy status or race is less consequential for student outcomes. We therefore exclude colleges in Barron’s “Not competitive” category from our analysis. It is worth noting that about 27% of first-year full-time college students attend community colleges and 12% attend the not competitive and open access four-year colleges that are excluded from this analysis.

We are left with CDS data for 692 institutions, 689 of which have valid data for legacy consideration and 684 of which have valid data on whether they considered race or ethnicity in admissions. We manually code legacy consideration for two of the colleges with missing CDS legacy data and race/ethnicity consideration for one of the colleges with missing CDS race/ethnicity data based on policies we found on the college’s websites.

Appendix Table 1 shows the coverage of the data we collected, for the sample of four-year colleges with Barron’s ratings of at least “Less Competitive.”

Appendix Table 1: Coverage of Collected CDS Data

| Variable | Number of institutions | % of institutions | % of full-time first-time first-year enrollment |

| Found CDS | 692 | 54.6% | 81.0% |

| Non-missing legacy consideration Data | 691 | 54.5% | 81.0% |

| Non-missing race/ethnicity consideration data | 685 | 54.0% | 80.5% |

| Non-missing sample | 685 | 54.0% | 80.5% |

The CDS survey, a joint venture of the College Board, US News, and Peterson’s, asks a wide range of questions about academic offerings, student enrollment and persistence, the admissions process, student life, faculty, expenses, and financial aid. In the “Freshman Admissions” section of the survey, colleges are asked to indicate how important several factors are in admissions. The response options are “Very Important,” “Important,” “Considered,” and “Not Considered.” We code institutions as having practiced legacy admissions if they chose an option other than “Not considered” for “alumni/ae relationship.” Similarly, we code institutions as having practiced affirmative action if they chose an option other than “Not Considered” for “racial and ethnic status.”

IPEDS Legacy Status Consideration Data

IPEDS recently began requiring colleges to report whether they consider legacy status. So far, they’ve published responses for the 2022 – 2023 academic year, available from the National Center for Education Statistics. We focus our analysis on the CDS legacy consideration data because we want to examine the overlap in the use of legacy preferences and affirmative action prior to SFFA, and the CDS includes both. However, we note discrepancies between the IPEDS and CDS data about legacy preferences when applicable throughout the report.

Appendix table 2 shows the coverage of IPEDS legacy data versus CDS legacy data. IPEDS includes legacy data for nearly twice as many colleges than the CDS, but the colleges that have missing CDS data but non-missing IPEDS data have small enrollments on average. The CDS data covers 81% of full-time, first-year enrollment, compared to 99% for the IPEDS data.

Appendix Table 2: Coverage of IPEDS vs. CDS Legacy Data

| Variable | Number of institutions | % of institutions | % of full-time first-time first-year enrollment |

| IPEDS | 1,224 | 96.5% | 98.8% |

| CDS | 691 | 54.5% | 81.0% |

Additionally, substantially fewer colleges report considering legacy status in IPEDS than in the CDS, even when reporting for the same year. There are 684 colleges for which legacy consideration data is available in both the CDS and IPEDS. Of these colleges, 191 report a legacy consideration policy in IPEDS that conflicts with their CDS response. Notably, our CDS data is primarily from 2021 – 2022, and the IPEDS data is from 2022 – 2023. To investigate whether the data discrepancies stem from changes over time, we collected and compared 2022 – 2023 CDS reports to the 2022 – 2023 IPEDS data. We were able to retrieve 2022 – 2023 CDS responses for 139 of the 191 colleges with data discrepancies. Of these 139 colleges, 114 reported a policy in their 2022 – 2023 CDS response that conflicts with their IPEDS response. Of the colleges where the CDS and IPEDS data disagree, 79% report considering legacy status in the CDS but not in the IPEDS database.

We contacted some colleges to investigate the source of these discrepancies. Reasons cited include accidental reporting for the wrong year and differences in interpretation among university administrators about what it means to “consider” legacy status and alumni relationships.

Data on State Flagship Legacy Consideration and Legacy Scholarships

While fully investigating legacy consideration at all colleges with conflicting IPEDS and CDS data is prohibitively time-consuming, we confirmed (using the admissions website, public statements, or by calling the college) the current status of legacy admissions at state flagships that reported considering legacy status in their most recent CDS response and/or responded differently on their CDS and IPEDS. We separately report on these findings. Additionally, we searched the websites of each state flagship for information about whether they have scholarships that are only available to legacy students (and whether they are for in-state, out-of-state students, or both).

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- Using IPEDS data, the relationship between selectivity and legacy admissions is similar, but the correlation is less clear for public colleges (and the overall level of reported legacy admissions use is lower in IPEDS).

- We use the most recent CDS report available for colleges that didn’t publish their 2021-22 CDS responses.

- Note that the overall prevalence of affirmative action reported here is higher than in our earlier report on affirmative action. This is because we exclude colleges in Barron’s “Not competitive” classification and colleges with missing legacy data from this analysis. These excluded colleges are less likely to have considered race in admissions.

- This general pattern remains when using IPEDS data, but there are lower levels of reported legacy consideration, particularly among public colleges.

- In the IPEDS data, the regional trend among public colleges is similar. Among private colleges, the trend differs, with legacy admissions most common in the South, second most common in the Northeast, and least common in the Midwest.

- This percentage is slightly lower (18%) according to IPEDS data.

- Ten state flagships had discrepancies between what they reported to IPEDS and what they reported in the CDS (two only reported considering legacy status in IPEDS and eight only reported considering legacy status in the CDS). Our coding for these colleges is based on phone conversations with admissions representatives. For the remaining flagships without data discrepancies, we coded colleges based on information in their 2023–2024 CDS along with public statements and conversations with admissions representatives.

- The Michigan, Colorado, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Virginia state flagships have officially stopped considering legacy status since 2020. The Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Virginia flagships changed their policy after the SFFA decision.

- We classify Indiana University (IU) as offering legacy-based scholarships to in-state students, but IU does also offer scholarships that both in-state and out-of-state students are eligible for if they are the child or grandchild of an IU Alumni Association staff member or child of an alumni chapter leader.

- The fact that many colleges report conflicting data to different sources may suggest it is not weighted heavily in the process (and this is what some colleges we talked to said). Plus, many colleges that use legacy admissions are not highly selective, so legacies may not need a leg up to be admitted; the practice may be part of a yield management strategy or a signal of support to their alumni. Analysis in the Plaintiff’s expert report in the UNC case suggests legacy preferences were much more important for out-of-state applicants (which is a small share of all applicants); this may be true at other state flagships.

- The authors use data from three of the Ivy Plus colleges (they do not identify which), and these calculations extrapolate those findings to all twelve Ivy Plus colleges. According to our data and their website, MIT does not consider legacy status in admissions.

- Note that the admissions bump for legacy applicants can be large without it resulting in a large number of additional admits if legacies are a small share of the applicant pool (as is surely the case at Ivy Plus schools, which receive many applications). Removing preferences for athletes has an effect on the share of enrolled students who come from the bottom 60% of the income distribution of a similar magnitude as removing legacy preferences.

- We searched for a random subset of smaller institutions that had lower Barron’s selectivity ratings and found very few posted CDS’s. Since these institutions do not enroll many students, how they are classified will not influence the results much but there are many such institutions, so we did not search further.

- We used a combination of automated and manual searches to find and download the CDS files. In some cases, the CDS was not a PDF or other format that could be downloaded; in those cases, we entered the relevant data directly from the website.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).