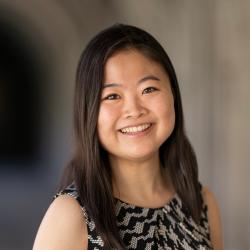

The Regional Inclusive Growth Network (RIGN) is a collaborative learning and action network designed to catalyze regional, cross-sector action to advance business norms and practices that unlock more racially inclusive growth. RIGN is made up of leaders working in eight economic development organizations, chambers of commerce, and community-facing organizations from seven small and midsized cities (SMCs); these lead organizations and their partner organizations comprise local coalitions that aim to work with and through the regional business community, with an added focus on corporate leadership, to advance effective, scaled, sustainable, and racially inclusive economic growth strategies (see map 1).1

This brief synthesizes the evidence base and motivating hypothesis for RIGN, summarized in three main findings:

- First, SMCs, which have lagged the innovation and growth of large metropolitan economies in recent decades, are now ground zero for realizing the promise of inclusive economic growth in America. But key constraints—including smaller talent pools and asset bases, plus the legacies of structural racism—stifle these regions’ potential.

- Second, in the face of changing business norms and evolving headwinds facing equity and inclusion, civic leaders in SMCs have a new window of opportunity to engage the private sector as key drivers of racially inclusive economic growth.

- Third, with new capabilities and a relentless focus on the most effective practices for shifting outcomes, civic leaders in SMCs can seize this opportunity to spur and focus business action to support—not supplant—the priorities of the communities most impacted by structural racism.

In the coming months, we will be releasing further research and insights that explore how these issues are playing out on the ground in SMCs across the country (see map 1).

- SMCs, which have lagged the innovation and growth of large metro economies in recent decades, are now ground zero for realizing the promise of inclusive economic growth in America. But key constraints—including smaller talent pools and asset bases, plus legacies of structural racism—stifle these regions’ potential.

Home to one in four Americans, SMCs and their surrounding metropolitan areas are a nationally critical locus for catalyzing inclusive economic growth—economic progress that generates employment opportunities, higher incomes, and wealth building for all, regardless of race or zip code. These urban regions have lagged the innovation-led economic growth dominated by large metro regions, in a “winner-take-most” pattern, in recent decades.

Defined as central cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000, SMCs often have strong existing infrastructure, diverse populations, and relatively affordable costs of living that present unique opportunities to harness untapped potential across the region’s residents, employers, and the overall economy. Yet, over the last decade, only three of the nation’s 85 midsized metro areas registered positive progress on each of the Brookings Metro Monitor’s indicators of growth; prosperity; and economic, racial, and geographic inclusion.

While similar challenges also affect many large cities (and their surrounding suburbs) across the country, SMCs often have fewer resources than larger cities to respond to these issues. Economic development experts at the New Growth Innovation Network have identified three ways in which smaller populations—which fundamentally characterize SMCs—uniquely constrain inclusive growth: “a smaller population . . . translates to smaller market capture for companies, smaller pools of talented workers to drive productivity, and smaller public budgets for strategic investments.” For related reasons, SMCs generally have fewer large, well-resourced institutions that can devote sizeable capabilities and investments to achieving racially inclusive economic growth.

Challenges stifling growth in SMCs will continue compounding unless leaders redesign systems with racial equity in mind, recognizing how—and how much—inclusion bolsters growth.

While a full review of the relevant evidence on structural racism and its economic ramifications is beyond the scope of this brief, it is important to begin with a clear understanding of how SMCs continue to be shaped by the impacts of exclusionary policies and practices.

First, across neighborhoods, due to a long history of racially discriminatory policies and practices, people in different neighborhoods—even within the same local economy—often experience vastly different levels of access to opportunity. Housing offers a foundational example. Federal programs related to the New Deal provided financial assistance for home purchases—but exclusively for white Americans. Meanwhile, local governments and banks practiced redlining, designating minority neighborhoods as too risky for investment. Together, redlining and other racially discriminatory policies shut out Black residents and other people of color from opportunities to purchase homes; build wealth; and, in turn, invest in their education, businesses, and communities. Today, racial disparities in homeownership—attributable to the ongoing devaluation of communities of color by, for example, real estate appraisers—continue to stifle wealth building, with effects that are more pronounced in smaller cities. According to the New York University Furman Center, “the homeownership gap between white and Black households is 7.6 percentage points greater in small cities compared to large cities.” And new threats loom as well. Growing property losses tied to the changing climate, for example, lead home insurers to raise rates and, in some states, withdraw coverage; communities of color and low-income communities are disproportionately at risk of facing greater losses and higher costs.

Residential segregation also has a range of significant downstream consequences, defining what has come to be known as an unequal “geography of opportunity.” Where one lives shapes where one can send one’s children to school, shop for food, and access health care. Thus, disparities in homeownership are compounded by exclusionary school admissions policies, persistent food deserts, unequal access to high-quality health care, and unequal burdens of pollution, all of which disproportionately harm low-income people and people of color. Residential segregation can also stifle opportunities for upward mobility, keeping social networks highly stratified by race and reinforcing neighborhood-level disparities. The interwoven nature of these inequities, however, suggests that investing in historically devalued neighborhoods and, crucially, connecting them in durable ways to the drivers of regional growth—could have win-win multiplier effects, benefiting those neighborhoods and the broader regional economy.

Second, across the workforce, the public policies outlined above helped create a structurally unequal economic playing field on which Black and Hispanic populations are now asked to compete. Owing to these upstream challenges—as well as outright hiring discrimination—racial disparities are still prevalent across the U.S. labor market. Black and Hispanic workers are highly concentrated in frontline jobs, which tend to pay less and offer fewer opportunities for career advancement. Even within the same occupations, Black and Hispanic workers are paid less than their white counterparts. A McKinsey analysis has estimated that Black-white wage disparities result in a total annual income gap of $220 billion, with close to half (44%) of that amount attributable to pay gaps within the same occupation. This suggests that racial gaps in income do not simply reflect disparities in representation (who works in particular occupations), but rather ongoing discrimination and other inequities in setting wages and salaries for workers of color compared to white counterparts. Similarly, Hispanic workers “are collectively underpaid by $288 billion a year” and receive fewer workplace benefits, when one controls for work experience and other factors. While income inequality is often higher in very large cities than in SMCs, researchers at New York University found that median income gaps between white workers and Black and Hispanic workers increased significantly in SMCs between 2000 and 2017.

These disparities compound in higher attrition rates for Black and Hispanic workers along the corporate ladder. Importantly, the attrition occurs at particularly high rates at the first step from entry-level to junior management positions—the critical step that can signal an individual’s skills and potential and that can unlock further opportunities. Researchers at the Burning Glass Institute and Harvard Business School demonstrated just how important business practices are to worker outcomes. They found that companies within the same industry vary in their promotion, pay, and retention, with significant implications for worker mobility and racial equity. Thus, addressing workplace dynamics and ensuring equal opportunities for advancement could significantly bolster economic mobility and maximize growth across the workforce. Doing so could also reduce the costs of doing business and improve worker productivity, as leading business researchers have shown.

Third, across the business ecosystem, it is well–documented that Black and Hispanic Americans are underrepresented among business owners overall, and even more so in higher-margin sectors; this pattern reflects disparities in access to wealth, capital, and social networks, which in turn are traceable to slavery, redlining, and other exclusionary policies. These gaps in business ownership are especially pronounced among the owners of employer firms with paid employees, most of all in the nation’s growth industries, such as clean energy and information technology. According to Brookings Institution research, “in 2020, Black people represented 14.2% of [the U.S. population] but only 2.4% of all employer-firm owners, while Hispanic people “represented 18.7% of the population and [only] 6.5% of employer-firm owners.” Importantly, as Gallup’s research has shown, these disparities do not reflect racial differences in inherent entrepreneurial interests; rather, they reflect structural barriers to entrepreneurship, including discriminatory lending and unequal access to capital networks. After they are founded, minority-owned firms continue to face unique barriers including financing challenges (even after controlling for credit scores), less access to mentorship and business networks, and structural racism operating through consumer perceptions and engagement.

Unsurprisingly, these disparities in business ownership can be more pronounced in smaller cities, as local governments in SMCs are less likely to have adequate resources to invest in fostering equitable business ownership and growth. Indeed, recent Brookings analyses show that, of the top ten metro areas with the highest rates of Black-owned employer businesses (relative to the size of their Black populations), only two are SMCs.

Nevertheless, growing minority-owned firms presents a critical opportunity, as they have been shown to increase employment rates in communities of color. Research has found, for example, that Black-owned employer firms hire Black people at higher rates than white-owned firms, partly because they receive applications from Black candidates at higher rates. Also, focusing on growth-driven opportunity, for example in changing industries, has the potential to mitigate zero-sum or scarcity thinking—the sense of carving up a fixed and limited pie of business opportunity. This may be especially important in SMC regions that have felt overlooked, and disconnected from much innovation and growth, for decades now—and yet these regions are beginning to attract above-average shares of new investment and newcomers.

There are clear, measurable, and growing economic and societal benefits to combatting racism.

As a large body of research attests, when given equitable access to opportunity, all people can thrive, unlocking the full potential of the nation’s economies. For example, economists at the University of Chicago and Stanford University have estimated that reducing barriers to women and Black men—by extending education, changing social norms, and reducing discrimination—has accounted for about one-fifth of the nation’s per-person GDP growth since 1960, along with significant growth in worker productivity overall. Another study, conducted by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, found that, at the local level, regions that offer greater equality of opportunity for low-income people demonstrate higher aggregate economic growth since they activate talent and productivity across a broader swath of their population.

The benefits of realizing the full potential of a racially inclusive economy are significant. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimated that closing racial disparities in earnings and education could have generated over $25 trillion in additional value for the U.S. economy over the past three decades. And this impact will only grow given the large and steady demographic transition affecting the U.S.—far more dramatically than other advanced economies. As just one indicator, according to the Brookings Institution’s William Frey, all net working-age population growth in the country over the past decade “in post-baby-boomer generations” was supplied by workers of color.

Acknowledging that economic growth is a widely shared priority among a wide range of SMC stakeholders, including private sector leaders and their civic partners, this section argues that combatting racism can unlock new economic value that generates a stronger, more inclusive form of growth. Fortunately, as discussed below, SMC leaders have a critical opportunity to activate, engage, and mobilize regional partners and assets across the private sector—gathering and also focusing collective commitments, capacities, and investments to drive systemic change.

- In the face of changing business norms and evolving headwinds to inclusion, civic leaders in SMCs have a window of opportunity to engage the private sector, including corporations, as a key driver of racially inclusive economic growth.

In the past few years, corporate America’s approach to racial equity has evolved, but businesses need to do more to deliver tangible results.

The evidence laid out above is not particularly new. While this report primarily cites the latest research, for years, businesses have been presented with regional and national evidence of the significant economic costs of racial segregation and exclusion and, somewhat more recently, the detailed business case for equity and inclusion. However, the private sector generally continued to operate, strategize, and invest in business as usual—until the summer of 2020, when businesses (and other institutions) began making major commitments to racial equity in response to critical catalysts including the Black Lives Matter movement; the mass protests of 2020 in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and police killings of other Black people; and broader campaigns for criminal justice reform, climate action, and health care and economic equity.

Many businesses have since made public commitments to combat racial injustice and support communities of color. In 2020, the nation’s 1,000 largest companies pledged $66 billion to racial equity initiatives, and that number has grown to $340 billion as of last October, according to McKinsey analysis. Norms around disclosures and reporting are changing as well. JUST Capital finds that 91% of the corporations it tracks now publicly disclose workforce diversity statistics (up from 86% in 2021), and 95% disclose their board diversity numbers (up from 84%), with records of emerging efforts on supplier diversity (42% disclose figures) and investments in local public schools (14% disclose figures), among others.

Yet some observers question whether these commitments have delivered. Making public statements of such a commitment is easier and faster than delivering meaningful results. Even of the financial investments promised, the commitments are not necessarily widespread across all large companies, let alone the vast pool of small and midsized companies. Of the $340 billion in racial equity commitments as of 2021, over 90% came from just 16 financial institutions, mostly in the form of lending targets, rather than pledges to, say, contract with a much more racially diverse pool of business owners (directly “awarding” wealth,) as leading procurement and business development experts have proposed.

Meanwhile, increased partisan polarization—specifically attacks on “woke capitalism” in political speeches and lawmaking—and unfavorable court decisions have changed the environment in which businesses operate. Some regional corporate and civic leaders have begun walking back commitments and the use of language explicit about racial equity, and these shifts in climate have fueled challenges to racial equity efforts more generally.

Despite the headwinds, a large majority of the American public remains committed to calling for businesses to do more to advance racial inclusion. Based on 2023 polling by JUST Capital, 91% of the public “agree that it is important for companies to promote an economy that serves all Americans”; and large majorities (79% of overall respondents and 88% of Black respondents) specifically believe it is “important to advance diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging in the workplace.” For the public, moreover, these steps must go beyond statements: currently fewer than four in 10 Americans believe that companies are doing well at building an economy that works for all Americans, and 52% think companies “are heading in the wrong direction”—a figure that is tied for the highest rate of disapproval since JUST Capital began its tracking in 2016. Clearly, most Americans are still looking to businesses to take more action to advance racial equity.

SMC leaders have a window of opportunity to engage the private sector anew as drivers of racially inclusive economic growth, drawing on effective and high-leverage practices, not just stated commitments.

These dynamics create an important but complicated moment for SMC civic leaders that want to engage their business communities more fully in advancing racial equity. A wide body of research finds that businesses decisions around hiring, retention and advancement, and procurement as well as public policy advocacy all have downstream impacts on economic outcomes. Encouraging businesses to move beyond a philanthropic mindset to consider how core decisions about business practices could advance society-wide equity and bottom-line business success was the central argument of the business case for equity, which has been developed over the past decade by organizations such as FSG, PolicyLink, B Lab, the Good Jobs Institute, the U.S. Impact Investing Alliance, and JUST Capital.

Thus, as employers—and also as key investors and civic leaders—private sector leaders can play an important role in improving the lives of their workers and their families and the strength and resilience of broader regional economies. In a 2021 Brookings report, Amy Liu and Reniya Dinkins recommended that business leaders pursue business practice reform as part of regional, cross-sector coalitions to maximize their collective impact: “When CEOs work in concert with other executives in their home markets and in partnership with public schools, community colleges, local governments, philanthropy, transportation providers, and others, they can exert even greater influence on systemic solutions that meet the needs of families, workers, and employers in achieving a stronger economy and society.” A diverse set of organizations—including McKinsey (a strategy consulting firm advising many of the world’s top companies) and PolicyLink (a respected nonprofit advocacy and technical assistance group)—have similarly called out the critical importance of regional, cross-sector coalitions, and today—especially in SMCs, for reasons laid out above—this collective regional action is more critical than ever.

Local, intentional, and collaborative efforts by civic leaders can help businesses advance racially inclusive growth in smaller cities and regions, not just the largest corporate hubs. Prior research shows how local civic conditions—including formal rules, policies, and regulations as well as informal norms and leadership networks—influence inclusive growth because they effectively create the local rules of the road that govern economic behavior. These rules affect markets directly by addressing the following questions: What is an acceptable, family-sustaining wage? How can talent be better matched with career pathways that offer real mobility for all? How broad-based, sustained, and effective are local supplier diversity initiatives? These rules also affect markets indirectly through their influence on politics and policy. These conditions matter in helping regions overcome external economic and technological shocks as well. Chris Benner and Manuel Pastor explore these dynamics in a diverse set of regions in their book Equity, Growth, and Community, concluding that cross-sector dialogues can help regions navigate challenges of inequality. Critically, Benner and Pastor found that how business engaged in coalitions helped determine whether they were able to genuinely serve and empower historically excluded communities.

In sum, business practices can be key drivers of racially inclusive economic growth, and civic leaders in SMCs can play a key role in advancing inclusive growth by influencing businesses’ decision-making, strategically convening key partners to support private sector action, and helping align cross-sector coalitions on regional strategies. But there is a gap between the potential of these strategies and the impact to date. The path to change can be slow and uneven, as one SMC leader told us: “While we have made some slow progress, the inability to drive sweeping change has resulted in some questioning whether this community—and especially its corporate leadership—really cares about these economic disparities.”2

- With new capabilities, civic leaders in SMCs can seize the opportunity to spur business action to support—not supplant—the priorities of the communities most impacted by structural racism.

In this moment, leaders in SMCs must be prepared to weather several overlapping challenges to advancing racially inclusive growth. On the civic front, as suggested above, the underdelivery on racial equity initiatives over the past several years has led to frustration, disillusionment, and doubts about private- and public-sector entities’ abilities to make tangible, lasting change. On the political front, partisan conflict means that business leaders, at least in some states, have become more reluctant to publicly take action to advance racial equity and inclusion—the so-called chilling effect of politicizing that pursuit. On the economic front, regional leaders must balance a number of competing priorities, including complex objectives that may appear more time-sensitive—even though, in reality, these imminent priorities may offer greater opportunities to innovate more equitable approaches—such as advancing the clean energy transition and adapting economies to emerging technologies like generative artificial intelligence.

This confluence of civic, political, and economic challenges will test civic leaders’ abilities to change narratives, forge partnerships, and take concrete actions that deliver credible results. Even strong arguments by experienced local leaders are insufficient for driving meaningful change that brings tangible benefits to people and communities in regions across the country. Beyond motivation and insight, civic leaders need to engineer—to actively build and learn by doing—for more racially inclusive economic growth.

Introducing system hubs: A new generation of civic actors that can enable inclusive growth

It is in this context that Brookings Metro launched RIGN to help strengthen the civic capabilities required for catalyzing cross-sector action for racially inclusive growth. The intermediary institutions in the network include economic development organizations, chambers of commerce, nonprofit and community-based organizations, and civic leadership groups. While there are notable differences across these institution types, they share several core attributes:

- Access to business leaders: these institutions have unique access to and credibility with business leaders;

- Civic convening power: these institutions often convene private sector leaders with leaders from the public, philanthropic, and nonprofit sectors to deliberate and discuss critical civic issues;

- A strategic economic planning role: these institutions are often responsible for shepherding multiorganizational coalitions to develop and execute long-term economic strategies; and

- Influence over investment priorities: these institutions often help shape how business and philanthropic investors support and learn from key economic investments in their regions.

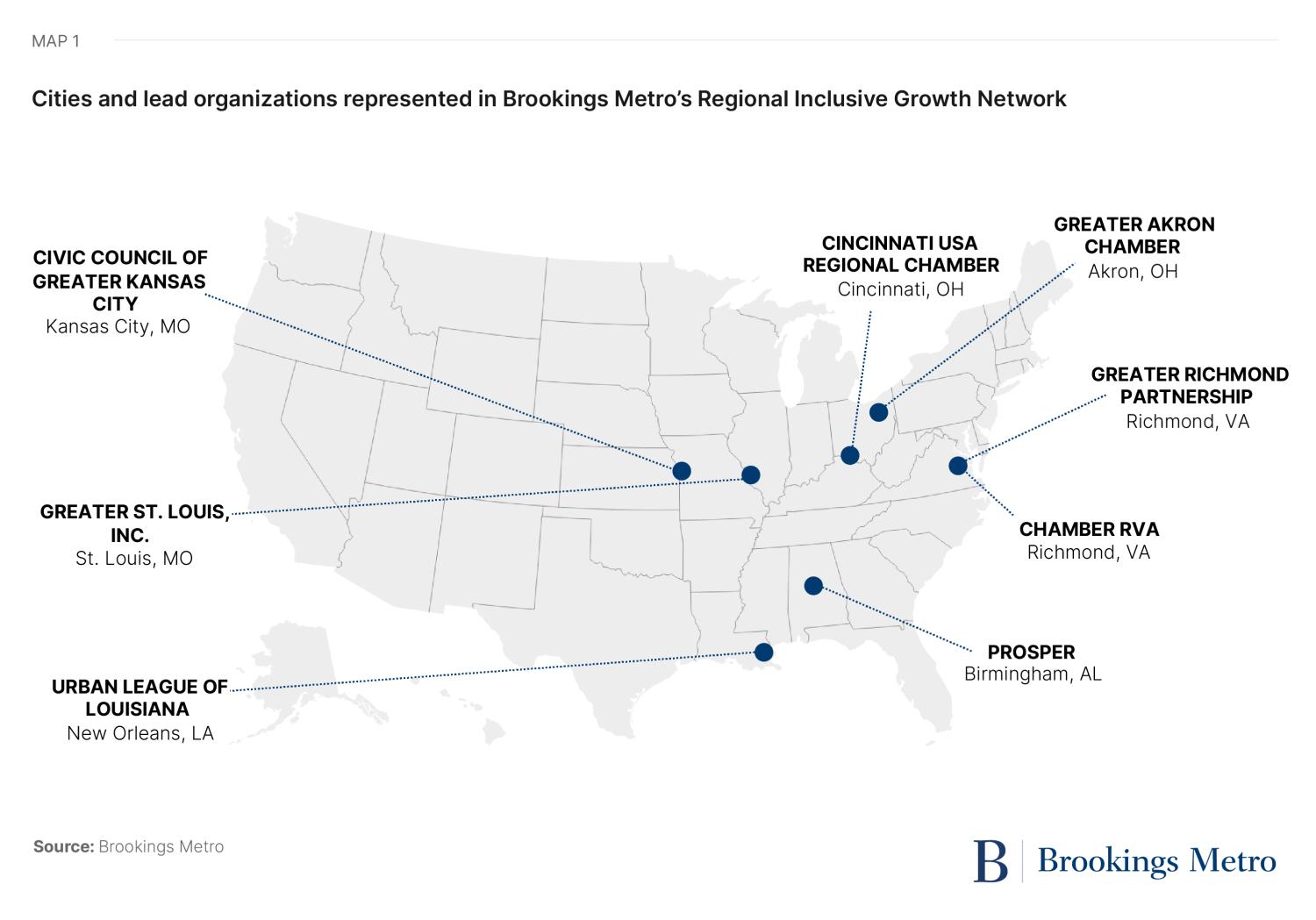

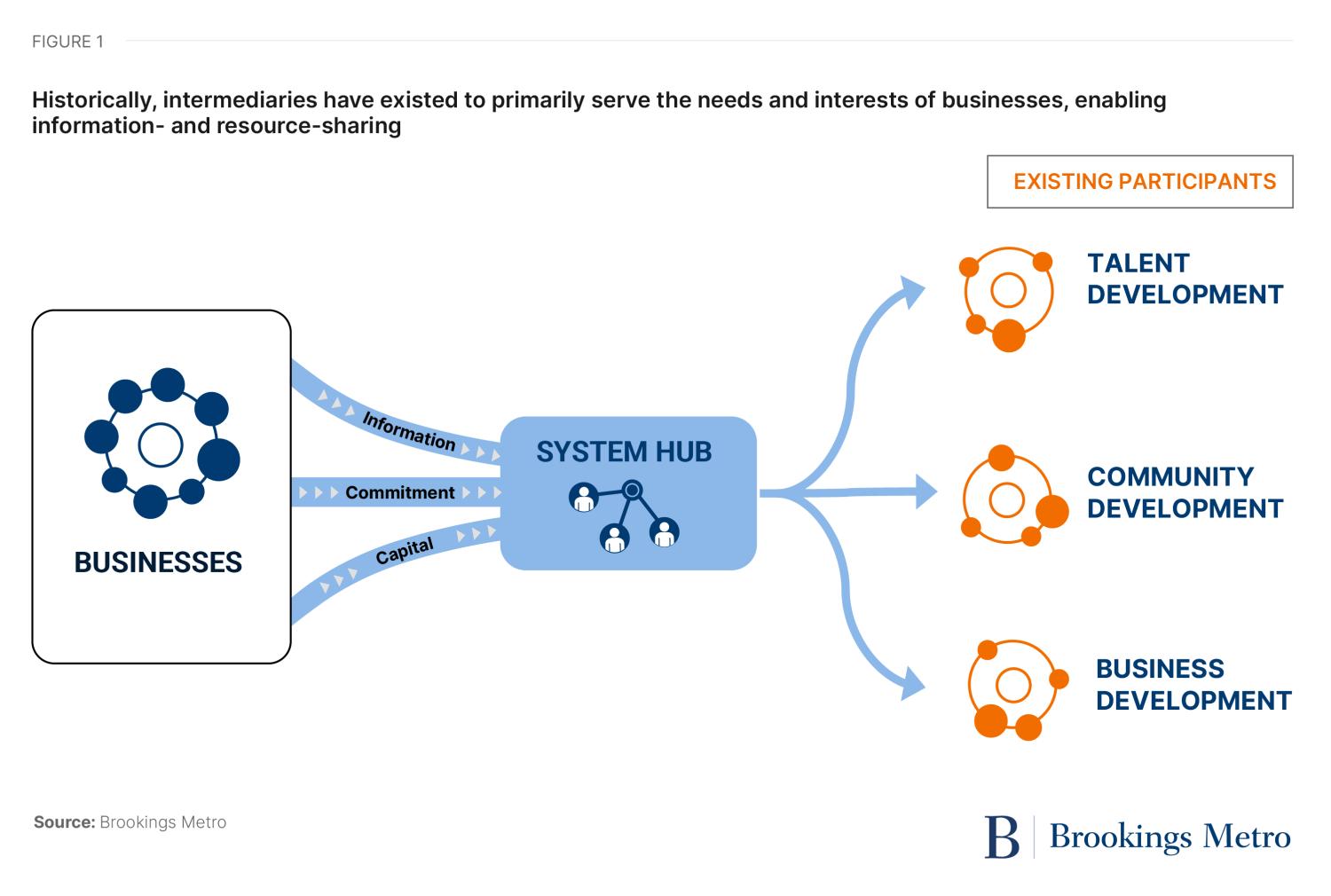

Given these key attributes, intermediaries like those in the network have the unique potential to generate commitments, gather information, and source capital from businesses to invest in more racially inclusive economic growth. But to do so, many must evolve their role: Historically, many of these intermediaries have existed to primarily serve the needs and interests of businesses, enabling the sharing of information and resources and advocating for the priorities of the business community broadly (see figure 1). But now, they must shift from simply being well-connected with business leaders to being true connectors between businesses and the surrounding systems that shape racially inclusive growth—including community development, workforce development, and business development—in what we call a “system hub” role (see figure 2). As system hubs, intermediaries play bidirectional roles, not only serving businesses but also shaping their behavior, challenging them to shift their own policies and practices—and enabling businesses to more consistently push each other—to better advance racially inclusive growth.

One key caveat applies: aspiring to be a system hub does not mean that these organizations occupy a central or lead role in directing how these external systems (such as workforce development) function. In fact, notwithstanding the valuable attributes of system hubs laid out above, these organizations cannot do it all: With the notable exception of the community-facing organizations in the network, these institutions rarely bring direct access to, representation from, or deep credibility with historically excluded communities. They also do not typically deliver direct services in key systems like business development, talent development, and community development. These gaps, then, illuminate key opportunities for system hubs to strategically convene cross-sector partnerships that leverage the strengths of existing organizations and extend their reach to serve shared regional goals of inclusive economic growth.

These linkages between businesses and external systems are critical. If employers want to source and invest in overlooked talent, they will not only have to change their own policies and practices but will also need stronger, more outcome-driven partnerships with community colleges and other workforce development partners. If businesses want to reap the full benefits of adopting more inclusive procurement strategies, they will need stronger partnerships with business development organizations. If they want to maximize their returns on investment in more inclusive places for their employees to work, they will need stronger partnerships with community development organizations. Many of these system partners are already embedded in and attuned to the needs and experiences of the communities served by those systems, and they have expertise in delivering those services. Thus, the role of system hubs is not to recreate those systems; rather, system hubs can play a vital role in strategically convening employers with these system partners—many of which have historically been sidelined—to improve how employers interact with, invest in, and ultimately strengthen those systems.

Acting as a system hub is not easy, especially given uneven corporate leadership, underinvested systems for expanding economic opportunity, and legacies of distrust or limited expectations that things can change. To consider this new role, we outline four core capabilities that system hubs can develop to better advance racially inclusive growth:

- Strengthen collaborative capacity: Regularly engage and/or organize the full range of actors—both top decisionmakers from employers as well as a diverse set of community partners—to build a shared and actionable understanding of priorities, strategies, and available resources. Part of the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber, the Workforce Innovation Center was founded to connect more employers directly to the many workforce and community support initiatives that exist to mitigate barriers to employment.

- Create a call to action: Set clearly defined, ambitious, long-term goals focused on racially inclusive growth, with mechanisms to measure and evaluate progress and periodically revise strategies as well as clearly articulated roles and responsibilities for businesses. For example, the Urban League of Louisiana catalyzed a clear call to action through its SEE CHANGE Collective, a data-driven, community-oriented, and outcomes-focused initiative committed to identifying policy and practices to close the racial wealth gap in the Greater New Orleans region.

- Identify system gaps: Have a strong understanding of how local systems work and how they should work, with all actors knowing their exact role (especially employers), how they relate to other organizations, and where gaps need to be filled. In Birmingham, Alabama, Prosper, a civic intermediary, and leaders at Regions Bank identified local gaps in capital access, tailored support for Black-owned businesses, and subsequently launched the Birmingham Black-Owned Business Initiative to help more Black-owned business thrive.

- Channel capital to implementers and effective approaches: Have a strong understanding of what is working and what is not working and why, and then help direct government, philanthropic, and business funding to the highest-impact areas and implementers. Greater St. Louis Inc., for example, helped channel $25 million from the Economic Development Administration toward an inclusive advanced manufacturing cluster initiative, providing funding to a coalition of more than a dozen implementing organizations already having an impact across the region.

The work ahead

This brief has argued that there are both moral and market imperatives—but also headwinds posing all-too-familiar challenges—for the private sector to invest in racially inclusive economic growth; translating corporate commitments in particular—which can be especially important drivers of change—into tangible, on-the-ground impact requires a coordinated, regional, cross-sector approach.

Successful activation of regional inclusive growth initiatives would provide a meaningful shift away from the status quo, toward more equitable and inclusive economies. This is doubly important, and the stakes extraordinarily high, in the small to midsized economic regions of the nation, as they have lagged the big “superstar” metro economies on innovation and growth. Grounded in earlier research and the lived experience of many practitioners and community voices, the strategies and institutional capabilities discussed above are intended to help empower civic leaders across SMCs to catalyze private sector action, ultimately to advance racially inclusive economic growth in ways that serve businesses’ own economic priorities and deliver significant gains to their communities.

RIGN is now putting these concepts, and the working hypotheses outlined here, into action through in-depth work with civic leaders in seven SMCs. These leaders aim to channel their resources toward scaled, sustainable, and inclusive economic development strategies. Together, these actors and Brookings Metro will explore a range of key questions:

- What data, tools, and frameworks can help catalyze systemic change toward inclusive business practices? How can regional civic leaders apply evidence-based tools and insights to drive shifts in business commitments, investments, policies, and practices?

- What capabilities enable institutions to mobilize private sector action toward racially inclusive economic growth? How can these institutions better strengthen collaboration, create a shared call to action, identify gaps in existing systems, and channel capital to key implementers?

- What narratives are most compelling and effective for promoting racially inclusive growth, particularly in the face of political and legal headwinds to racial equity efforts? How are regional civic leaders navigating these headwinds on the ground?

- How can the diverse range of actors in each region combine support for business progress with meaningful mechanisms that promote accountability for results? Historically, support has often come in the form of insights, technical assistance, and perhaps positive public recognition. Accountability, on the other hand, typically counts on sustained and constructive pressure for change, operating both inside and outside of businesses. But healthy pressure can matter for improving other organizations as well: agencies in local and state governments, higher education, community-based advocates and service providers, and more.

Over the next year, Brookings Metro—in partnership with civic leaders across seven SMCs—will gather local insights, document challenges and bottlenecks as well as successes and opportunities, and analyze what it all means for regional efforts across the country to advance racial equity and inclusive growth.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) made this project possible, and we are particularly grateful to James Hardy and Chloé Nuñez at RWJF for their ongoing support and guidance. In addition, we’d like to thank the following individuals for helpful feedback on an earlier draft: Alan Berube, Ryan Donahue, Tracy Hadden Loh, Hanna Love, and M. Yasmina McCarty. All remaining errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors. We’re grateful to members of the Regional Inclusive Growth Network, who helped inspire and sharpen this brief. Finally, we’d like to thank Tawanna Black and Andrea Ferstan of the Center for Economic Inclusion for their participation in the design and launch of the Regional Inclusive Growth Network.

-

Footnotes

- The seven SMCs participating in RIGN include Akron, Ohio; Birmingham, Alabama; Cincinnati, Ohio; Kansas City, Missouri; New Orleans, Louisiana; Richmond, Virginia; and St. Louis, Missouri.

- This information comes from documents submitted to Brookings Metro by a leader at a regional chamber of commerce, July 2023.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).