The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Molly Curtiss Wyss and Johannes Linn for their input.

Education systems have been quick to teach about innovation and painfully slow to innovate in the way we teach. Our research suggests that the problem does not reflect a lack of promising new practices but rather a failure to scale most of those improvements. Fortunately, that has begun in recent years to change; however, we believe much more can, and must, be done.

We have been investigating for several years the role of external funders in supporting enhanced education outcomes at scale. We have done so in two ways: through a 4000-member community of practice focused on scaling development outcomes, and through the Millions Learning project. This commentary summarizes some of the insights from this work related to the role of funders in scaling education interventions. It discusses patterns observed among education funders in their efforts to support the mainstreaming, or integration, of education innovations within an existing education system and points to where further progress is needed to achieve large-scale and lasting improvements in children’s learning. In this piece, “education funders” refers to philanthropic donors representing foundations, innovation funders, and bilateral and multilateral donors.

Here are four observations we have made about the current state of practice related to funders’ roles:

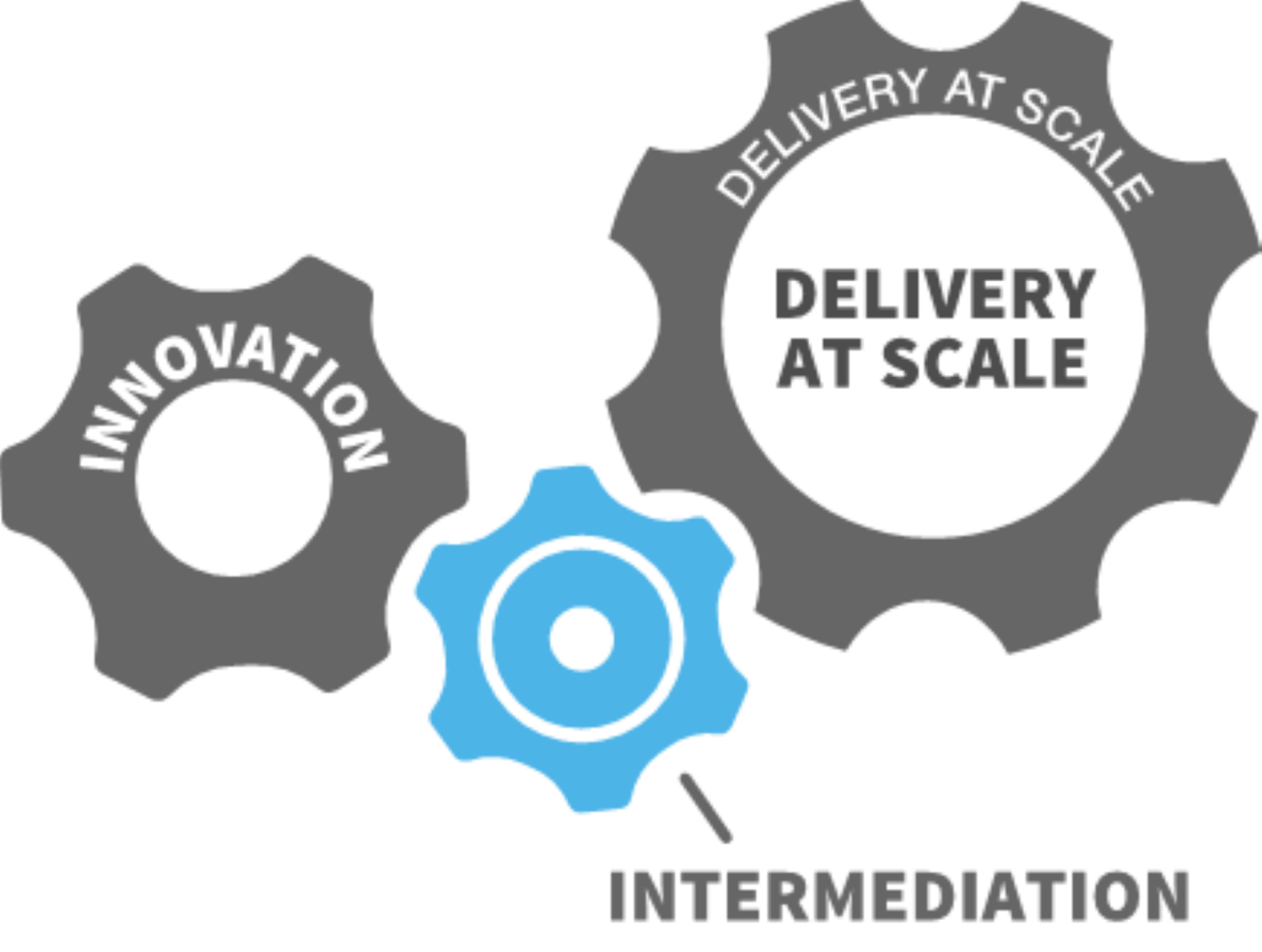

1. Intermediation—connecting smaller innovations to larger-scale delivery—is an under-resourced, yet critical area, ripe for funders’ support.

The graphic above is one way of thinking about the mainstreaming of new policies and practices within an education system. On the left-hand side, the smaller gear represents experimenting, piloting, and confirming the efficacy of education innovations. This is where NGOs and funders tend to concentrate. The right-hand side, and largest gear, is typically the government’s domain—delivering education to all children.

The challenge—and where things tend to break down—is in the middle, the blue gear depicting the “intermediation tasks” necessary for connecting innovations with large-scale delivery. These tasks include investment packaging, policy, and budget advocacy, facilitating agreement among diverse stakeholders, and project planning. In the absence of institutions that are able, motivated, and positioned to perform these tasks, the vast majority of promising innovations never transfer to the larger gear and therefore fail to address the scope of the educational challenges faced. We believe this is a place where external funders can play a particularly important role.

2. Education funders have embraced the narrative of scaling, but this hasn’t translated into widespread changes in policies and practices.

Scaling as a goal increasingly appears in funders’ strategies and plans, and some have moved beyond rhetoric to enacting operational changes in their grantmaking. In some cases, this has translated into funders giving larger tranches of more flexible funding and/or extending their funding over longer periods of time. In other instances, funders have focused beyond project implementation and more tangible outputs to strengthening field building and key organizational capacities in service of broader impact.

Where this has happened, the benefits have been clear. For example, in the case of Ahlan Simsim—a joint venture between Sesame Workshop and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) supported by the MacArthur and LEGO foundations in response to the Syrian crisis—significant increases in the numbers of communities reached and outcomes achieved didn’t happen until year four, when interventions designed with government ministries launched. Analysis by IRC’s Ahlan Simsim team indicates one of the core enablers of this was the long-term and flexible nature of the financing (see Figure 2).

However, changes in donors’ practices remain limited. Organizational inertia and existing incentives contribute to a reality where one-and-done projects lasting one to five years remain the rule, not the exception; metrics continue to focus on direct beneficiaries; partners during project planning rarely prioritize those organizations that will be responsible for implementation and delivery at scale; and government concurrence is frequently mistaken for government ownership. An additional, ironic consequence of the increased emphasis on scaling is greater pressure and perverse incentives to scale prematurely.

3. Funders have varying approaches to collaboration and partnership, which impacts how they view their role and how they approach financing.

We have witnessed a more nuanced understanding of scale and systems change and transformation emerging among the education funder community. However, we have also noted considerable differences among funders in their respective concepts of scale and scaling. These different conceptualizations have direct and profound implications on how resources are allocated and how initiatives are designed, implemented, and monitored.

Intellectually, funders understand that sustainable scaling requires a shift in how institutions function, incorporating changes in policies, procedures, and organizational culture. They also seem to appreciate that this takes time, pragmatism, political savvy, and collaboration. Nevertheless, most persist in their efforts to scale project-based interventions in their entirety rather than scaling specific components or aspects, and most maintain a focus on direct delivery rather than changes that contribute to broader systems change. This shortcoming is compounded by the fact that, in too many places, fragmentation has increased with growth in the number of funders with the unintended result that it is ever more common for funders to support multiple groups doing very similar work in the same place and pass opportunities to pool or leverage their investments, collaborate, and work through government systems. The incentives for NGOs and other innovators reflect donor policies and, therefore, similarly encourage differentiation rather than integration.

4. Much has been learned about innovative financing of the “middle stage” of scaling.

Encouragingly, the global education community is learning much more about navigating the “middle phase of scaling” after piloting and expansion but before reaching sustainable delivery at scale. This period, often referred to as the valley of death, is where many promising innovations die. It is a period typically longer and more political in the education sector than in other sectors given the dominant role of government policies and budgets and the semi-autonomous behavior of schools and teachers. Historically, this has been challenging for funders for many reasons, including short-term project cycles, changing strategies, and desires for attribution and branding. Equally challenging is the political economy of transitioning from external funding to government budgets or other sustainable sources.

But the number and range of positive examples are growing. The five case studies investigated as part of the Millions Learning Real-time Scaling Labs manifest different and successful strategies for navigating this valley of death aided, in each case, by innovative injections of flexible financing during this middle phase. For example in Jordan, a financial education program delivered across all secondary schools has been financed by a public-private partnership between the government, foundations, and a levy on the profits of commercial banks. This long-term, reliable financing was critical in driving the scaling process forward. In each case, these investments were relatively large and for longer-than-usual periods of time, and each was accompanied by technical support for developing scaling strategies from the start; resources for intermediary partners to assist with developing scaling plans, facilitating collaborative learning and documenting lessons; and flexibility to change course as needed. We have come to believe that this type of funding may well be required to navigate this middle phase of scaling, and we are optimistic that funders are beginning to absorb this reality.

The education funder community has made much progress in recent years in adopting a systematic approach to sustainable scaling. However, there is still much to learn—and much to do—if mainstreaming these approaches is to become standard practice and the “new normal.” We believe that immediate actions education funders can take include:

- Adopt internal procedures in support of sustainable scaling, including 10–15-year time frames, flexible funding, encouragement of collaborative partnerships, and adaptive learning.

- Prioritize during design and implementation the development of scaling plans that serve as “living documents” and are developed collaboratively with those who will be responsible for delivering and financing at scale.

- Acknowledge the distinction between government concurrence (i.e., a ministry allowing an NGO to implement a program in government schools) and government ownership (i.e., a ministry dedicating budget and personnel to deliver a program over time, at scale), and adopt strategies for ensuring genuine government ownership of innovations.

- Focus measurement on indirect beneficiaries and institutionalization of change, de-emphasizing direct attribution and branding of specific innovations.

- Enhance attention to, and funding for, intermediation in support of services, such as the development of scaling strategies, coalition building, investment packaging, field strengthening, documentation, and sharing of lessons learned.

At the current pace, the world will fall far short of achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring all children have access to quality education and lifelong learning by 2030. We are unlikely to close the gap by relying exclusively on quantitative expansion of current practices and on the current practices of funders without also introducing and scaling an array of impactful and cost-effective innovations and a range of new funder strategies. Evidence is accumulating that donors are beginning to acknowledge these realities, but much remains to be done to translate these lessons into practice.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or the funders acknowledged below.

The LEGO Foundation and the John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation are donors to the Brookings Institution. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in the absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Funders’ role in scaling education innovation

March 8, 2024