The European Central Bank (ECB) has in recent years intervened in government bond markets to cap yields, most obviously so in mid-2022 when it bought Italian and Spanish debt. That episode sets a tricky precedent for the ECB as uncertainty in the run-up to French elections impacts markets. In the case of Italy, ECB bond buying in June and July 2022 coincided with the post-COVID inflation scare, which pushed up yields, but also with the surprise resignation of Mario Draghi and an ensuing election that made Giorgia Meloni prime minister. If some now argue that the ECB should stay on the sidelines to remind the political extremes in France how costly fiscal profligacy can be, that risks making the ECB look like it is choosing sides. If eurozone debt markets continue to sell off, the ECB will have no choice but to intervene. The underlying difficulty is that discretionary ECB operations in eurozone bond markets are inherently political. That is why quantitative easing under President Draghi was tied to the capital key, to prevent country-specific skew in purchases that might look political. It’s worth considering a return to that baseline for the ECB.

The bond market sell-off so far

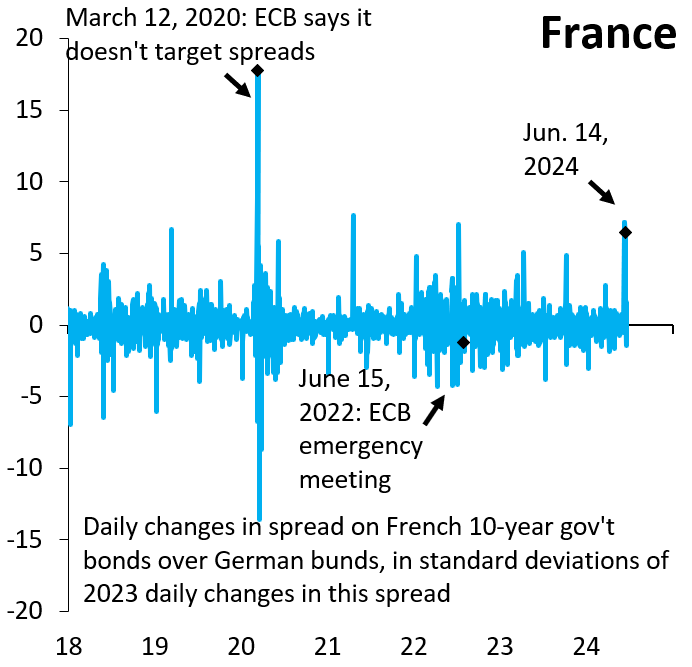

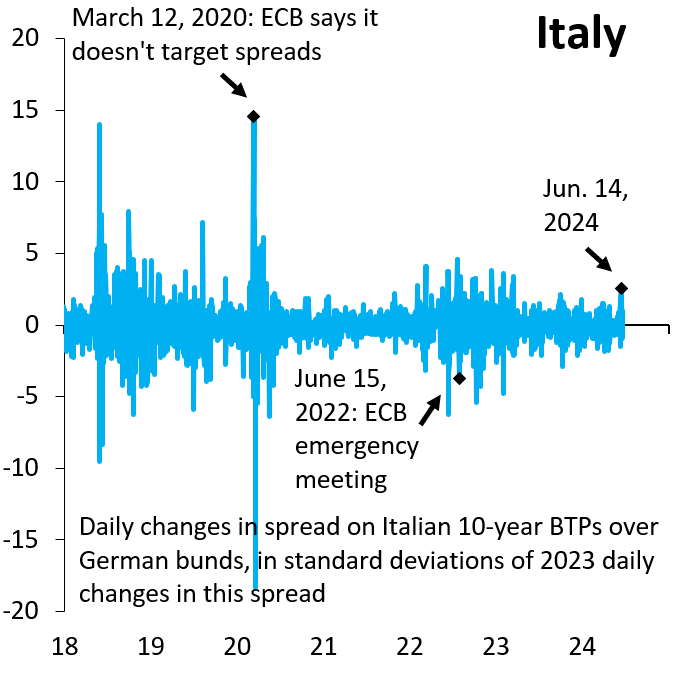

Uncertainty in the run-up to French elections caused large bond market moves last week. The spread of the 10-year French government bond yield over its German counterpart registered a six standard deviation jump on Friday, June 14 (Figure 1), one of the biggest increases since March 2020, when President Lagarde shocked markets by saying the ECB “isn’t here to close spreads.” This widening in the French spread was accompanied by signs of contagion to Italy, where the spread registered a two standard deviation jump on the same day (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Daily changes in spread on French 10-year government bonds over German bunds

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 2. Daily changes in spread on Italian 10-year government bonds over German bunds

Source: Bloomberg

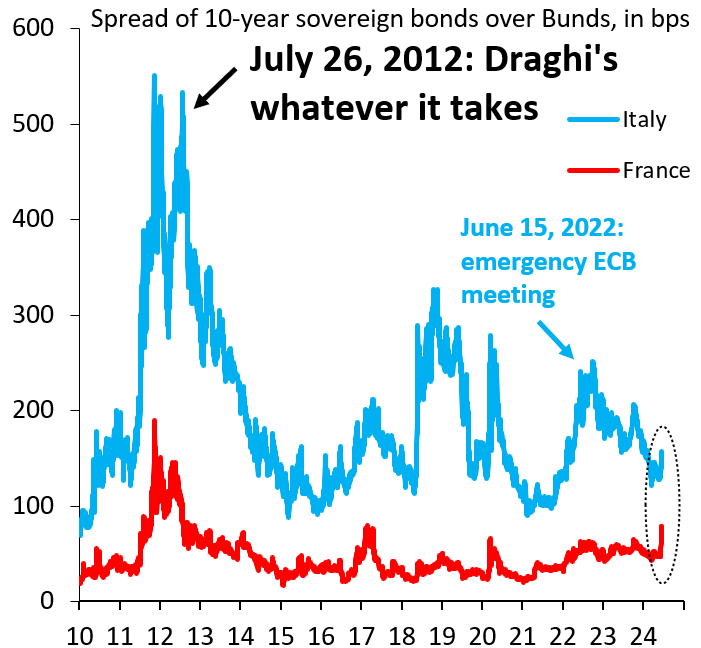

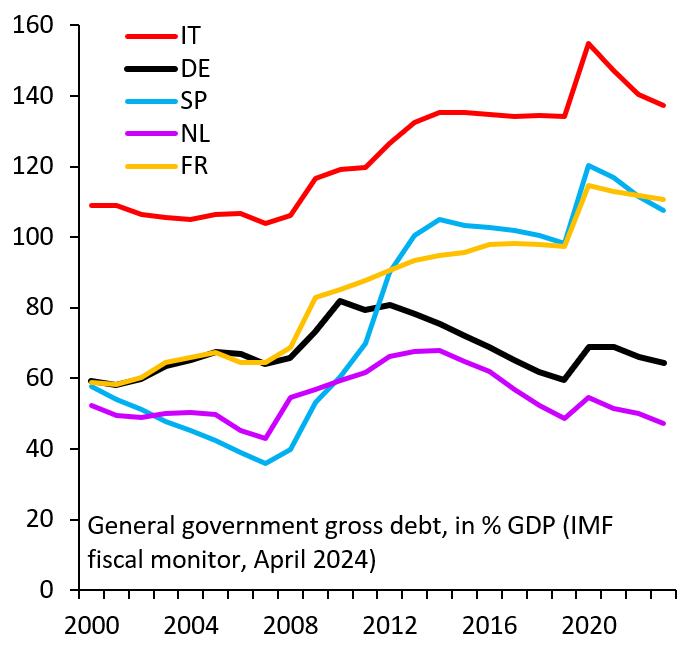

While last week’s moves are unnerving, spreads for France and Italy are extremely low by historical standards (Figure 3), so that—unless the bond market sell-off worsen materially—there really is no need for ECB intervention at this stage. That said, narrow spreads are also a source of vulnerability. Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio is 140%, substantially above that of Germany, which lies around 60%. Rising interest rates increase the risk of having lots of debt, so Italy’s spread should widen as German yields rise. That has not been the case in recent years (Figure 4), raising the risk that spreads could widen sharply if ECB policy toward the periphery changes.

Figure 3. Spread of 10-year sovereign bonds over bunds

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 4. 10-year sovereign bond yields, in %

Source: Bloomberg

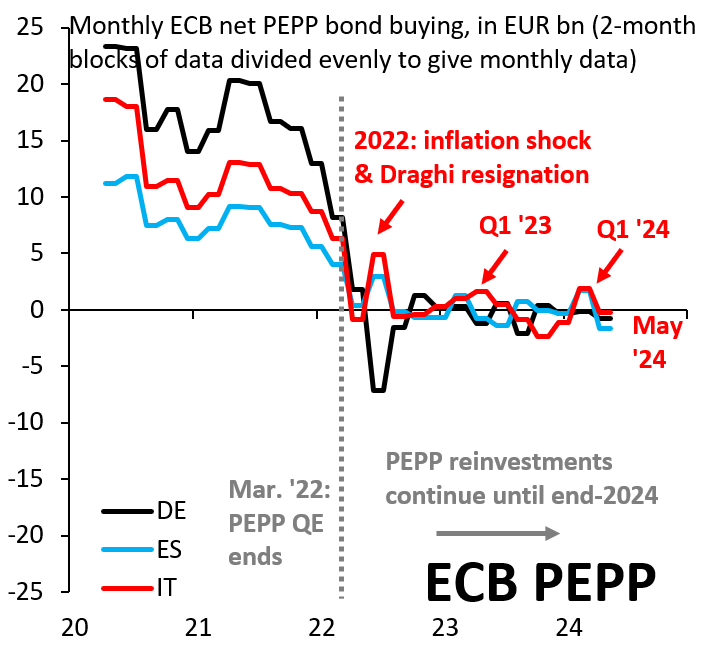

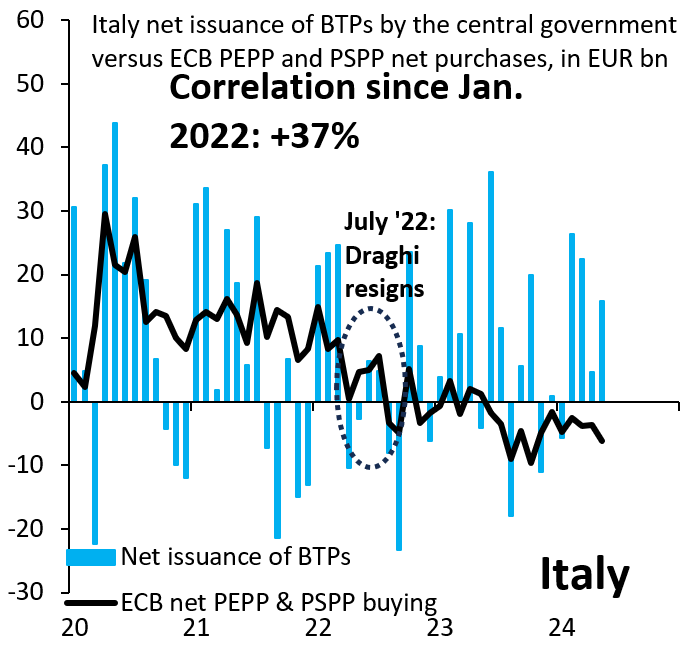

European Central Bank bond market interventions in 2022

In early 2022, the post-COVID inflation shock was peaking. Bond yields were rising everywhere and the consensus at the time was that: (i) inflation was to a material degree demand-led; and (ii) central banks were substantially behind the curve in countering this phenomenon. On June 15, 2022, the ECB surprised markets by holding an extraordinary policy meeting, which set in motion preparations for its new anti-fragmentation tool subsequently named the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). It also became clear—with a lag—that the ECB was using proceeds from primarily maturing German government bonds to buy Italian and Spanish debt (Figure 5). This buying was large enough to take Italy off the market, with ECB purchases absorbing all of Italy’s net new debt issuance (Figure 6). The ECB only publishes these data in two-month chunks, so it is impossible to say when buying was concentrated in the June and July two-month window. However, July saw Mario Draghi resign as prime minister, setting the stage for snap elections in September, which brought to power a coalition led by hard-right politician Giorgia Meloni. The parallels with recent events in France are hard to miss, which makes it unlikely that the ECB can stay on the sidelines if the current bond market sell-off worsens materially. Taking no action would be just as political as stepping in to cap spreads.

Figure 5. Monthly European Central Bank net PEPP bond buying

Source: European Central Bank

Figure 6. Italy net issuance of BTPs by the central government vs. ECB PEPP and PSPP net purchases, in EUR bn

Source: European Central Bank and Italian Ministry of Finance

Eurozone grand bargain needed

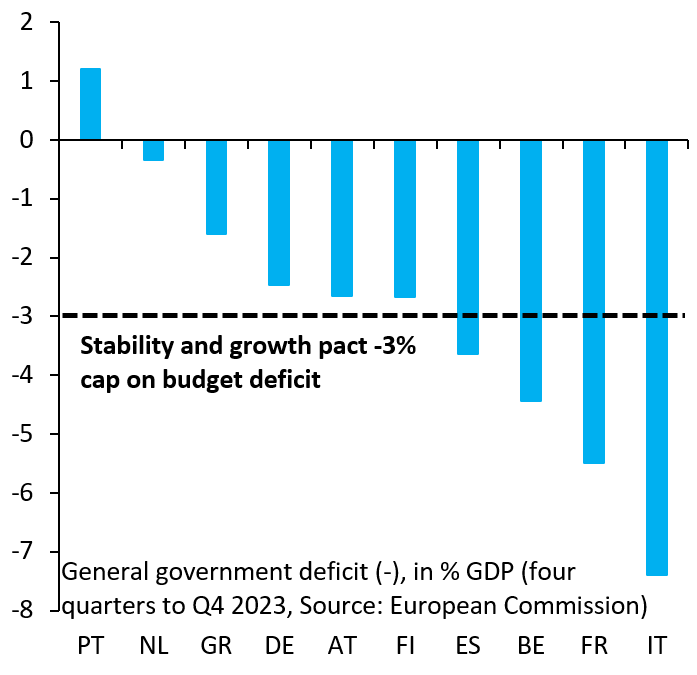

The underlying truth is that discretionary bond market interventions are inherently political. After all, if Italy’s yield had been allowed to rise in 2022, perhaps the Draghi coalition would have lasted, buoyed by market volatility and more support for a trusted pair of hands. This is why ECB quantitative easing was constrained by the capital key when it first began in 2015, to prevent discretion in policymaking that might benefit one country over another. The ECB should consider a return to that baseline. This would also go some way to incentivizing fiscal prudence among highly indebted eurozone countries (Figure 7), where it is currently Italy and France—among the most highly indebted countries—who run the widest budget deficits (Figure 8). Such a move will come with more market volatility, but the alternative is that debt reduction never comes back onto the agenda. In the big picture, the eurozone needs a grand bargain, whereby highly indebted countries use wealth taxes to bring down public debt, even as low-debt Northern countries agree to permanent fiscal transfer mechanisms. That will be the starting point for the ultimate goal, which is fiscal union.

Figure 7. General government gross debt, in % GDP

Source: International Monetary Fund

Figure 8. General government deficit, in % GDP

Source: European Commission

Commentary

French elections and the European Central Bank

June 20, 2024