The one-minute version of this case study

- For the Central Valley region, agriculture is both a lifeline and environmental risk. California’s Central Valley is a nationally significant agricultural region that supplies 25% of the United States’ fruits and nuts despite comprising only 1% of its farmland. Not surprisingly, agriculture is a key economic driver in the area, accounting for 14% of gross domestic product, 17% of jobs, and 19% of revenue in the San Joaquin Valley alone (the region’s southern half). However, growing water shortages, the quickening pace of climate risks and disasters, ongoing threats of farmworker displacement from technological innovation, and persistent patterns of racial and geographic inequity threaten the Central Valley’s position as a global leader in agricultural production.

- The Central Valley region’s core challenge—and opportunity—is building a resilient and inclusive agricultural technology cluster. By 2040, the region’s water supply could decline by 20% due to the combined impacts of climate change, threatening 900,000 acres of farmland and 50,000 jobs for the majority-Latino or Hispanic and low-income workforce. To maintain economic competitiveness and inclusive opportunity for all residents, the region must embrace agricultural technology for climate-adaptive and sustainable food production. Yet previous technological innovations in the region have cost tens of thousands of jobs, fueling tension and distrust between farmworkers and industry. Given these tensions, regional leaders recognized the need to endorse a BBBRC strategy that harnesses agricultural technology as a tool for inclusive prosperity and inclusion, rather than worker displacement and exploitation.

- The Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) is helping the region invest in a bold climate resilience and inclusion initiative. With the largest award out of all 21 BBBRC grantees—and one of the only BBBRC coalitions led by a community foundation—the Fresno-Merced Farms-Food-Future (F3) Coalition’s $65 million BBBRC strategy aims to align the often competing interests of farmworkers, environmentalists, industry, agriculture technology (ag-tech) practitioners, and different regional anchor institutions toward a bold vision to bolster the region’s resilience and competitiveness and promote a climate-adaptive food production ecosystem, all rooted in principles of equity, inclusion, and environmental sustainability.

- Advancing an inclusive cluster initiative requires intentional work to build trust and secure buy-in from workers, industry, and residents. This case study explores the design and implementation of the F3 Coalition’s ag-tech cluster strategy, including research and innovation through new university-industry-community partnerships, support for local farmers and food entrepreneurs, and the deployment of an industry-approved ag-tech certificate program across seven regional community colleges for upskilling incumbent farmworkers. It offers lessons on how economic and community development leaders can effectively build trust, overcome historical harms, and bolster inclusive and resilient economies, particularly in regions grappling with new technological innovations as well as longer-standing tensions between workers and industry.

Before reading this case study: What is the Build Back Better Regional Challenge?

This brief overview of the program provides useful context before reading this case study.

In July 2021, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) launched the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) through a Notice of Funding Opportunity that outlined a two-phase competition.1 Through its Phase 1 activities, the EDA issued an open call for concept proposals that outlined a high-level vision for a “transformational economic development strategy.” The thesis was that regions would identify an industry cluster opportunity; design “3-8 tightly aligned projects” to support that cluster; build a coalition to “integrate cluster development efforts across a diverse array of communities and stakeholders”; and ensure that these collective efforts advance equity by supporting economically disadvantaged communities.2

In Phase 1, 529 coalitions submitted high-level concept proposals that outlined a vision for the cluster, a high-level description of potential projects, and the key institutions involved in the coalition. After receiving Phase 1 concept proposals, the EDA undertook two months of review to determine which coalitions would be awarded $500,000 technical assistance grants and invited to apply for Phase 2 funding. Those resources enabled a hyper-intensive planning sprint between December 2021 and March 2022. During this period, each of the 60 finalist coalitions expanded their five-page concept proposal into an overview narrative and project proposals that outlined their approach, key assets and institutions, the portfolio of projects and their expected outcomes, and matching resources to complement the EDA grant.

Ultimately, the 60 coalitions submitted funding requests well beyond the BBBRC’s $1 billion allocation. The average Phase 2 funding request submitted to the EDA was approximately $75 million, while the average award amount available in the competition budget was approximately $50 million. Given this gap, in May 2022, all 60 applicants were offered the opportunity to prioritize funding through a budget request reduction process after applications were received. Then, an Investment Review Committee (IRC) assessed all completed applications and made recommendations. In some cases, the EDA ultimately selected a subset of component projects for funding or funded component projects at a reduced level, requiring applicants to modify projects during the award process. In September 2022, the EDA selected 21 of the 60 coalitions for implementation awards, ranging in size from $25 million to $65 million, to be spent over a five-year period.

Background

The Central Valley lies at the intersection of several distinct economic, environmental, and public health contradictions. As the “agricultural heartland” of California, the region supplies 25% of the United States’ fruits and nuts despite comprising only 1% of its farmland. Even with these agricultural resources and productive output, Central Valley residents face stark socioeconomic inequities. For instance, 55% of Central Valley residents live in a state-identified “disadvantaged” census tract, the region’s unemployment is twice the national average, and it has consistently ranked low on indicators of racial and geographic inclusion.

The cascading effects of climate change have only worsened the region’s inequities and threatened its position as a global leader in agricultural production. All five Central Valley counties (Fresno, Kings, Madera, Merced, and Tulare)—which are home to over 2 million people, 70% of whom are people of color—received failing grades from the American Lung Association for having high levels of ozone and short-term particle pollution (PM2.5). Moreover, nearly 80% of disadvantaged communities in the San Joaquin Valley are without potable water. By 2040, the average water supplies in the Central Valley could decline by 20%—threatening 900,000 acres of farmland and 50,000 jobs.

Many of the region’s socioeconomic inequities can be traced to a history of tensions between farmworkers, industry, and the United States government. In 1935, the National Labor Relations Act excluded farmworkers and domestic workers from federal labor protections, essentially entrenching economic and physical exploitation as common practice among many agricultural industry employers for the next 30 years. In the early 1940s, the Bracero Program enabled millions of Mexican men to migrate legally to work on U.S. farms, but ultimately subjected many to wage theft, abuse, and poor working conditions prior to the program’s conclusion in 1964, after which many were left undocumented and unprotected.

Two farmworkers with a rich history of organizing in the Central Valley—Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta—were instrumental in rectifying some of these harms through successfully advocating for wage increases and the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. But despite significant wins, the seeds of distrust between workers, industry, and government had been planted.

Industry-led agricultural technological innovation, in particular, has remained a lingering source of tension in the region. For example, the mechanical tomato harvester created by University of California, Davis in the mid-1950s led to the displacement of 82% of tomato growers and a loss of 32,000 farmworker jobs in just five years. Fears of similar displacement and loss have rendered many farmworkers and community-based organizations skeptical of agricultural technology, and committed to improving the livelihood of Central Valley residents first before enhancing global production through innovation.

The world of the Central Valley spins around these mega food producers. The local community groups tell us, ‘We don't care that these folks are growing enough almonds to make sure China has what they need next year because folks here in the Central Valley are starving. Who cares if we feed the world if we can't feed our own place?

A Central Valley-based regional stakeholder

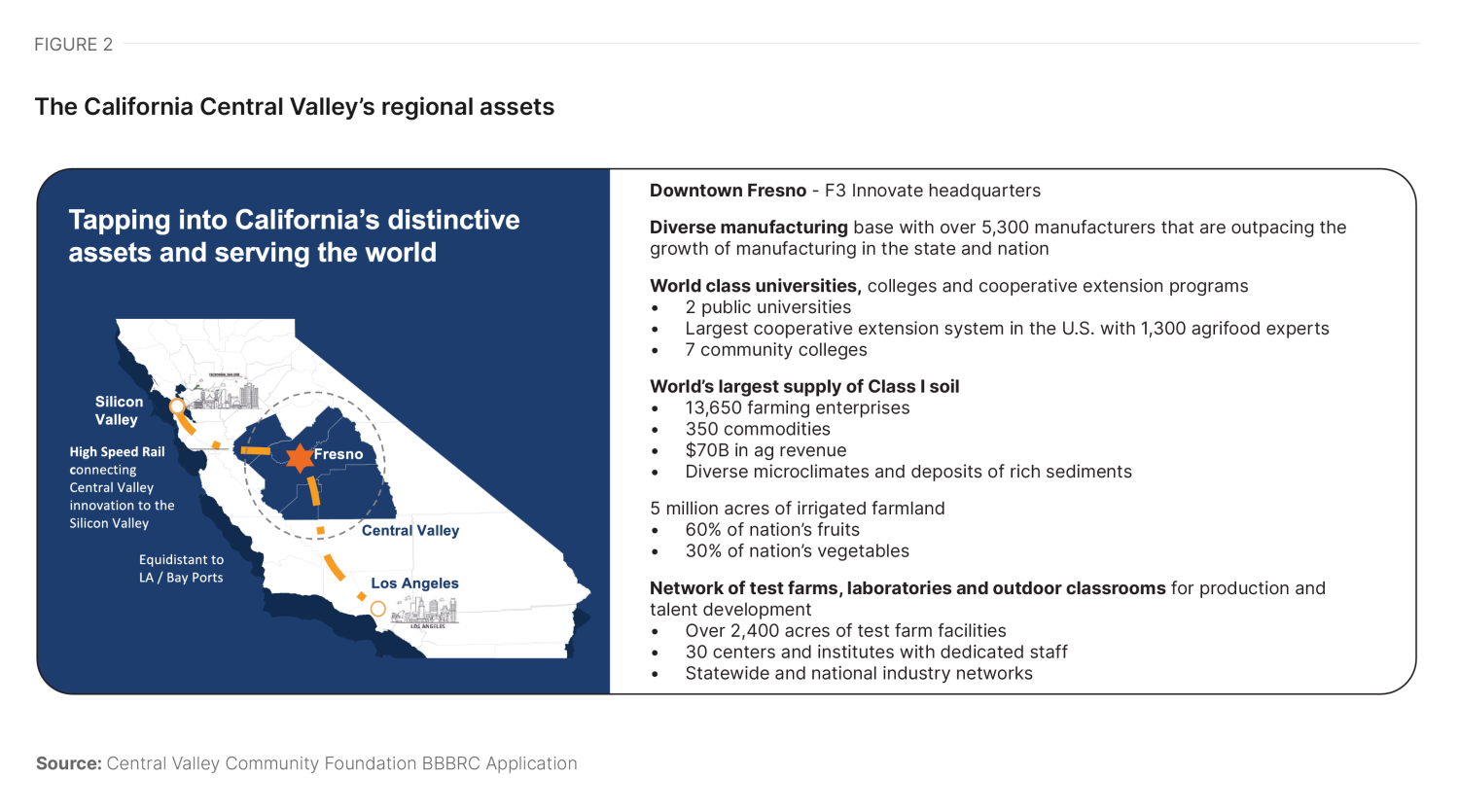

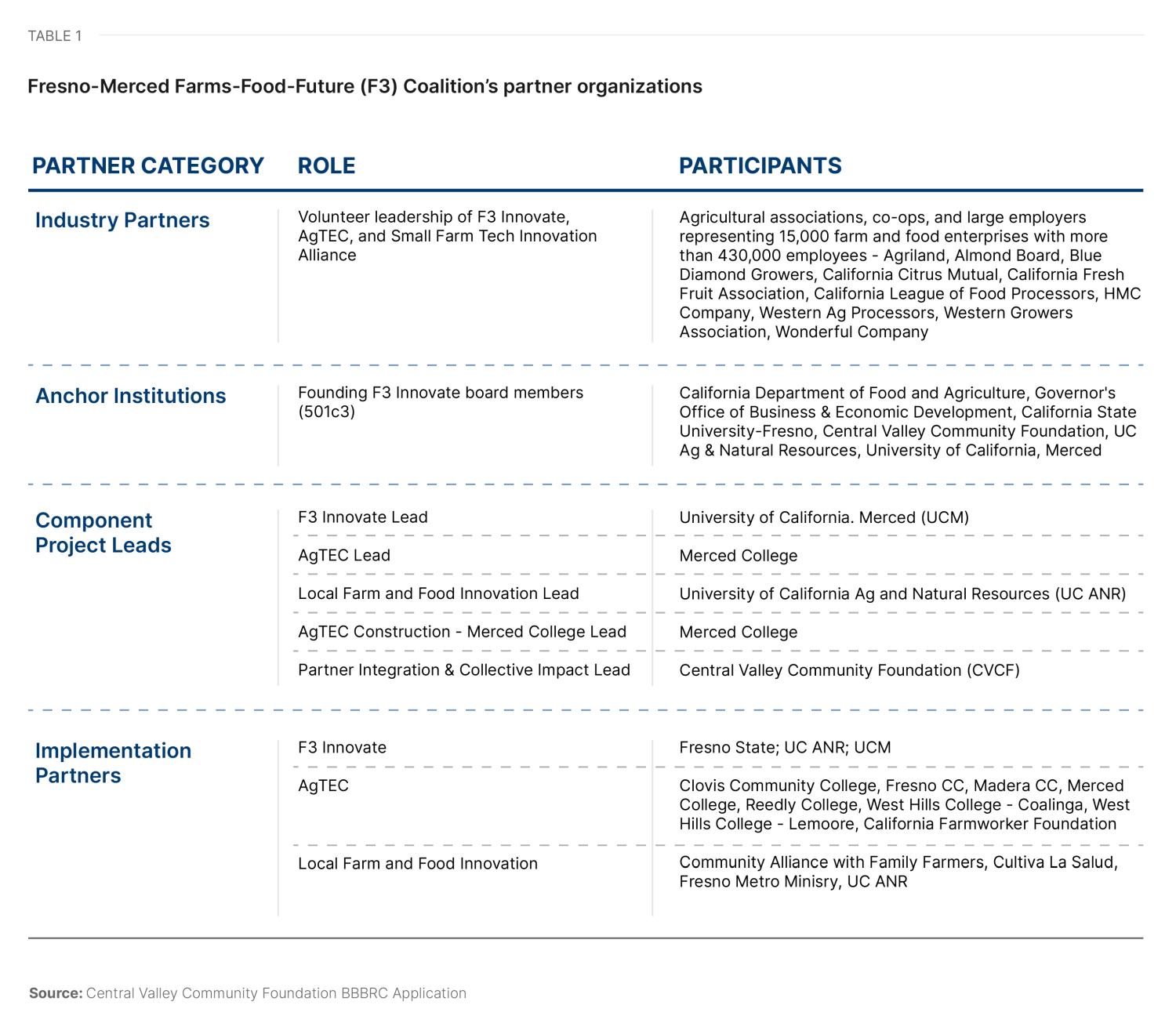

Even with these tensions, farming and farming-related industries remain the primary lifeline of the Central Valley economy, and its leaders are coalescing around a path forward that they believe can embrace agricultural technology while improving the economic and public health outcomes of existing Central Valley residents, farmers, farmworkers, and food entrepreneurs. This vision seeks to leverage the region’s distinct environmental, human capital, and civic assets (Figure 2) to ensure that agricultural technology can be a tool of inclusion and prosperity rather than one of worker displacement and/or exploitation. It builds on momentum from anchor institutions such as University of California, Merced; California State University, Fresno; University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources; and several regional community colleges that had previously been investing in agrifood tech research, facilities, and equipment in the years prior, and combines this groundwork with direct engagement with thousands of farmworkers and other food entrepreneurs in the Valley.

The reality is that we need to uplift and invest in the models of sustainability that we want to see… How are we creating these opportunities regionally for the folks that already live here? I think we landed in a healthy, balanced place of: We need to invest regionally in the opportunity to export technology and information globally, but don't lose sight of the folks that already live in the region and really investing with them.

A Central Valley-based farmworkers’ rights stakeholder

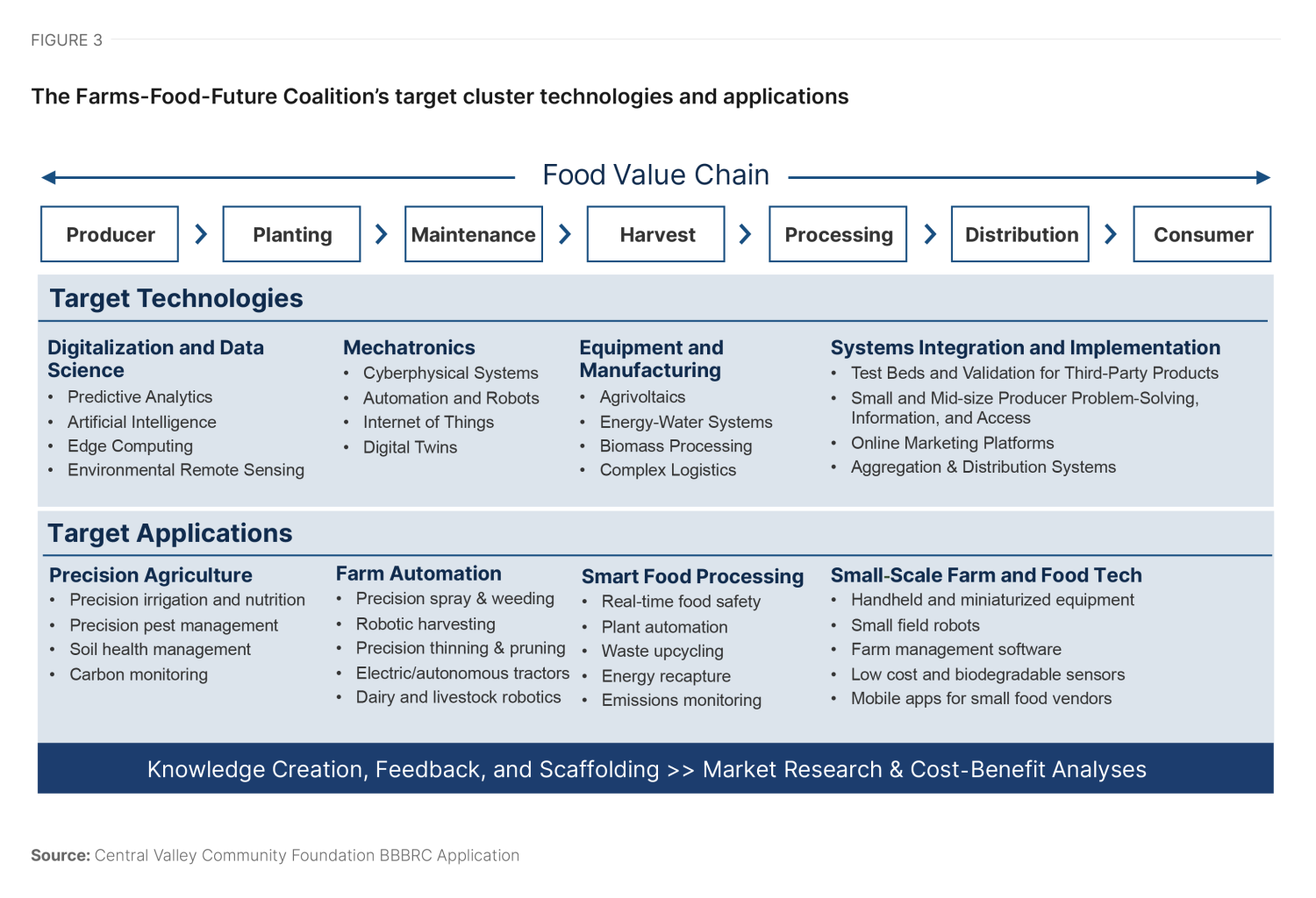

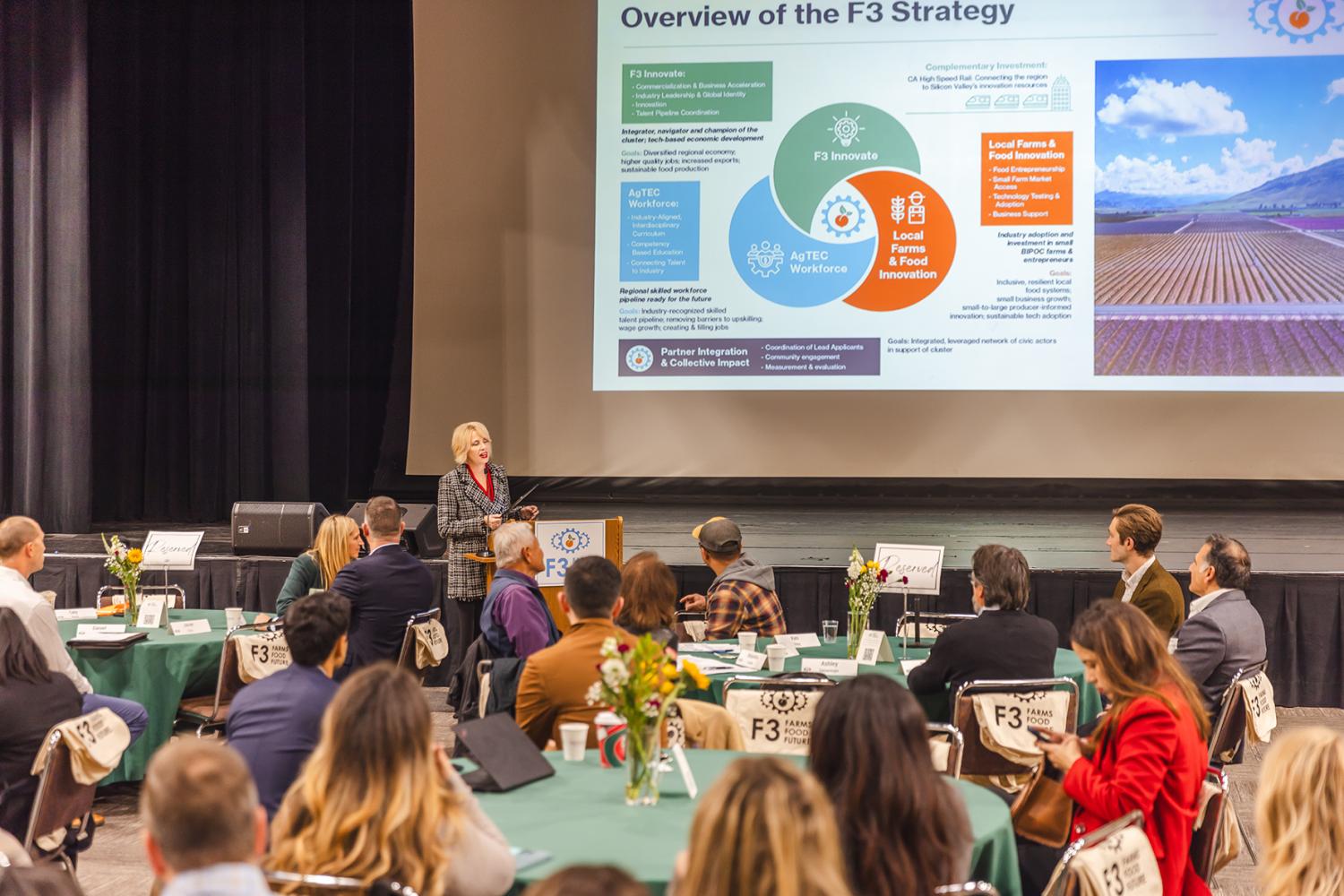

To achieve this vision—and help restore a region divided by economic, environmental, and health inequities—public, private, and civic sector leaders in the Central Valley formed the Farms-Food-Future (F3) Coalition, which aims to leverage agricultural technology to achieve three objectives: 1) develop and commercialize solutions for climate-adaptive food production; 2) create quality jobs across all skills levels for Central Valley residents; and 3) engage underserved small farmers and food entrepreneurs in technology development and adoption as well as new market access (Figure 3). Taken together, the coalition’s efforts seek to transform the Central Valley region into a sustainable global hub for climate-adaptive agricultural production, while growing and sustaining quality jobs for residents across all skill levels.

Coalition formation

The origins of the coalition

The F3 Coalition is unique not only for receiving the largest BBBRC award out of the 21 grantees, but also for being led by a community foundation with the convening power to align the often disparate interests of farmworkers, environmentalists, industry, and anchor institutions into a bold ag-tech vision rooted in principles of equity, inclusion, and environmental sustainability.

F3 stakeholders attribute the success of their BBBRC application to three primary factors: 1) the Central Valley Community Foundation’s (CVCF) change in leadership and strategic direction over the last decade; 2) the groundwork laid by previous cross-sectoral economic development initiatives in the region, such as Fresno DRIVE; and 3) preexisting social justice and multidisciplinary movements that heavily influenced the BBBRC application to embrace farmworker and environmentalist priorities.

First, over the last decade, CVCF transitioned from a more traditional community foundation model reliant on its endowment into an organization with diversified funding sources focused on enhancing the region’s economic prosperity. Much of this change can be attributed to its most recent president and CEO, Ashley Swearengin, who joined CVCF in 2017 after serving as the mayor of Fresno from 2009 to 2016. Based on her experience working both in the public and private sectors in the region, Swearengin advocated for CVCF to adjust its funding model to secure additional resources that could help match the scale of the challenges Central Valley residents experience.

Community foundations should change to respond to the needs of the region and community… We have very small amounts of funding to grant each year, and we live in one of the poorest regions in the country. We could have either worked really hard to grow our endowment, and in 300 to 400 years from now, there might be a sizable enough endowment to accomplish systems-level change in this region. Or we could change the way we operate and no longer limit ourselves.

Ashley Swearengin, president and CEO of the Central Valley Community Foundation

By 2019, the CVCF board agreed that the foundation should pursue diversified sources of funding and focus on enhancing inclusive economic mobility in the Central Valley region. This helped lay the groundwork for CVCF leadership in other cross-sectoral initiatives such as Fresno DRIVE and, eventually, its successful application for the BBBRC award.

Building on the new CVCF leadership and previous research conducted by Fresno’s Regional Jobs Initiative (which identified manufacturing and food as two major clusters to expand export-oriented industries in the region), the region adopted Fresno DRIVE (Developing the Region’s Inclusive and Vibrant Economy) in 2020. DRIVE is a 10-year, $4 billion strategy anchored by 14 initiatives across economic development, human capital, and neighborhood development. Developed in conjunction with a 300-person steering committee and led by a 38-member executive committee, DRIVE was among the initiatives that inspired the state of California to create the statewide $600 million Community Economic Resilience Fund (recently renamed California Jobs First) to support regional economic development plans like DRIVE. It also directly laid the foundation for the state’s initial $32 million investment in seed funding for the F3 BBBRC application in 2021 ($14.25 million of which was provided as a direct match to the BBBRC proposals), as well as its subsequent $20 million investment in non-EDA-funded F3 priorities in 2022.

What the state did with Fresno DRIVE was certainly the beginning of them recognizing the potential of the Central Valley. Now, they're looking at it much larger, in a way that’s focused on an industry that has the potential to be the Silicon Valley for ag-tech. They’re building on decades of realizing that they’ve got to do more and not only invest in what’s already working, but also invest in the potential of R&D emerging industry in general.

A Central Valley-based anchor institution stakeholder

Finally, the F3 Coalition was invariably shaped by power-building movements from communities of color and environmentalist advocates in the region. These major lanes of community organizing predated both the DRIVE and F3 initiatives, leveraging their significant grassroots backing to shape the priorities included in both and ensure that the needs of workers and environmentalists were as front and center as the needs of industry and anchor institution partners.

For the last 10 to 15 years, there has been power-building movement in Fresno led by low-income and communities of color in the Central Valley. Independent of institutions like Fresno State and the Regional Jobs Initiative—and at the same time the worlds of these institutions were churning and reforming—there’s been a tremendous power-building movement that came up, almost despite of these institutions.

Ashley Swearengin, president and CEO of the Central Valley Community Foundation

When the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the BBBRC was first released in August 2021, leaders at CVCF brought the application to the Fresno DRIVE Steering Committee. Having already established a regional coalition with DRIVE and engaged in the community work needed to garner public sector and grassroots support for its priorities, CVCF was able to adapt the Steering Committee developed for DRIVE to form the basis for the F3 Coalition. It expanded the coalition to encompass the broader five-county region, including seven community colleges that serve as crucial workforce development providers in more remote and rural areas, as well as to further cement the representation of community voice and farmworkers with organizations such as the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (which previously launched legal battles against the use of the mechanical tomato harvester), California Farmworker Foundation, Cultiva La Salud, and Fresno Metro Ministry.

The community college is the lifeblood of the economy in many small rural communities in the Central San Joaquin Valley. If the community college does not adapt, these towns will decline along with it. It's not just about adapting to upskill the workforce and train new clients; failing to adapt threatens both the college's existence and the survival of the community.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

Project identification and selection

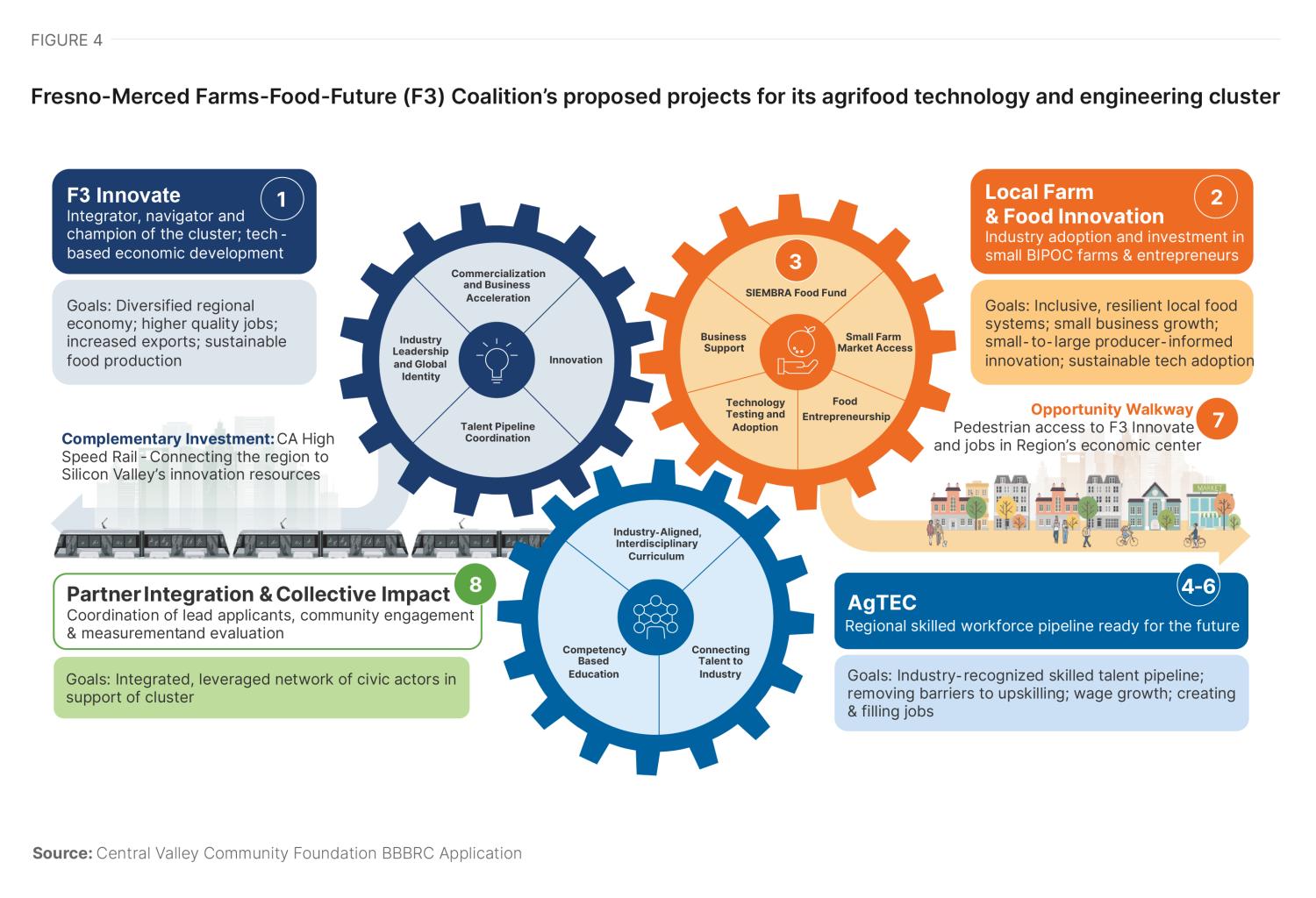

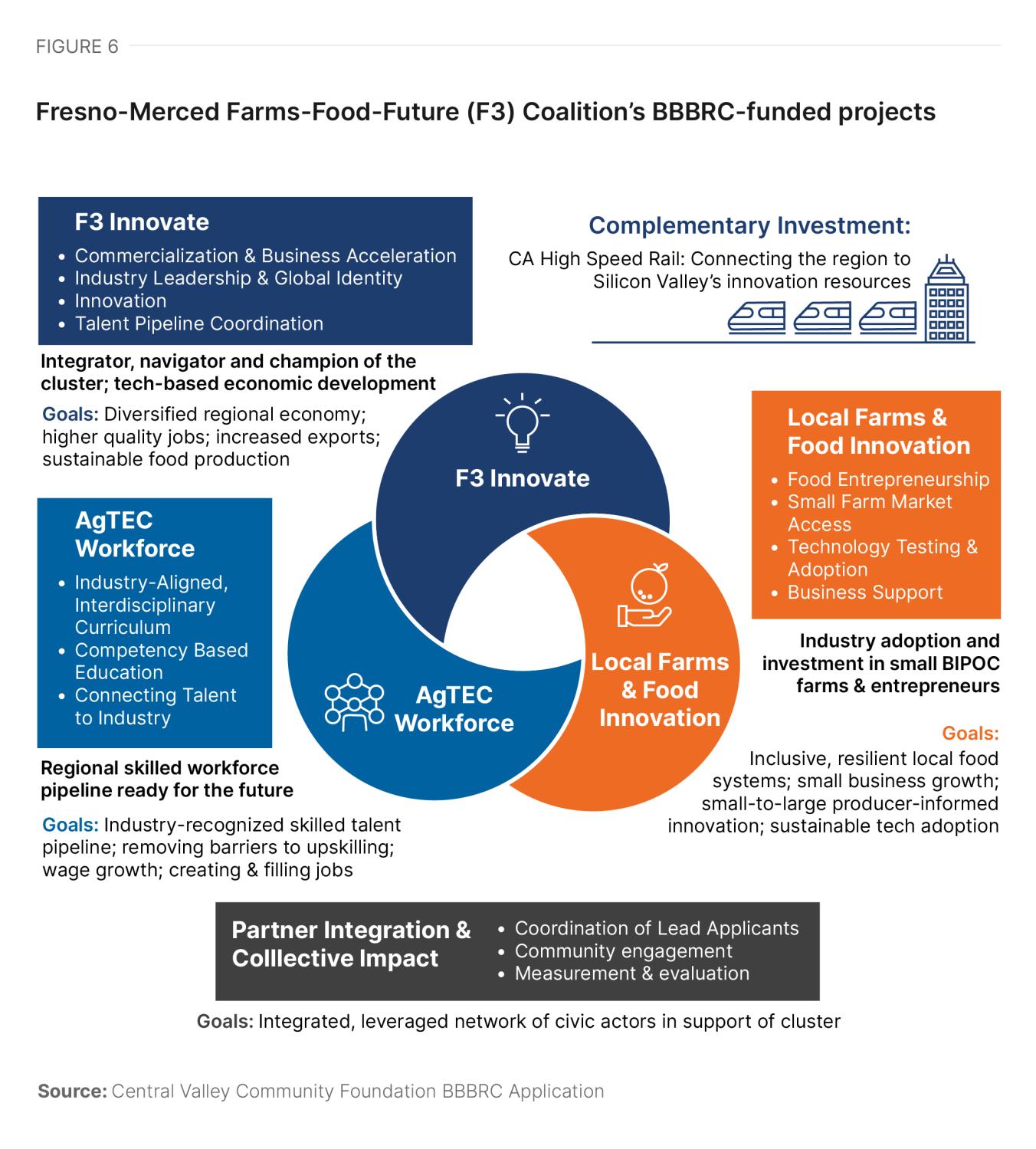

Based on the groundwork Fresno DRIVE laid, input from the expanded regional coalition, and early seed funding from the state of California, the F3 Coalition ultimately coalesced around a vision for climate-smart agrifood technology rooted in three interlocking “gears.” This “three-gear” portfolio took significant negotiation among partners and weeks of iteration on the strategies, but amounted to an initial request to the EDA for $100 million. The coalition ultimately received $65.1 million for five of the eight component projects.

Through the yearslong negotiation that we did to secure the $30 million from the state, we set the three-gear framework. Now, how do you turn that framework into the specific project portfolio? It was a very iterative, day-to-day, week-to-week kind of process.

Ashley Swearengin, president and CEO of the Central Valley Community Foundation

The following eight component projects, organized by “gear,” were included in the F3 Coalition’s BBBRC application (five of which were funded by the EDA):

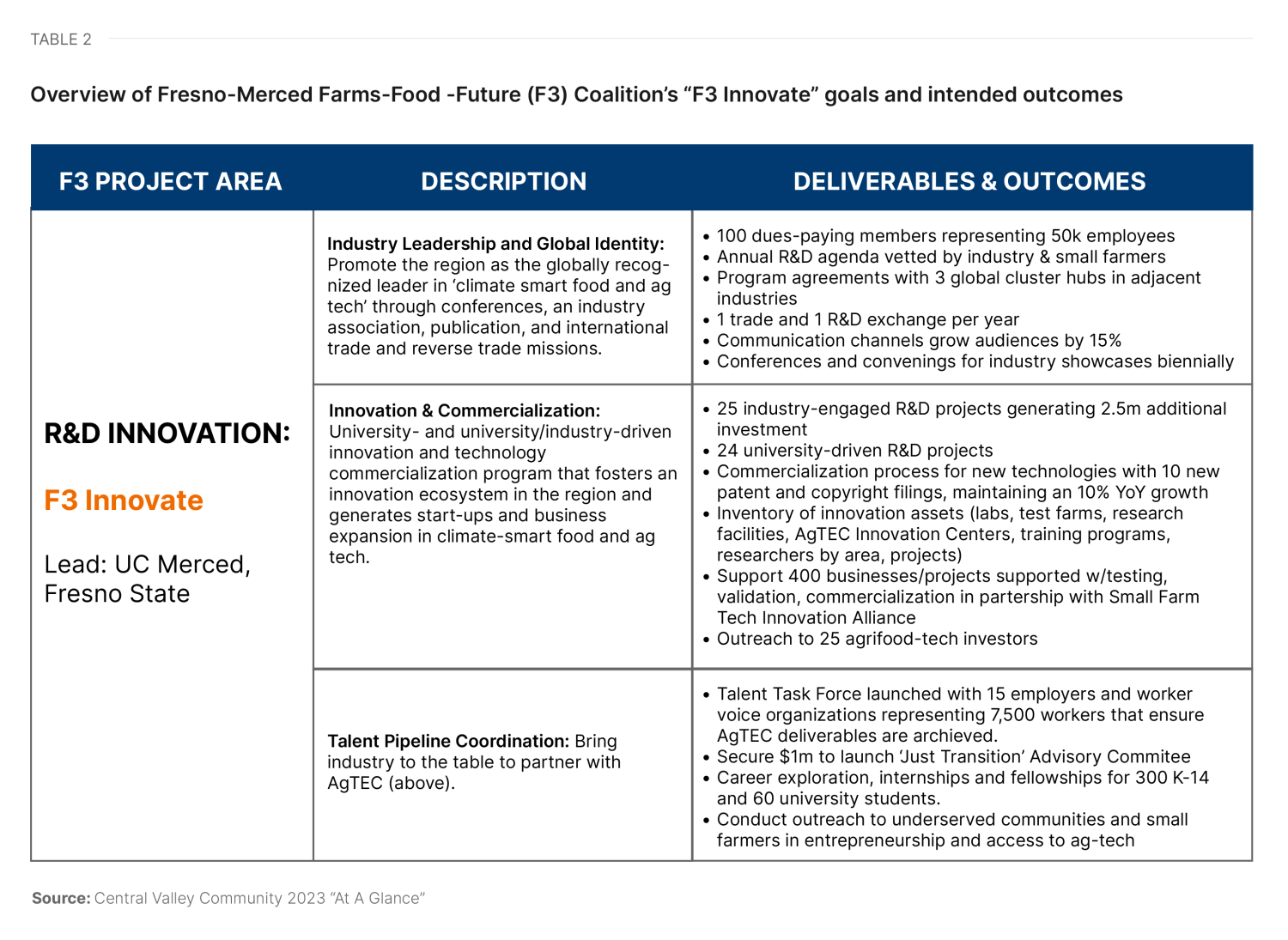

Research and Innovation Gear

- F3 Innovate (funded by the BBBRC at $20 million) aims to become the nation’s hub for climate-smart agrifood technology and engineering, anchored in a historic and long-neglected building in downtown Fresno. As a new nonprofit entity comprised of F3 Coalition partners, F3 Innovate will seek to achieve the following goals: 1) promote the Central Valley region as a globally recognized leader in climate-smart ag-tech through industry association, publications, conferences, and international trade; 2) drive university-industry-community partnerships to foster an innovation ecosystem and generate startups and business expansion; and 3) coordinate talent pipeline pathways by bringing industry to the table with study development programs.

Local Farm and Food Innovation Gear

- Local Farm and Food Innovation (funded by the BBBRC at $16 million) aims to stimulate inclusive economic prosperity and wealth-building for the Central Valley region’s small farmers and food entrepreneurs by offering capacity-building support, technical guidance, market access, and access to capital for underserved farmers and food entrepreneurs. More specifically, it will support the development of the San Joaquin Valley Agroecology Hub (an alliance of small farmers and BIPOC agrifood business owners who will adopt new sustainable technologies) and developing the Del Valle food hub (a physical space in Fresno for small-scale and underserved producers to sell their products and grow their businesses).

- SIEMBRA Food Fund (not funded by BBBRC) proposed establishing a revolving loan fund through the Fresno Area Hispanic Foundation to provide affordable and accessible financing to BIPOC-led small businesses across the Central Valley food system.

AgTEC Workforce Gear

- AgTEC Workforce Initiative (funded by the BBBRC at $15 million) seeks to develop a skilled, next-generation workforce in advanced, sustainable food production and manufacturing by aligning seven community colleges across the region (initially eight in the application prior to one’s withdrawal) to adopt an industry-approved curriculum and certificate program in Ag-tech and Competency-Based Education. Importantly, the AgTEC Workforce Initiative will prioritize upskilling incumbent farmworkers and will be rooted firmly in community engagement with farmworkers and industry partners.

Industry resoundingly said, 'We want to keep our workforce, train them, and pay them higher wages. We have a labor shortage, but we need our workers to know this technology. They have Indigenous knowledge of the land; these are the people we want to retrain.' So, hearing this from them helped dispel the myth that ‘[industry] is trying to get rid of all these people.' Really, industry is trying to balance the needs of production through automation, while retaining their workforce, but people often see it as an either/or situation.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

- Reedley College AgTEC Innovation Center (not funded by the BBBRC) was proposed to be a 20-acre hub on Reedley College’s farm housing ag-tech startups and providing Reedley students with work experience in agricultural technology through internships, job shadowing, and part-time employment.

- Merced Ag Innovation Center (funded by the BBBRC at $12 million) will be a 14,880 square feet food processing facility that provides interdisciplinary training for Merced College students in advanced, sustainable food production and food manufacturing, while fostering collaboration between university researchers, food processers, and manufacturing and logistics industries.

- Opportunity Walkway (not funded by BBBRC) was proposed to physically connect disadvantaged and disconnected communities in Southwest Fresno to economic opportunity by building a pedestrian trail and bicycle facility that connects these neighborhoods to the projected high-speed rail station, Downtown Fresno, and the proposed F3 Innovate building.

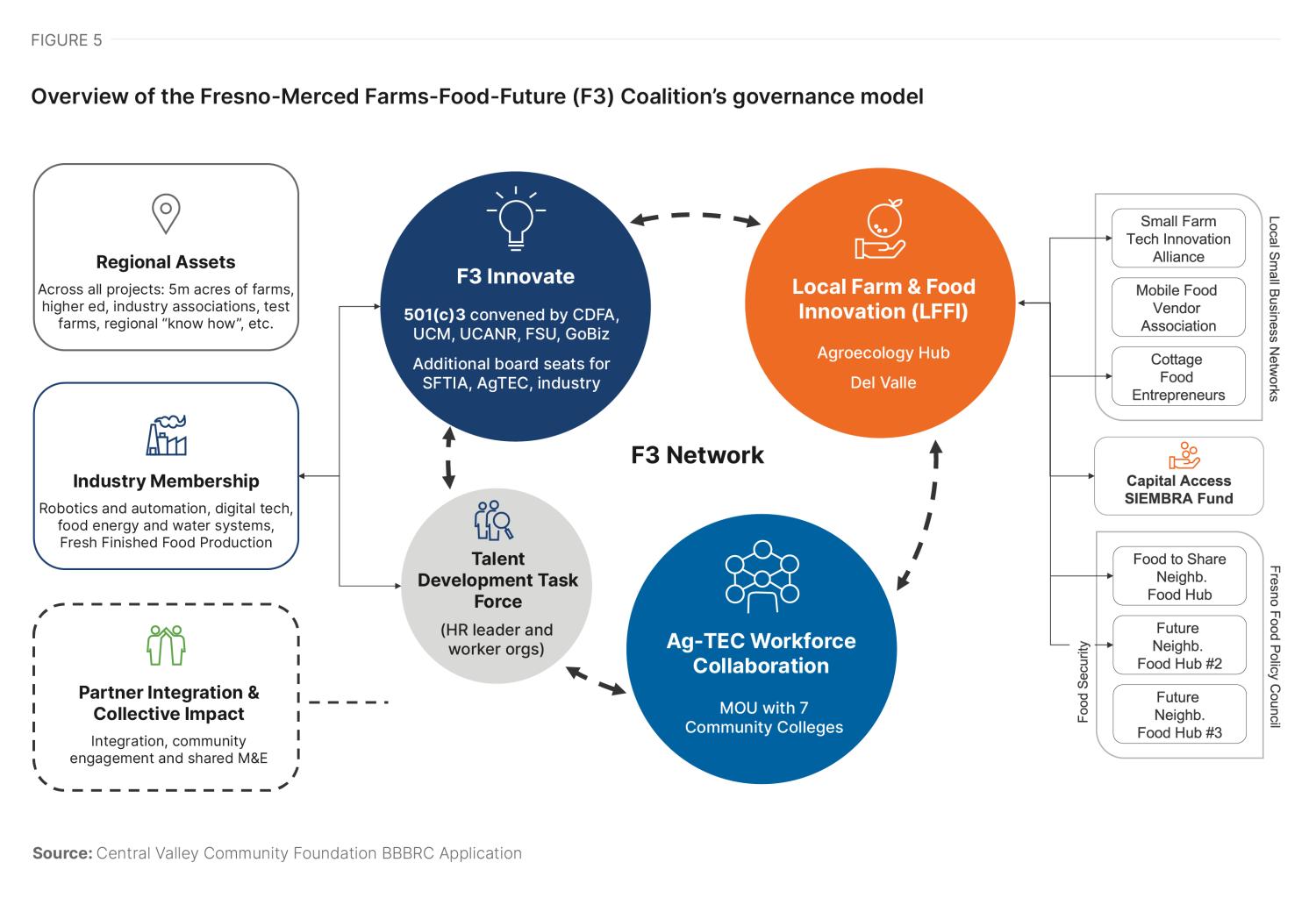

- Partner Integration (funded by the BBBRC at $2 million) funds CVCF to manage the governance and partner facilitation component of F3 to ensure investments across the portfolio are integrated, measured, and grounded in ongoing community engagement and usable data (Figure 7). Essentially, it establishes the civic infrastructure needed to “ensure that F3’s portfolio results are greater than the sum of their parts.”

With this proposed project portfolio, F3 was selected as one of the BBBRC’s 60 Phase 2 finalists (out of 529 coalitions competing for this designation in Phase 1). Since Phase 2 funding requests exceeded the BBBRC’s available resources, the EDA gave all Phase 2 finalists, including F3, the opportunity to reduce their budgets. The group submitted a revised proposal for all eight projects, and the Investment Review Committee selected five for implementation awards. Ultimately, the SIEMBRA Food Fund and Opportunity Walkway were cut from the BBBRC portfolio. While coalition members were disappointed, they described recognizing that the two unfunded projects had promising avenues to receive funding from other sources, and therefore felt like the core of the project portfolio remained intact.

With five projects ultimately selected for federal funding, the F3 Coalition has spent the last year implementing each to set its “three gears” up for success (Figure 5).

Embedding equity into the strategy

One of the EDA’s top priorities for allocating BBBRC funds was equity, which the Biden administration defines as “investments that directly benefit 1) one or more traditionally underserved populations, including but not limited to women, Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders or 2) underserved communities within geographies that have been systemically and/or systematically denied a full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic prosperity such as Tribal Lands, Persistent Poverty Counties, and rural areas with demonstrated, historical underservice.”

F3 prioritized equity in its coalition strategy and project portfolio through three primary means. First, F3 built on months of community engagement conducted during the Fresno DRIVE process and expanded its coalition to be inclusive of the region writ large, fully engaging community-centered organizations and outer-region community colleges in the process. For example, to ensure the representation of farmworkers who may not be able to participate in a formal coalition structure, they conducted several engagement activities, including surveys, six outreach convenings, and numerous informal conversations with workers to ensure meaningful farmworker engagement as an integral foundation of the coalition itself.

For three months, we conducted a robust community engagement process. We, along with our partners, gathered hundreds of mobile food vendors and interviewed farmworkers in the fields. We had honest conversations with them, and it became resoundingly clear that people wanted training. They said things like, ‘We want to learn the technology. We don't want to do this back-breaking labor, but we're scared of school. How can we do it in Spanish?’ This was a common sentiment.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

Second, F3 designed two of its three gears to be firmly grounded in principles of equity and inclusion. The Local Farm and Food Innovation gear, for example, is meant to be the portfolio’s “equity anchor” in its mission to directly grow and support small-scale BIPOC farmers and food entrepreneurs in the region. Additionally, its AgTEC Workforce gear is designed to be directly informed by incumbent farmworkers’ needs in order to create more inclusive pathways for upskilling workers—building in two rounds of surveys with thousands of farmworkers to ensure that the ag-tech curriculum is shaped by their desires and identifies barriers to opportunity to enhance their pathways to opportunity.

Technology advancement is rapidly transforming the world, and the ag industry is not exempt from that change. But, change also presents an opportunity for farmworkers to upskill, to have opportunities for a better life, a better job, and more money by learning how to operate the technology coming into the fields now. This is why we are developing the AgTEC Workforce program. After all, farmworkers are the experts on the fields and they can become the best operators of the technology being deployed, particularly with the right support. Farmworkers have the deepest understanding of agricultural practices and Mother Nature, and therefore, they can become the ideal connectors between technology and agriculture.

Cesar Lucio, regional economic competitiveness officer, Central Valley Community Foundation

Finally, the vision of F3 itself—to secure a just transition for a persistently poor, environmentally harmed, and food-insecure region that supplies the bulk of the nation’s produce—is one that cannot be separated from principles of equity and inclusion.

Implementing the strategy

Early implementation: Successes and obstacles

Of the implementation activities underway across F3’s funded projects, the coalition has garnered early successes in three key priorities while overcoming significant barriers that often make this work difficult in distressed regions. These early successes are:

- Fostering regional and state support for inclusive, climate-smart agricultural innovation. In a region highly divided by extractive agricultural production, devastating levels of food and environmental insecurity among workers and residents, and deeply rooted tensions between industry, farmworkers, and environmentalists, one of the strongest early wins for the F3 Coalition was its ability to align often adversarial actors around a shared regional vision for embracing agricultural technology that both improves economic outcomes for residents and solidifies the Central Valley region as an agricultural hub of climate-smart production.

I think F3 was one of the most challenging initiatives to bring together. When you provide so much of the nation's vegetables and produce, you can't just disrupt and rebuild that foundation without threatening the entire global food system. This is our core industry. Industry representatives say, 'We feed the nation.' Academia responds with, 'Yes, but how can we do it better using technology?' Meanwhile, environmental groups raise concerns like, 'We have the worst air quality and can't even get clean water.' All these issues converged in one room, and we had to find common ground and move forward on agreed solutions. It's still incredibly nuanced and difficult, and it's not a one-time effort. The relationships and ecosystem built with these partners require continuous and long-term engagement to keep working together on these solutions; otherwise, it's too easy to revert to our silos.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

Moreover, this equity-focused vision inspired unprecedented state recognition of the Central Valley region’s statewide and global economic importance alongside other major California economic anchors like the San Francisco Bay Area and Greater Los Angeles—with the state of California being an earlier investor of $32 million to help seed F3-related projects.

- Establishing a regional workforce ecosystem rooted in farmworker and community voice. F3’s project portfolio hinges upon building and sustaining an inclusive local workforce skilled in advanced food production and manufacturing to support the region in becoming a global leader in climate-adaptive food production. The primary strategy through which the coalition seeks to accomplish this goal is through its AgTEC Workforce Initiative—a competency-based educational curriculum designed to upskill incumbent farmworkers, co-developed and co-implemented across seven of the region’s community colleges.

In the first year of implementation, the AgTEC Workforce Initiative secured significant early wins, but was not without its challenges. For instance, a key early win was its ability to engage over 12,000 farmworkers and directly base the curriculum on this feedback and the often ignored realities of farmworkers. During the same period, they were also able to align and coordinate seven community colleges to co-create and co-endorse a standard ag-tech competency-based education (CBE) curriculum, to be implemented in classrooms in fall 2024—outpacing the California Community Colleges’ Vision 2030 plan for incorporating CBE in the community college curriculum. In doing so, coalition partners were able to identify the challenges that farmworkers face in acquiring and sustaining agricultural jobs, and were subsequently asked to be a demonstration project in the Vision 2030 plan.

When we talked to farmworkers, they shared concerns like, ‘I have to share a car with my neighbor, so I need flexibility on when I can use it. It’s not that I don’t have reliable transportation; I just need flexibility.’ Understanding nuances like this is crucial. The survey also revealed that most farmworkers had a sixth-grade level of formal education, which was eye-opening for many. However, this didn't mean they lacked skills or intelligence; they simply lacked experience with formal education. These were some of the most powerful insights from the survey. It also drove us to significantly change our approach, embracing a human-centered design. The 12,000 voices in the survey essentially brought the program to life.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

The AgTEC workforce strategy is still experiencing challenges, including overcoming broadband access and documentation barriers for farmworker trainees, obtaining buy-in from California community colleges to embrace CBE, and cementing industry partnerships in an often adversarial environment for both workers and industry. Still, stakeholders described achieving early alignment across all involved sectors to help ensure the groundwork of trust is laid for the workforce strategy to succeed in its mission of meeting both workers’ and industry needs.

Industry feedback was clear: 'We don't need an expert in everything. We want someone with a broad understanding of various areas. As technology evolves rapidly, we need someone who can troubleshoot and learn new systems, not someone repeatedly trained on a single system. That's not the kind of worker we're aiming to develop anymore.' This perspective drove us to design a program that covers the entire value chain. It represented a significant shift from the traditional approach of community colleges, which typically focus on specialized training. The labor market data didn't initially support this new type of employee, making it challenging for community colleges to adapt. However, having industry voices at the table made it possible to build the program in this way.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

- Forming a new governance entity for long-term sustainability of F3’s goals. Finally, the F3 Coalition stands out among BBBRC awardees for successfully establishing a new and long-term governance entity designed to ensure sustainability and accountability for coalition-wide priorities, while also enabling other lead implementors to complete their coalition project priorities without the burden of taking on uncompensated management and governance duties. In the first year of implementation, the coalition formally established a new 501(c)(3) entity, F3 Innovate, —sponsored by the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development; California Department of Food and Agriculture, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources; University of California, Merced; California State University, Fresno; and the Central Valley Community Foundation—with the stated goals of promoting the Central Valley as a globally recognized leader in climate-smart ag-tech, facilitating university-industry-community partnerships, and coordinating talent pipeline pathways to foster an innovation ecosystem.

Already, F3 Innovate has identified and convened a board to guide the direction of the new entity. Next steps include hiring a permanent CEO and finalizing agreements for revitalizing a historic downtown Fresno building into the organization’s new headquarters. This long-term governance mission demonstrates the unique role that community foundations can play as long-term stewards for inclusive growth strategies.

Organizing coalition-wide to deliver equity

The BBBRC award strengthened and solidified the partnerships formed during previous regional initiatives, including Fresno DRIVE, to fund a bold and cohesive roadmap for transitioning the region’s agricultural economy into one rooted in inclusive workforce development, environmental sustainability, and long-term sustainability.

F3’s coalition governance structure builds upon DRIVE’s steering committee, which encompassed hundreds of civic, business, and community organizations across the region. But it also relies on the regional leadership of CVCF to create a long-term governance entity, F3 Innovate, as the region’s sustainable hub for achieving, tracking, and scaling the impacts of the coalition writ large. The coalition’s distributive governance mechanism—meaning that it relies on both inclusive engagement practices (such as farmworker surveys and industry input) and formal decisionmaking bodies (such as the DRIVE steering committee)—ensures a structured and inclusive process that builds on the unique role that community foundations can play in seeding regional cluster initiatives without insisting upon long-term control.

CVCF provides the rocket boosters that get things launched, and then we fall back. That’s because we're trying to build this ecosystem that goes on in perpetuity, and I think F3 Innovate will be the focal point that continues to pull all this work forward. The formal governance is going to be its own independent nonprofit corporation, so we made sure to stipulate that the board seats would be representative of the broad coalition portfolio.

Ashley Swearengin, president and CEO of the Central Valley Community Foundation

Implications

While there are still multiple years left in the BBBRC, F3’s progress so far provides critical insights for economic and community leaders—particularly those in economically distressed regions threatened by the disproportionate impacts of climate change.

First, the F3 Coalition demonstrates the critical role that community foundations and other nonprofit intermediaries can play in convening and sustaining transformative regional economic development initiatives. Central Valley stakeholders consistently reiterated that the F3 coalition—which represents a historic collaboration among often adversarial institutions such as farmworkers, industry, environmentalists, ag-tech practitioners, and competing anchor institutions—could not have been possible without a neutral convener and mediator like a community foundation. Stakeholders emphasized the crucial role that CVCF played in ensuring that the perspectives of small BIPOC farmers and farmworkers were fundamentally valued as much, if not more, than industry partners—which inspired a wider set of champions to support and facilitate a vision that would have otherwise been seen as politically unachievable in the region.

I would advise regions to think more about their work as community mediation and conflict resolution than economic development. This world of inclusive economic development needs to develop a cadre of people who are skilled at community-based conflict resolution and mediation in the economic realm.

Ashley Swearengin, president and CEO of the Central Valley Community Foundation

Second, the F3 case study reiterates the importance of building on previous initiatives to grow and scale a transformative economic and environmental justice vision. For instance, much of the groundwork for F3’s success was rooted in the trust, engagement, and coalition-building achieved during the Fresno DRIVE initiative. The region’s ability to swiftly adapt its DRIVE coalition to “think bigger” about one of its 14 pillars—F3—and win an award like the BBBRC is emblematic of that success.

Finally, the F3 Coalition demonstrates that catalytic role that state funding can have on the success of regional cluster initiatives. Notably, the state of California provided an early commitment of $32 million in seed funding for F3-related projects (and $14.25 million as a direct match for BBBRC projects), while supplementing an additional $20 million match to the coalition in its next phase.”

F3 leadership considers California’s commitments to the coalition as a demonstration of the state becoming a critical champion for inclusive economic development and climate-smart technology in the Central Valley.

I've been truly appreciative of the state's recognition that we have something unique and incredibly promising here in the Central Valley of California. We've long said, 'We feed the world.' The state's initial investment made us eligible to participate in the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and continues to drive unprecedented investments in R&D and workforce training. This has the potential to become a force multiplier for both the region and the state. This forward-thinking approach is refreshing, and I am incredibly grateful that the state continues to show up as a committed partner.

Karen Aceves, founder and CEO of ARKEN Strategies

Conclusion

Though the full impact of the F3 Coalition’s BBBRC strategy will likely not be known for many years, its impact on the Central Valley region so far has been extremely promising. While the coalition will need to identify new funding resources to sustain its successes once the BBBRC is over, its work to date is a model for justly transitioning from an economy dominated by poor pay and inadequate workers’ rights to a region with sustainable pathways for shared prosperity and inclusive community well-being.

EDA case study series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publications are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or other scholars.

Brookings recognizes the value it provides in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its funders reflect this commitment.

The authors thank Alex Jones, Bernadette Grafton, Ilana Valinsky, Ryan Zamarripa, Suyog Padgaonkar, Scott Andes, and Justin Tooley from the Economic Development Administration for their insights into the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and for their guidance throughout the development of this case study. For their comments and advice on drafts of this paper, the authors also thank our colleagues Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, Mayu Takeuchi, and Rachel Barker, as well as Cesar Lucio, Ashley Swearengin (Central Valley Community Foundation), and Karen Aceves (ARKEN Strategies). The authors also thank all local leaders, community-based organizations, economic development practitioners, regional intermediaries, higher education institutions, industry representatives, and other coalition members who participated in informational interviews and site visits throughout this project, and who provided feedback on the research insights and policy recommendations detailed in this report.

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

About Brookings Metro

Brookings Metro collaborates with local leaders to transform original research insights into policy and practical solutions that scale nationally, serving more communities. Our affirmative vision is one in which every community in our nation can be prosperous, just, and resilient, no matter its starting point. To learn more, visit www.brookings.edu/metro.

-

Footnotes

- Economic Development Administration. “FY 2021 American Rescue Plan Act Build Back Better Regional Challenge Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (ARPA BBBRC NOFO).” U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better

- Ibid.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).