The one-minute version of this case study

- The Indigenous Finance Industry is essential for economic growth, but it has faced historic and present-day underinvestment. Owing to hundreds of years of harmful government policies, Native Americans living on tribal land have the lowest levels of household wealth in the United States and face structural barriers to capital access that diminish entrepreneurship, business growth, and wealth-building. A more functional, accessible, and equitable Indigenous-led finance industry can enable Native entrepreneurs and business owners to start and expand operations and, in turn, provide more jobs for tribal citizens, boost economic activity on tribal land, and build wealth for tribal business owners.

- The Mountain | Plains Regional Native CDFI Coalition (Mountain | Plains Coalition) is utilizing the Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) to fortify a robust regional Indigenous Finance Industry. Founded to reverse patterns of historic disinvestment, Native community development financial institutions (Native CDFIs) provide specialized financial and cultural knowledge to strengthen tribal economies. The Mountain | Plains Coalition is an Indigenous- and woman-led effort to restore financial self-sufficiency and enhance economic growth for Indigenous Peoples in North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming. Through $45 million in federal investment, this network of nine CDFIs and one community development corporation (CDC) is working to not only address and overcome structural barriers to capital access, but also leverage existing Indigenous knowledge, institutions, and relationships to build a robust and inclusive finance cluster that aligns with community priorities and supports economic growth.

- Equitable process and outcomes are both key to inclusion. This case study explores the design and implementation of the Mountain | Plains Coalition’s holistic approach to cluster-building. The coalition is using Indigenous ways of working and a consensus-driven governance model to implement five projects, including the creation of a regional industry growth plan with supporting resources and peer-to-peer learning; workforce and shared services development for the Indigenous Finance Industry; the construction of buildings to support business development on tribal land; and the launch of the second-largest revolving loan fund in the Economic Development Administration’s (EDA) history.

- Place-based policies can deliver much-needed investment to Indian Country, but federal rules, regulations, and processes need to adapt to the distinct context of tribal economies. During 2023 and 2024, Mountain | Plains Coalition leaders and EDA officials entered into a joint problem-solving process to address several early hurdles to implementation. This case study offers lessons for both Native-led organizations and other historically underrepresented communities interested in accessing large federal grants, and for federal agencies that want to invest in and partner with those communities.

Before reading this case study: What is the Build Back Better Regional Challenge?

This brief overview of the program provides useful context before reading this case study.

In July 2021, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) launched the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) through a Notice of Funding Opportunity that outlined a two-phase competition.1 Through its Phase 1 activities, the EDA issued an open call for concept proposals that outlined a high-level vision for a “transformational economic development strategy.” The thesis was that regions would identify an industry cluster opportunity; design “3-8 tightly aligned projects” to support that cluster; build a coalition to “integrate cluster development efforts across a diverse array of communities and stakeholders”; and ensure that these collective efforts advance equity by supporting economically disadvantaged communities.2

In Phase 1, 529 coalitions submitted high-level concept proposals that outlined a vision for the cluster, a high-level description of potential projects, and the key institutions involved in the coalition. After receiving Phase 1 concept proposals, the EDA undertook two months of review to determine which coalitions would be awarded $500,000 technical assistance grants and invited to apply for Phase 2 funding. Those resources enabled a hyper-intensive planning sprint between December 2021 and March 2022. During this period, each of the 60 finalist coalitions expanded their five-page concept proposal into an overview narrative and project proposals that outlined their approach, key assets and institutions, the portfolio of projects and their expected outcomes, and matching resources to complement the EDA grant.

Ultimately, the 60 coalitions submitted funding requests well beyond the BBBRC’s $1 billion allocation. The average Phase 2 funding request submitted to the EDA was approximately $75 million, while the average award amount available in the competition budget was approximately $50 million. Given this gap, in May 2022 all 60 applicants were offered the opportunity to prioritize funding through a budget request reduction process after applications were received. Then, an Investment Review Committee (IRC) assessed all completed applications and made recommendations. In some cases, the EDA ultimately selected a subset of component projects for funding or funded component projects at a reduced level, requiring applicants to modify projects during the award process. In September 2022, the EDA selected 21 of the 60 coalitions for implementation awards, ranging in size from $25 million to $65 million, to be spent over a five-year period.

The Mountain | Plains Regional Native CDFI Coalition (Mountain | Plains Coalition) is an Indigenous- and woman-led coalition aiming to restore financial self-sufficiency and enhance economic growth for the Indigenous Peoples of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) are private sector financial intermediaries that lend with community development as their primary mission. CDFIs have a variety of structures and goals. Some offer an array of credit products, while others specialize in specific types of lending. Within the financial sector, Native CDFIs, which primarily serve Native American borrowers and reservation economies, play a unique and important role.

The economic challenges that Native nations face today stem from hundreds of years of public policies that were designed to strip Indigenous Peoples of their land and sovereignty, assimilate them into mainstream American society, and ultimately end their existence as independent nations and cultures. Policies from the 19th and 20th centuries to dissolve the collective tribal land ownership and forcibly remove land from Indigenous control have had a cascading effect on Native economies.

Today, most reservations are a mishmash of different land ownership, with some owned by the federal government (called “trust land”), and some owned by tribes, tribal citizens, and non-Native people alike, with various levels of restriction on their sale, transfer, or ability to lease. As a result of this jumble of land ownership and the complexities it can bring, many mainstream financial institutions choose not to do business on tribal land.

Restrictions on land ownership also create discriminatory access to wealth-building tools. For example, tribal citizens living on trust land cannot own the land underneath their home. Because the land is owned by the federal government rather than the homeowner, their homes become a depreciating asset rather than a wealth-building vehicle. Being cut out of the primary method by which most Americans build wealth has, over multiple generations, compounded the wealth disparities that Native Americans face.

This fractured landscape of Native land ownership, combined with the refusal of mainstream financial institutions to lend on Native land, gave rise to the Native CDFI movement, which was one of the critical developments in the creation of the broader national CDFI movement. Today, Native CDFIs maintain a unique distinction within the CDFI landscape as the only group of CDFIs designated to support a specific group of people.

In their work, Native CDFIs are distinct from other financial institutions along three lines. First, Native CDFIs are uniquely well suited for supporting the cultural needs of their communities. As discussed later in this case study, many Native American communities view credit fundamentally differently than the dominant American culture, because of their distinct cultural values and history. Native CDFIs, which are overwhelmingly Native-led, are well positioned to meet Native borrowers where they are, understand their perspective, and gain their trust.

Second, Native CDFIs serve as critical anchor institutions and community pillars. Native CDFIs are often the sole provider of financial products for residents in a community, many of which are among the most remote places in the U.S. As such, many Native CDFIs offer an array of financial products, and thus underpin their communities’ economies. Moreover, Native CDFIs operate from a relationship-based lending model. Rather than simply provide financial products to credit-worthy borrowers, they often spend a significant amount of time getting clients to a position of being viable borrowers. For many residents of tribal reservations who have undergone generations of trauma, including financial trauma, this relationship-based approach can be life-changing.

Third, Native CDFIs have implemented new financial products for the reservation context, such as leasehold mortgages that allow tribal citizens to collateralize trust land. These types of products require substantial time and effort to create, and have a relatively small market and limited financial upside. As such, they don’t often make sense for large commercial banks to take on, meaning Native CDFIs are often their only providers.

Today, there are a range of CDFIs operating in the Mountain-Plains region that provide these functions to borrowers. The CDFIs of the Mountain | Plains Coalition serve borrowers across a four-state region comprised of North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming—four of the least populated states in the nation, but with some of the highest concentrations of Native American people. The counties overlaying reservations in the region have some of the highest levels of persistent poverty nationally. The area the coalition serves represents 20 reservations (Fort Berthold, Spirit Lake, and Turtle Mountain in North Dakota; Cheyenne River, Crow Creek, Flandreau, Lake Traverse, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock, and Yankton in South Dakota; Blackfeet, Crow, Flathead, Fort Belknap, Fort Peck, Northern Cheyenne, and Rocky Boy’s in Montana; and Wind River in Wyoming). Sixty-two percent of the population within these reservation communities is Native American.

Background

Coalition formation

This section explores how the CDFIs that comprise the Mountain | Plains Coalition came together to apply for BBBRC funding and develop a project portfolio to bolster growth and wealth-building in tribal economies. This coalition’s project portfolio will be of interest to organizations serving Native American communities, those operating in mission lending and financial services more broadly, and leaders in communities that the federal government has historically underinvested in, including communities of color and rural communities. It will also be of interest to federal agencies seeking to grow the number of Native American-led entities that apply for future large-scale federal place-based investments.

Aligning the coalition around a call to action

The Mountain | Plains Regional Native CDFI Coalition originally came together as a group of Native CDFIs aiming to support one another via sharing resources and best practices. The CDFIs met as a formal coalition for the first time in March 2020, but various coalition members had been collaborating in a more informal capacity for years beforehand.

Since CDFIs are nonprofit organizations, they don’t operate with the same profit- and competition-driven mindset as commercial banks. Rather than compete for a relatively small number of borrowers, the Native CDFIs involved in the coalition decided they could support the broadest number of people by collaborating with one another. Coalition members also mentioned that by working together to raise money as a coalition, the CDFIs would be able to gain access to capital that they couldn’t access as individual organizations.

The coalition’s first meeting in March 2020 coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. While this timing was coincidental, the pandemic gave coalition members increased reason to continue to meet and strengthen their ties. As members shifted their operations online and remote work became the norm, the coalition became a key connection point for the CDFIs to seek out and share emergency best practices on issues such as remote work, broadband access, and business supports to keep their operations running. The coalition also became a center for vital policy work, including their collective efforts to show that Native communities were excluded from pandemic-era economic programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). This experience provided the coalition with a significant reservoir of trust, which proved to be a substantial asset during the BBBRC application process.

The coalition itself is comprised of individual CDFIs, each serving unique communities and markets and contributing their own specific industry expertise. The coalition members are:

- Akiptan: Based in Eagle Butte, S.D., Akiptan is a national innovator in Native agricultural lending. By leveraging patient capital to strategically catalyze asset-building, Akiptan’s model grows the largest industry within rural Indigenous economies. Currently, South Dakota and Montana are Akiptan’s two largest markets.

- Black Hills Community Loan Fund: Based in Rapid City, S.D., Black Hills Community Loan Fund offers a variety of programs and services for entrepreneurs, businesses, individuals, and families across nine Lakota and Dakota Tribes in the He Sapa (Black Hills) region.

- Four Bands Community Fund: Based in Eagle Butte, S.D. and serving the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation, Four Bands is a national leader in innovating financial products to address the racial wealth divide, uniquely leveraging data and peer-to-peer partnership-building to impact systems change. Four Bands’ current portfolio supports small businesses, youth entrepreneurship, credit-building, and homeownership.

- Montana Native Growth Fund: Based in Hays, Mont., Montana Native Growth Fund (MNGF) builds strong, sustainable Indigenous communities with a whole-systems approach to lending. Known for their leadership in homeownership, MNGF serves the Fort Belknap Reservation and Native Americans in Montana.

- Mountain Plains Community Development Corporation: Based in Eagle Butte, S.D., the Mountain Plains Community Development Corporation (MPCDC) provides a variety of shared services and other non-physical infrastructure support to the CDFIs of the Mountain | Plains Coalition, and by extension supports all of the communities coalition members serve. MPCDC was established in 2023 as part of the scope of work for the coalition’s BBBRC Project 3: Non-Physical Infrastructure.

- NACDC Financial Services: Based in Browning, Mont. and working throughout that state, NACDC Financial Services removes barriers in Indian Country that prohibit the flow of capital and credit by addressing critical needs in Native communities.

- Native American Development Corporation: Based in Billings, Mont., Native American Development Corporation (NADC) serves Native American people and societies in Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota—focusing on entrepreneurs, individuals, families, and regions working toward self-sufficiency and economic and social stability through the core activity areas of technical assistance, business lending, health and wellness, and entrepreneurial advocacy and support.

- Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation: Based in Crow Agency, Mont. and serving the Crow Nation, Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation (Plenty Doors) creates thriving communities emphasizing a diverse economy while preserving the unique cultural and environmental qualities of the Apsáalooke (Crow People). An emerging fund, Plenty Doors recently launched its lending program to compliment community services.

- People’s Partner for Community Development: Based in Lame Deer, Mont., People’s Partner for Community Development (PPCD) bolsters reservation economies through strong connections to land, traditional values, and cultural history. PPCD provides financial opportunities to stimulate economic development by promoting self-sufficiency, self-determination, and an enhanced quality of life for reservation communities.

- Wind River Development Fund: Based in Fort Washakie, Wyo., Wind River Development Fund supports economic development on and near the Wind River Indian Reservation. A re-emerging fund, it leverages private and government partnerships to provide local entrepreneurs and businesses with access to capital, technical assistance, support, training, and professional capacity.

The coalition’s makeup also highlights the important leadership role of Native women. Of the coalition’s 10 organizations, nine are Native-led, and eight are led by Native American women.

An important takeaway for policymakers and federal economic development staff is that coalition members initially perceived the BBBRC program as out of reach, given the time needed to put together a competitive application, the anticipated number of applicants, and the federal government’s historical underinvestment in Indian Country. Coalition members worried that using all their capacity to apply for the BBBRC would preclude them from seeking funding from other sources that they were more likely to win. What ultimately nudged the coalition to move forward with its application was the potential for transformative investment: While the BBBRC put the coalition in competition with many applicants, it could also provide the critical mass of funding needed to significantly raise the growth trajectory of the region’s Indigenous Finance Industry.

Building an Indigenous Finance Industry was a natural choice for the coalition—capital access is an essential resource for economic development, but it historically has been in short supply in Native American communities. A robust finance industry has important downstream effects for tribal economies. With sufficient capital access, Native American businesses can acquire loans to start and expand operations. Doing so allows them to hire more people, which provides jobs for tribal citizens and supports economic activity in the form of direct, indirect, and induced spending on tribal land.

Project identification and selection

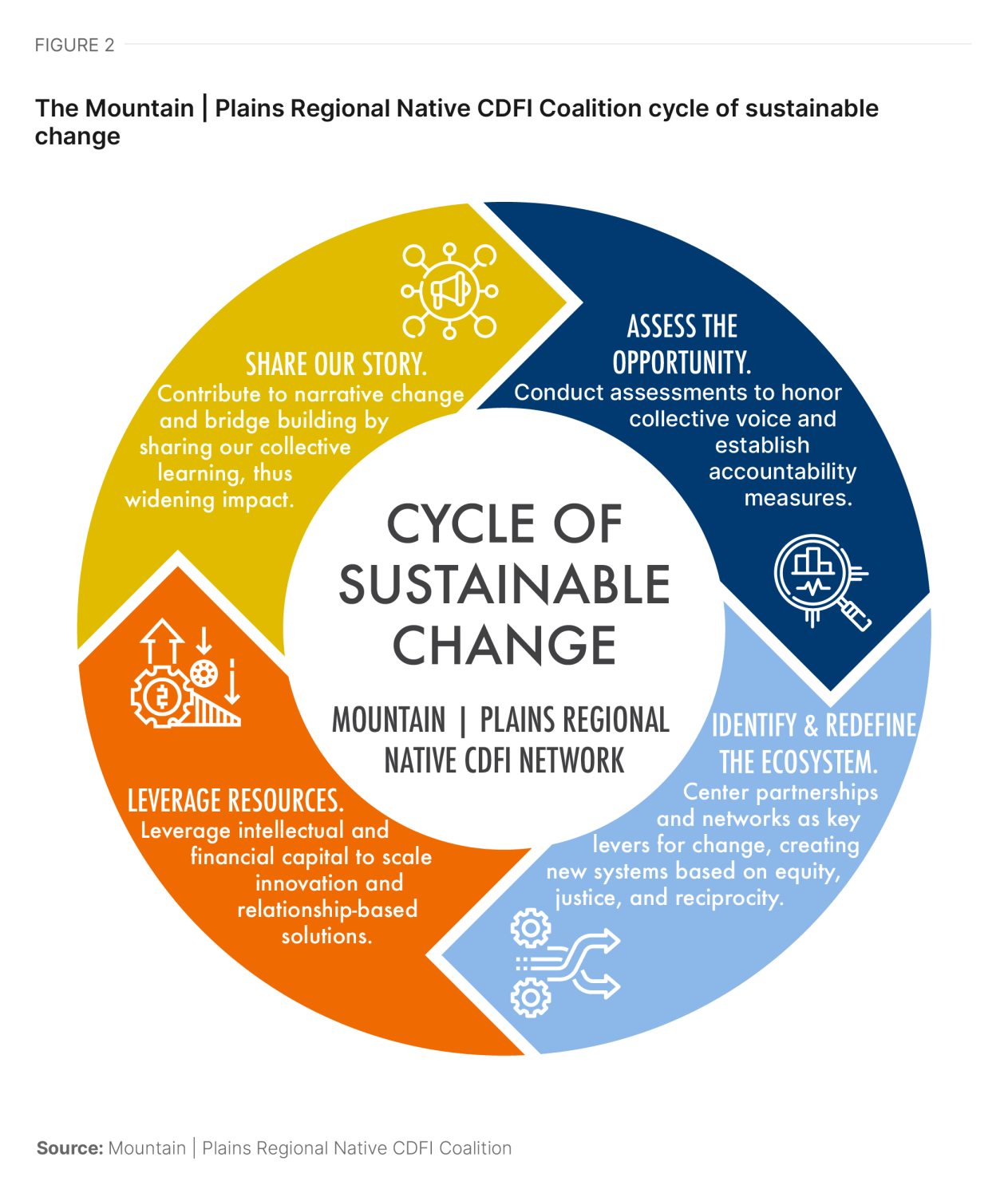

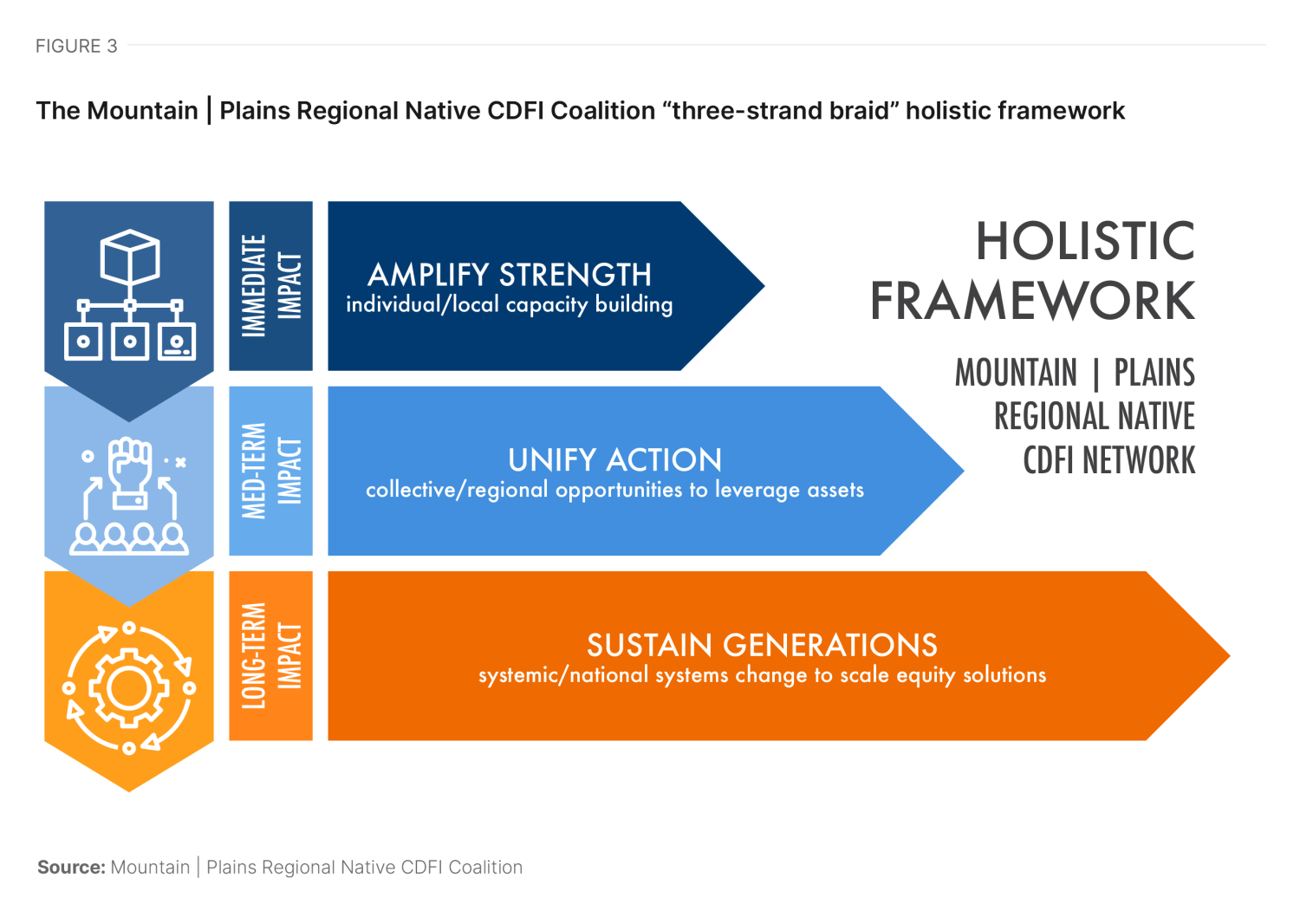

The coalition developed two foundational concepts to identify and select a portfolio of project-based investments to support the Indigenous Finance Industry: the cycle of sustainable change and the holistic framework (or “three-strand braid”). The cycle of sustainable change, shown in Figure 1, describes the four steps the coalition sees as essential for guiding systemic change. The cyclical process exemplifies how stakeholders must continuously work toward improving equity and justice. To create its holistic framework, shown in Figure 2, the coalition mapped each proposed project to three fundamental principles: 1) amplify the strength of individual coalition members and their communities; 2) unify the action of the coalition and the regions it serves; and 3) sustain future generations of Native communities through systemic change and intergenerational knowledge transfer. Weaving these three principles into a three-strand braid emphasized that each strand of the coalition’s work makes the others stronger, which aligned well with the BBBRC’s goals to ensure project-based investments were mutually reinforcing.

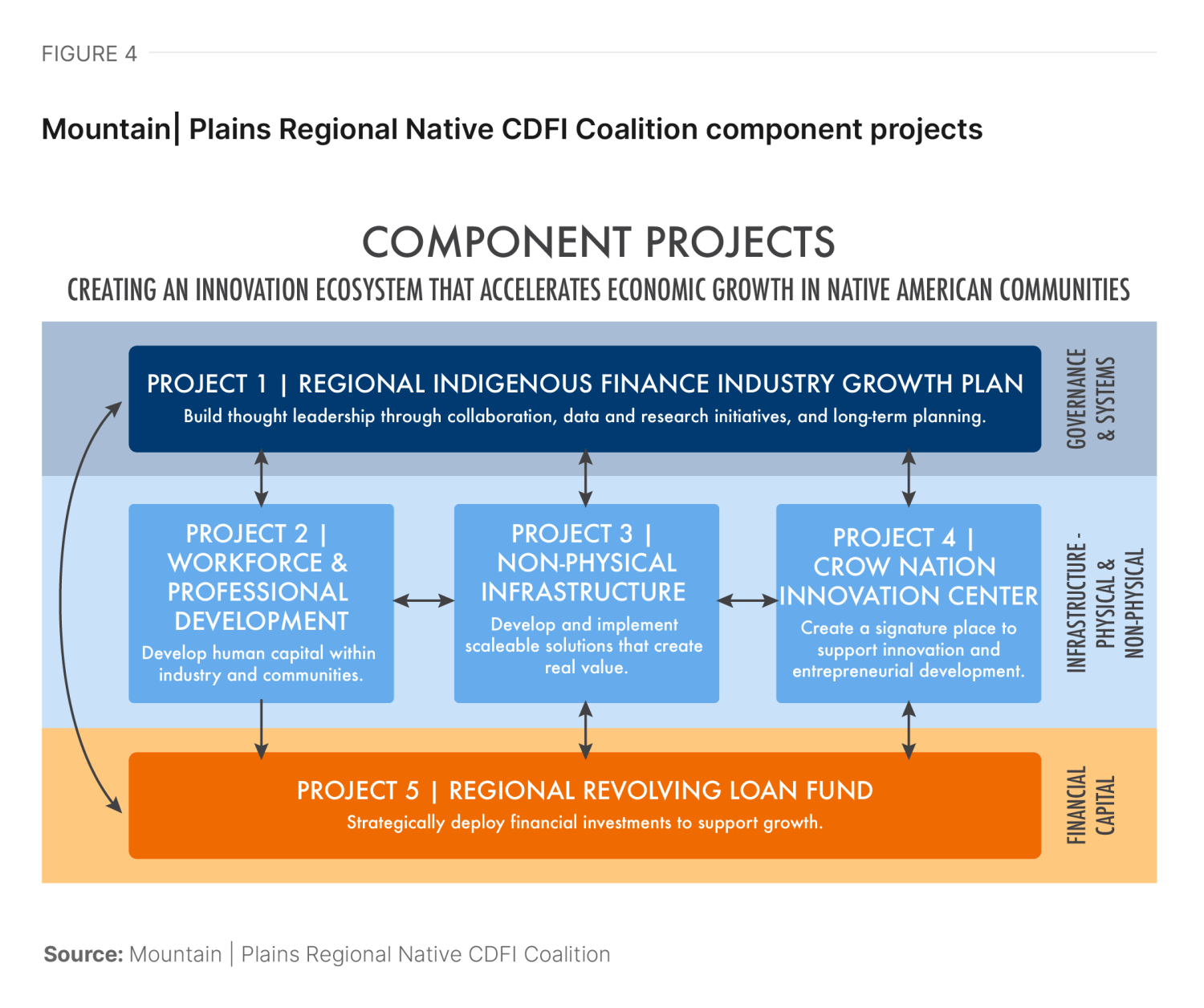

With that high-level vision in mind, the coalition set out to determine the critical investments needed to generate a viable Indigenous Finance Industry. The coalition identified three key themes that were needed for economic development in Native communities, under which they developed five projects. These themes are relevant for future coalitions looking to do similar economic development work in Indian Country:

- Governance and systems: Native communities must navigate a complex set of rules and jurisdictional relationships between tribes, federal agencies, state governments, and local municipalities. Meanwhile, a lack of data prevents tribes and community members from gaining a solid understanding of their baseline economic realities. To develop governance and systems, the coalition proposed as its first project to create a Regional Indigenous Finance Industry Growth Plan to build thought leadership, collect data for the coalition to use, conduct relevant research initiatives, support long-term planning, and build new approaches to power sharing.

- Physical and non-physical infrastructure: Many Native communities lack assets most Americans take for granted, such as a local tax base, building codes and zoning regulations, and adequate infrastructure such as clean water, roads, and sewers. Meanwhile, the social welfare of Native people has been marred by substandard, federally run health care and educational systems, as well as historical trauma. These barriers require specific investments to overcome in support of community and economic development. The coalition developed three projects to support the development of physical and non-physical infrastructure in the communities they serve. The coalition saw human capital as an essential piece of non-physical infrastructure, and so made their second project a Workforce and Professional Development effort to create a pipeline of qualified financial professionals from the Native communities the Mountain | Plains Coalition serves. The coalition’s third project centers on creating and scaling other forms of Non-Physical Infrastructure for use by the coalition, including a set of standards manuals and toolboxes, as well as a shared services platform to support coalition members with back-office services and procurement. The fourth project, focused on Physical Infrastructure, will construct up to two new buildings—a rarity in Indian Country, where muddled land tenure and complex federal rules can make new construction prohibitively difficult—as part of a Crow Innovation Center to house the Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation and create a new incubator space for entrepreneurs and small businesses.

- Financial capital: Many traditional financial institutions, which are constrained by inflexible underwriting standards, do not deploy capital on reservations. Others claim that complex jurisdictional matters between tribes and the federal government are deterrents. As such, coalitions must take steps to develop sources of capital that are willing to grapple with these perceived obstacles. The fifth project aims to grow the amount of financial capital flowing into Native communities in the region by creating a Regional Revolving Loan Fund (RLF) to capitalize the CDFIs involved in the coalition, and in turn deploy that capital to Native entrepreneurs and businesses. Because of the importance of finance and capital access to functioning economies, the RLF is a centerpiece connecting the Indigenous Finance Industry to broader economic growth for tribal economies. RLFs are designed to provide financing to borrowers who would otherwise be passed over by commercial lending, such as those who have limited credit history or are considered high risk. The aim of this new capital is to finance projects that many other communities take for granted, in turn accelerating growth for tribal economies and the region more broadly.

Since Phase 2 funding requests exceeded the BBBRC’s available resources, the EDA gave all Phase 2 finalists, including the Mountain | Plains Coalition, the opportunity to reduce their budgets. The coalition decided not to reduce their funding request, and was ultimately fully funded at their original requested amount of $45 million.

Receiving this crucial source of new federal funds was a tremendous accomplishment for the Mountain | Plains Coalition. The BBBRC grant is the single largest investment ever made into the Native CDFI industry—approximately four times the size of the average annual investment the Treasury Department’s CDFI Fund makes into all Native CDFIs nationally. But securing funds was not without its challenges. Exploring how the coalition overcome these challenges reveals what is necessary for place-based policies to be relevant to Indian County and other historically underinvested communities.

Determining the balance of funding from federal and non-federal sources—what is often called a non-federal funding “match”—was particularly important in the lead-up to the coalition’s submission. Cost sharing between the federal government and grantees is a common practice, since it helps federal dollars find additional financial leverage and ensures that recipients are contributing their own resources in service of the strategy. Yet resource endowments remain highly unequal across the country, with many smaller communities and rural areas facing unique challenges after being under-resourced for decades. This creates a difficult equilibrium, in that the very same regional inequities in access to resources that inspire place-based policies in the first place could prevent places from participating if they cannot offer competitive matching funds.

For the BBBRC, the non-federal financial match was a “competitive factor,” meaning it was considered by reviewers, but technically was not a requirement. In the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), the EDA wrote that applicants should expect the agency to fund at least 80% and up to 100% of eligible project costs, with the determination of increasing the federal share beyond 80% being considered on a case-by-case basis. Importantly for the Mountain | Plains context, the EDA indicated it would fund an investment rate of up to 100% for Indian tribes’ projects, and in “very limited other circumstances.” These details were important as Mountain | Plains put together its final application. Because Native CDFIs are nonprofit entities, not tribal government agencies, they were ineligible under the provision offering up to 100% support for tribes. While the EDA informed the coalition before the Phase 2 submission deadline that the 20% match was not a strict requirement, the coalition nonetheless perceived it would be at a competitive disadvantage if it was not secured.

In response, coalition members rallied to leverage the philanthropic and funding relationships they had developed over decades to secure matching fund commitments. In the 30 days before the BBBRC application deadline, the coalition was able to secure matching fund commitments equal to over 21% of their award total. Due to the relatively limited resources that the coalition had to work with (a function of serving some of the poorest communities in the U.S. while needing to navigate some of the highest barriers to capital access), securing these matching funds was a significant accomplishment for the coalition.

Subsequently, during implementation, the coalition worked with the EDA to obtain match waivers for their projects to free up unrestricted funding for more capital-intensive projects. After receiving its award, the coalition was able to work with the EDA to reduce their match funding from 20% to 7%. Freeing up 13% of its matching capital allowed the coalition to reallocate funding from less capital-intensive projects such as the Regional Indigenous Finance Industry Growth Plan into more capital-intensive ones such as the Crow Innovation Center. The coalition is now working with the EDA to further lower its match on two projects from 7% to 0% to increase more flexible and innovative use of match dollars.

The Mountain | Plains Coalition’s experience with the BBBRC reveals how important match funding is in determining access to competitive challenge grants, particularly for Native, rural, and underrepresented communities. Indeed, a recent Government Accountability Office report highlighted matching funds as one of the most significant barriers to tribes and Indigenous communities accessing competitive federal investments, such as those in the federal Justice40 environmental justice initiative. These lessons are applicable for all federal place-based investments that center equity as a stated objective.

The historical context matters as well. Given the United States’ history of harm to tribal communities, Native coalition leaders understandably expressed skepticism that federal policies could work for them. Federal officials that want their programs to be relevant for Indian Country must understand the systemic harm that the U.S. government has caused Native American people, as well as its responsibilities under trust and treaty obligations to tribes.

Given these considerations, place-based investments should lean toward greater generosity in match waivers if their goal is to prioritize equity. For its part, the EDA clearly recognized the unique burdens that Native American communities face, as it explicitly mentioned in the BBBRC NOFO its willingness to fund up to 100% of costs for Indian tribes’ projects. However, the coalition’s experience shows that limiting no-cost share criteria to only tribal governments was too narrow of a proxy for supporting Native communities. Broadening these provisions in future federal place-based grants to include certain Native-run or Native-serving nonprofit institutions, such as Native CDFIs, could mitigate some of the challenges that both the coalition and the EDA have faced during BBBRC implementation.

Embedding equity in the strategy

Through its composition and work, the Mountain | Plains Coalition exemplifies the EDA’s goals around equity. As the coalition’s application materials note, nearly 60% of their clients are women and over 95% are Native American, with an average household income of less than $34,000—below both the regional and national average. The work that the coalition is doing promotes equity by supporting entrepreneurs and businesses the mainstream finance industry passes over, whether because they are deemed “too risky,” are seen as having too few resources, or aren’t physically able to access a mainstream financial institution.

The coalition also reflects the EDA’s goals around equity in its own makeup. As Barbara Schmitt, executive director of Black Hills Community Loan Fund, noted, “We have 10 members, eight are strong Native American women.” Nine of the 10 partner organizations in the coalition are Native-led, and eight of the 10 are led by women. This aligns with the broader Indigenous Finance Industry. As the coalition noted in its BBBRC application narrative, women hold 72% of leadership positions at Native CDFIs, which is almost an inverse of the traditional finance industry, in which men hold 73% of leadership positions.

Equity is likewise core to the coalition’s project design. Through its holistic framework, the coalition ensured that its projects amplify strength, unify action, and sustain generations of Native communities. As such, the coalition underscores the EDA’s goals around equity in the communities it serves, the people it hires, and the activities it finances.

Implementing the strategy

The Mountain | Plains Regional Native CDFI Coalition was awarded a BBBRC grant in September 2022 and launched their programs later that year. This section tracks the coalition’s first year of implementation and identifies important early successes and challenges. The Mountain | Plains Coalition’s early implementation demonstrates to federal policymakers, finance industry practitioners, and state, local, and tribal leaders the elements needed to scale up financial services in communities that have historically been underinvested and underserved, including challenges and solutions for generating capital access and deal flow in a capital-scarce environment. It shows the important cultural considerations, including around historical trauma, that must be addressed to support economic development most effectively in Native and other underinvested communities. Finally, it illustrates some of the unique considerations that must take place for building productive capacity in Indian Country, particularly around workforce and physical infrastructure development.

Early implementation successes and challenges

- Operationalizing Indigenous-led governance and systems. Key to the growth of the Indigenous Finance Industry is building new narratives—both within Indian Country and to non-Native audiences—that combat the false stereotypes around the risks of Native markets and fuel excitement for the next generation of capital providers in Native communities.

To do this, the coalition first developed a governance structure based on Indigenous ways of working. The coalition is governed by consensus, with most major coalition decisions made by unanimous consent. This governance structure reflects how coalition members see themselves and their relationship to one another: as 10 co-equal partners. Each of the coalition’s five projects is housed within an individual coalition member, who is designated as the “project lead.” Project leads have responsibility over the day-to-day management of the project and ensuring project deadlines are met. Each project lead collaborates with two other coalition members on larger project-related decisions, such as those about unrestricted funds and funds whose uses are not fully defined or will have impact beyond a single project. This collaboration is referred to as a “triangle.”

One challenge that coalition members noted with implementing this governance model is that there can be ambiguity around who needs to be consulted to make a decision. While the coalition has delineated what decisions should be made at which level, in practice, it’s not always clear whether an individual decision should be made by a project lead, a triangle, or the entire coalition.

During implementation, coalition members have overcome this ambiguity by falling back on the deep interpersonal relationships they have developed with one another and shared norms of collaboration. Coalition members consistently emphasized that having an existing relationship before the BBBRC grant has helped them stick together through the inevitable misunderstandings. They also mentioned that because nine of the 10 coalition executive directors are Native American, they have a shared understanding around Indigenous ways of working. As Paul Huberty, executive director of Wind River Development Fund, said, “A unique aspect of the coalition is that we have a lot of respect for one another. Some of the executive directors may not even recognize the unique Native leadership structure of the coalition compared to other corporate organizations, because Indigenous values of humility and respect are ingrained in our work. It’s really genuine.”

In a focus group session, coalition staff members who were hired as part of the BBBRC effort expressed similar sentiments. They noted that despite being from different Native nations with distinct histories, they share a common history of colonization. As such, they were able to strengthen communication both within and across the different Native nations involved in the coalition, who at various points had been both allies and enemies. One staff member put it succinctly: “For Indian Country, that’s the way of the future: banding together.”

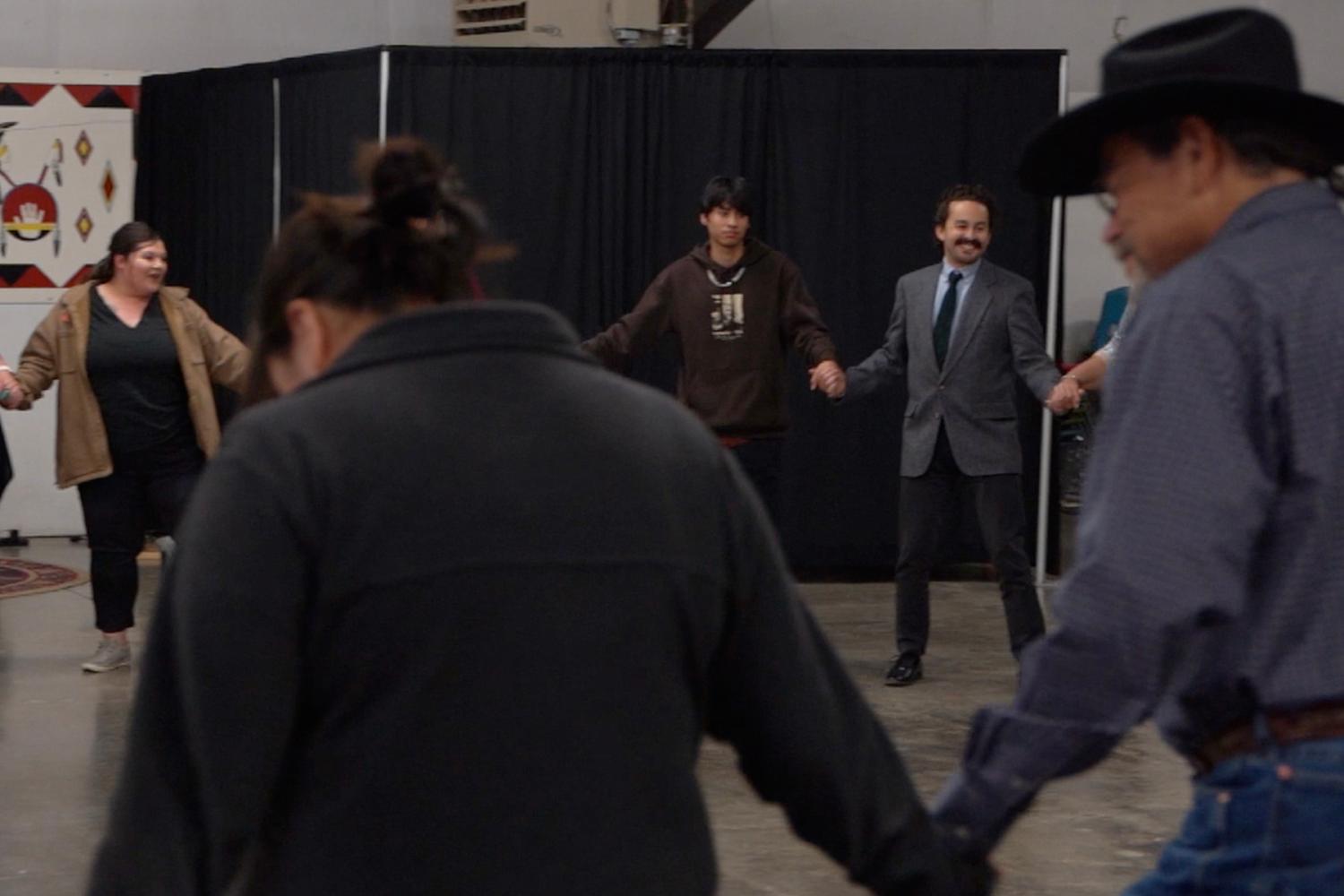

During implementation, the coalition’s Regional Indigenous Finance Industry Growth Plan project has taken a variety of steps to fortify the coalition’s governance processes and intellectual capital. These have included creating a values- and cultural-based letter of agreement between all members that aligns coalition governance with members’ shared, equitable values; hosting biannual convenings between the coalition and the region’s greater Indigenous finance ecosystem; training all coalition members in shared project management tools; creating a data framework that centers Native innovation as the coalition’s key performance indicator; and contributing analysis to all data collection efforts.

- Building non-physical and physical infrastructure to support the coalition and the communities it serves. Building the Indigenous Finance Industry requires significant investment in both non-physical infrastructure (e.g., a skilled workforce, business systems, etc.) and physical infrastructure (e.g., office space).

To start, the coalition is investing in its Non-Physical Infrastructure project, which will bolster its functioning and better enable its lending mission. An important goal for the coalition, and for similar mission lenders, is to generate scale, allowing coalition members to attract and deploy more capital.

The first ingredient the coalition needs to scale its mission and better support regional lending is a dedicated workforce. To do so, the coalition has been hiring rapidly. Since October 2022, coalition member CDFIs have experienced tremendous growth, onboarding 31 new staff to bring the total number of people involved in the coalition’s work from nine to 40.

These new hires have had important downstream industry- and community-level effects. In discussions with CDFI staff hired through the BBBRC process, they took pride in being part of the expansion of the Indigenous Finance Industry workforce. They were particularly proud of the peer-to-peer learning opportunities they’re developing across the coalition and with Native CDFIs across the country, which uplifts Native expertise as a norm for capacity-building. Coalition members also talked about how scaling up staff has helped more community members see firsthand the work that Native CDFIs are doing.

The coalition is enabling this hiring through its project focused on Workforce and Professional Development. Through that project, the coalition is developing a comprehensive plan to build the region’s pool of Native finance professionals. NACDC Financial Services, the project’s lead organization, is surveying coalition members to identify existing and potential future gaps in their internal capacity, and will support coalition members in filling those gaps over the next two to three years.

The coalition’s hiring experience has relevance for other coalitions and organizations operating in a mission-focused industry serving rural areas or distinct cultural communities. Coalition members noted there is a narrow segment of candidates that they can draw from. In addition to having the appropriate skills and background in the financial sector, candidates must also understand the Native CDFI mission and be passionate about supporting tribal economic development, which can often be harder to find. Coalition members have leaned into remote hiring and remote work to help source talent, but even with those options, it has still been difficult to find qualified and interested candidates. As one coalition member asked, “How do you find the right people in communities you’re not a part of?” Yet while building the pipeline of human capital and expertise has presented challenges, coalition members have had success in recruiting and training Native professionals from other industries such as education and social work, which they have found contributes to a more holistic approach to finance. Coalition members expressed excitement that their hiring would ripple out beyond the BBBRC grant period and facilitate permanent growth of the region’s Indigenous Finance Industry.

The workforce development that the coalition has undertaken as part of its BBBRC grant has also furthered its desire to create additional institutional partnerships to expand the industry’s human capital base. For example, the coalition is exploring the possibility of working with tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) in the region to create pathways for Native students into the Indigenous Finance Industry.

In addition to growing their workforce, the coalition is enabling scale by implementing a set of culturally relevant shared services for use by all coalition members through its Non-Physical Infrastructure project work. A significant early implementation win for this project was in March 2023, when the coalition created, stood up, and staffed an entirely new organization—the Mountain Plains Community Development Corporation (MPCDC)—to develop shared services for the coalition. This new organization is the first Native CDFI-designed and Native CDFI-serving shared services organization in the nation. After it was established, MPCDC was officially designated as the 10th coalition member.

One of the most significant challenges to scaling up this type of shared services organization was that the diversity of coalition members—spanning multiple geographies and markets, at different levels of maturity, and with varying products—created challenges for crafting services that provide benefit to all members. MPCDC has responded by building more general professional capacity such as legal services, allowing it to tailor individualized services to the specific needs of coalition members as they arise. MPCDC staff also emphasized the importance of having on-hand capacity to pursue outside opportunities that can bolster both MPCDC and the coalition’s overall capacity, such as attending events, building networks, pursuing funding opportunities, or recruiting promising personnel. Finally, MPCDC emphasized the importance of involving service recipients in the direction of the organization itself. For example, to ensure all the coalition members have a stake in MPCDC’s direction and success, the other nine coalition members all serve on its board of directors.

A final piece of learning from the coalition’s early implementation provides an example of the type of culturally sensitive support work that financial institutions, policymakers, and other entities aiming to support economic development in Indian Country and other underinvested communities must take on if they want to successfully enable growth. A centerpiece of the Workforce and Professional Development project has focused on trauma-informed lending, led by NACDC Financial Services and Black Hills Community Loan Fund. Within the Indigenous Finance Industry, CDFI staff frequently work with individuals who face financial trauma, or an intense and enduring emotional response to financial distress. Historic and ongoing circumstances that have created financial instability in Native communities generate systemic financial trauma for many Native people, who often feel personally responsible in a system that fails them. As a result, CDFI staff spend a significant amount of their time working with clients to improve their credit and support their ability to access financial resources.

People have a lot of shame and embarrassment about their financial situation. There’s shame and embarrassment because they’ve mismanaged their money. They get in trouble. We work to clear up their credit, but then they’re bombarded with credit cards. So we put something into place to support these community members, to counsel people. It all stems back to our historical trauma that everybody has experienced throughout their life, from seven generations back. Previous generations didn’t care about a credit report or a credit score. We used a barter system, so credit was irrelevant.

Angie Main, executive director, NACDC Financial Services

The coalition has created a resource directory to help members and staff who are working with trauma-affected clients, as well as an Indigenous finance money market training to help trauma-affected clients manage their finances more effectively. For its work on trauma-informed lending, NACDC Financial Services, in partnership with Black Hills Community Loan Fund, received a $100,000 Native CDFI Catalyst Award from the Opportunity Finance Network in October 2023, which will allow CDFIs throughout the country to implement the approach that the two organizations have created.

To develop Physical Infrastructure project work, the coalition is leveraging the Crow Innovation Center on the Crow Indian Reservation as a pilot to gather best practices for constructing buildings within tribal nations in the region. The coalition’s experience with developing this new physical infrastructure holds important lessons for policymakers as well as philanthropic and private sector partners interested in supporting community-driven economic development on tribal land.

Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation, the lead CDFI on the project, is constructing a multi-use building on one of two adjacent lots in Crow Agency, which will be used to incubate businesses and provide office and training space, and will include a marketplace for community members, a commercial kitchen, and vendor areas. Constructing the innovation center will be a four-year project. In the short term, Plenty Doors has purchased an existing building to operate as a temporary incubator. There are three businesses and one nonprofit currently incubated in the space, which has doubled the number of Native-owned businesses with a physical presence in the town of Crow Agency. Plenty Doors has also been selected as a finalist for the EDA’s Recompete Pilot Program. If awarded those funds, they will build a second building on the adjacent lot. Once the building is completed, three other CDFIs in the coalition will receive EDA funds to become “shovel ready” for physical infrastructure projects and begin to adapt and contribute to best practices.

There are a variety of obstacles that make it extraordinarily difficult to undertake new construction on rural reservation land, which is an important consideration for those aiming to support physical redevelopment in Indian Country. A significant one is that many tribes, including the Crow Nation, operate without a tax base, which makes it difficult to fund public infrastructure projects such as power, water, roads, and sewers. Similarly, many reservation communities, including Crow Agency, don’t have building codes, which meant the coalition has needed to hire private reviewers and inspectors, driving up costs. Furthermore, there is only one contractor on the reservation, and non-reservation contractors often charge a premium to work on tribal land, increasing development costs further. There are also relatively few construction workers on the reservation. As Plenty Doors navigates this process, it is working with fellow coalition member Akiptan, which is leading the documentation effort and will be one of the other CDFIs that will be ready for construction. In addition to its close work with Plenty Doors, Akiptan is also interviewing other CDFIs that have a successful history with buildings, such as NACDC Financial Services and Four Bands.

These construction issues raised questions about the best method for the Mountain | Plains Coalition to be awarded funds to avoid cash flow issues, which can be particularly acute in construction projects because of the scale of output and nature of construction invoicing. For the typical EDA-funded project, the agency provides payment on a “reimbursement basis,” which means that coalitions are compensated after costs have been incurred. For construction projects, the EDA made clear that advance payments could be granted in “rare and compelling circumstances.” Providing advance payments would ensure that contractor invoices do not exceed the cash on-hand of less resourced coalitions. However, under federal payment rules, those advance payments also require more administrative steps than reimbursements. During the startup phase of the grant, the coalition worked in a mutual relationship with the EDA to determine which payment method to use. In the end, although the coalition had the option for advance payment under federal payment rules, both parties agreed that they would create more administrative burden than reimbursements. Given that, the EDA and the coalition decided to work closely together to streamline reimbursement to the best of their mutual ability.

Coalition members noted that their experience working with the EDA around reimbursement could serve as a learning experience for other federal agencies looking to invest in Indian Country. Coalition members also highlighted the opportunity for the Commerce Department to learn from other federal departments, such as Treasury and Agriculture, that have extensive experience making payments to entities in Indian Country. They emphasized that the BBBRC—and the current moment of place-based investment more broadly—could become a prime opportunity to generate more cross-agency sharing of best practices for investing in Indian Country.

Because they are operating on a reimbursement basis, the coalition has faced challenges around cash flow. Some coalition members discussed needing to divert dollars away from other core business operations, including lending, to fund BBBRC project work. Such cash flow challenges are another factor that could dissuade coalitions in capital-constrained regions from applying for transformative federal grants.

In response, through its work in Project 3, MPCDC has taken steps to secure cash flow for coalition members, which can serve as an example of how similarly under-resourced coalitions can navigate challenges with federal payment rules. Having identified early on that Native-led entities are forced to operate in an environment of systematically low levels of working capital (which federal payment rules exacerbate), MPCDC secured $1.7 million over two years from Wells Fargo’s Invest Native initiative to provide short-term loans to coalition members. This funding is helping the coalition continue deal flow in the region—which was documented to be over $15 million in spring 2024—while navigating cash flow concerns that have come from the federal payment model.

- Deploying financial capital to Native borrowers and communities. Capital access is essential for economic development, but as discussed above, remains in short supply in many rural Native communities. The coalition’s experience establishing its revolving loan fund provides important lessons on the level of financial assets needed to create transformative economic change, best practices for knowledge sharing across financial institutions, as well as some of the challenges that come from leveraging federal funding in capital-scarce environments.

Over half of the coalition’s EDA award is devoted to a $22 million Regional Revolving Loan Fund (RLF) stewarded by Four Bands Community Fund. The RLF is central to the strategy because it afforded the coalition a large amount of seed capital required to lend at greater scale. Indeed, the Mountain | Plains Coalition is the recipient of the second largest RLF award and the largest regional (i.e., multi-state) RLF award in the EDA’s history. The coalition’s RLF experience, therefore, has important takeaways for developing knowledge sharing and lending capacity across financial institutions, particularly those operating on tribal land and in capital-scarce environments.

Building the largest regional RLF in EDA history—as well as the largest investment into the Native CDFI industry—took a significant amount of time and effort. The RLF’s ambitious design was a positive because it is now enabling unprecedented funding to flow to some of the communities most in need. However, the size and scope of the RLF also brought complexities. For example, the EDA has an array of requirements to ensure awardees have laid out steps to utilize the funds. While these requirements are standard EDA procedure, they were time-intensive for the coalition, and complicated by the fact that the RLF would be operating in multiple states. Additionally, factors unique to Indian Country meant that the EDA and the coalition needed to engage in multiple rounds of revisions to the RLF plan. For example, the EDA had to learn how to design an RLF that could incorporate products that Native CDFIs offer, such as collateralizing trust land. Coalition members at various points expressed frustration at the length of time the RLF negotiations took given the urgent capital access needs in their region. But while this process was difficult, it also created opportunities for mutual learning, and enabled the EDA to refine its RLF process in anticipation of future Native and regional funds.

The coalition has leveraged its advocacy work in Project 1 to help the EDA evolve its RLF process to make it more accessible and impactful for Native-led organizations. Changes the EDA implemented include:

- Identifying a straightforward process to allow EDA RLF grantees to refinance existing loans. This is particularly critical in reservation economies, where many Native borrowers are saddled with high-interest loans due to the lack of financial institutions. This change will help Native American borrowers with existing debts unlock new financial opportunities by being able to access more reasonable borrowing.

- Creating single-year payments for agricultural loans within the RLF. The standard monthly repayment schedule used for RLF funds doesn’t work well for agricultural lending (a substantial segment of rural and Native American lending), because many agricultural businesses make all their money once per year when they sell their products. The coalition was able to work with the EDA to allow for once-a-year repayment for certain RLF-funded agricultural loans, which will help future Native, rural, and agricultural lenders and borrowers.

Coalition members expressed pride in the changes they were able to work with the EDA to enact, particularly around knowing that future Native CDFIs and tribal communities would be able to benefit from the changes. As Skya Ducheneaux, executive director of Akiptan, said, “All of that was time that could have been spent doing something else, but for the next person it will be a 30-minute process.” The EDA shared this sense of pride, seeing the RLF as reflective of the relationship-based approach they worked to cultivate with the coalition.

Since its launch, coalition members emphasized that the RLF has enabled valuable peer-to-peer learning among participating lenders, who have varying degrees of experience. The RLF process has created an opportunity for the newer lenders to be in the same room as some of the coalition’s more established ones, allowing them to learn firsthand from some of the most sophisticated lenders in the Indigenous Finance Industry.

One outstanding policy challenge coalition members noted is that for the first seven years of the RLF, funds can only be reinvested back into the RLF. They noted that this provision limits their ability to use their financial returns for other uses, such as growing partnerships with other financial institutions like banks, which may in turn harm their ability to scale. This requirement is set by congressional statute, and coalition members highlighted it as a policy in need of change.

Tracking implementation and outcomes through metrics

In its application materials to the EDA, the coalition emphasized the importance of data for Native communities. As the coalition noted in its application materials, in a review of 30 articles on the racial wealth gap, 23 (77%) either excluded Native Americans entirely or included them only as an asterisk indicating sample sizes were too small to be significant. The systemic exclusion of Native people and nations from economic data has led to what the National Congress of American Indians calls the “Asterisk Nation” problem. Given this important context, developing capacity around data and metrics is a top priority for the coalition.

As CDFIs, coalition members already track a significant number of metrics, with a particular focus on capital deployment in the communities they serve. As financial institutions with a community development focus, coalition members are prioritizing building further capacity to track community- development-oriented metrics through their project work.

Through the coalition’s Regional Indigenous Finance Industry Growth Plan, led by Four Bands Community Fund, the coalition is implementing a regional data collection and reporting effort that will detail the BBBRC’s impact on the broader economy in the Mountain-Plains region. As part of this effort, the coalition is planning to publish two regional data projects during the five-year BBBRC implementation process, with the aim of dispelling misconceptions about Native economies in the Mountain-Plains region through data. These efforts are being complemented by the coalition’s Non-Physical Infrastructure project, which supports building regional capacity for consistent data collection through the customization of Salesforce as an IT solution across the region.

The Mountain | Plains Coalition has also been participating in a metrics collection effort led by Purdue University that is measuring the impact of the BBBRC’s projects on regional economies. Coalition members said they could see the value in the metrics Purdue is collecting, and hoped to leverage them in the future to tell the story around the coalition’s impact on the Native nations and regions that it serves. However, one concern coalition members expressed about efforts like Purdue’s is that metrics collection and reporting processes require significant capacity around data collection and analysis. Coalition members noted that capacity may not exist in less resourced organizations operating in Indian Country. Indeed, coalition members noted that even within the coalition itself, metrics and data collection capacity varied, which is why Projects 1 and 3 of their award are designed to build that capacity. While some coalition members such as Four Bands and NACDC Financial Services are national leaders in leveraging metrics and data to support their businesses and the Indigenous Finance Industry, others felt at times that they were expected to already be able to do the type of work that the EDA was funding them to develop.

The coalition also identified an array of compliance-related metrics and related federal policies that they felt made it more difficult for Native-serving financial institutions to implement this type of large-scale federal funding opportunity, such as revenue tracking requirements, interest accrual reporting, and the need to use a request-for-proposal process to make sub-awards.

Finally, coalition members expressed an interest in measuring their impact beyond standard economic development measures such as job creation. Coalition members named Native innovation—or the products and processes developed through Indigenous knowledge to meet the needs of clients and communities—as a key performance indicator. During interviews, coalition members noted a variety of items that they felt could help measure the community and economic development impacts of Native innovation, including:

- Community wealth development and redistribution, including first-time access to credit

- Intergenerational wealth creation and healing financial trauma across Native economies in the region

- Growth of CDFI leadership confidence in the region

- Changes to tribal economic systems in areas such as industrial development and the reduction of economic leakage

- Increased utilization of trust land across the region because of the work of Native CDFIs

Above all, coalition members expressed that metrics collection and publication should focus on narrative and systems change. In this regard, they emphasized that metrics must not only tell a story of economic transformation, but also help dispel the ongoing harmful stereotypes of Native nations and tribal economies. This type of asset-based storytelling is central to all the coalition’s work on metrics, and should be a core focus of ongoing and future federal economic investments in Indian Country.

The coalition’s work has also informed change elsewhere in the Commerce Department and federal government. For example, the coalition’s work informed the creation of the Census Bureau’s the Opportunity Project (TOP) sprint focused on improving access to capital in Indigenous communities through data—the first-ever Indigenous-focused TOP sprint. After the completion of the sprint, the Census Bureau announced that they plan to hold at least one Indigenous-focused TOP sprint every year moving forward.

Implications

The experience of the Mountain | Plains Coalition provides lessons for multiple groups: for other Native-led organizations interested in accessing large federal grants, for underinvested communities that are assembling coalitions and applying for federal funding, and for federal agencies investing in capital-scarce communities, including those in Indian Country.

What follows are four topline takeaways from the experience of the Mountain | Plains Coalition:

- Federal agencies must recognize that Native-led institutions have distinct perspectives on the role of federal grant programs in bolstering economic development in Indian Country, and support them accordingly.

Given the specific role that federal policy has historically played in creating the economic conditions facing Native communities today, coalition members expressed the importance of ensuring that the burden of policy change falls more equally between the federal government and Native people, rather than leaving it primarily to Native people to seek change. This sentiment has been echoed by other Native-led organizations. For example, the United Southern and Eastern Tribes has written that due to the debt that the U.S. government owes to Native nations for taking their land and resources, “all actors within the federal government must consistently protect the interests of all Tribal Nations in every policy and action they undertake.”

Native entities often see federal investment, including place-based challenge grants, as a broader extension of the trust and treaty obligations that the federal government owes to tribes. Indeed, place-based economic development strategies align with the very definition of Indigeneity, which is based on a people’s relationship to a place since time immemorial. As such, place-based strategies are a potentially powerful way to uphold treaty responsibilities. Given these considerations, the federal government has an obligation to make place-based funding as open, accessible, and implementable as possible for Native-led entities. Federal agencies should be aware of this difference in perspective when working with Native-led and Native-serving coalitions.

- The Mountain | Plains Coalition illustrated that large place-based policies can deliver scaled investment in Indian Country, but doing so greatly tested the adaptability and resilience of the coalition and the EDA.

The coalition’s decision to apply for the BBBRC rather than smaller, tribally oriented federal funding streams was significant. Many coalitions in capital-scarce communities, including many Native-led coalitions, may not have seen a large, place-based federal investment like the BBBRC as a viable option for them.

Entities serving capital-scarce communities can often be reluctant to apply to transformative public grants because of the low chances of winning and the capacity requirements that are needed to implement them. Those factors were at play for the Mountain | Plains Coalition, just as they were for other applicants from capital-scarce communities. Just 21 coalitions won BBBRC awards out of a total of 529 applicants (a success rate of less than 4%). Likewise, in a nation where less than 0.5% of philanthropic funding explicitly benefits Native Americans, the EDA’s $45 million BBBRC award is the largest single investment into the Indigenous Finance industry in history. For many applicants from capital-scarce communities, smaller federal investments that offer greater chances of success and require less scale-up in capacity to implement would have felt like the safer decision. This dynamic is critical for federal agencies to keep in mind as they design and implement future place-based federal investments.

Implementing such a relatively large investment has also exposed differences in views between the coalition and the federal government. Coalition members give credit to the EDA for their willingness to work hard and be flexible around updating policies and procedures that were ill-fitting for Indian Country. Coalition members feel that their experience in advocating for the EDA to make the BBBRC program work better for Indigenous communities proves that when federal agencies are responsive to the unique conditions in Indian Country, the needle starts to move.

- Equitable economic development requires investment into coalitions led by historically underinvested populations, including communities of color.

Coalition members emphasized to Brookings that many of the economic inequalities they aimed to address through their work, such as the racial wealth gap, are the result of historic and ongoing U.S. policy decisions, and that putting historically underinvested organizations into positions of power and decisionmaking is key to solving those challenges. As Jael Kampfe, of Indigenous Impact Co., the firm serving as the coalition’s regional economic competitiveness officer, said, “Representation through leadership matters. Redistributing power is an essential precursor to redistribution of wealth.”

To the extent that policymakers want to promote economic justice, it is important that coalitions not only incorporate underinvested communities, but be led by them. Putting money directly into the hands of historically underinvested communities, including communities of color, and allowing them to make their own decisions on how to invest in themselves is one of the most important elements in facilitating real community and economic development. When community members feel like programs or investments are being made “to them” and not “with them” or “by them,” they may deem them nonviable from the beginning. To that end, as the federal government undertakes future large-scale challenge grants, it will be important to invest in coalitions led by organizations from underinvested communities—including Indian Country.

The experience of the Mountain | Plains Coalition offers specific instances of why representative leadership also matters for strategic efficacy. Investing in a Native-led coalition was fundamental because Native CDFIs had trust and relationships with borrowers, which meant they had a ready-made pipeline for deal flow. They could deliver better products and services to those borrowers, such as culturally competent, relationship-based, and trauma-informed lending. And because of their leadership, coalition members had a unique level of commitment to work through the hard issues of delivering those products and services in a challenging business environment, unlike any other market actor. It would have been nearly impossible for a national non-Native CDFI provider or a bank without these preexisting assets to successfully build an Indigenous finance cluster.

- The Mountain | Plains Coalition’s 10-member CDFI and CDC network offers a model for how relationship-based community finance can help build more inclusive regional economies.

Finally, the experience of the Mountain | Plains Coalition demonstrates the ingredients needed to seed community finance models that stretch across multiple communities and states—particularly in rural and capital-scarce regions.

During this case study, coalition members consistently emphasized that the coalition is able to stick together and maintain healthy working relationships because of the executive directors’ long histories of working with one another, which has fostered a sense of trust. That trust has allowed coalition members to feel comfortable disagreeing where necessary, as well as safe in the knowledge that other coalition members have their best interests at heart.

This trust and these healthy working relationships are further bolstered by the shared perspective that many coalition members have as Indigenous people, as well as the coalition-wide commitment to Indigenous ways of working. The coalition’s emphasis on Indigenous values of collaboration and consensus can only work with full buy-in from the entire coalition.

This approach draws from coalition members’ experience with relationships being central to their mission. As mission lenders serving some of the least capitalized communities in the United States, coalition members have long relied on relationship-based strategies to shape their lending practices, helping grow both their communities and the Indigenous Finance Industry. Coalition members expect their partners to also adopt this relationship-based approach, whether as colleagues within the coalition itself or partners within the broader Indigenous Finance Industry ecosystem (such as funders).

Coalition members also credit a relationship-based approach for their ability to work with the EDA to achieve needed policy and practice changes, as well as to hold the agency to a new standard around what values it brought into Native spaces. This type of relationship-based approach is critical for entities looking to scale truly inclusive economic development in communities that have been historically underserved and underinvested.

Conclusion

Moving forward, it’s critical that the U.S. federal government acknowledge and recenter the responsibility that it holds for creating the economic conditions under which the coalition is operating. Those with power—in this case, the U.S. federal government—created the circumstances that have long impaired Native economies, and thus hold greater responsibility for the solutions. However, historically it has been those living with the impacts of these actions that have driven change. In other words, the burden has been on Native people to advocate for changing harmful federal policies, rather than on the U.S. government to proactively change its own policies. That dynamic must change.

In awarding the Mountain | Plains Coalition a BBBRC grant, the EDA is contributing to changing that dynamic. To sustain and scale this change, federal agencies should take three actions. First, large, place-based economic investments, such as those the EDA provided through the BBBRC, must continue to be made as accessible as possible to Native communities and other historically underinvested communities. Historically, Native communities have been among the most overlooked by federal policy, and place-based investments can help break that cycle. The EDA’s support for underinvested communities, including Indian Country, must be complemented and scaled by other federal agencies, and those agencies can learn from the EDA’s approach to ensure their programs are accessible.

Second, federal agencies must continue to emphasize relationship-based strategies for program implementation, as the EDA has done during BBBRC implementation. For centuries, federal policy was not designed to support economic development in Indian Country, but to suppress it. Agencies must act as partners with Native grantees to deliberately reshape their program requirements and implementation to meet the unique situation and constraints that Native communities and Native-serving entities face.

And third, investments must be sustained over time. The Native nations of the Mountain-Plains region have been undergoing U.S. colonization for nearly 200 years. It will take much longer than just the BBBRC’s five-year grant period to reverse the impacts of that colonization. However, with sustained, long-term financial commitment by the federal government, complemented by greater investment from philanthropy and the private sector, there holds the promise for durable change for Indigenous people in the Mountain-Plains region—and Indian Country as a whole.

EDA case study series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Acknowledgements

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publications are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or other scholars.

Brookings recognizes the value it provides in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its funders reflect this commitment.

The authors thank Alex Jones, Bernadette Grafton, Ilana Valinsky, Ryan Zamarripa, Rachael Sun, Patrick Waggoner, Ashley Zuelke, Suyog Padgaonkar, Scott Andes, and Justin Tooley from the Economic Development Administration for their insights into the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and for their guidance throughout the development of this case study. For their comments and advice on drafts of this paper, the authors also thank our colleagues Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, and Mayu Takeuchi, as well Jael Kampfe, Gerald Sherman, Kayla Gray, Naatosi Fish (Indigenous Impact Co.), Lakota Vogel, Shalyn Hawley, Tommy Robinson (Four Bands Community Fund), Eric Swack (Mountain Plains Community Development Corporation), Barbara Schmitt (Black Hills Community Loan Fund), Angie Main, Leona Antoine (NACDC Financial Services), Paul Huberty (Wind River Development Fund), Skya Ducheneaux, Justine Kougl (Akiptan), Sue Taylor (Native American Development Corporation), Kerry Shabi (Montana Native Growth Fund), and Charlene Johnson (Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation). The authors also thank Jo Ann Eder, Sara Urbanik (O.P. and W.E. Edwards Foundation), Christianne Lind, Karla Miller, Nikki Foster, Paul Bachleitner (Northwest Area Foundation), and all local leaders, community-based organizations, economic development practitioners, regional intermediaries, higher education institutions, industry representatives, and other coalition members who participated in informational interviews and site visits throughout this project, and who provided feedback on the research insights and policy recommendations detailed in this report.

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

About Brookings Metro

Brookings Metro collaborates with local leaders to transform original research insights into policy and practical solutions that scale nationally, serving more communities. Our affirmative vision is one in which every community in our nation can be prosperous, just, and resilient, no matter its starting point. To learn more, visit www.brookings.edu/metro.

-

Footnotes

- Economic Development Administration. “FY 2021 American Rescue Plan Act Build Back Better Regional Challenge Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (ARPA BBBRC NOFO).” U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better

- Ibid.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).