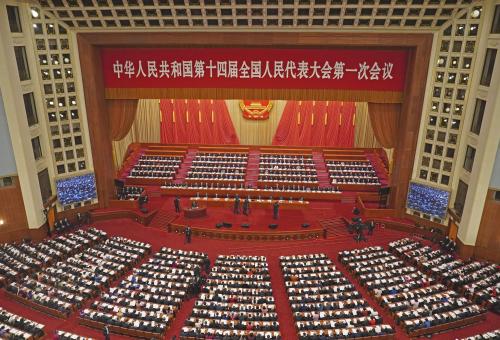

Chinese leader Xi Jinping plans to visit Moscow for his 40th face-to-face meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin. This visit will occur roughly one year after Russia invaded Ukraine and against the backdrop of reports that China is considering providing lethal assistance to Russia’s military.

Over the past year, China has expanded trade links with Russia and amplified Russian propaganda. Chinese authorities have defended Russia’s actions and accused NATO and the West of fomenting war in Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, American and European public opinion of China has plummeted. China’s embrace of Russia throughout its invasion of Ukraine certainly contributed to this trend.

Even so, as Xi’s upcoming visit makes clear, Beijing remains firmly committed to growing its relationship with Moscow. Some ascribe this orientation to Xi’s strong personal bond with Putin. This may play a small role. Xi has, after all, described Putin as his “best friend.” Even so, in my personal experiences around Xi and my study of his leadership over the past decade, Xi has proven himself to be uniquely unsentimental. He is a cold-blooded calculator of his and his country’s interests above all else.

China’s three goals

China’s leaders appear guided by three top objectives in their approach to Russia. The first is to lock Russia in for the long term as China’s junior partner. Of course, Chinese officials are careful to avoid referring to Russia as such. Instead, they treat Putin with pomp and deference. Xi flatters Putin in ways he does not any other world leader.

It is worth recalling that Xi is old enough to remember when Sino-Russian relations were fraught and the risk of a Sino-Soviet nuclear exchange was real. The two countries fought a border conflict in 1969, when Xi turned 16. During Xi’s formative years, the Soviet Union maintained a massive military presence along the Sino-Soviet border, deploying up to 36 divisions.

For Xi, cementing Russia as China’s junior partner is fundamental to his vision of national rejuvenation. China views the United States as the principal obstacle to its rise. Having to focus on securing its land border with Russia would divert resources and attention from China’s maritime periphery, where Xi feels the most acute threats.

Xi likely also sees the benefit of Russia distracting America’s strategic focus away from China. Neither Beijing nor Moscow can deal with the United States and its partners on its own; they both would rather stand together to deal with external pressure than face it alone. Given China’s dependence on imports for food and fuel, Xi likely also values the secure and discounted supplies of these critical inputs that Russia provides.

China will remain committed to navigating Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in a manner that keeps Russia as its junior partner. Seen through this lens, China’s amplification of Russian propaganda, its continuous diplomatic engagement, its ongoing military exercises, and its expanding trade with Russia all are supportive of its broader objective.

Russia’s strategic value to China requires that Moscow not objectively lose in Ukraine, though. Thus, China’s second objective is to guard against Russia failing and Putin falling.

China has been judicious in its support for Russia over the past year. It reportedly has refrained from providing lethal support to Russia, largely out of self-preservation and self-interest. China has, however, picked up significant slack in its commercial engagement with Russia. As Russia’s trade with the developed world has plummeted, China has stepped in to fill the gap. China-Russia trade exceeded a record-breaking $180 billion last year (roughly one-quarter of the volume of U.S.-China trade).

China’s third objective is to try to de-link Ukraine from Taiwan. Chinese leaders grate at the suggestion that Ukraine today foreshadows Taiwan tomorrow. They want the world to accept that Ukraine is a sovereign state and Taiwan is not, and that the two should not be compared.

This goal informed China’s peace proposal for Ukraine. Chinese diplomats almost certainly will seek to chip away at Ukraine-Taiwan comparisons going forward. In addition to chafing at the increased international attention being devoted to Taiwan’s security, China’s leaders do not want the developed world to treat its response to Russia’s aggression as a warmup for how it would react to future Chinese actions against Taiwan.

The siren call of equating China with Russia

Faced with these Chinese objectives, many American, European, and Asian policymakers might reasonably conclude that there is no prospect for dissolving the Sino-Russian entente, so they should seek instead to frame China and Russia as two sides of the same coin. According to this logic, doing so could cause China to pay as high of a reputational price as possible for being an accomplice to Russia’s barbarism in Ukraine.

This approach will be enticing for policymakers who are focused on forging tighter alignment with partners on China. They will want to leverage Beijing’s diplomatic tilt toward Russia to accelerate alliance coordination in countering China.

There are three main problems with such an approach, though. The first is that focusing on driving up reputational costs on China is insensitive to the suffering of Ukrainians who are struggling to survive Russia’s onslaught. No Ukrainians’ lives will be improved by worsening public perceptions of China.

The second is the risk of creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. If unlimited Chinese support for Russia already is priced in and Beijing risks no further costs for expanding its support for Moscow, then there is a higher likelihood of this becoming a reality.

This leads to the third problem — there are still meaningful things Russia is withholding from China that it conceivably could give if the relationship truly moves toward a “no-limits” partnership. These include Russian support for a greater Chinese role in the Arctic, Russian permission for Chinese forces to access its constellation of bases around the world, Russian support for China’s submarine and anti-submarine warfare programs, and deeper and more directed global intelligence cooperation.

Rather than resign to fatalism about the impotence of diplomacy to influence Chinese strategic choices, now is a moment for world leaders to stimulate Chinese thinking about the significance of the choices they are confronting. Similar efforts over the past year have had some effect. For example, at the urging of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and others, Xi exhorted against the threat or use of nuclear weapons. China has thus far refrained from proving lethal assistance to Russia. Beijing has not recognized the breakaway republics in Ukraine.

Focus areas for diplomacy

Looking forward, there are two baskets of issues where the United States and its partners should think carefully about how to most effectively protect their interests in relation to China, Russia, and Ukraine.

The first is tactical. Xi reportedly plans to call Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy following his visit to Moscow. It would be wise for American and European policymakers to follow Zelenskyy’s lead in determining how to characterize and respond to Xi’s outreach. There likely will be a strong impulse in many Western capitals to dismiss Xi’s effort as symbolic posturing aimed at airbrushing China’s image.

China clearly is partisan in its support for Russia. Beijing is not a credible fulcrum for any peace process, though it is conceivable that China could play a role as part of a signing/guaranteeing group for any eventual peace deal. Even so, there is little to be gained by repeating the stampede to dismiss Xi’s outreach to Zelenskyy in the same way that many Western capitals discounted China’s peace plan. The Ukrainians are sober to the scale of the reconstruction bill that awaits them at the end of the fighting. They will both want and need Chinese contributions. As such, it would be best not to open space between Zelenskyy and other Western leaders on how Ukraine should engage China on the way forward.

Second, at a more strategic level, now is a critical moment for global leaders to challenge Xi to clarify China’s interests on the future of the war in Ukraine. For example, will China exercise its leverage to encourage off-ramps and oppose further escalation? Will China condemn attacks on civilians? Will China support future investigations to hold perpetrators of atrocities in Ukraine to account? Will China continue to oppose all threats or uses of nuclear weapons? Will China continue to refrain from recognizing breakaway republics? Will China contribute resources now to lessen the suffering of Ukrainian refugees? Will China commit to materially support Ukraine’s reconstruction?

Now is not the time to give up on diplomacy

There are important opportunities on the horizon for world leaders to coordinate efforts to push Xi to clarify China’s intentions on these and related questions. They include the upcoming planned visits to China of French President Emmanuel Macron and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, a possible upcoming visit by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, an expected phone call between U.S. President Joe Biden and Xi, planning for the China-EU Summit, and Xi’s participation in the G-20 leaders meeting in India in September. The more coordinated world leaders are in pressing Xi to clarify where China stands on some of these fundamental questions, the more impactful such communication would be.

Ultimately, Beijing will not disavow Moscow. Even so, there are still boundaries that can be preserved and Chinese contributions that could be secured to relieve suffering and improve Ukraine’s prospects. It also is imperative to preserve trans-Atlantic unity and limit opportunities for China to drive wedges. None of this would ameliorate deep misgivings about Chinese conduct at home or abroad, but in the world of diplomacy, it would count as progress.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Fatalism is not an option for addressing China-Russia relations

March 17, 2023