The one-minute version of this case study

- The South Kansas region’s aerospace cluster is simultaneously facing growing demand and acute challenges. Known as the “Air Capital of the World,” the South Kansas region will be central to nation’s ability to meet rising global aerospace demand. Industry experts forecast the need for 40,000 additional commercial aircraft in the next two decades—almost twice as many as are in the air today. Yet South Kansas faces challenges in meeting this demand—specifically, the grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX in 2019 and the pandemic-induced decline in air travel, which cost the region an estimated 25,000 jobs.

- The region’s core challenge—and opportunity—is building a resilient, diversified advanced manufacturing cluster. With over 30,000 workers, the region’s employment concentration in aerospace manufacturing is 33 times higher than the U.S. overall. But the recent shocks outlined above have underscored the need for the region to diversify into other sectors, both within and beyond aerospace. To do this, the region’s 450 suppliers need to upgrade their innovation capabilities to meet the demands of a new industrial era. Amid a historically tight labor market, adopting leading-edge technologies can help those suppliers remain competitive, but it will require preparing an increasingly diverse talent base with the technical skills needed for that adoption.

- The Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) is bolstering South Kansas’ position as a world leader in additive and smart manufacturing. The South Kansas Coalition’s $51 million BBBRC strategy is a story of a region leveraging its highly concentrated aerospace industry and other advanced manufacturing assets to become an international leader in additive and smart manufacturing. Through the BBBRC, an engaged set of university, civic, and industry leaders is investing in the technologies and talent programs required to prepare a diverse swath of workers and companies to drive a more inclusive form of economic growth.

- Regional universities can be critical anchors for cluster development and innovation. This case study explores Wichita State University’s vital role in the design and implementation of the South Kansas Coalition’s advanced manufacturing cluster initiatives, including support and trainings for small and medium-sized manufacturers, the construction of a new applied research training facility, and inclusive talent pipeline development. It offers lessons about the key role that regional public universities can play—with the appropriate resources—to coordinate and drive a range of economic development functions spanning research, commercialization, firm attraction, and workforce development.

Before reading this case study: What is the Build Back Better Regional Challenge?

This brief overview of the program provides useful context before reading this case study.

In July 2021, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) launched the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) through a Notice of Funding Opportunity that outlined a two-phase competition.1 Through its Phase 1 activities, the EDA issued an open call for concept proposals that outlined a high-level vision for a “transformational economic development strategy.” The thesis was that regions would identify an industry cluster opportunity; design “3-8 tightly aligned projects” to support that cluster; build a coalition to “integrate cluster development efforts across a diverse array of communities and stakeholders”; and ensure that these collective efforts advance equity by supporting economically disadvantaged communities.2

In Phase 1, 529 coalitions submitted high-level concept proposals that outlined a vision for the cluster, a high-level description of potential projects, and the key institutions involved in the coalition. After receiving Phase 1 concept proposals, the EDA undertook two months of review to determine which coalitions would be awarded $500,000 technical assistance grants and invited to apply for Phase 2 funding. Those resources enabled a hyper-intensive planning sprint between December 2021 and March 2022. During this period, each of the 60 Phase 2 finalist coalitions expanded their five-page concept proposal into an overview narrative and project proposals that outlined their approach, key assets and institutions, the portfolio of projects and their expected outcomes, and matching resources to complement the EDA grant.

Ultimately, the 60 coalitions submitted funding requests well beyond the BBBRC’s $1 billion allocation. The average Phase 2 funding request submitted to EDA was approximately $75 million, while the average award amount available in the competition budget was approximately $50 million. Given this gap, in May 2022 all 60 applicants were offered the opportunity to prioritize funding through a budget request reduction process after applications were received. Then, an Investment Review Committee (IRC) assessed all completed applications and made recommendations. In some cases, the EDA ultimately selected a subset of component projects for funding or funded component projects at a reduced level, requiring applicants to modify projects during the award process. In September 2022, the EDA selected 21 of the 60 coalitions for implementation awards, ranging in size from $25 million to $65 million, to be spent over a five-year period.

Background

Wichita, Kansas’ identity as the “Air Capital of the World” was solidified during World War II, when the U.S. government selected the city to manufacture B-29 “Superfortress” bombers to fight the Axis powers. Of the four locations making B-29s, historian Arthur Herman wrote that “the first, and most important, was Wichita.” The region was a natural choice for aviation production; its flat land and clear conditions meant that production could continue year-round, and the presence of Boeing, Cessna, and Beechcraft meant the region had been building its capabilities in aerospace manufacturing since the 1920s. Yet the scale of the B-29 effort changed the region forever. Prior to the start of the war, approximately 1,500 people worked in Wichita’s aviation industry. By 2001, the aerospace industry employed more than 45,000 people in the region.

While that number has declined over the past two decades, over 30,000 people in the region still work in Wichita’s aerospace cluster. The region’s employment concentration in aerospace product and parts manufacturing is an astonishing 33 times higher than the U.S. overall—the highest in the nation. Spirit AeroSystems, Textron Aviation (which merged Cessna, Beechcraft, and Hawker Aircraft), and Bombardier Learjet all call the region home. In addition to its civilian applications, Wichita’s manufacturing cluster is an important supplier for the Department of Defense. While aerospace is the region’s anchor industry, South Kansas has substantial capabilities in many manufacturing industries, ranging from agricultural machinery to HVAC equipment and beyond.

With aerospace central to South Kansas’ economic fortunes, the region has made critical investments in research and talent development over the past three decades to sustain its competitiveness. One leading example is Wichita State University’s (WSU) National Institute for Aviation Research (NIAR). Established in 1985, today NIAR has six sites across the region and world-class capacity in critical areas of aerospace research, including composites and advanced aerospace materials, manufacturing processes such as automation and additive manufacturing (colloquially known as 3D printing), and others. Partly due to NIAR, WSU is ranked third nationally among all universities in aerospace research and first in industry-financed aerospace research, despite the fact that it is not a “research 1” (R1) university.

In addition to NIAR, WSU also has a unique agreement with WSU Tech, a two-year institution in the region. Founded as Wichita Area Technical College, in 2018 WSU Tech and WSU established an affiliation that has allowed these two separate, degree-granting institutions to maintain a level of partnership and integration rarely seen across higher education. Many classes WSU Tech offers are transferrable to WSU, and the schools’ “Shocker Pathway” allows students to start their associate degree at WSU Tech and finish it at WSU, providing them with a pathway to a four-year degree.

These assets come together in one physical place at the National Center for Aviation Training (NCAT), which houses both WSU Tech classrooms and select NIAR laboratories for aviation and manufacturing. NCAT, one of the premier aerospace training institutes in the world, provides WSU Tech students with skill development opportunities that meet regional industry workforce needs, such as the Get to WERX earn-and-learn program.

A recent history of regional economic planning in South Kansas

South Kansas’ BBBRC success stemmed in part from sustained regional planning efforts that crafted an economic vision for the region and developed the collaborative capacity to act on that vision. In 2008, the Department of Labor’s $5 million Workforce Innovations in Regional Economic Development (WIRED) grant helped the region determine that its true labor shed spread over a 10-county region. In 2015, WSU—alongside a broader coalition of governments, economic development organizations, and civic groups—led the creation of the Blueprint for Regional Economic Growth (BREG), an economic development plan focused on eight clusters identified as core to regional growth. BREG was followed by plans to grow exports and attract foreign direct investment, as well as an updated regional blueprint in 2018.

These efforts were foundational as the region applied to the BBBRC in 2021. At that point, South Kansas was being tested anew by three critical developments in the aerospace industry. First, as incomes continue to grow throughout the world, so does demand for air travel. To keep up with projected demand, an estimated 40,000 additional commercial aircraft will need to enter service globally in the next 20 years—almost twice the number that are in service today.

The second development that shaped South Kansas’ BBBRC strategy was the grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX from March 2019 to December 2020. Because all 737 MAX fuselages are built by Spirit AeroSystems in Wichita, the grounding caused significant disruption, with Spirit laying off around 5,000 workers during that time.

The third development was the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, which caused a decline in air travel just as the region was trying to scale up manufacturing capacity to move past the 737 MAX grounding. South Kansas leaders estimated the loss of demand for air travel during the pandemic cost the Wichita region 20,000 jobs.

These three developments yielded a critical challenge—and opportunity—for the region: How can Wichita maintain its strengths in aerospace manufacturing while also continuing to diversify into other related advanced manufacturing industries? Meeting that objective requires investment in talent and technology to ensure that the region’s workers and firms can integrate the advanced technologies at the core of modern manufacturing.

Broader labor market dynamics in Kansas bring added urgency to meeting this technological imperative. The Wichita metro area—and the state overall—has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the nation. That tight labor market has yielded wage gains for workers, but also created hiring challenges for the region’s small and midsized manufacturers. As Wichita’s workforce ages, these labor supply pressures have become even more acute, which raises the need to create training programs that are accessible to a broad and diverse swath of the region’s workforce. Additionally, new technologies can help the aerospace cluster adapt in periods of tight labor demand and remain competitive over the long term. Yet these technologies are often expensive, especially for small manufacturers, and so require intentional efforts to increase adoption.

And while South Kansas currently has strong growth and low unemployment, the potential for future shocks to the aerospace industry could affect the region’s economic trajectory. This was evident over the course of 2023 and into early 2024, most notably in the grounding of the 737 MAX 9 in early 2024. To date, these challenges haven’t affected the implementation of the region’s BBBRC strategy. Indeed, to the extent that firms in the aerospace industry must now operate at an even higher level of safety and precision, they will benefit from the increased adoption of advanced technologies that the region’s BBBRC strategy is supporting.

Coalition formation

This section explores how WSU organized a coalition of economic development, government, and labor organizations; developed a portfolio of projects to respond to Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the BBBRC; and narrowed that portfolio to a series of investments to support workforce development and technology adoption across small and midsized manufacturers. Coalition formation benefited from a history of collaboration between these actors, facilitation from WSU, and motivation to respond to clear challenges and opportunities within the aerospace cluster and advanced manufacturing more broadly. The coalition’s project portfolio will be of interest to leaders in industry and especially higher education who want to support technology adoption among manufacturing suppliers.

Aligning the coalition around a call to action

When the Notice of Funding Opportunity for the BBBRC was released in August 2021, there was widespread consensus that Wichita’s aerospace cluster should be an important focus of the strategy. Rising global demand in the aviation travel market represented a sizable new opportunity, even as the shocks to the region from the 737 MAX grounding and COVID-19 demonstrated the risks of overconcentration in just one industry and underscored the need to diversify into new ones.

The South Kansas Coalition eventually aligned around a shared called to action: to empower equitable adoption of productivity-enhancing emerging technologies for sustainable precision manufacturing competitiveness and profitability. That call to action gave rise to the coalition’s BBBRC strategy, named “Driving Adoption: Smart Manufacturing Technologies.”

How did they arrive at this call to action? Private industry was a critical stakeholder in the BBBRC coalition formation process—both original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and the small and medium-sized manufacturers (SMMs) who act as suppliers for the OEMs. While no OEMs are headquartered in Wichita, their decisions loom large on the region’s network of suppliers. This is best exemplified by the close relationship between Boeing and Wichita-based Spirit AeroSystems, but the region has over 450 general, commercial, and defense aviation suppliers in total. With the substantial anticipated growth in global demand for commercial travel, OEMs have a greater need for suppliers than ever before. And with continued ambiguity about the future of global supply chains, both companies and the U.S. government are interested in developing a robust domestic supplier market for critical industries such as aerospace. Regions that already have a substantial industrial base in the relevant industries, such as South Kansas, are essential to developing those markets.

This supply chain stretches across a vast geographic region, economically connecting urban Wichita with its outlying rural areas. Aerospace and other manufacturing firms are mostly based in the Wichita metropolitan statistical area, where they maintain both design and manufacturing presences, but have important linkages to rural areas where manufacturing also takes place. Expanding on the WIRED grant labor shed, the South Kansas Coalition serves a 27-county South Kansas labor basin.

Yet there are disconnects between OEMs and suppliers that could potentially hinder a supplier-dominated market such as Wichita. For all their reliance on supply chains, OEMs do not typically invest in assisting SMMs become part of their supply chain; it is up to the SMMs to find their own resources to meet the OEMs’ demands. Given the significant role that SMM suppliers play in Wichita’s economy (as well as their importance for developing and expanding domestic supply chains), the coalition viewed it as critical to invest in the capabilities of its supply chain.

WSU, and particularly NIAR, was instrumental in identifying the industry needs outlined above and translating those into a coherent call to action for the BBBRC strategy. In comparison to other research universities, WSU is uniquely involved in regional economic development issues. Andrew Nave, executive vice president of economic development at Greater Wichita Partnership (GWP), noted that he had “never found a [university-based] economic development group that is as closely tied in” as WSU’s economic development team is with the South Kansas region, owing to two decades of prior planning efforts. Importantly, WSU also had extensive experience in bringing federal grants and connections to the region. Over the last 10 years, WSU has acquired funding for ecosystem support from a variety of federal agencies. This put WSU in a natural position to be the lead organization for the coalition.

Project identification and selection

As the South Kansas Coalition operationalized their strategy into specific projects, they focused on foundational, capacity-building investments for the region’s base of SMMs. As Debbie Franklin, WSU’s associate vice president of strategic initiatives and the coalition’s regional economic competitiveness officer (RECO), said, “We can’t build a second floor without a sturdy foundation.”

The coalition determined this economic foundation should have twin pillars: 1) an educated workforce for the future; and 2) technological capability among SMMs. Within those pillars, Franklin noted that project selection focused heavily on “turbo-charging” market-ready technologies and their adoption in the region. Andrew Nave at GWP agreed, simply asking, “Where can we do the most good?” To determine this, the coalition worked closely with equipment manufacturers, technology experts, and organizations using that equipment to determine which products and technologies were ready for the market, such as cutting-edge metallic additive manufacturing and hybrid robotic manufacturing.

The value of these technologies to SMMs specifically was an additional determinant of project identification and selection. South Kansas’ 450 supplier machine shops vary in size, with a wide range of capabilities and technological adoption strategies. However, evidence has long shown that small manufacturers have more barriers to adopting cutting-edge technologies than larger manufacturers. Given these barriers, the coalition aimed to build out projects that could help make SMMs in the region more efficient. In some cases, that would mean promoting technological adoption, such as by helping manufacturers that are still bending steel or stamping parts transition into new materials such as composites and metal alloys, which constitute the future of the industry. In other cases, it could involve connecting suppliers to other firms in the region to support deeper supply chain development and expand their customer bases. Across all these cases, SMMs’ ability to make these transitions will depend on the technical capabilities of their workers, which is why investing in the talent base is also crucial.

Building the project portfolio coincided with a coalition-building effort that brought together labor, economic development agencies, and business organizations in the region. Business and economic development organizations such as GWP and the Wichita Regional Chamber of Commerce are supporting broader regional planning in partnership with the coalition, such as through executing the region’s talent roadmap; leading diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives for the coalition; and helping with metrics development. The BBBRC coalition also included labor organizations, such as its work with the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Manufacturers, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace, which supported the talent roadmap and the coalition’s technical report on smart-manufacturing technologies.

Through this planning process, the focus of the BBBRC strategy became clear: to put regional SMMs on a healthy long-term financial footing to ensure the future sustainability of the region’s manufacturing clusters in an increasingly competitive national and global market. On its Phase 2 application, the coalition proposed six interconnected projects to do this:

- Additive Manufacturing. This project would focus on equipping small and medium-sized businesses in the region with the tools and training needed to incorporate additive manufacturing techniques into their operations and supply chains.

- Semiconductor Testing and Evaluation Laboratory. This project would create a teaching laboratory to improve microchip quality and performance, with a specialization in measuring the gases sealed in microchip packages.

- Smart Manufacturing. This project would create a scaled laboratory and training curriculum to support the adoption of smart-manufacturing technologies among SMMs in the region.

- Smart Manufacturing Network and Talent Convening. This project would convene a network of actors from across the region to share smart-manufacturing best practices and expand access for individuals from underrepresented groups into smart-manufacturing careers.

- Construction of Smart Manufacturing and Applied Research Training Facility. This project would build a new facility to consolidate training of WSU and WSU Tech students as well as industry workers in the skills needed to access regional aerospace and other smart-manufacturing careers.

- Governance, Management, and Evaluation. This project would establish a Technical Advisory Panel (TAP)—an interorganizational network of leaders to provide high-level vision, strategy-setting, and governance for the coalition, as well as to support regional DEI efforts.

Since Phase 2 funding requests exceeded the BBBRC’s available resources, the EDA gave all Phase 2 finalists, including South Kansas, the opportunity to reduce their budgets. In deciding what to cut, the coalition again leaned on its philosophy of choosing projects that were closest to market-ready, and scaled back on those that were longer-term goals. There were several foundational elements that the coalition consciously avoided cutting. One was the budget for equipment purchases, which are central to developing the region’s cutting-edge technical capabilities. Another was funding for training, which is essential for developing the region’s human capital. The group submitted a revised proposal for four of the six projects, which were ultimately selected for implementation awards by the Investment Review Committee:

- Enhancing Adoption of Additive Manufacturing in Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturers (Additive Manufacturing)

- Encouraging Application of Smart Manufacturing Technologies (Smart Manufacturing)

- Creating a Hub for Advanced Manufacturing and Research (HAMR)

- Managing Coalition-Wide Governance and Evaluation

For each project, the implementing organizations are either based at WSU or work closely with WSU—reflecting the tight integration and strong coordinating role that the university played in this process. The coalition was ultimately awarded $51 million in federal funding. WSU itself provided most of the coalition’s $13 million in matching funds, paired with $485,000 in matching funds from WSU Tech for the Smart Manufacturing project, and $250,000 in matching funds from the state of Kansas for the governance and evaluation project.

Embedding equity in the strategy

Finally, through the strategy development process, the coalition aimed to be responsive to the EDA’s goals around equity. In particular, the coalition and others in the region are aware of the misperception of Kansas as lacking diversity, and are aiming to change that assumption. As mentioned above, the Chamber and GWP have spearheaded many of the coalition’s DEI efforts. For example, the Chamber is leading a DEI Advisory Committee researching initiatives to bolster inclusion across different industries in the region (discussed further below), while GWP, which operates as a business membership organization, is also supporting this effort by working with its member companies on issues related to DEI. The coalition also emphasized the business importance of diversity to its constituents. In a region where the manufacturing workforce in particular skews older—and out-migration is happening among younger workers as well as women and workers of color—having a workforce that represents a broad range of ages, races, ethnicities, and abilities can be a business and talent attraction asset for companies.

WSU has defined “historically excluded communities” across several dimensions. Inequality by race, ethnicity, and gender are all important dimensions, particularly because Latino or Hispanic residents are the fastest-growing population in the state. However, the coalition is also interested in measuring outcomes across language lines, given the region’s significant Latino or Hispanic and Vietnamese communities. Finally, WSU expressed an interest in measuring outcomes for other communities such as LGBTQ+ residents; however, they noted those communities may be more difficult to measure because of their smaller population size and relative oversight in federal data. Coalition RECO Debbie Franklin noted they were grappling with the question: “How do we build diversity metrics in a way that we aren’t just working backward from federal data?”

As with other areas of the coalition, trust and long-term collaboration also play a significant role in equity efforts. The South Kansas Coalition covers a broad, 27-county region that includes the city of Wichita (with a population of nearly 400,000) as well as rural counties with fewer than 10,000 residents in total. The region contains an array of views on how critical DEI efforts are for their firms and communities. One of the most important factors in successfully navigating these dynamics has been having credible organizations such as WSU and the Chamber championing the importance of DEI. Because of the deep working and interpersonal relationships that coalition members such as WSU and the Chamber maintain with companies in the region, some companies that otherwise may not be interested in DEI efforts are willing to engage on the topic.

One coalition member emphasized the potential value of DEI training for firms in the region. Stakeholders noted the value of certifications by organizations such as the Society for Human Resource Management, which helps companies and employees improve their DEI policies and processes. Stakeholders felt that these training courses could significantly aid in educating business leaders and others in the regions on proactive DEI efforts and programs. A coalition member noted this type of training can also be helpful in letting firms know what DEI looks like beyond the South Kansas region.

Moving forward, coalition members mentioned the importance of leveraging procurement to support equity in the region. The Chamber has taken steps on this front, such as partnering with the city of Wichita in 2020 to form an Equity Partnership focused on supplier diversity. Coalition members discussed additional ways that the region can align its DEI efforts, such as by developing training for purchasing managers at companies to allow them to structure their bid processes in ways that are more inclusively competitive. One barrier to doing more on this front is the state policy context in which the region’s municipalities and higher education institutions are operating. One coalition member noted that the procurement process for public entities is set by the state of Kansas, and any procurement policy modifications must be coordinated at the state level.

Implementing the strategy

Since receiving its BBBRC award in fall 2022, the coalition has made implementation progress across each of its four projects. This section explores the early successes and challenges of implementation, which have implications for other regions. The coalition’s work will be useful to other regions where universities want to play a more significant role in supporting technology adoption and talent development in an advanced manufacturing industry. It offers lessons in how other regions can not only design and execute investments in buildings and equipment to support innovation at small and midsized companies, but also the types of outreach and supportive programming that managers and production workers at those firms need to successfully utilize that innovation infrastructure. Knowing what is happening in South Kansas is critical to understanding the on-the-ground steps needed to secure the country’s advantage in global supply chains, revitalize domestic manufacturing, and bolster long-term national competitiveness.

Enhancing Adoption of Additive Manufacturing in Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturers

Led by WSU, this investment—which received $17 million in EDA and local matched funding—equips SMMs in the region with the tools and training needed to incorporate additive manufacturing techniques into their operations and supply chains. Additive manufacturing is the process of using computer-aided design (CAD) and other computer technologies to deposit materials layer-by-layer into precise shapes. It contrasts with traditional “subtractive manufacturing,” which shapes objects by removing pieces of a larger raw material. Additive manufacturing matters because it can be cheaper and—importantly for the aerospace industry—more precise than traditional manufacturing. However, the equipment and knowledge to begin leveraging additive manufacturing can be cost-prohibitive for SMMs.

This project has four key sub-components: 1) creating a set of regulatory and guidance documents for industry; 2) conducting qualified factory development audits; 3) establishing a materials standards and material property database; and 4) creating a set of hybrid technical trainings, each of which contributes to firms’ successful adoption of these technologies.

Information is an initial barrier for SMMs to adopt additive manufacturing techniques—specifically, the lack of clear guidance on the qualifications required to be an additive part supplier for a major OEM or government agency. So an initial step in implementing this project was to create an industry-reviewed white paper to guide SMMs in becoming additive part suppliers for the aerospace industry. To conduct this work, NIAR convened a working group with representatives from government and military agencies alongside aerospace OEMs such as Boeing and General Electric to discuss a common approach to additive manufacturing qualification for critical applications. The white paper will guide manufacturers to achieve qualification to sell manufactured parts to OEMs and government agencies. NIAR published the white paper in early 2024.

However, information alone will not yield adoption. Therefore, in addition to developing standards that companies in the region can work toward to become qualified factories, NIAR is developing a process to conduct qualified factory audits for manufacturers in the region. NIAR will work with SMMs and leading standards organizations to audit their factory processes and bring them in line with the standards and processes laid out in the white paper. This audit process will be tied to existing industry guidance to ensure rapid adoption and acceptance within the industry.

Third, SMMs need access to the material inputs for additive manufacturing. Thus, NIAR is creating a material standards and material property database to allow potential manufacturers to explore the properties of various materials that can be used in additive manufacturing. This matters because additive manufacturing encompasses a wide variety of printing materials, methods, and equipment—all with varying specifications and material properties that make them suited for vastly different use cases. These materials are categorized into two broad categories: metals (which are conductive) and polymers (which are non-conductive). Given this variability in materials and production, manufacturers interested in adopting additive manufacturing techniques need to understand the properties of the different materials and printers that are available to them. Cost is also a prohibitive barrier for SMMs. The material standards and material property database that NIAR is creating with funding from its BBBRC work will help manufacturers in the region overcome some of these barriers. Once it’s completed, companies will be able to use the data to test their manufacturing processes and create prototypes. Both the metal and polymer databases are anticipated to be online by the end of 2024.

The final element needed for adoption is a skill development pathway to prepare workers to successfully use additive manufacturing technologies. This element was enacted in the fourth sub-component, which is creating a set of hybrid technical classes for additive manufacturing. These trainings require developing proficiency on physical equipment, which meant that early implementation involved procuring new equipment. In the months immediately following the award, the global supply chain challenges that emerged in the wake of the COVID-19 recession delayed several deliveries of new equipment to the coalition. The coalition responded to these supply chain challenges by first focusing on training for prerequisite skills that could be taught before the equipment was delivered. This included developing trainings on how additives work as well as on foundational skills such as understanding additive manufacturing’s industrial impact and workflow, basic CAD training, and standards overviews.

A key lesson for leaders in other regions pursuing similar approaches is that additive manufacturing adoption—as with other advanced manufacturing technologies—requires new skills training for both company decisionmakers (who must feel comfortable enough with additive manufacturing techniques to adopt them) as well as workers themselves (who will be using the new technologies on a day-to-day basis). To support the first group, the coalition launched an Additive Manufacturing for Policy Makers, Decision Makers, and Executives workshop, which it held in person in May 2023 and online in August 2023. For workers, the coalition has developed and tested introductory, intermediate, and expert-level additive manufacturing training for design and production personnel. To promote broad applicability across different firms, the coalition decided to modularize some trainings to allow for better customization to individual company needs.

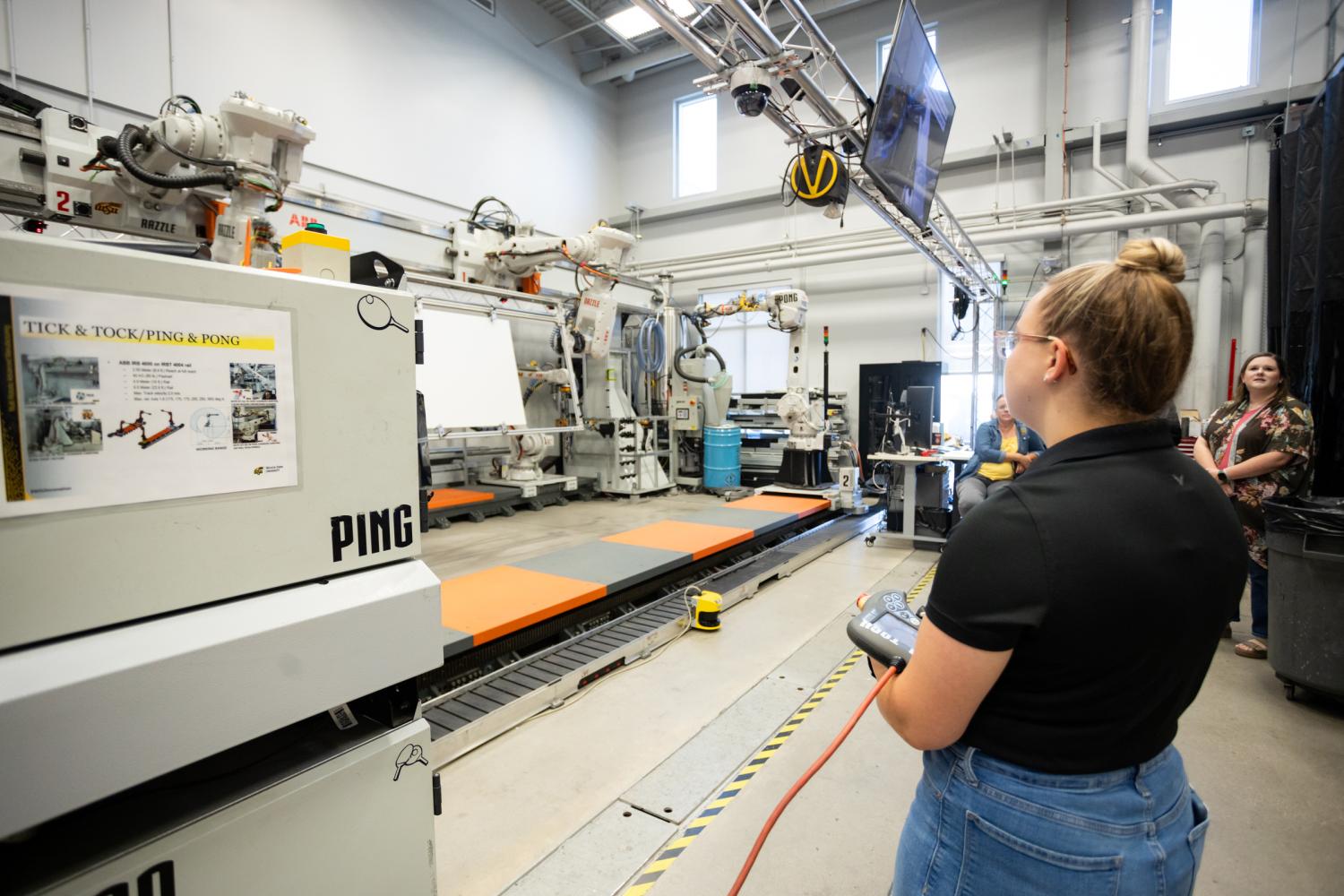

Encouraging Application of Smart Manufacturing Technologies

The smart-manufacturing project’s goal is to encourage greater application of emerging technologies among South Kansas manufacturing firms, such as additive manufacturing, artificial intelligence, and digital systems. Smart-manufacturing techniques allow for product and process improvements that help U.S. manufacturers stay globally competitive, and so there is a both a regional and national imperative to disseminate their use.

However, manufacturing companies may not always know how to incorporate such technologies into their production processes. And it can be cost-prohibitive for manufacturers, particularly SMMs, to build a full lab to test out these new technologies and techniques. To fill this gap, regional actors can build an “industrial commons,” which allow companies to test emerging technologies in a representative environment without needing to commit to fully building out a lab themselves. Such industrial commons are also useful for training students and workers on emerging manufacturing technologies, and so universities can be natural homes for them. Debbie Franklin, the coalition’s RECO, explained that this project will have three primary goals: supporting workforce development, supporting industry product development needs, and conducting research.

Through this project—which received nearly $11 million in EDA and match funding—WSU Tech is setting up a scaled lab, or a “representative laboratory,” for a smart system. These types of labs, also known as “learning factories,” straddle the line between full physical shop floors and fully digital models. They consist of a small-scale physical shop floor, which creates a realistic platform for conducting smart-manufacturing research and training without building a full, real-world production line (which is prohibitively expensive) or relying entirely on simulations (which don’t always perfectly emulate real-world conditions). Within this project, WSU Tech is both acquiring the equipment needed for such a factory as well as developing curricula on smart-system management for various stakeholders in the region’s manufacturing ecosystem, all in conjunction with industry partners.

To implement this project, the coalition first needed to increase its staff capacity. In 2023, WSU Tech hired new staff to fill BBBRC-funded positions, including a project manager, smart-factory faculty member, and lab assistant. WSU Tech initially had challenges with securing qualified applicants for their project manager and lab assistant positions, largely because the salary that they could offer as a two-year public institution was not competitive with the private sector. After reevaluating the positions’ pay structures, they were able to make the hires. However, in late 2023, the project manager left for a new opportunity, meaning the position was again vacant. Utilizing lessons learned via the smart-factory environment planning stage, WSU Tech quickly pivoted to focus on part-time specialists, and they were fully staffed by the end of January 2024.

A key point that coalition members emphasized in interviews was that most of the curricula design cannot happen until the factory is set up and the equipment is delivered. As Scott Lucas, vice president of aviation, manufacturing, and institutional effectiveness at WSU Tech, said, “You can’t really design a curriculum without knowing what the lab will look like.” As with the additive manufacturing project, ordering equipment has been a substantial component of this work. Similar to the additive equipment and database being ordered through the additive manufacturing project, manufacturers in the region will have access to the smart-manufacturing equipment that WSU Tech is procuring. The pace of this project has been affected by the global supply chain crises of 2022 and 2023. Initially, the procurement process was delayed due to procedural requirements outlined under federal, state, and university policy. Once awarded, lead times were still unexpectedly long, primarily because the systems are custom built for the region’s specific use case scenarios.

To support the scaled lab, WSU Tech is creating an Industrial Internet of Things (IIOT) network and infrastructure to connect existing manufacturing laboratories and equipment to recreate a smart-factory production environment. An IIOT uses internet-connected smart sensors to connect existing “dumb” manufacturing machines to the internet. Doing so allows an organization to create a network linking the different machines in a factory or laboratory together—enabling users to capture and analyze new data that can greatly improve production processes.

To take full advantage of these technologies, WSU Tech is developing a curriculum to train workers in the region. To develop the training, the project team at WSU Tech assembled a Business and Industry Leadership Team composed of national partners, local and regional manufacturing partners, and integration and support partners, and engaged with over 50 industry, vendor, and state accreditation entities to ensure the training being developed meets the regional skill needs of industry partners.

One of the most significant partnerships that WSU Tech developed during early implementation was a partnership with Cisco Systems for consultation, support, and equipment to set up the connected smart-manufacturing labs and classrooms. The coalition is looking to build an industry-agnostic Smart Factory designed to be a platform for adopting smart-manufacturing techniques across manufacturing companies of all types and sizes. As a result, the equipment selected for the factory must have sufficient use cases to prove it can be used across multiple industries, ranging from medical devices to HVAC manufacturing. In support of this goal, Cisco provided many of the supplies for the Smart Factory setup at reduced or no cost.

Historically, different industries have used highly customized technology tailored to specific company needs. However, Cisco is aiming to transform smart-manufacturing technologies from that of specific, company-level customization to one of “mass customization,” where there are a few baseline technologies that can be tailored to specific industry or company needs. Given the shared interest in broad industry adoption of smart-manufacturing technologies between both Cisco and the coalition, this partnership dovetailed with both organizations’ goals.

In addition to Cisco’s support for the Smart Factory equipment, WSU and WSU Tech are closely collaborating with the company on the development of a curriculum focused on IIOT. The WSU-WSU Tech partnership is one of only two institutions globally that will pilot this new curriculum and the only one focused on manufacturing.

Despite the barriers the coalition faced, it has been able to take a variety of steps to develop the worker training that is core to this project. The coalition reported that it offered two classes in its first year: a 2023 summer camp class on Virtual Robotics and Potential Platforms, and a December 2023 introductory course on Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing, which assists manufacturers in controlling for slight differences in the dimensions of manufactured items between when they are designed on a computer and manufactured in real life.

Creating a Hub for Advanced Manufacturing and Research

This goal of this project—which initially received $35 million in EDA and match funding and subsequently received another $16 million in state funding—is to co-locate many of the coalition’s additive manufacturing and smart-manufacturing assets in a single hub, with the aim of growing the region’s training capacity and enhancing access and efficiencies for researchers and companies. To do so, the coalition is constructing the Hub for Advanced Manufacturing and Research (HAMR) on the WSU campus, which will host a significant portion of the coalition’s BBBRC equipment and training facilities. The South Kansas Coalition’s experience standing up the HAMR has important takeaways for other regions exploring how to effectively create industrial commons.

A key consideration for regions taking on similar work is requirements around real estate. In its original application, the coalition planned for the HAMR to be located on the WSU Tech campus. However, because Kansas state law requires that any state-funded projects be built on state-owned land, construction needed to be moved to the WSU campus. After the building site was moved, in 2023 the state of Kansas invested an additional $16 million into the project to add a second floor and further enhance the co-location benefits of the building. This change delayed the start of construction by an estimated two months. Construction began in spring 2024 and is expected to be completed by fall 2025.

Another consideration for regional leaders is the need to continually communicate with stakeholders during a prolonged, multi-phase construction process. Currently, BBBRC activities are distributed across various temporary locations across Wichita, which has caused some confusion among stakeholders about where and how the BBBRC activities will occur. While construction continues, WSU has been conducting proactive outreach to guide the community about the future state of the BBBRC effort for the university and region.

Consolidating much of the BBBRC’s strategic work into one physical location will ease this confusion. When completed, most of the additive manufacturing project’s equipment will be moved to the HAMR building, as well as some of the smart-manufacturing project’s equipment (some smart-manufacturing equipment can’t be physically moved and so will remain at NIAR’s newly established Advanced Manufacturing and Prototyping facility north of Wichita). Likewise, the classroom work for the additive and smart-manufacturing projects will take place in the HAMR building.

Managing Coalition-Wide Governance and Evaluation

Through this project, the coalition has assembled a Technical Advisory Panel (TAP) to lead its governance and evaluation work, utilizing a little over $2 million in EDA and match funding. The TAP is an intergovernmental network consisting of leaders from regional organizations, including the Kansas Aviation Research and Technology Growth Initiative (an industry-led growth effort established in 2003); GWP and the Regional Economic Area Partnership (economic development organizations); the Chamber, the Wichita Manufacturers Association, and the Wichita Independent Business Association (associations with regional leadership and momentum in the implementation of DEI priorities); and labor representatives.

In terms of overall governance, the South Kansas Coalition describes itself in its application documents as “convened by WSU” with “vision and component projects governed through the TAP.” Through biannual meetings, the TAP will review and course-correct project work plans, as well as provide high-level strategy input from the perspective of regional well-being. The TAP also plans to convene task forces and roundtables on topics of interest, such as exploring firm retention and expansion; enhancing the community as a place to live, work, and develop a business; and economically empowering regional residents.

Day-to-day implementation of the strategy is led by WSU and organizations affiliated with it. Coalition activities are managed by WSU’s Office of Strategic Initiatives, which is overseen by Debbie Franklin, WSU’s associate vice president of strategic initiatives and the coalition’s RECO. Franklin works with the Strategic Initiatives project management team to coordinate the coalition’s work. The project management team meets regularly with operational units within the coalition that are overseeing its work. Each project has a different cadence and meeting style with the Strategic Initiatives project management team. Some projects maintain standing weekly meetings, while others have regular site visits. All the component projects have regularly scheduled management meetings at least once a month with the Strategic Initiatives project management team. In addition to its bi-annual leadership meeting with the TAP, the WSU Strategic Initiatives project management team also maintains standing individual meetings with specific TAP members.

This project also supports evaluation and metrics reporting, discussed in more detail below.

South Kansas stakeholders emphasized two key themes around early implementation outputs. First, trust was necessary to have early implementation successes. Second, the organizations in the coalition had developed trust by working together for years before the BBBRC grant. As Ricki Ellison, director of talent, workforce development, and community engagement at GWP, told Brookings, the level of trust that different actors in the coalition have with one another makes it more efficient and effective at implementing its strategy:

The key here is trust. Early on, we engaged in discussions about our strategies. We trust that stakeholders are executing their responsibilities based on their expertise. Each of us has specific tasks and [key performance indicators] that are gaining importance. Instead of a centralized system where we constantly seek guidance from WSU, we operate with trust and autonomy. We confidently assign responsibilities, saying, ‘I believe you've got this. Provide an update at our next monthly meeting.’

Ricki Ellison, director of talent, workforce development, and community engagement at GWP

Focus on equity in implementation

The coalition has made DEI a core part of the strategy, but faced two headwinds that have shaped its strategy around it. The first, as previously mentioned, is that the region is—incorrectly—perceived as having little diversity, which can hinder firm and talent attraction and economic development efforts. The second is that most of the coalition’s projects have a highly technical focus, centered on firms’ technology acquisition and adoption. As a result, the coalition must address the long-standing inequality and exclusion that have occurred in highly technical work.

The coalition actively supports DEI efforts through several vehicles in implementation. The first involves the students WSU and WSU Tech choose to enroll. WSU has experienced growing enrollment numbers and an increasingly diverse student body. This includes the university’s recent designation as an Emerging Hispanic Serving Institution. Meanwhile, WSU Tech, as an open-access institution, serves students from an array of racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. Their inclusion in the coalition’s work is essential to the region’s DEI efforts.

Business development organizations that are members or partners of the coalition—such as GWP and the Chamber—are also running dedicated efforts to support DEI at businesses and industries in the region. Since 2020, the Chamber has hosted a DEI Advisory Committee comprised of leadership from major firms in the region, which has now become a key component of the BBBRC effort. The committee focuses primarily on how DEI affects the business community, with the goal of ensuring it has a positive impact on business through benefits such as increased revenue and talent retention. Committee meetings are a venue for members to share their respective DEI efforts and discuss goals that members would like to see accomplished during the next strategic planning effort from 2024 to 2027. During this period, the Chamber launched its new DEI website to increase awareness and knowledge among local businesses in support of their DEI efforts, followed by a three-part DEI Development Series held throughout 2023, which it plans to continue in 2024.

Working alongside the Chamber to support DEI efforts is GWP, an economic development organization that supports regionwide growth and downtown redevelopment and placemaking. GWP’s DEI focus complements the Chamber’s work by supporting talent pipeline development, career access, and other elements of workforce equity, such as access to child care, transit, and affordable housing. In line with the region’s BBBRC effort, GWP has launched a new skills navigator platform to connect workers to good-paying jobs. GWP’s launch of the platform aligns with the launch of the FutureReady Centers, a collaboration between WSU Tech and Wichita Public Schools that has connected over 150 students from high schools with the highest ratios of underrepresented students to manufacturing and health careers.

Tracking implementation and outcomes through metrics

Tracking outcomes for a comprehensive regional strategy involves metrics at multiple levels. The South Kansas Coalition is tracking two types of metrics: programmatic metrics and ecosystem metrics. Programmatic metrics measure progress across the coalition’s five funded projects, while ecosystem metrics will measure a set of regional economic indicators to help track the BBBRC’s influence across the region’s economy more broadly (for example, the coalition created an Economic Distress Index to measure overall economic prosperity in the state and region). The coalition is creating a public-facing site for tracking all metrics, both programmatic and ecosystem. As it constructs this tool, several questions emerge, with relevance for other coalitions considering this type of regional transformation:

- Over what time horizon should we measure progress and from what baseline?

- How can diversity, equity, and inclusion be embedded in the tool, including broader social metrics?

- How can surveys, such as one assessing industry sentiment on DEI, complement government-provided economic data?

Coalition members emphasized that while metrics and key performance indicators are important, their goal is ultimately to be transformational. As coalition RECO Debbie Franklin put it, “We’re trying to change the way America competes.” Along those lines, coalition members surfaced a series of broader structural questions that the coalition is also asking, which likely can’t be tracked in short-term metrics but will ultimately determine the success of the coalition’s—and the BBBRC’s—efforts in the region. These wider questions included: “Is aviation coming back and is it growing?” and “Are we adding other manufacturing companies that are adjacent but not quite in this space?” Coalition members also raised the topic of technological adoption as an important dimension to consider, noting that technological adoption was a core part of the coalition’s work—its strategy is even named “Driving Adoption.” However, as John Tomblin, senior vice president for industry and defense programs at WSU and executive director of NIAR, pointed out in an interview, “If a company adopts technology, it may see an employment decline. But if it doesn’t, they may go out of business entirely. So how do you measure that?”

These questions get at the complexity of measuring economic change, but one thing is clear: South Kansas coalition members emphasized that the success of the coalition, and of the BBBRC, will ultimately have to be measured across decades and will consist of much more than simply job creation numbers and key performance indicators.

Implications

The South Kansas Coalition’s experience in the Build Back Better Regional Challenge provides several important takeaways for policymakers, federal agency officials, regional economic development officials, and higher education institutions.

First, universities and university-led coalitions should build off established clusters of strength

There is substantial evidence that universities, and particularly public universities, have a variety of important economic benefits, ranging from research spillovers to improving resilience during economic shocks and improving upward mobility. However, universities have varied results when it comes to engaging with industry and economic development efforts. To the extent that universities want to play a central role in developing their regions’ economies, one lesson from WSU’s experience is to start by building off clusters that the university’s region has a deep well of expertise in—particularly clusters in tradeable industries.

For South Kansas, that industry is aerospace, and WSU has been able to develop substantial industry partnerships by proactively working with the region’s significant aerospace employers to determine their occupational needs and shape curricula to fill them. Similarly, WSU’s growing presence in research is strongly linked to their aerospace-industry-funded research, which drove the expansion of NIAR. As the industry has experienced shocks, WSU has been a vital ingredient in supporting diversification and resilience. Through the BBBRC, South Kansas is enhancing regional expertise in technologies such as additive and smart manufacturing, which are applicable across an array of industries. It is also supporting regional efforts to grow industries such as medical device manufacturing, which rely on high-precision manufacturing processes, and so share many common traits with aerospace. Universities in regions with declining industrial bases can consider taking a similar approach.

Second, public universities—particularly regional public universities—can provide a unique balance of research, cluster development, and talent development if they are given the resources to do so

Universities can be a source of up-front capital to help regions implement federal grants such as the BBBRC. WSU and its affiliates had the resources to: 1) afford out-of-pocket expenses that the EDA could later reimburse; and 2) cover the matching funds the grant requires. But beyond that, WSU plays a variety of additional roles in the Wichita region. It is a driver of economic activity and a center for world-class aerospace and other research. However, it also retains its mission as an affordable, accessible institution serving students from backgrounds that remain underrepresented in higher education. WSU can take on these different regional roles because of a long-running investment in its capacity, including support from the EDA and federal research agencies, state funding from Kansas, and research funding from the private sector. Unfortunately, not all universities are afforded the same broad support from stakeholders.

WSU refers to itself as an “urban research university.” It has also been classified by Brookings and others as a “regional public university,” which are non-flagship, four-year public institutions that maintain broad access missions and close connections to the regions they serve. Unfortunately, many regional public universities across the nation have been underinvested in for over a decade, hindering their ability to maximize their community and economic development missions. The experience of WSU and the South Kansas Coalition should emphasize to policymakers the importance of fully investing in public higher education, and in regional public universities in particular.

Third, the affiliation between WSU and WSU Tech is a unique model worth exploring in other regions

Part of the reason WSU was so well positioned to serve as the lead organization on a winning BBBRC coalition is because of the wide variety of roles that it plays in the region. It not only supports research, commercialization, firm attraction, and degree production, but it’s also closely embedded in the region’s workforce development system. The reason it can play such a substantial role in workforce development is because of its affiliation with WSU Tech and the Shocker Pathway. This affiliation between two separate, degree-granting universities allows students to receive up to 45 general education credits at WSU Tech that transfer to WSU. Students can then complete their last 15 credits at WSU to earn an associate degree and continue at WSU for a bachelor’s degree.

The Shocker Pathway further enhances the research and talent development combination for the region. Because WSU Tech is an open-access institution, it is well positioned to support workforce development activities of all types. However, many states and regions struggle to create pathways from two-year community colleges to four-year colleges and universities, which keeps their two-year and four-year institutions on largely separate tracks. It also prevents states and regions from successfully linking their workforce development and higher education systems. Affiliations such as the Shocker Pathway strengthen WSU’s role in workforce development by allowing it to consistently enroll WSU Tech students, and strengthen WSU Tech’s role in higher education by giving students of all backgrounds a straightforward way to pursue a two- or four-year degree. The research and talent development combination is further enhanced by the many shared resources across the two institutions, including the presence of several NIAR labs on the WSU Tech campus that are open to degree and non-degree students. As a result of these multiple areas of overlap, the region truly has a web of entry points for workforce development, higher education, and research—allowing it to support skill development of many distinct types.

Federal and state policymakers should explore ways to support these kinds of partnerships, including by enacting new funding streams to facilitate them in more places.

Fourth, trusted intermediaries play an important role in getting industry buy-in for inclusion efforts

In South Kansas, the business community is playing a proactive role in supporting DEI goals. This is due not only to the strong relationship that WSU is able to maintain with business community leaders, but also due to the hard work of trusted regional business intermediaries such as GWP and the Chamber.

The South Kansas Coalition is extensive, covering not just Wichita and Sedgwick County, but also a broader 27-county region. The region covers communities of various sizes and with substantially different demographics. As a result, businesses across the region place different priorities on DEI. While many firms in Wichita may see DEI as a critical imperative to remaining competitive, companies in smaller or more rural communities throughout the region may not feel that DEI efforts are as relevant.

In other cases, misperceptions of the region as having little diversity or a place that is hostile to diversity can hinder talent attraction efforts. It’s difficult to convince diverse talent to move to a region if that region isn’t perceived as being welcoming to an individual.

Organizations such as GWP and the Chamber—which have long-standing relationships with businesses in communities of all sizes across the region, and so have deep wells of trust with them—are uniquely positioned to help companies that may not see DEI as a business imperative realize why it matters for their firm and workforce. These institutions are also critical to helping the region tell its DEI story to those outside the region to support firm and talent attraction.

In short, these types of concerted efforts by trusted business intermediaries are critical to helping the region achieve its DEI goals and, more importantly, to ensuring that Kansans of all backgrounds have access to meaningful careers that provide them a quality standard of living and allow them to contribute to the region’s shared prosperity.

Conclusion

Wichita’s reputation as the Air Capital of the World started through unprecedented cooperation between the federal government and private industry. In the following decades, the South Kansas region has refined and built upon that identity, becoming a global hub of advanced manufacturing. Today South Kansas—and the world—faces a new set of challenges. An unprecedented aircraft grounding, a global pandemic, and international supply chain shocks have roiled the region, even as demand for air travel continues to climb. But as it did in the 1940s, the region has responded by leveraging cooperative investment from government and the private sector—as well as higher education—to deepen its expertise and expand its regional industrial base. Moving forward, South Kansas has the opportunity to not only emerge as an international leader in additive and smart manufacturing, but also to serve as a model for other regions on how to enable successful, regionwide partnerships between the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

EDA case study series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publications are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or other scholars.

Brookings recognizes the value it provides in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its funders reflect this commitment.

The authors thank Alex Jones, Bernadette Grafton, Ilana Valinsky, Ryan Zamarripa, Suyog Padgaonkar, Scott Andes, and Justin Tooley from the Economic Development Administration for their insights into the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and for their guidance throughout the development of this case study. For their comments and advice on drafts of this paper, the authors also thank our colleagues Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, and Mayu Takeuchi, as well as Debra Franklin, Richard Muma, John Tomblin, and Rachael Andrulonis (Wichita State University), Sheree Utash, Scott Lucas (WSU Tech), Andrew Nave, Ricki Ellison (Greater Wichita Partnership), John Rolfe (Wichita Regional Chamber of Commerce), Brett Robinson (Integra), and Cindy Hoover (Cindy Hoover Consulting, LLC). The authors also thank all local leaders, community-based organizations, economic development practitioners, regional intermediaries, higher education institutions, industry representatives, and other coalition members who participated in informational interviews and site visits throughout this project, and who provided feedback on the research insights and policy recommendations detailed in this report.

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

About Brookings Metro

Brookings Metro collaborates with local leaders to transform original research insights into policy and practical solutions that scale nationally, serving more communities. Our affirmative vision is one in which every community in our nation can be prosperous, just, and resilient, no matter its starting point. To learn more, visit www.brookings.edu/metro.

-

Footnotes

- Economic Development Administration. “FY 2021 American Rescue Plan Act Build Back Better Regional Challenge Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (ARPA BBBRC NOFO).” U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better

- Ibid.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).