A more transactional U.S. policy towards Pakistan has brought advantages, but will have limits in the longer term, writes Madiha Afzal. This piece first appeared as part of Lawfare’s Foreign Policy Essay series.

Looking back over the past four years, the Trump administration’s Pakistan policy can be divided into two phases: bilateral relations that were decidedly strained for the first two years of the administration and, since 2019, a far more positive relationship marked by cooperation on the Afghan peace process and attempts, with limited success, to boost the relationship on other fronts. The reset that occurred in 2019 was due not to Trump’s impulsiveness, but to a transactional approach driven by Pakistan’s usefulness in the Afghan peace process. It is an approach that has had its advantages, but it has run into obvious limits as well.

Seven Decades of U.S.-Pakistan Relations

Pakistan and the United States established diplomatic ties on Aug. 15, 1947, the day after Pakistan gained independence. It was a close relationship for the new country’s first few decades, especially as U.S. relations with Pakistan’s archrival, India, were relatively cold. In many ways, 1979 marked a turning point for both countries, and Afghanistan became a defining feature in their relationship over the next four decades. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan that year, Pakistan became party to the Soviet-Afghan conflict and used U.S. and Saudi money to train and arm the mujahideen. In 1989, when the Soviets exited Afghanistan, the United States left the region, fueling a visceral sense of American abandonment in Pakistan and a sense that America could not be trusted.

The U.S. relationship with India has been a second defining factor in the U.S.-Pakistan relationship. Pakistan has been sensitive about growing U.S.-India bilateral ties since the 1990s. In 1998, the Clinton administration imposed costly economic sanctions on Pakistan (to its considerable angst) for testing its nuclear weapons in response to India’s nuclear test. Concerns about U.S. preferences on the subcontinent persist. According to a 2015 Pew poll, 53 percent of Pakistani respondents said they believed U.S. policies toward India and Pakistan favored India; only 13 percent said they favored Pakistan.

After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Pakistan joined the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan. Pakistan allowed NATO access to supply routes through the country and received considerable military and security assistance in return. President George W. Bush named Pakistan a major non-NATO ally in 2004. Relations cooled during the Obama administration as concerns grew about Pakistan’s safe havens for the Taliban and the presence of al-Qaeda in the country. This history has, for many Pakistanis, fueled the belief that Republican presidents are better than Democratic presidents for the U.S.-Pakistan relationship.

A Low Point and a Reset

Enter the Trump administration and Trump’s focus on his campaign promise of getting U.S. troops out of Afghanistan. The relationship with Pakistan for the first two years of the administration was characterized by an almost-singular focus on U.S. concerns about Pakistani safe havens for the Haqqani Network. The administration said it would make economic ties contingent on Pakistan taking action against militant and terrorist groups. Things soured further in January 2018, when Trump accused Pakistan of “lies and deceit” in its relationship with America, tweeting that it took U.S. aid for nothing in return. The administration cut off $1.3 billion in U.S. security assistance following Trump’s tweet.

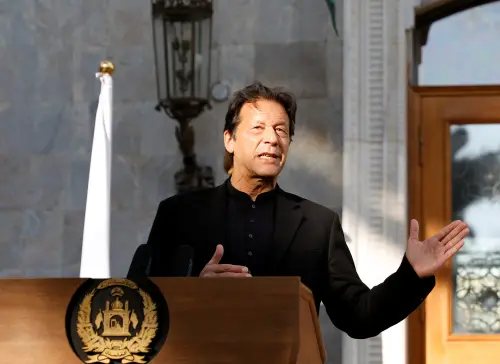

By the fall of 2018, the Trump administration seemed to have calculated that an exit out of Afghanistan would not come via a military victory. Trump appointed Zalmay Khalilzad as his special envoy to Afghanistan, and Khalilzad began the painstakingly slow work of the Afghan peace process. Though Trump had engaged in a war of words on Twitter with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan just a few weeks before, Trump wrote Khan a letter in the fall of 2018 asking for help with the Afghan peace process. Khan, who had long argued for political reconciliation in Afghanistan, was forthcoming.

The seeds for a reset had been sown. Pakistan produced Mullah Baradar, the deputy leader of the Taliban who had been in Pakistani custody. His release helped jump-start the peace process, and Baradar became the Taliban’s chief negotiator. In many ways, Pakistan was uniquely positioned to help, enjoying leverage with the Taliban and a working relationship with the United States. Khalilzad has visited Pakistan at least 15 times in the past two years. Pakistan considers the U.S.-Taliban deal signed in February a product of its help, and Khalilzad has publicly acknowledged Pakistan’s help with the process numerous times.

The hoped-for reset in the bilateral relationship was acknowledged formally during Imran Khan’s visit to Washington in July 2019, when he and Trump first met and hit it off. In a presidency where personalities have mattered a great deal, it was clear that these two celebrity-turned-populist politicians enjoyed meeting each other. They have since developed a personal connection, meeting again on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in the fall of 2019 and at the World Economic Forum in early 2020.

During the first meeting with Khan at the White House, Trump offered to mediate between India and Pakistan on Kashmir, setting off alarm bells in New Delhi—India almost immediately responded that Kashmir is a bilateral issue between India and Pakistan. Trump also called for dramatically strengthening trade ties between Pakistan and the United States. America is Pakistan’s top export destination, but these trade gains have yet to be realized.

Nevertheless, the bilateral reset has sustained. Pakistan is now helping with the intra-Afghan peace process as well, though it was not obvious that Pakistan would remain involved in this phase. Trump’s messaging on Pakistan has been scrupulously positive since the reset, something the country appreciates as it seeks to move past an image associated with terrorism. The United States has given Pakistan $8 million to help its fight against the coronavirus; Pakistan returned the favor with a goodwill gesture of personal protective equipment donations. China’s growing presence in the region, and the United States’s willingness to tolerate Beijing’s close economic and strategic ties to Pakistan, has also reassured Pakistan that major powers value its partnership.

The Advantages and Limits of a New Approach

Trump’s relatively hands-off approach to India and Pakistan has had benefits, but it has also run into limits. While Pakistan welcomed Trump’s July 2019 offer to mediate the Kashmir dispute, that pronouncement may have done more harm than good. Some Indian political analysts surmised that it might have accelerated India’s revocation of Kashmir’s autonomy, announced just a couple of weeks later, on Aug. 5. More broadly, Trump’s approach to the region has largely decoupled India and Pakistan, which has generated less concern from Pakistan about the U.S.-India relationship. India’s lack of a role in the Afghan peace process has also allayed Pakistan’s fears. Trump even mentioned his “very good relationship” with Pakistan on his visit to India—a comment that Pakistan appreciated (and that New Delhi did not like, but let go).

The Trump administration has also taken a different tack in trying to influence Pakistan. Rather than using direct assistance as a tool to drive Pakistan’s actions—which would have a limited effect given Pakistan’s economic relationship with China—the Trump administration has relied on other tools to affect Pakistan’s behavior. Most notably, the administration moved to change Pakistan’s status with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international watchdog that monitors terrorist financing, in February 2018. Pakistan was placed on the FATF increased monitoring “grey list” in June that year; the designation impedes economic investment into the country and causes it financial harm. (Pakistan had also been placed on the grey list in 2008, and from 2012 to 2015.) In its bid to avoid being blacklisted, Pakistan has since 2018 taken actions against militant groups—including placing economic sanctions on Lashkar-e-Taiba and sentencing the group’s leader, Hafiz Saeed, to 11 years in prison for terrorist financing. The Khan government has made it a key goal to come off the grey list, passing legislation to help its case. In its latest review this October, FATF announced that Pakistan has made “significant progress” and has largely addressed 21 out of 27 action items; it will remain on the grey list and has until February 2021 to address the remaining requirements. While the FATF listing is multilateral and therefore a less direct policy tool than U.S. assistance, many observers in Pakistan still perceive it as a U.S. instrument, and it is driving growing backlash in a public that perceives Pakistan’s greylisting as unfair.

Although Trump has been criticized for playing fast and loose with America’s alliances and cavorting with its foes, his Pakistan policy reveals a practical side. This more transactional approach has yielded results for the United States on the Afghan peace process and has largely been received well by Pakistan since the reset.

Yet the limits of Trump’s rhetoric and lack of homework before making pronouncements are also apparent. The trade gains Trump promised Pakistan have not materialized. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross visited Pakistan in February 2020, but the United States has had trouble investing in Pakistan due to “Pakistan’s significant business climate issues, including regulatory barriers, weak intellectual property protections, and discriminatory taxation,” according to the State Department.

With the FATF, the Trump administration has chosen an economic tool more effective than aid to encourage Pakistan to crack down on terrorist groups. So far, this approach has worked. Pakistan is eager to shed its image associated with terrorism and increasingly recognizes that global stature is driven by economic ascendance rather than strategic importance. Yet with the United States making a deal with the Taliban and giving it legitimacy, many Pakistanis have wondered why Pakistan is still maligned for its relationship with the group. The Trump administration has not offered Pakistanis the clarity they need on that front.

The Next Administration

If Joe Biden is elected president this November, he will find a different U.S. relationship with Pakistan than the one he left behind with the Obama administration four years earlier, partly because Pakistan has changed but also because of changes in the region and the Trump administration’s unique approach to the country.

The road to the U.S. reset with Pakistan in 2019 came through Afghanistan. Pakistan’s closeness with a rising China has offset some of Pakistan’s existential angst about its relationship with the United States. Trump has, against all odds, successfully balanced the U.S. relationship with Pakistan and India in a way that doesn’t worsen Pakistan’s paranoia, and the administration’s reliance on the FATF listing as a tool has also proved effective in goading Pakistan to take action against militant groups.

Yet this approach is piecemeal and opportunistic. The next administration will need to round out America’s Pakistan policy, to make it comprehensive and take a longer term view. This is especially true as the United States seeks to withdraw troops completely from Afghanistan—for the first time in more than four decades, the two countries may be looking at a bilateral relationship not driven by Afghanistan. The U.S.-Pakistan relationship, long dominated by strategic concerns, can become a productive one for both countries, if redefined carefully and with an open mind.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Evaluating the Trump administration’s Pakistan reset

October 26, 2020