In episode 3 of Quite By Accident, Steve Hess, a young staffer in Eisenhower’s administration, shares stories of feeling surprised to attend State Dinners and other formal White House functions. Host Katie Dunn Tenpas also asks Steve to reflect on Eisenhower’s leadership and the end of his administration in 1961.

- Listen to Quite By Accident on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Watch on YouTube.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

- Thanks to: Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews, senior producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video editor; Colin Cruickshank, videographer; Katie Merris, art designer; Tracy Viselli and Adelle Patten, Governance Studies communications.

Transcript

HESS: What happened, of course, was these people who were so nice to me, they gave me so much that was beyond my position above me, like inviting me to receptions, White House receptions. I mean, why was I at the reception for Khrushchev?

[music]

TENPAS: This is episode three of Quite By Accident, a podcast about Steve Hess and his life at the center of American politics. I’m Katie Dunn Tenpas, a visiting fellow and director of the Katzmann Initiative at the Brookings Institution, and a practitioner senior fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

In episode one, Steve Hess talked about how he as a young man of 25 landed a job as a speechwriter in the Eisenhower White House, and then his first impressions of working there. People were nice to him in unexpected ways, he told me, even though most of the staffers were veterans of the administration that when Steve joined was already in its seventh year.

In the previous episode, Steve talked about the job he was hired for—speechwriting—how they did it back then, and some of the speeches he worked on.

In this episode, Steve tells more stories of working in the White House in the late 1950s, some of the social functions he attended, more about the personalities he worked with, and some final thoughts on the Eisenhower administration.

[music]

Some of it sounds like a pretty good time, some of it heartbreaking.

You just heard him reflect again on his astonishment as a young man to be treated so well in the White House, and to be invited to what seemed like interesting events, like a reception for Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1959.

HESS: Why would they invite me? Well, I don’t know. They just seemed to like me. And so, I would sit there and the entertainment was Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians, and he’s playing, [dee duh duh duh duh], whatever that song is. At any rate, Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians was not what I would call a high art form. But the president in his memoirs said, I could see that Khrushchev was really enjoying this robust music. But I’m sitting right behind the Russians, and my note says they could you know, they could barely keep awake, it was so slow and … So, It was sort of funny that way.

And of course, to go to this thing, I had to get white tie and tails.

TENPAS: Wow. But you can afford it because you’re making a lot of money

HESS: Oh, I could afford it because my buddies at the White House mess tell me where to go to a place that’s going out of business where I could buy the whole thing for $37. And of course, the Russians, they’re in business suits.

TENPAS: Do you remember anything more about the Khrushchev visit? What he was like or … Did he want to meet the staff or …

HESS: Oh, heavens, no. No, no, no. We went through a receiving line for … shook our hands and so forth. We sat down, we heard dee dee doo dah music. We went home. The truth of the matter you’re home by 10:00 at night.

[music]

TENPAS: From State Dinners to riding in a helicopter, Steve had a lot of interesting experiences.

HESS4: Oh, I’d forgotten about that. The only time in my life I’ve ever ridden in a helicopter. And I’d talked to you how the helicopters land on the South Lawn, and I could see it from my window with the helicopter coming down. And Eisenhower getting off holding his fedora.

At any rate, the one trip I had was when they sent me in that helicopter out to a mountain in West Virginia. And inside that mountain is where the offices are if there were to be an invasion or something and they were moving the White House staff. And what they were doing was sending me there to see what my office would be if we had to evacuate.

TENPAS: And it was inside a mountain?

HESS: Yeah, it’s inside a mountain.

TENPAS: So, completely dark, obviously?

HESS: Well, they turned on a light when we got there. No, it was a perfectly empty office, desk chair or something.

TENPAS: Did that spook you at all?

HESS: It spooked me in a lot of ways because then I sort of think, my God, would I really leave my wife and my kids? Was I so important that I would sit in that office inside a mountain? And that’s what I thought about. That’s what I remember.

I guess when they get somebody at a certain level at the White House, that’s part of their exercise that they better show them how they will go to the Pentagon, and get the plane, and go to this mountain.

[music]

TENPAS: In episode two, Steve told me about the scarcity of women and people of color on the White House staff—in fact there were three women—all white—and one Black man during his time there. These demographic facts stood out sharply at one state dinner Steve attended in 1960.

HESS: I was invited to a state dinner. That’s very rare. A state dinner. It was there for the crown prince of Japan.

TENPAS: Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko.

HESS: And I knew why I was invited because the Crown Prince, now the emperor was 26 years old and I was 26 years old.

TENPAS: They were showcasing the youth?

HESS: They were showcasing me, the only person they could produce for the Crown Prince. And it was an evening with Gershwin. Part of it was from Porgy and Bess.

[music]

The two singers were Todd Duncan, the original Porgy, and Bess was Camilla Williams, who had a great opera singer, lyric soprano.

TENPAS: This was a big deal event with headline performers. Robert Todd Duncan was one of the first African Americans to sing with a major opera company, and debuted the role of Porgy on Broadway in 1935. In 1936, Duncan led the Porgy and Bess cast at the National Theater in Washington, D.C., and also led a protest that forced the theater to allow the first integrated performance there.

Camilla Williams was the first African American opera singer to receive a regular contract with the New York City opera, where in 1946 she performed as Cio Cio San in Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly.

TENPAS: So, this is sort of the event of the season.

HESS: This was a big thing.

TENPAS: Yeah.

HESS: And certainly staff were not invited to these things at that time. So, I get there and they give you a card as you come in to show who you would go into the dinner with. And my wife and I draw the card, Todd Duncan and Camilla Williams. And of course, we’re thrilled—they’re the most important people there. And we’re standing there and Mamie Eisenhower’s social secretary comes up to me and calls me aside to whisper to me, and to apologize that we had been put together with the two Black entertainers.

TENPAS: Oh.

HESS: And I’m just deflated—

TENPAS: —shocked—

[music]

HESS: —by that. And that’s the moment that it came to me that this was a very segregated world that I was living in, even at that level.

TENPAS: Remember: it was only six years earlier in 1954 that the U.S. Supreme Court struck down school segregation in the landmark Brown v. Board decision—which itself sparked a massive resistance by many white Americans to Black Americans enrolling their children in all-white public schools.

And then in 1957, just the year before Steve came to work in the White House, President Eisenhower ordered U.S. Army airborne troops to ensure that nine Black teenagers in Little Rock could enroll in their high school.

Because the White House staff was so small—32 people at the start of the Eisenhower administration in 1953, growing to about 50 by the end of the decade—Steve had access not only to State Dinners, but to a host of interesting people who worked for the president.

HESS: Yeah. When I got there, there were 50. The ultimately there were 80 who had been on the White House staff in those eight years. Plus military aides. Tiny.

TENPAS: That’s tiny. No wonder you were invited to everything.

HESS: That’s that’s part …Yeah, I think that’s right. That’s part of it. Yeah.

TENPAS: I’m sure you were charming as well.

HESS: No, no, no. Yes, I was charming. And so, I would sit at the staff table every day. The food was good and cheap. I think a sandwich was a dollar 75. And everybody got a napkin ring, a beautiful wooden napkin ring. It said on the top “White House Staff Mess” on the other side, had my name.

[music]

TENPAS: Did you save it?

HESS: Oh, I use it every day.

TENPAS: Oh, you still use it.

HESS1: My napkins are on top of it, yeah. My napkins are just paper napkins now. But that was it.

And then I would be sitting at my table and there would be Jerry Persons, the chief of staff. There would be staff secretary, who was Andy Goodpaster. Andy Goodpaster was the only one who still went on to important things afterwards. Most of these people almost literally retired, but he became NATO commander and then retired. And then when there was a scandal at West Point, he came back into the military to handle West Point. He was pretty special.

The assistant staff secretary, his assistant, was John Eisenhower, the president’s only son. I always thought that if John Eisenhower was somebody else, he would be teaching history in a small Midwestern college. And said he was always where he was because his father was there.

There was Kistiakowsky, the science adviser who’d come from Harvard. Kistiakowsky, was a guy who was one of the great chemists in the world. And when they had to get bombs—this is World War II—into China, he invented a flower that they could bring in, anybody could bring in. They got the flower into a bomb.

TENPAS: Into a bomb?

HESS: Into an explosive.

TENPAS: And this science adviser was the person who invented that?

HESS: Yes. That’s right. So, he was a Harvard professor, George Kistiakowsky. So, there were all sorts of interesting people. There was one guy who handled things mostly that had to do with religious things. He was a Congregationalist minister.

TENPAS: He had a religious adviser back then?

HESS: Well, it wasn’t a religious … people wrote letters like—

TENPAS: —like outreach?

HESS: Yeah, outreach. But he was the original Princeton Tiger because he went to Princeton and his father had real estate in New York. And he had a store that sold uniforms. And he was tired of paying for his son to go to all these games. So, he sent him a tiger [costume]. And he said, here wear you’re tiger [costume] and you can run around that way.

So, everybody had an odd story.

Tom Stephens was the appointment secretary, was an Irishman. He wanted to start a cricket team for us because cricket was a great sport if you had a hangover. And he decided one [day] to wear a brown shoe and a black shoe to see who would discover that he had a brown shoe and black shoe, which nobody did. So, it was fun.

And it was interesting in this regard. These people who had now been there for six, seven, eight years compared to your studies they mostly stayed six years. There were some of them, quite a number of them senior people who stayed all eight years. It wasn’t the old fashioned—

TENPAS: —that’s impressive—

HESS: —two year churn where two years and they go out to get a job as a Washington lobbyist or a commentator on TV. And so, the conversation was very different. It wasn’t like the usual conversation of a luncheon table where you’re talking shop about what you’re talking about, because these people knew their jobs and they didn’t talk that way. But what they tried to talk about was White House talk. White House history talk. They talked about experiences they had had.

TENPAS: No matter its size, Steve says President Eisenhower knew how to run a staff, which is no surprise considering his previous—and still quite recent—experience as Supreme Allied Commander in World War II’s European theater.

HESS: The thing about Eisenhower is he knew how to run things. I don’t know any president that I knew who had that ability. Of course, he reorganized the staff in many ways that continued to today to have a chief of staff, to have a cabinet secretary. This is all things that Eisenhower put in place. He had a system of buffer zones where and he kept people individually separated. And he did it brilliantly.

Jim Haggerty, the press secretary, tells a story that I think totally represents Eisenhower in this picture. They’re discussing the press conference that they’re about to go into. They’re in the Oval Office. The president says to his press secretary, This is what I want to say. Jim Haggerty says, Mr. President, if I say that, they’re going to kill me. The president gets up, he walks around his desk, he pats Jim Haggerty on the shoulder, and he says, “Jim, better you than me.” And that’s the way he had it all adjusted.

TENPAS: President Eisenhower established a White House staff structure that, although much smaller in the 1905s, still exists today.

HESS: The structure that Eisenhower created became the structure of the White House. Before that, under Truman, it was people running around, quite chaotic, not comfortable for Eisenhower when he came in. So, it was Eisenhower who said, there shall be a chief of staff, there shall be a staff secretary. There would be some person in charge of congressional relations. And those are the things that carried forward. So, Eisenhower really created that part of the White House.

[music]

TENPAS: So, there’s a lasting legacy.

HESS: Yes. I think—

TENPAS: —of structure, absolutely—

HESS: —there was in that regard. And that was Eisenhower.

TENPAS: And as noted in episode one, Steve joined the White House staff because of the departure of Sherman Adams, Eisenhower’s tough chief of staff, who had just resigned due to scandal, which smoothed the way for Steve to accompany Mac Moos to the White House. And remember, this happened in the seventh year of the administration, a bit of timing that also had fortuitous consequences for Steve. So … Sherman Adams.

HESS: I did not admire him. He was a tough guy. And that’s exactly how the president wanted his chief of staff to be as it had been in Europe. And that was Sherman Adams. But he was replaced, now we’re talking about the last two years of the administration, by a man named Wilton Persons, which is sort of interesting. There’s a well-known book out now on chiefs of staff. And he’s not even mentioned.

TENPAS: Oh, wow.

HESS: Yeah. Isn’t that funny? Uh, and he was there for two plus years at the end of the administration. He was called Jerry Persons. Jerry Persons in World War II had been the Pentagon’s lobbyist with the Congress. So, he was not a hard-nosed politician, even though he was by now a major general.

TENPAS: And recall from the previous episode when Steve said that Jerry Persons was, quote, “very easygoing” and “wanted people to be happy.”

HESS: And also when he took over at the end of the administration, it was really not necessary to be that tough anymore. Everybody knew their job, they’d been doing it for seven years, and so he had a much looser rein.

And I was the beneficiary of that. But more than that for some reason, he was awfully nice to me. He sent me little notes. Congratulations on other work. He gave me all sorts of assignments that weren’t under speech writing. So, I appreciated that.

[music]

And so, the White House is a place where lots of people remember a rough time and a rough atmosphere, and mine was really very soft and very comfortable.

TENPAS: One thing Steve noticed in Eisenhower’s White House that had not changed, but has since been transformed by the growth in the size and professionalism of the White House staff, was the role of Cabinet secretaries in the policy process. Even as a junior speechwriter, Steve had unprecedented access to these high-level officials.

HESS: Oh, yes, I was very involved with Cabinet secretaries because that was the nature of the White House staff under Eisenhower, it was entirely different as you see it now, and you’ve written about it, where the White House keeps growing bigger and bigger, because there’s now a White House aide on energy and a White House aide on this and a White House aide …

At that time, it was all done through the Cabinet officers. We had a Cabinet secretary, and the job of the Cabinet secretary was to keep it on track. And the job of Sherman Adams, who everybody thought was running policy, he wasn’t running policy. What he was doing is if the secretary of labor had a fight with the secretary of commerce, he would call them in and have them argue till they had worked out their plans. That was what the White House did.

The White House did maybe one or two major policies, like the great policy it did on the highway system of the United States. But typically, the policies came from the departments. They were carefully considered at a Cabinet meeting because the president got his information, liked his information, from listening. Very different from Nixon, who liked his information from reading, which got him in a lot of trouble eventually.

So, they would talk about these things. And the president generally, if they agreed in front of him, would say, okay, that’s policy. And then it would come down. And then we would have a meeting of the assistant secretaries, which I often attended, in which, okay, this is what they decided, This is what you have to do. And then the lobbying was generally done by the departments for their own pieces of legislation.

[music]

There were five I think, ultimately five lobbyists on the White House staff. But generally they called the back each week and said, okay, what happened this week? What did you do? So, it was a very, very different system.

TENPAS: As you’ll learn in this series, Steve Hess worked in the White House in two presidential administrations, and with five presidents over the course of his career. I asked him to reflect on his time in the Eisenhower White House, and in his answer he made an interesting connection to the next time he was in the White House three presidents later.

…

TENPAS: In looking back, would you say that those two years were the best? Was it all downhill after that? Was that the best part of your career?

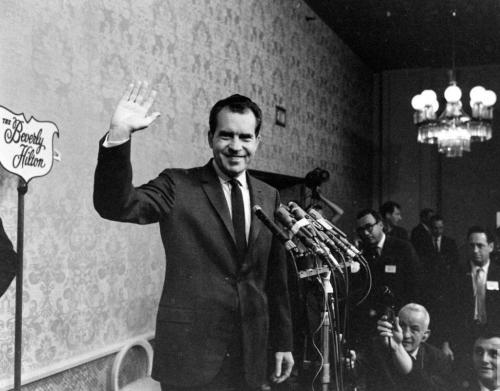

HESS: My career? Oh, I guess. I don’t know. I suppose it was the most fun. I did a lot of things that were tense, running things that didn’t go that that way. I felt so comfortable. Gosh, it certainly wasn’t that way on Nixon’s staff.

In other words, I was on the White House staff itself twice. And it was sort of interesting because once it was the beginning of an administration, with Nixon, once it was the end of administration. And it was quite clear from that, that it’s different.

And in fact, I did write ultimately an essay that dealt with what the White House looks to the president year by year. This is year one, Mr. President, this is your presidency in year two.

So, I was I was there, again, with Nixon where everything was going haywire. At the end with Eisenhower, where now it was really very smooth and comfortable.

TENPAS: Do you think that was possibly a reflection of the leadership as opposed to the timing?

HESS: I think a lot has to do with the leadership. We’re of an interesting generation, you and I, in political science. Before that, the books we read were on President Coolidge or President Harding or so forth and so on. And we did a lot on how the system actually worked and the importance of that, doing that.

Well, the truth of the matter is I saw all these things because not only was I on two White House staffs, but I got involved with three other presidents. How much it really made a difference by who the president was. That really was it. I mean, we know that, just look at Donald Trump, if you want.

But the idea that … what really made a difference, as we the two of us did a lot of writing of that about, was how they organized the White House for congressional relations. Oh, yes, these were all important. But what really made a difference was the presidents. And this, of course, ultimately becomes important part of this podcast when we see the difference between Eisenhower and Nixon.

[music]

TENPAS: So, I wondered, what would Steve say about how Eisenhower was thought of in the early ‘60s, just after his presidency, compared to how he’s regarded today?

HESS: This is very strange. History now treats him well. It didn’t treat him well at all when he left the presidency. Arthur Schlesinger, Senior, had a big poll, mostly of academics, and they rated Eisenhower almost above the non-existent presidents like James Buchanan, he was so low on their list.

Then years later, his son, Arthur Schlesinger, Junior, did the same thing. And Eisenhower was up almost to the position of the really great presidents—Washington, Lincoln, Jefferson, and so forth. So, he was in there at about five, four or five. Amazing. Same person. But history had different views of him at different times.

TENPAS: Over time, you tend to look better, you age better, it’s sort of like wine a little bit.

HESS: Life is better. You look back and say, Hey, wow, you know, I was pretty comfortable there at the end of the Eisenhower administration. Now we’ve gone through three wars, we’re not feeling comfortable at all. Let’s rate the president who we think was responsible for those wars.

TENPAS: Right, right. And it also may depend on your successor. So, for instance, President George W. Bush was not thought to be the greatest president, but then the next Republican president is Trump. So, people are saying, oh, George W. Bush wasn’t so bad.

[music]

HESS: That’s true.

TENPAS: And that’s all for our journey into Steve Hess’s time on the staff of the Eisenhower White House. You can learn more about all of it in his book Bit Player, from the Brookings Institution Press.

In our next episode, we find Steve in the 1960s, first during the 1960 presidential campaign between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, and then later between presidential administrations in which he served. But just like he joined the Eisenhower administration through a series of lucky breaks, he enters the orbit of former vice president Richard Nixon almost by accident.

[music]

Thank you for listening to Quite by Accident, a podcast from the Brookings Podcast Network. I’m Katie Dunn Tenpas at Brookings and the University of Virginia.

I’d like to thank Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews, senior producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video editor; Colin Cruickshank, videographer; Katie Merris, who designed the cover art; and Tracy Viselli and Adelle Patten from Governance Studies.

A very special thanks to my dear friend and colleague Steve Hess.

Additional support for the podcast comes from colleagues in Governance Studies and the Office of Communications at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastEpisode 3: State dinners, White House staff, and farewell to Eisenhower

December 14, 2023

Listen on

Quite By Accident Podcast