Twenty years on from the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) it is timely to assess how the East Asian region is placed to manage and mitigate risks of economic crises. We imagine a scenario where one of the emerging economies of Southeast Asia faces risks of financial crisis from internal and external sources. Given gaps in the global and regional safety net, such a scenario would raise difficult choices for the country, its neighbors, and key regional donors. My new working paper is about widening available choices so there can be more confidence that an emerging crisis will be nipped in the bud.

Such a scenario could look like this:

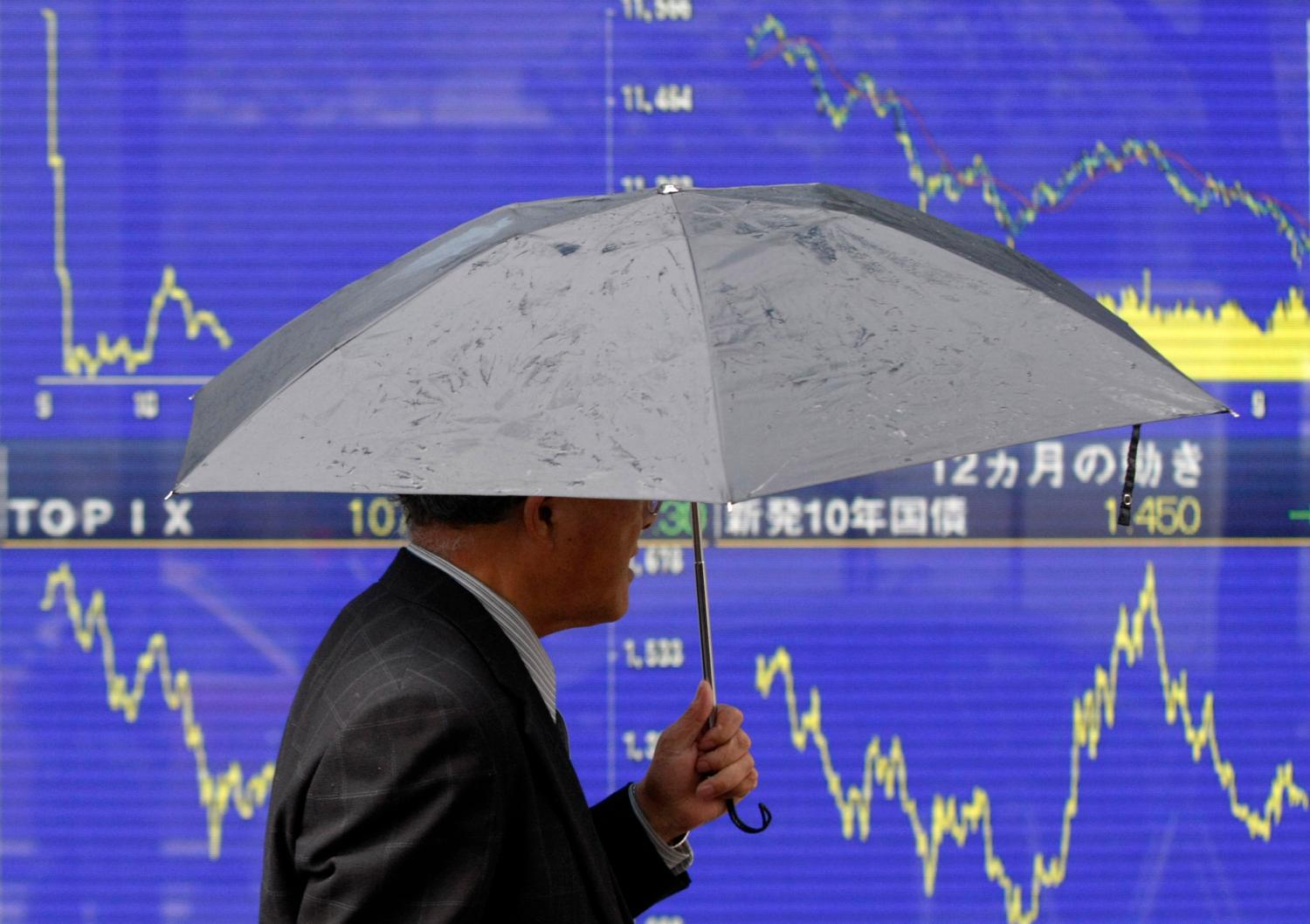

It is a Friday night sometime in a few years from now. Pressure has been building in currency and bond markets for several Southeast Asian economies. One large ASEAN country has contacted other capitals in the region, concerned that it will face a serious market disruption when markets open early the next week. The economy has been well-performing and policies are sound; but, markets have been reacting to tighter financial conditions in the U.S., producing a “risk-off” event. Also, capital inflows have stopped abruptly, and the tide is going out. This has come at a time when financial instability and falling demand from China has put pressure on macroeconomic settings. Talk of another Asian financial crisis has contributed to early signs of a run on a couple of the country’s financial institutions.

The country has been meeting with IMF staff but is nervous about the domestic political consequences of approaching the Fund for support. The authorities are seeking bilateral support from several regional partners, including China, Japan, and Australia. But China is facing capital-account pressures of its own, Japan has very little macroeconomic room to maneuver, and commodity price falls are posing challenges for Australia’s macroeconomic management.

Parallel discussions are occurring about whether to trigger the regional foreign currency swap agreement known as the Chiang Mai Initiative Mutualization (CMIM), but uncertainty about whether this mechanism is ready for use is causing hesitation. Other ASEAN participants are carefully watching for signs of contagion, and nervous that they may need to use their foreign reserves to manage their own circumstances.

There is a hard weekend of decisionmaking ahead for ministers and officials in many capitals. It involves hurried calls across time zones, decisionmaking under a fog of uncertainty, and consideration of economic, budgetary and foreign policy choices. Regional swap arrangements will be put to the test and doubts about IMF involvement may constrain the amounts available under these arrangements. Risks of contagion could reduce some participants’ contributions.

Regional donors may well agree to provide support, although under uncomfortable circumstances. For example, there might not be IMF “cover” for bilateral financing. Also, assessments being made on the run with other donors, each with various interests and perspectives, could delay a financing package. And the scale of support might not be enough, or delivered too late to prevent a panic, resulting in economic and social disruption—that could be avoided.

This hypothetical scenario highlights that East Asia faces a very different circumstance than it did in the AFC 20 years ago. In particular, the region faces greater risk of common and systemic shocks. This suggests the region should take a more deliberate, coordinated approach to managing regional risks, including strategic use of its networks to maximize its impact in international forums. It should prepare to present a strong common front in the G-20 in a crisis. The region should also seek to close gaps in financial safety net arrangements, including: (a) taking action to ensure the IMF is an early resort in a crisis, given the likely importance of access to global resources in a regional crisis; (b) improving the speed with which resources can be delivered in a liquidity crisis; (c) enhancing links between the IMF and CMIM, and between both of these and proliferating bilateral arrangements; and (d) over the medium term, assuring the quantum of crisis resources available particularly in the IMF.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).