In 2021, Democrats ended the 10-year earmark moratorium. Earmarks, occasionally referred to as “pork,” are small grants to programs and projects in congressional districts. House Republicans were skeptical of bringing back earmarks, though they recently voted to keep earmarks for the 118th Congress. We do not yet know if Republicans will change the earmarking process. However, we find that the parties have a fundamentally different approach to representation when it comes to their earmark requests. By analyzing data in 2021, we do know that House Democrats and Republicans used earmarks to accomplish very different goals and framed the projects funded by them in different ways. Democrats adopt a transactional or distributional approach to representation and promote policies that appeal to their big-tent constituency. Republicans adopt a more symbolic approach, emphasizing American imagery and values.

In our new paper “Partisan Asymmetries in Earmark Representation,” we analyze written justifications to measure how members approach representing their constituents. Under rules first introduced in 2021, members of Congress can request up to ten earmarks in each appropriations cycle. With each of these requests, the members must submit a written justification for why their project is a good use of taxpayer dollars. These written justifications give us an opportunity to see what policy topics are in each earmark, who the earmark is for, and how the funds will have a demonstrable impact on their constituents. We performed a content analysis of all 3,007 of these justifications and found clear partisan differences in the earmarking process.

“At the individual member level, Republicans requested over $20 million more than Democrats.”

Because earmarks by their very nature spend government money, we might expect Democrats to use the earmarking process more. But that supposition is just partially correct. On average, in the 117th Congress Democratic representatives requested two more earmarks than their Republican colleagues at a ratio of about ten-to-eight. But looking at just the number of earmarks requested undersells the partisan differences in earmarking behavior. When we change our unit of analysis to the earmark amount, we see that Republicans asked for $3 million more per earmark than Democrats ($4.7 million for Republicans; $1.7 million for Democrats). At the individual member level, Republicans requested over $20 million more than Democrats.

“The content in Democratic earmarks, however, are more want-based entities and less expensive than physical infrastructure projects.”

At first glance these numbers are jarring, especially given the previous Republican commitments to cutting budgets and eliminating wasteful spending. But looking at the policy content of the earmark requests explains Republicans’ large-dollar requests. The “local infrastructure” projects requested by Republicans are equal parts a need-based entity in their districts (everyone needs a good road and bridge) and expensive. The content in Democratic earmarks, however, are more want-based entities and less expensive than physical infrastructure projects.

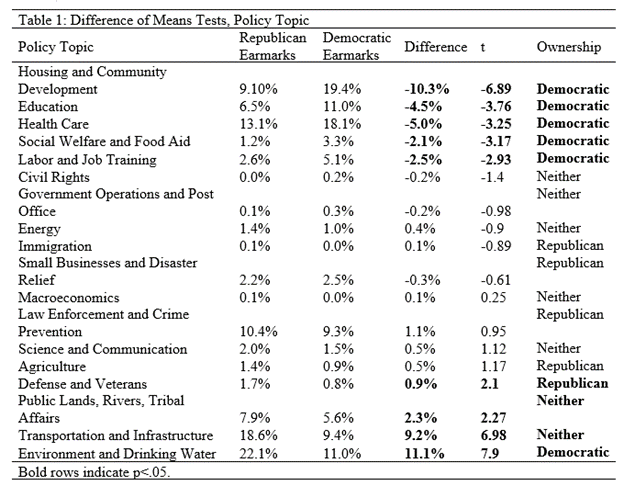

Now that earmarks are staying around for the 118th Congress, we can speculate on two possible outcomes for the future of earmarks. One possibility is that earmarking behavior in the 118th Congress is the same as it was in the 117th. We’ve already addressed a few dimensions of the earmark process. But in our paper, we also test whether earmark representation is shaped by conventional understandings of partisan issue ownership (see Table 1). Issues “owned” by Republicans are high-level: defense, the economy, and immigration. Earmarks are not well-equipped to deal with these issues, as they operate on a district level. Democratic owned issues, on the other hand, are very well suited for earmarks: social welfare, education, and community development. We find that Democrats requested significantly more earmarks with policy topics they owned compared to Republicans. Republicans used earmarks for the large infrastructure projects for which they could claim credit.

If in the 118th Congress the behavior stays the same, we would expect Republicans to request much more money from each earmark for their infrastructure projects than their Democratic colleagues, even if they continue to request fewer earmarks in the aggregate. The trend seen throughout this process continues; what Republicans request in an earmark is fundamentally different from what Democrats request.

But a second, and more likely, possibility, is that earmarking behavior shifts in response to Republicans controlling the appropriations process. This means Republicans will start to request more earmarks than they did in the 117th Congress, and Democrats will request fewer. It also means that Republicans will begin to utilize earmarks as a tool for representation and start to request earmarks that target their core voting blocs.

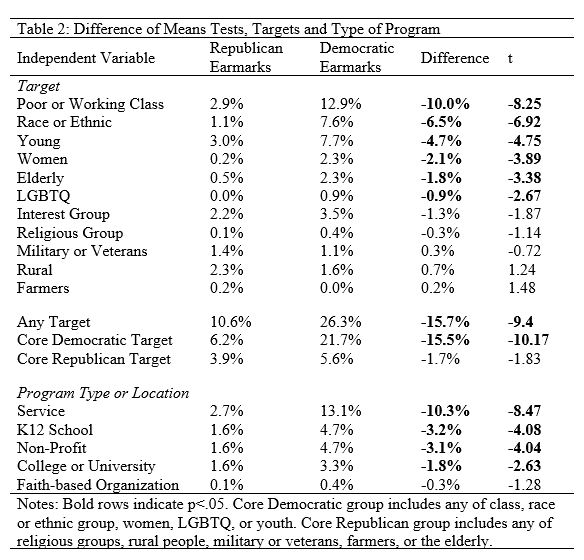

In our research, we show how Democrats used earmarks as a tool for representation in this way. We group the target populations referenced in the justification letters required to accompany requests by the House Appropriations Committee into core Democratic and core Republican voting blocs (see Table 2). We define a core Democratic target as any reference in an earmark justification to class, race, women, ethnic group, LGBTQ persons or youth. A core Republican target is defined as a reference to religious groups, rural communities, military personnel, farmers, or the elderly. Democrats referenced a core target group in 22% of their earmarks in the 117th Congress. Republicans referenced a core target group in only 4% of their earmarks. These percentages align with the policy topics contained in an earmark justification as well, as the large infrastructure projects requested by Republicans are less likely to be targeted towards a key constituent group. So as Republicans alter their earmarking behavior in response to their new control of the House Appropriations Committee, expect to see more earmarks for fewer dollars, with an increased focus on projects that benefit their core target group.

The ten-year gap between earmarking cycles means scholars can approach studying these appropriation tools with fresh eyes in a contemporary context. Earmarks offer a new opportunity to see tangible evidence of the federal government “working” at the local level. If they continue to be allowed in the next congress, more earmark justifications will roll in during the next appropriations cycle. It will be interesting to see how a Republican-controlled House of Representatives will use this tool to benefit their constituents; and how Democrats, now serving in the minority, will adjust their behavior.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Earmarks are back: How Democrats and Republicans differ

January 12, 2023