If you believe this week’s headlines, math and reading scores are on the slide. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores for 12th graders just released show falls of 1 point in both average math and reading scores between 2013 and 2015. And since 2005, both the math and reading scores have essentially been flat.

Cue hand-wringing about America’s declining educational status. But let’s pause for a moment. Regular readers of this blog may remember that last July, I showed how changes in the composition of a population over time can lead to faulty conclusions based on average trends. In fact, the trend of the whole population can be quite different from (or even the opposite of) the trend of the constituent parts, a statistical phenomenon known as Simpson’s paradox.

Diversity explains lower long-run average scores

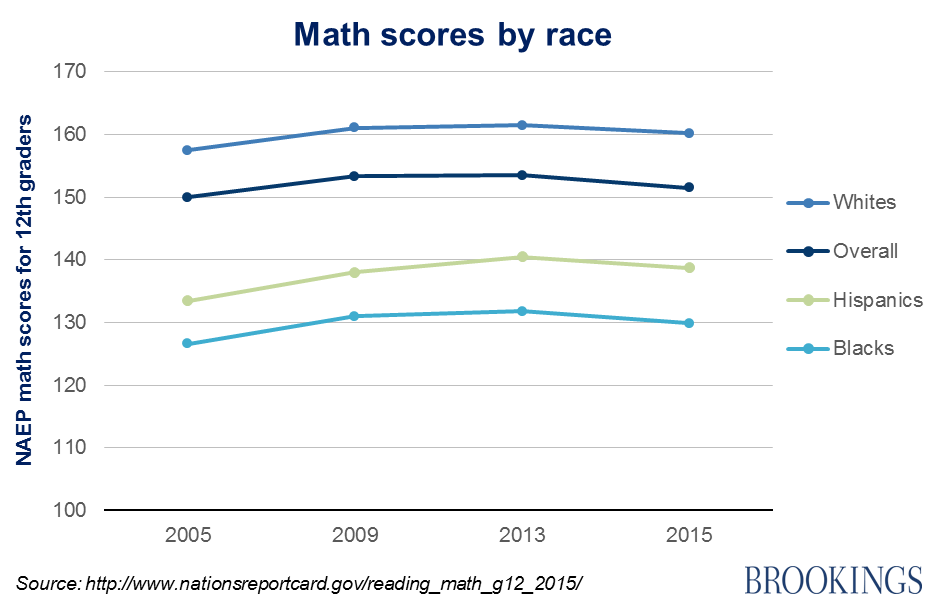

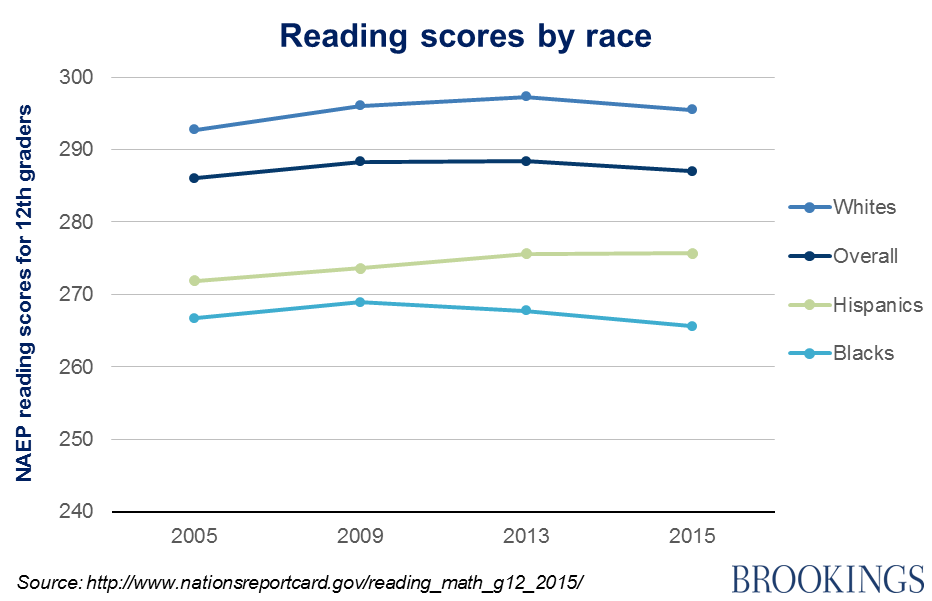

Given this week’s flurry, it is worth revisiting this question. First, let’s look at the apparent long-term stagnation. Between 2005 and 2015, average NAEP scores rose by just 1.5 points in math and 1.0 points in reading—not statistically significant in either case. But when we look at scores by race and ethnicity, we see a different pattern. Scores for students in nearly all racial categories for both math and reading showed statistically significant improvements over the decade (the only exception was a non-significant 1-point decline in reading for Blacks):

Q. What’s going on here? A. Simpson’s paradox. The apparent stagnation in the whole population is actually the result of a large increase in the share of Hispanic 12th graders, who score lower on average.

Recent declines may result from more students staying in high school

What about the recent dip from 2013? This cannot be the result of racial composition changes, since there is a general fall in scores across racial categories. But we should not rule out other compositional explanations: for example, increased high school graduation rates, especially for Blacks and Hispanics. Good news, of course (though as others have noted, some of these gains may have come from growth in alternative programs that may not be as academically rigorous).

More students in high school means more students taking the NAEP exam in 12th grade. Those who may have dropped out in the past but are in school today are likely to have lower scores. So it is quite possible that the overall decline in NAEP scores between 2013 and 2015 is also due to compositional changes, in this case in the composition of those remaining in high school.

All told, you probably want to take this information with more than a grain of salt when considering the popular conclusion that educational standards are slipping.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Don’t believe the headlines: Educational standards are not collapsing

April 28, 2016