This post is Part 2 in a three-part series on democratic decline in the United States. To learn more, see the first post in this series, “Four Things to Know about Democratic Erosion” and the full report, “Understanding democratic decline in the United States.”

Last week, the Supreme Court heard another case about whether a state’s new maps constitute racially discriminatory gerrymandering, and a federal judge barred former president Trump from attacking witnesses, prosecutors and court staff involved with his federal trial for election subversion. It is a good time to reflect on how the states and the courts are ensuring (or failing to ensure) free and fair elections in the United States. Unfortunately, strategic manipulation has become a recurring feature of U.S. elections, and there are good reasons to doubt whether the courts will adequately protect voting rights as we head into the 2024 election season.

Distinct from “voter fraud,” which is almost non-existent in the United States, election manipulation includes election procedures that make it harder to vote (like inadequate polling facilities) or that reduce the opposing party’s representation (like gerrymandering). These kinds of maneuvers have become increasingly common and increasingly extreme in recent years — but only in some states.

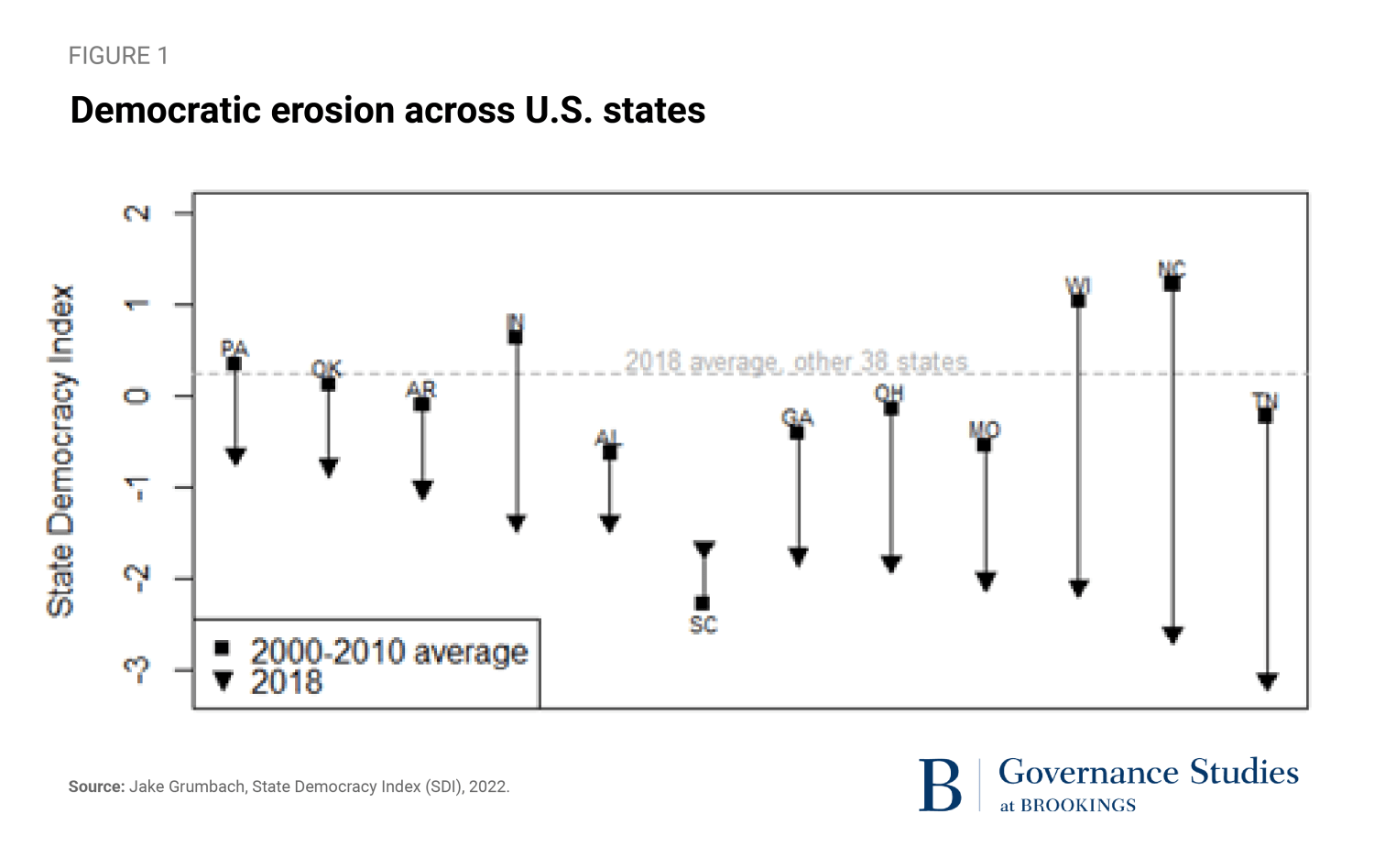

Political scientist Jake Grumbach has developed the most comprehensive and rigorous measure of state-level electoral democracy, the State Democracy Index (SDI), which takes account of factors like polling place wait times, red tape voter registration procedures, and gerrymandering. The SDI quantifies the divergence occurring between U.S. states. In 2018, 17 states had a higher SDI than they did during the period from 2000 to 2010, indicating a stronger democracy in those states. The other states, however, have seen their SDI decline — some by a very substantial margin.

Figure 1 shows the 12 states at the bottom of the SDI. Almost all the states scoring poorly in 2018 have seen very large declines since 2010; these weak-democracy states have weakened recently and drastically.

At least as important as the magnitude of the decline is the reason for this erosion of electoral democracy. Grumbach finds that Republican control of state government “dramatically reduces states’ democratic performance.” Grumbach’s finding confirms earlier research identifying the association between GOP control and the adoption of measures to restrict access to the ballot. The declining commitment to democracy is occurring both at an elite level and in the base of the party; survey research demonstrates that “ethnic antagonism” has eroded “Republicans’ commitment to democracy.”

Since 2018, the fundamental political dynamics that led to the erosion of U.S. democracy remain unchanged. Trump remains the front-runner in the 2024 Republican presidential primary, and most of his opponents for the nomination have vowed to support him even if he is convicted of election-related crimes. There are a larger number of election deniers in Congress today than in 2021 and about two-thirds of Republican voters still deny that Biden legitimately won the 2020 election. The politicization of election administration has continued; since 2020, state legislatures have passed dozens of laws to increase partisan control over election administration and vote counting procedures. As long as a major political party remains uncommitted to accepting legitimate electoral defeat, democracy cannot be reasonably described as secure.

The primary backstop against state legislation that threatens voting rights is the court system. Judicial decision-making has never met the ideal of perfect impartiality, but conservatives have been unusually successful in appointing judges to the appeals courts and the Supreme Court has become exceptionally conservative and partisan in recent years,1 while bypassing standard procedures, precedents, and norms that had previously governed the Court.2 Today, most Americans — including most Democrats and most Republicans — believe the Court is motivated primarily by politics, rather than by the law.

The Supreme Court has also narrowed the scope of voting rights protections and expanded its interventions in elections as they occur. Starting in 2013, the Court began cutting back the 1965 Voting Rights Act that outlawed racially discriminatory voting practices,3 allowing states to implement procedures previously barred as discriminatory. In 2020, the Supreme Court intervened to block several emergency efforts intended to make voting easier during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, the Court took the unusual step of staying an injunction against Alabama’s redistricting map that a lower court found discriminatory, effectively ensuring that the map would be in place for the election. The reasoning behind this decision is particularly opaque given that the Supreme Court has since agreed that the map is, indeed, discriminatory. In addition, the Court has expanded its authority in the adjudication of disputed elections.

Given the long-term trends in the states, and these recent court precedents, there is good reason for concern going into what will surely be a hotly contested 2024 election. Though there have been legal consequences for many of those who participated in the 2020 election subversion efforts, and though the 2022 elections occurred without major incident, Americans should remain vigilant in the face of ongoing threats to election integrity.

-

Footnotes

- Thomson-DeVeaux, A. and Bronner, L. “The Supreme Court’s Partisan Divide Hasn’t Been This Sharp in Generations.” FiveThirtyEight. July 5, 2022. Jessee, S., Malhotra, N. and Sen, M. “The Supreme Court is Now Operation Outside of American Public Opinion.” Politico. July 19, 2022. Lazarus, S. “How to rein in partisan Supreme Court justices,” Brookings. March 23, 2022. On the role of the Federalist Society in reshaping the ideological makeup of the judiciary, see Toobin, J. “The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court,” The New Yorker, April 10, 2017. Green, E. “How the Federalist Society Won,” The New Yorker, July 24, 2022.

- Lazarus, S. “How to rein in partisan Supreme Court justices,” Brookings. March 23, 2022. Totenberg, N. “The Supreme Court and ‘The Shadow Docket,’” NPR, May 22, 2023.

- In 2013, in Shelby v. Holder, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the formula used to apply the “preclearance” provision of the VRA, which required localities with a history of discrimination to have any changes in voting procedures approved in advance by a federal court or the Department of Justice. Two other decisions have narrowed the interpretation of Section 2 of the VRA, which outlaws discriminatory election practices.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Democratic decline in the United States: Strategic manipulation of elections

October 23, 2023