The European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) has crossed a regulatory Rubicon. It is an advance that moves away from industrial-style regulation by micromanagement to a new digital model focused on identifying marketplace outcomes.

In 49 B.C.E., Julius Caesar, then commander of Roman forces in Gaul, marched his army across the northern border of Italy at the Rubicon River to challenge the leadership of the Republic itself. “The die is cast,” (Alea iacta est) he reportedly uttered upon making that fateful decision.

That the die is cast is an appropriate inscription for the digital regulatory actions of the European Union (EU). Like Caesar’s decision to proceed, its modern echo will reshape governmental processes overseeing the technology that is reshaping the world.1

The new digital reality

For the last several decades, governments around the world have looked to their industrial era statutes—especially antitrust statutes—to try to deal with the aggressively accumulating power of companies operating digital platforms. Among the most aggressive in this effort to make old statutes work in a new era was the European Union (EU). This was especially true in the EU’s use of competition law to try to reset the practices of Big Tech.

After years of litigation, the inability of this strategy to resolve digital marketplace problems arguably led European legislators to replace industrial era concepts with a series of new statutes. The DMA focused on marketplace choice, the Digital Services Act (DSA) addressed internet content, the Data Act (DA) established rules for the use of digital information. Most recently, the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) established risk-based expectations for artificial intelligence (AI).

Such initiatives are necessary because the digital economy is simply different from the industrial economy. Digital assets are different (soft vs. hard); their behavior is different (rivalrous vs. non-rivalrous, iterative vs. exhaustive); and thus, the behavior of markets using the assets is different (network effects vs. scope and scale).

Industrial era oversight was designed to offset the power of scope and scale economics with counterbalancing regulatory authority. Competition law put typically ex post antitrust boundaries around those scope and scale economies.2 Regulatory policies, typically ex ante, stipulated the nuts-and-bolts practices such as technical standards and interoperability while simultaneously managing marketplace effects by directing corporate behavior.

Digital platform power has outmatched the old regulatory model. By interacting with billions of customers daily to collect their personal information and using that data to influence the activities of these same people, the barons of the digital age have achieved what industrial barons could only have dreamed of: an asset that is incrementally almost cost free to collect and hoard, and for which monopoly rents can be charged.

The EU’s attempt to use litigation to affect the behavior of digital companies has been informative. The slowness of the judicial process hinders its ability to keep pace with technological change. EC-imposed remedies—typically fines—end up as gnat bites to deep-pocketed corporations. Rather than altering their behavior, injunctions aimed at specific past behavior have allowed the companies to reproduce the same anti-competitive effects through other conduct. Add to this the asymmetry between a government litigator with limited funds and a digital platform company with deep pockets in both funding as well as the data necessary for the litigation. It is not surprising that judicial vehicles have proven to be problematic.

The power of digital economy network effects has overwhelmed industrial economy assumptions, and with that efforts to increase competition among firms targeting a particular market. The result has tended toward a winner-take-all reality. In place of multiple effective competitors, a single dominant victor emerges—a victor that also can apply profits from that dominance to combat potential new competitors.

The focus of the DMA, therefore, is to open markets through another mechanism: the stipulation of acceptable marketplace outcomes overseen by regulatory enforcement. In response to the lack of competition in specific digital markets, the DMA seeks through regulation to create market contestability.

While the path to such competition does not displace antitrust policy, the EU determined that old regulatory tools needed to be accompanied by new regulatory concepts. The DMA was the result. In lieu of the old regulatory model of, “We will tell you how to run your business so that public interest goals are achieved,” the DMA’s approach is, “We will identify the desired public interest goals and enforce your efforts to achieve them.” It is a nuanced difference, but a watershed from typical regulatory behavior.

How the DMA works

The DMA establishes multiple new regulatory concepts that differentiate it from industrial oversight models:

- New goal – Whereas traditional regulatory policy, especially in the United States, evolved to focus on the effect of corporate behavior on consumers (especially price), the DMA has prioritized enabling other businesses to potentially offer competitive choices to those consumers.

- New measurement – To facilitate such competition, the DMA establishes two new measurements: “contestability,” meaning the promotion of entry into markets, and “fairness,” such as not preferencing its own products or services over those of others using the platform;

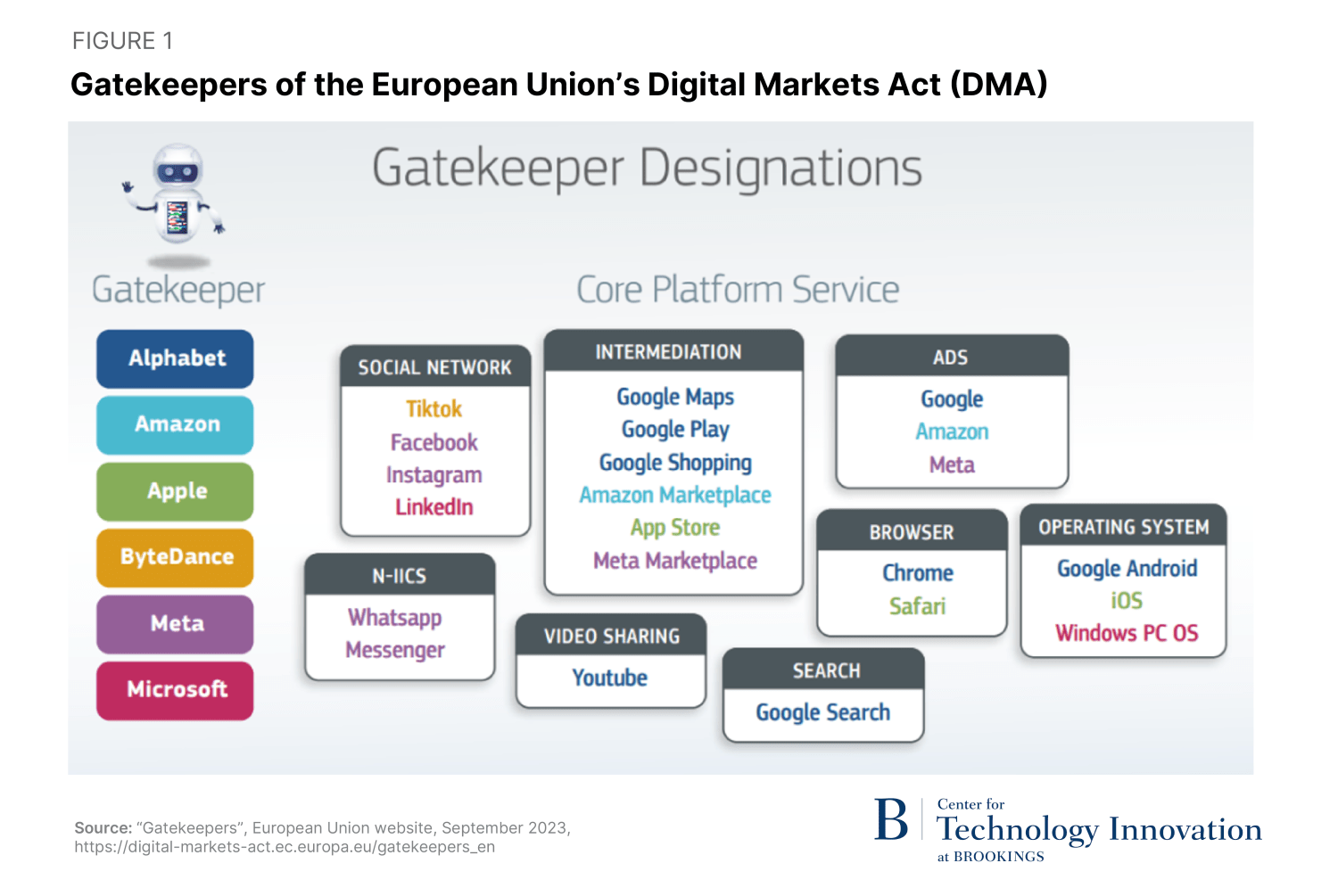

- New target – The DMA focuses on six large companies deemed to be “gatekeepers” (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft) and 22 of their “core platform services” having significant European market impact (Figure 1);

- New model – Rather than putting the burden on the government to prove a behavior unacceptable, the DMA puts the burden on the companies to demonstrate how their practices promote contestability and fairness;

- New expectations – In lieu of regulatory micromanagement, the DMA establishes the expectation of self-executing compliance without stipulating the precise company behavior to achieve this goal. Failure to meaningfully deliver on this self- execution triggers regulatory compliance penalties up to 10% of a company’s gross revenue.

These changes in regulatory practice establish public interest expectations for the effects of corporate behavior rather than dictating that behavior in detail.

The new regulatory paradigm

While the DMA contains some vestiges of old-style behavioral rules (e.g., prohibiting cross-platform data sharing), its revolution comes in the areas where it eschews dictating with precision how a company will act in favor of specifying that the desired effects of corporate behavior should be marketplace contestability and fairness. Having established such expectations, it becomes the responsibility of the company to deliver on those anticipated effects or face the consequences. For example, the DMA dictates interoperability for certain digital services but does not specify how companies should achieve this if the means satisfy the metrics of contestability and fairness.

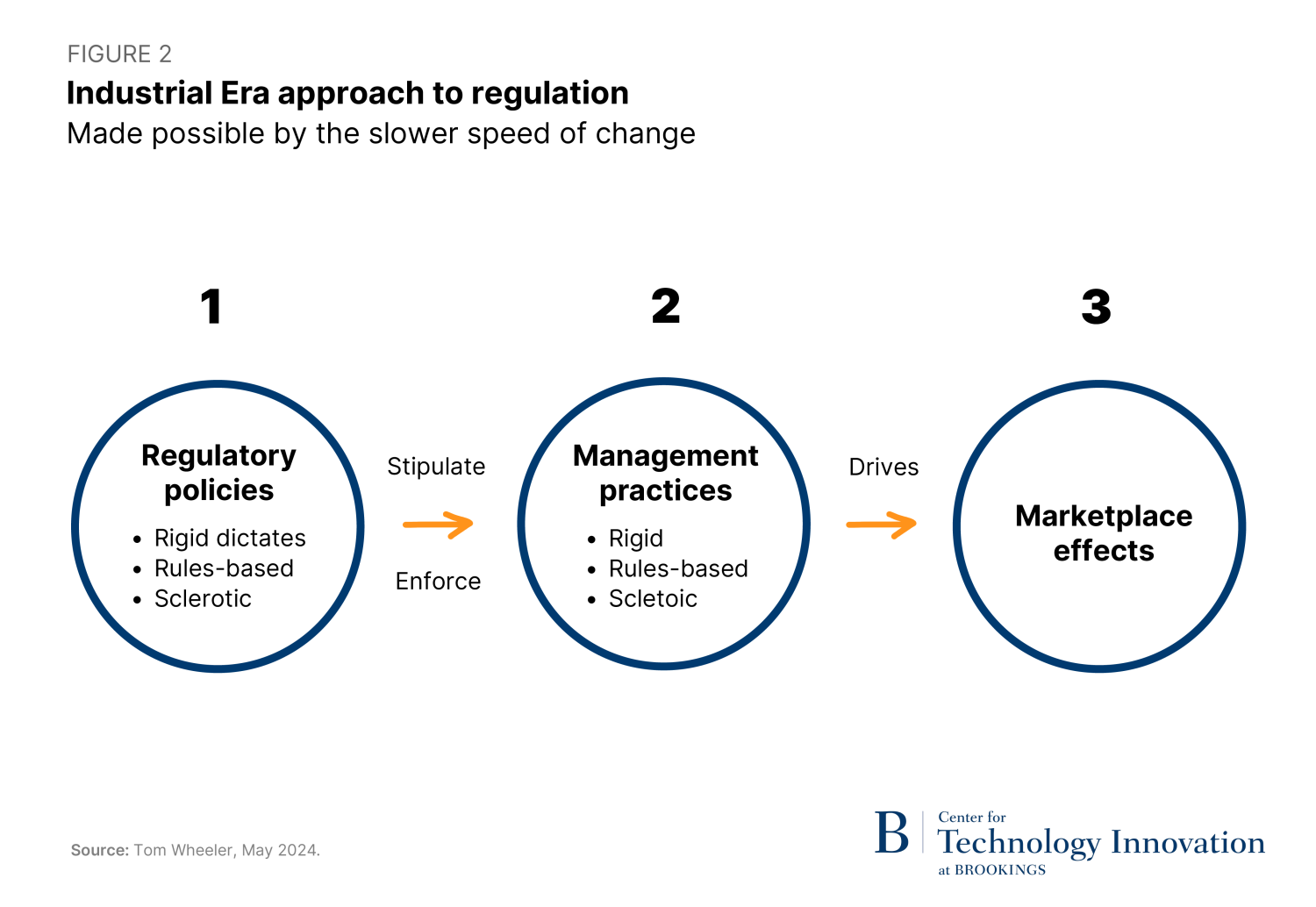

This nuanced policy adjustment—shifting from “how” to “what” —is a huge reversal from regulation that sought to define marketplace effects by rigidly stipulating corporate behavior. Such industrial era regulation (Figure 2) copied the so-called “scientific management” that dictated from the top-down everything from corporate procedures to production line practices. Both models— corporate as well as regulatory —were aided by the relative slowness of both technological and marketplace change.

The rapid pace of digital era technology and markets has rendered the industrial era approach overly rigid and sclerotic. Not only did regulation tend to await a sufficient demonstration of harm, but also its explicit operational dictates were arguably counterproductive to innovation and investment. Just as regulatory models in the industrial period cloned the management models of the era, the DMA attempts to embrace digital management built on risk-based prioritization to keep up with change, accompanied by agile structures to respond to identified risks.

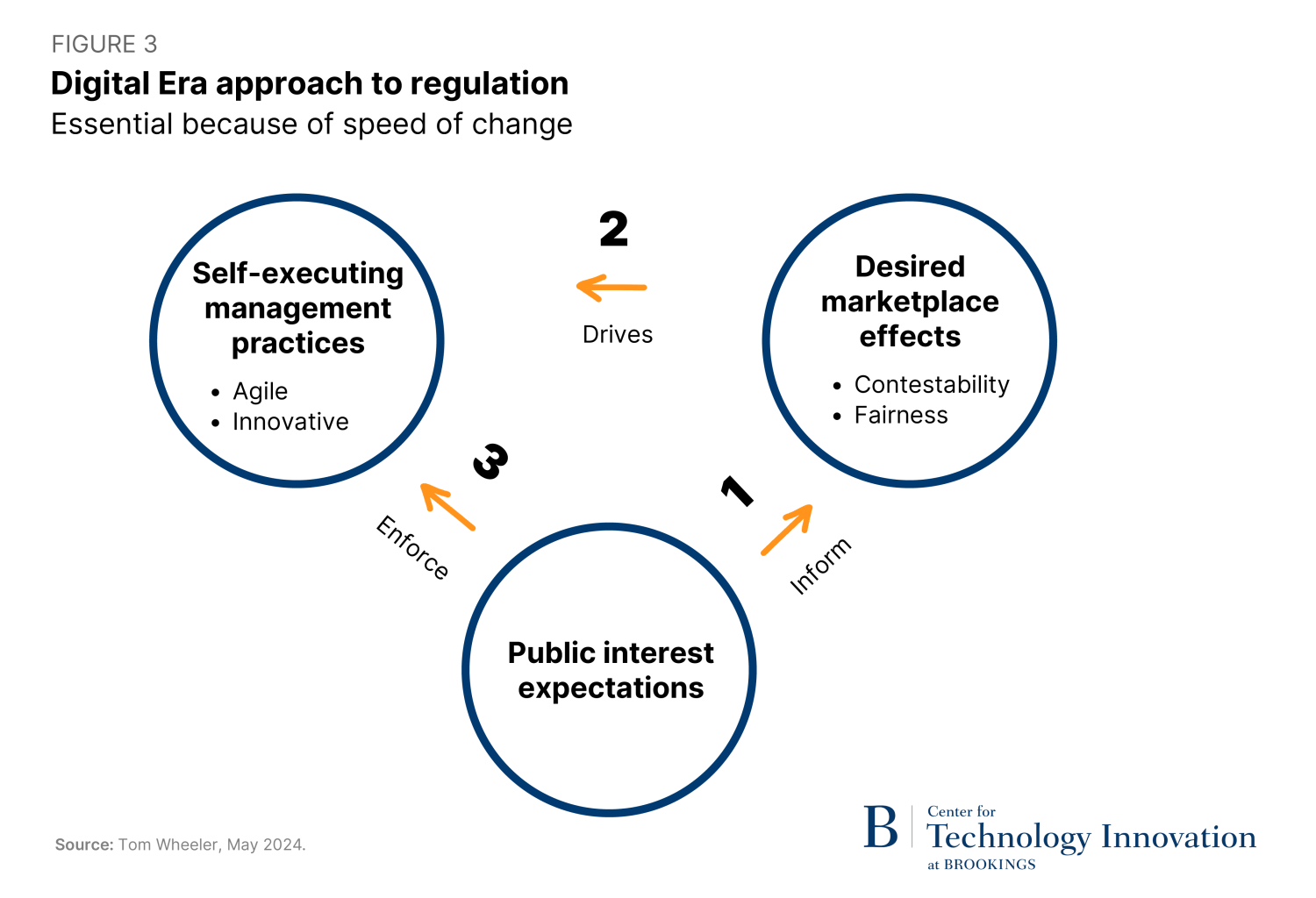

The model being pursued by the EU moves in this more agile, effects-based direction (Figure 3). After identifying the desired marketplace outcomes, the new model works backward to the enforceable expectation that management practices will deliver those results. By moving away from regulatory micromanagement, the model has the added benefit of being more friendly to innovation.

The DMA’s refocusing of regulatory activity from dictating corporate decisions to the establishment of an enforceable expectation that those corporate decisions will promote contestability and fairness is a Rubicon-like decision that redefines the digital regulatory paradigm.

Regulatory strategy meets gatekeeper tactics

After Caesar crossed the Rubicon, he was confronted by the forces of the old guard. So it will be with the implementation of the DMA. It is insufficient to simply have a bold strategy. The ultimate outcome will be determined by the tactical skirmishes and battles that follow.

While the European Parliament strategically crossed the regulatory Rubicon, the outcome of that decision will be tactically determined by the struggles between the regulator, the European Commission, and the affected companies. Ultimately, the outcome will be adjudicated by European courts.

It appears that both regulator and regulated are preparing for a long campaign.

The opening skirmishes in this struggle were the March 7 filings of the companies’ first compliance reports with the Commission. Some companies changed their practices and said their new operations satisfied the DMA requirements of contestability and fairness. Not surprisingly, many gatekeepers generally asserted they were already in compliance with the DMA. The Commission, also not surprisingly, had a different opinion. As of this writing, the Commission has responded to the assertions of Alphabet, Apple, and Meta by launching non-compliance investigations. In addition, it ordered the three companies, as well as Amazon and Microsoft, to preserve evidence that could be potentially relevant to further investigations.

Revolutions do not retreat

The decisions of the world’s second largest economic block can ultimately have implications around the world. The new digital regulatory paradigm will not only govern activities in Europe but also affect activity in the digital markets of the United States. Even if the U.S. continues to avoid establishing oversight of digital markets, the interconnected nature of the internet will assure European decisions will have American effects.

American consumers might see the effects of the DMA in the policies attendant to mobile device app stores. These DMA-driven changes include allowing for alternative payment systems, as well as new policies pertaining to the sideloading of software and the ability to remove previously unremovable default apps. Arguably, the recent ability on the Apple App Store to access previously inaccessible video game software that emulators classic video games is attributable to the DMA.

Such beneficial consequences for American consumers, however, should not stand in the way of establishing an American approach to digital oversight that is compatible with the new approach. Thus far, by avoiding the heavy lifting of domestic digital policy, U.S. lawmakers have left those decisions to be made by the platforms themselves acting as pseudo-governments. The EU has reclaimed the digital sovereignty of its citizens through a revolutionary new regulatory model. The Rubicon has been crossed whether American policymakers choose to assert similar leadership.

Revolutions do not retreat. The die is cast.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft are general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the authors and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- The analogy is drawn not in praise of the resulting Caesarian dictatorship, but as an example of bold initiatives with consequential and lasting results.

- Over the last 40 years in the United States, the antitrust focus on concentration and broad competitive effects has been superseded by the “consumer welfare standard” that focused more on the effect of an activity on prices. Recent lawsuits have been attempting to return to focusing on competitive effects.

Commentary

Crossing the regulatory Rubicon: The future of digital regulation is being defined in Europe

June 7, 2024