The once-a-century public health crisis we have just gone through also created a once-a-century crisis for public education. The average American student lost the equivalent of a half a year of learning, with larger losses still for the most disadvantaged students. Just a modest share of that learning loss has been remediated. Why haven’t we made more progress overcoming pandemic learning loss? What lessons does this suggest for how to make more progress moving forward?

The federal government did a number of things right. It gave schools funding. The U.S. Secretary of Education encouraged districts to spend that on one of the few educational interventions shown to be capable of accelerating learning by enough to overcome pandemic learning loss: high-dosage tutoring (HDT). And when it became clear districts were slow to mount remediation efforts in the chaotic aftermath of the pandemic, districts got an extension for using their federal dollars.

The challenge in hindsight is that some of the program design principles most important for making HDT helpful to students turn out to be quite counterintuitive. Those lessons come from observations of how tutoring has played out around the country by the Annenberg Center at Brown and our own University of Chicago and MDRC-based team. These aren’t the only challenges to implementing tutoring, of course, but making these counterintuitive changes can go a long way towards realizing the potential of high-dosage tutoring to overcome pandemic learning loss–and perhaps even make progress on the large disparities in student learning that pre-dated the pandemic as well.

1. Don’t over-pay tutors

Over-paying tutors means serving fewer students, or serving the same number of students worse.

Classroom teaching is an enormously difficult job that requires years of pedagogical training to learn how to handle classroom management and dealing with the variability in student academic backgrounds within the class. The average teacher salary of $57,000 (nearly equal to median total household income in the U.S.) reflects the need to pay competitive wages to hire highly skilled and experienced people. Many people argue teachers should be paid even more. So it makes sense that many public schools would conclude that the same level of experience and skill–and hence salary–is needed for the instructors in their tutoring programs. Many school districts made this choice before the pandemic with tutoring supported by Supplemental Education Services of Title 1, and many districts also made the same choice as they stood up new tutoring programs with federal pandemic relief funds.

But tutoring, by shrinking class sizes from upwards of 30 students per instructor down to as low as two or three students per instructor, qualitatively changes the teaching task, and so qualitatively changes the type of prior training and experience needed to be successful. In our own team’s work with the non-profit Saga Education, we have found that people without the training and experience necessary to be a classroom teacher (yet), and who command a much lower salary–in our studies, less than half of what the average teacher is paid–can be effective tutors right out of the gate. (In Saga’s case, the tutors are commonly hired right out of college and are willing to do a public service for a year, or they are middle-aged career-switchers or even college work-study students.)

Schools are used to thinking that the higher skilled, higher-paid the instructor, the better. That rule of thumb might be a useful starting point in the context of regular classroom teaching, where teachers are tasked with being pedagogical experts and classroom management experts, not to mention all the other tasks big and small like engaging parents and families, administering assessments, compliance to school and district policies, and even planning field trips. But that calculus is radically different for tutoring, a much easier instructional task by comparison. Of course tutoring salaries need to be high enough to recruit the necessary number of tutors–but no higher. High salaries are the enemy of scale, and also the enemy of the sort of high dosage (measured in weekly contact hours) that the research suggests is a key to tutoring’s effectiveness.

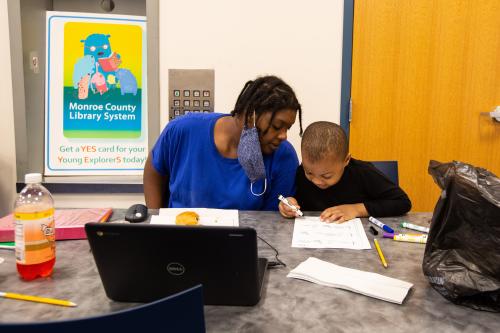

2. Don’t try to fit tutoring in by adding instructional time

Students lost a massive amount of instructional time during the pandemic. It’s intuitive to think that the solution will be to figure out how to add instructional time beyond the normal school day to overcome that. We’ve seen many districts around the country try to deliver tutoring through, for example, after-school programming, or trying to get students to do virtual tutoring at home in the evenings or on weekends. The logic behind trying this is easy to see. Unfortunately, we have not seen any successful examples ourselves of getting this approach to work–or specifically, getting students to consistently participate–at large scale.

The surest way to get students to consistently participate at large scale in the sort of high-dosage tutoring they need to catch back up to grade level is to carve out time during the school day itself.

Some school administrators worry about where the time will come from. Won’t taking some time away from extended reading or math instructional blocks for reading or math tutoring (the subjects that are the most common focus of tutoring) be self-defeating by robbing Peter to pay Paul? No. Tutoring is so much more effective than the model of one teacher trying to teach thirty children simultaneously, that student learning greatly accelerates even if the tutoring time requires cutting into regular reading or math time. Or, if part of the tutoring time comes from electives or specials, won’t that reduce student enthusiasm for school? Based on our work in Chicago, we think the answer is no. It’s true electives and specials can make students more engaged with school. But there’s something else that can do that, too–being able to follow what the teacher is teaching in reading and math class. We see this in our Chicago study: Carving out time for tutoring during the school day did not diminish student engagement with school. There are burgeoning examples in the field about how school leaders are finding time during the school day. Put differently: this is a solvable problem.

3. The computer screen is not the enemy

Thanks to the pandemic, “Zoom” has become a four-letter word to a large segment of parents, teachers, and children in America. The last thing many schools want at this point is to put children in front of a computer screen again.

The reluctance to give students more screen time is very understandable, but a missed opportunity. Parents, teachers, and children are all correct that the 30th hour in a week spent on a computer yields low returns. The best available data show that there are diminishing marginal returns to student time spent on a high-quality computer assisted learning (CAL) platform. But what that observation misses is that the first few hours seem to yield very high returns.

Our research with CPS and Saga Education show that strategic, limited use of computer time as part of tutoring programs (not more than half the total time spent in the program) can greatly reduce the number of tutors that need to be hired, and thus greatly reduce costs, without having to compromise student learning at all.

Counterintuitive approaches to high-dosage tutoring can help students rebound.

The good news is that we’ve learned a lot about what works to alleviate the COVID-19 educational crisis, but we cannot wait any longer to scale this promising solution nationwide. The challenge is that change will require change–schools need to do some things that are counterintuitive through the lens of ‘normal’ classroom instruction but vitally necessary if we are to scale the benefits of high-dosage tutoring.

We have no time to waste.

Commentary

Counterintuitive strategies for overcoming pandemic learning loss with high-dosage tutoring

June 3, 2024