If public-health authorities’ worst predictions come true, COVID-19 may never disappear. That means the world will have to live with the virus and develop effective treatments and measures to contain the virus.

Mobile contact-tracing technology has emerged as one such measure to track population movements and alert individuals when they come into contact with an infected person. But such technology faces enormous obstacles. These tools become more effective as a greater percentage of smartphone users download and use them: 60% of the population is often cited as an optimal metric, but the apps can also work at lower rates. With the novel coronavirus continuing to spread in the United States and major American universities and technology companies actively developing digital contact-tracing tools, understanding whether the American people would be willing to use such technology to stem the outbreak has never been more important.

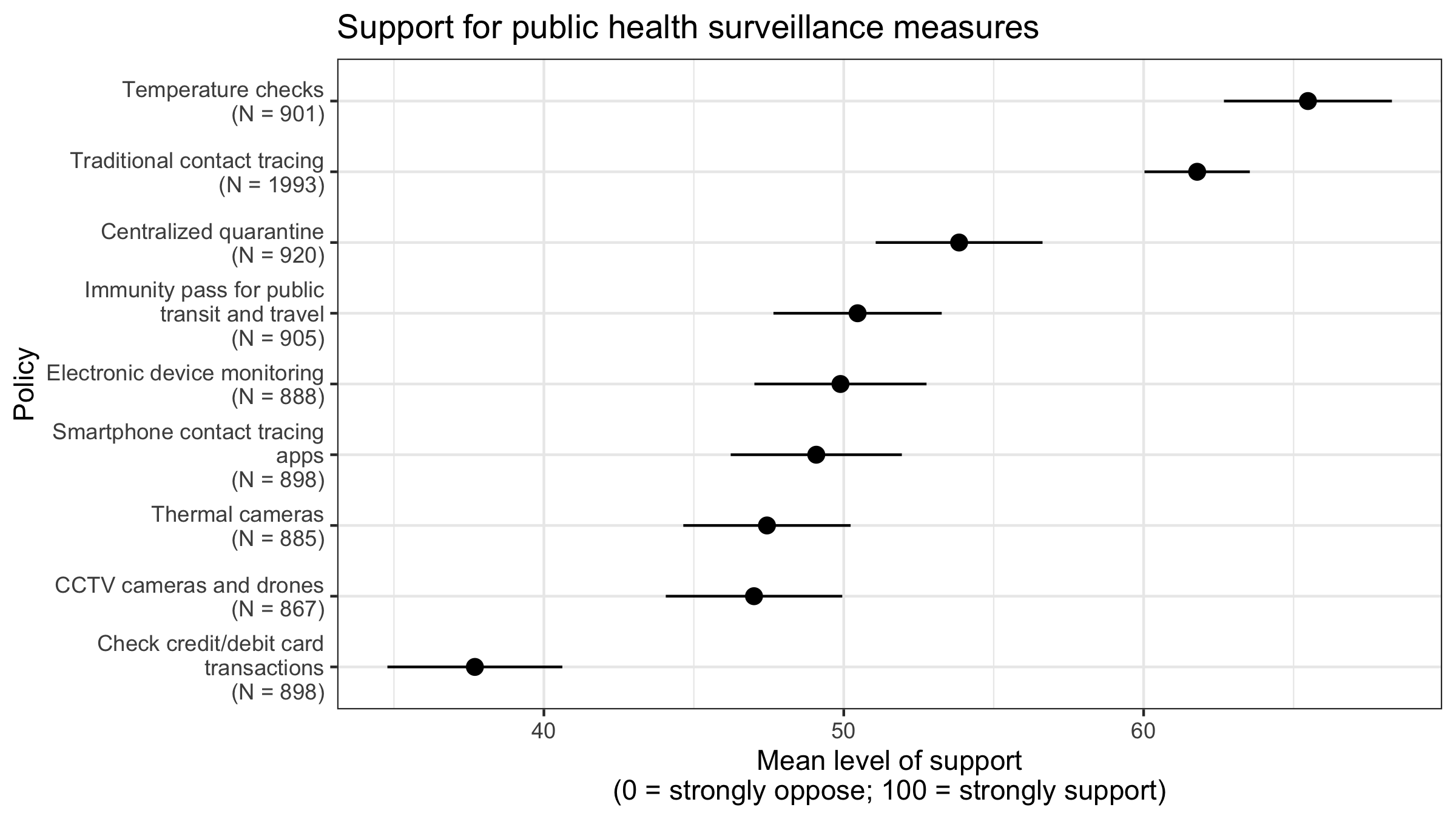

But Americans continue to be deeply skeptical of such technology. In a nationally representative study of 2,000 Americans between June 24 and June 25, 2020, we found that 42 percent of Americans indicated they would download and use a mobile contact-tracing app, raising questions about whether such technology will be adopted widely enough to be effective. In a bit of good news for developers, support among Americans for digital contact tracing tends to increase with stronger privacy protections.

In countries where digital contact-tracing efforts are already underway, widespread adoption continues to be a major problem. In Singapore, where authorities in March rolled out one of the first contact-tracing apps, up-take has only reached 20 percent. Iceland announced recently that 38 percent of its population had downloaded its version, the highest level of voluntary adoption of an automated contact tracing app to date.

Black Americans, a group already disproportionately affected by the virus, expressed greater skepticism about traditional contact tracing compared with white Americans, but the differences are not so stark when it comes to contact-tracing apps. Forty-five percent of Black Americans support the government expanding traditional contact tracing compared to 61 percent of white Americans. When told about a hypothetical contact-tracing app, only 36 percent of Black smartphone users indicated that they would be likely to download the app, compared with 44 percent of white Americans. In light of these concerns, widespread testing, traditional contact tracing, and targeted outreach to marginalized communities will continue to be important. But there is reason to believe that support for digital contact tracing will improve, especially as the disease continues to spread. Those surveyed were more likely to opt in if they knew someone who had tested positive for COVID-19. As the number of cases continue to increase in the United States, so too will the number of people supportive of these tools.

Our survey indicates significant levels of distrust toward the technology companies and public health authorities administering contact-tracing technology, but when we described the way that some companies are trying to build contact-tracing tools with privacy and security in mind, we find significantly higher levels of support for apps. While some European countries and Singapore are using a centralized model for storing COVID-related health data generated by apps, others, such as the Apple-Google API, deploy a decentralized system of storage. The latter system also relies on Bluetooth signal exchanges that do not reveal the identity or location of the users, helping safeguard against the potential misuse of data. Among our respondents, only 44 percent expressed willingness to download a hypothetical app with centralized data storage, while 49 percent were willing when the app was described as using decentralized storage.

The technology nonetheless elicits visceral reactions about whether it can adequately preserve privacy. When asked about a hypothetical contact-tracing app, nearly half of respondents think the app would violate privacy and make tech companies too powerful. In open-ended answers, respondents frequently cited concerns about overreach by the government or tech companies. Open-ended comments include “[I]t’s a continuation of the ‘big brother’ approach,” “I think this is an extreme form of controlling our daily lives,” and “It violates my rights and I will leave my phone at home.”

This skepticism isn’t surprising—just consider the position of the Cambridge Analytica scandal or the Snowden revelations in the public imagination—but the public-health community need not pay the price for governments’ and tech firms’ prior sins. App developers should recognize the importance of the privacy-preserving measures and follow through on decentralized data storage while dropping considerations of GPS location tracking. Our analysis points to the need for public education campaigns that clarify what the tools are and, especially, what they are not doing.

Furthermore, state governments might consider passing legislation, as Australia has done, that would impose fines for data misuse. If legislation is not feasible, state public health authorities and tech companies should establish a multi-stakeholder board to oversee the technology. That board should include not only public health experts but also advocates for groups that are disproportionately harmed by COVID-19 or could be disproportionately harmed by the introduction of digital contact tracing.

Contact-tracing apps are not meant to replace other public health measures, nor should they. Indeed, beyond the concern about effectiveness and security of these apps, public health officials should realize that digital contact tracing introduces new challenges of access and equity. The technology on which it relies—cell phones—is not spread evenly across societies but fragmented. The tool will not help populations who have lower levels of smartphone ownership such as the elderly or homeless, who are also particularly vulnerable to the virus.

Research is required to determine whether the apps are effective and whether they generate significant amounts of false positives or negatives, so that the technology can improve. Its roll-out should of course be as accurate as possible, but our research shows that public confidence and in turn efficacy will grow if, or as, it proves its worth.

Sarah Kreps is a professor of government and Milstein Faculty Fellow in Technology and Humanity at Cornell University.

Baobao Zhang is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Nina McMurry is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sept. 11, 2020: This article has been updated to include new survey results that were collected after a software glitch was discovered that may have impacted the survey results from Android users.

Apple and Google provide financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Contact-tracing apps face serious adoption obstacles

May 20, 2020