Chapter

06

CLIMATE CHANGE:

Adapting to a new normal

Essay 1

Essay 2

Turning political ambitions into concrete climate financing actions for Africa

One of the main targets of the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) in Sharm El-Sheik, Egypt, was “to accelerate global climate action through emissions reduction, scaled-up adaptation efforts and enhanced flows of appropriate finance.” While the breakthrough agreement on a new “Loss and Damage” Fund for vulnerable countries is a welcome development, progress on climate finance leaves much to be desired. This is worrisome for African countries.

Recent reports on climate change such as the African Economic Outlook 2022 and the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have reiterated that the climate crisis is likely to worsen, especially in Africa, and that the time for action to avert the impending catastrophe is now. World leaders have missed (again) the opportunity to move from mere political commitments and ambitions to concrete actions.

Africa’s climate paradox

As the late Kofi Annan perfectly put it, all continents are in the same boat when it comes to addressing climate change. However, individual regions and countries are not equally responsible for global environmental problems. This principle of common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities is at the core of climate justice and just energy transition.

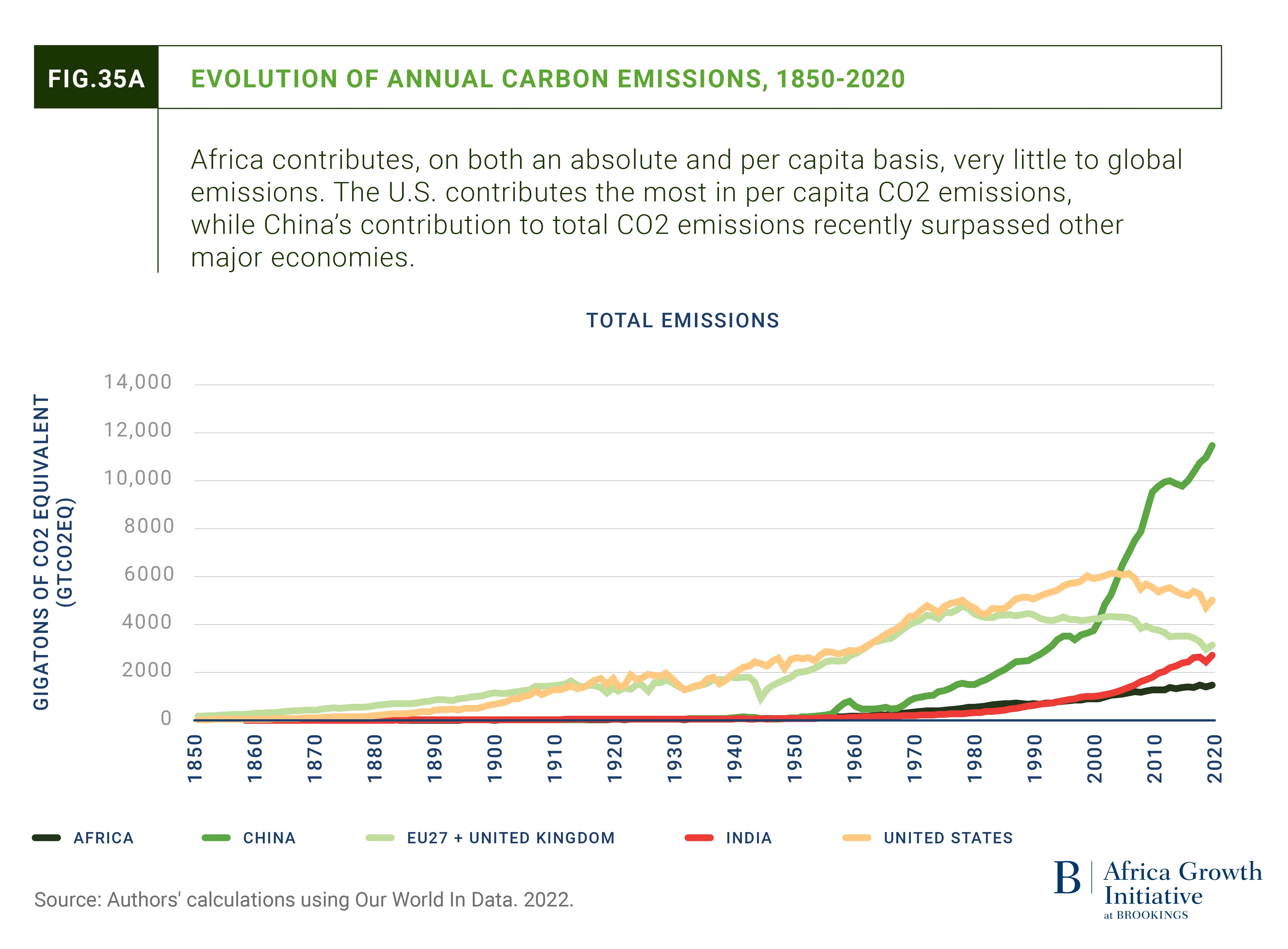

Africa’s case is especially concerning. The continent is the least polluting region1 of the world but faces a disproportionate burden from the impact of climate change. Between 1850 and 2020, Africa’s contribution to global emissions remained below 3 percent2 and yet, it lost about 5 percent to 15 percent annually of GDP per capita growth between 1986 and 2015. About 70 percent of the used global carbon budget is accounted for by just the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and China (Figure 35a). An average African had a carbon footprint of just 0.95 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2eq) in 2020, well below the 2.0 tCO2eq required to achieve the net-zero transition target. On the other extreme, an average American had a carbon footprint of up to 14 tCO2eq, fifteen times higher than that of an average African (Figure 35b).

From climate finance commitments to reality and at scale

The $100-billion promise,3 made by developed countries since 2009 at COP15 in Copenhagen, has still not been achieved. According to the OECD,[OECD.2022. “Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2016-2020.”] climate financing provided and mobilized by developed countries reached $83.3 billion in 2020, some $16.7 billion below the target. Indeed, a 2020 report commissioned by the United Nations concluded the only realistic scenario is that the $100-billion target will be out of reach in the short- to medium-term.

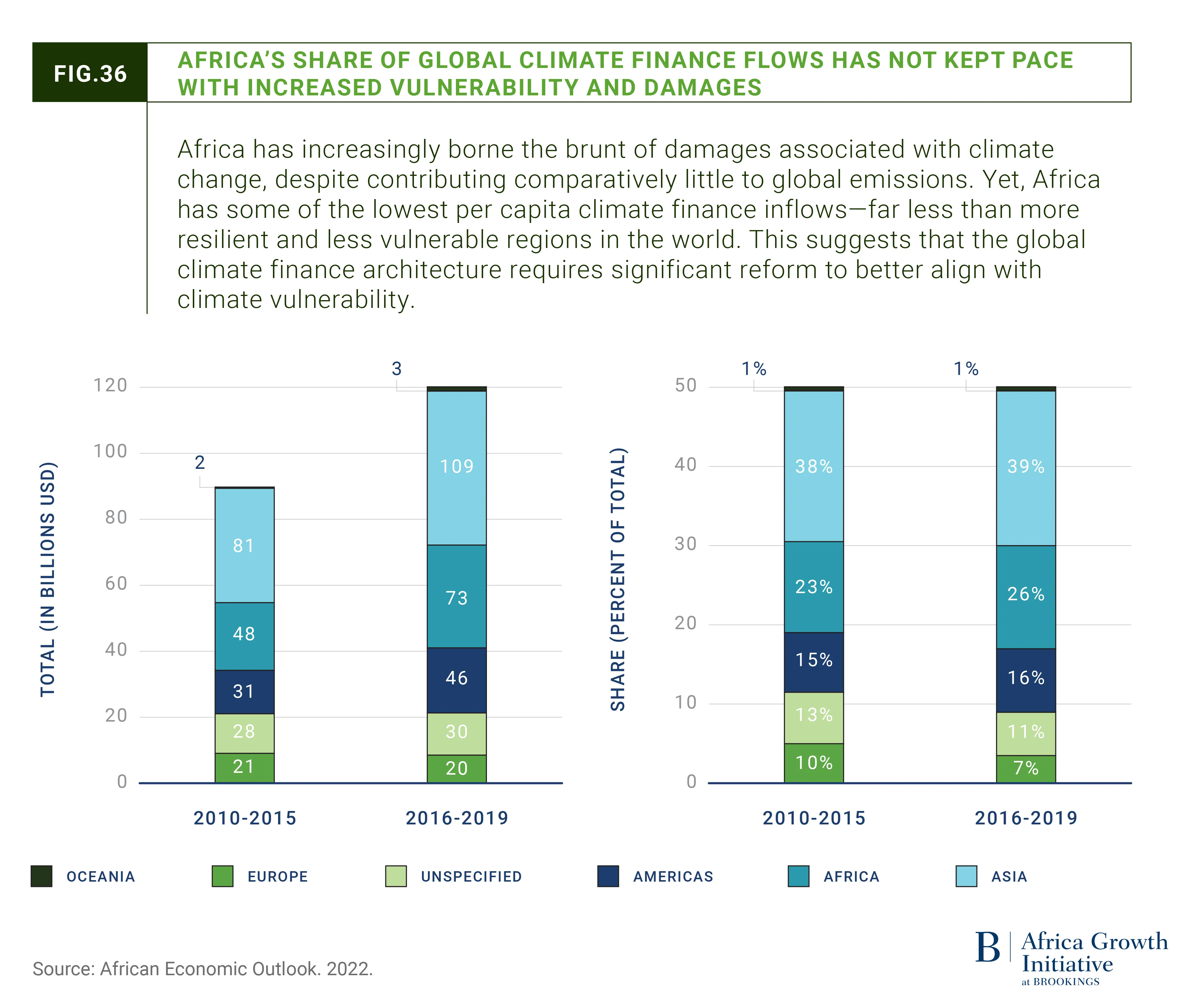

Africa’s share of global climate finance—provided and mobilized by developed countries for developing countries—increased by only 3 percentage points on average during 2010 to 2019, from 23 percent ($48 billion) in 2010–2015 to 26 percent ($73 billion) in 2016–2019 (Figure 36). This means that Africa benefited from $18.3 billion a year from 2016–2019, far behind Asia, which benefited $27.3 billion a year, over the same period. Yet, Africa accounted for about 40 percent of all countries eligible to benefit from this support, compared with only 20 percent for Asia. In addition, between 2010 and 2019, debt instruments (mostly loans) accounted for about two-thirds of all climate finance channeled to Africa, out of which two-fifths were on non-concessional terms.

Climate finance inflows to Africa are dwarfed by the enormity of resources needed for Nationally Developed Contributions (NDCs), estimated to range from about $1.3 trillion to $1.6 trillion between 2020 and 2030, or $118.2 billion to $145.5 billion per year over this period. Under the current climate finance trends, Africa’s annual financing gap could thus reach an estimated average of $108 billion per year until 2030. This climate injustice needs urgent attention.

Mobilizing more climate finance for Africa is within the reach of the global community. For instance, between January 2020 and September 2021, the global community mobilized about $17 trillion through various fiscal measures in response to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost $15.3 trillion (or 90 percent of these fiscal measures) was mobilized by G-20 economies. This demonstration of political will and innovative use of fiscal policy rules to address the global threat posed by COVID-19 is commendable. Like COVID-19, climate change is a global commons problem but perhaps with even longer-term and systemic impacts.

Why Africa deserves more in climate financing

Mobilizing climate finance to avert the growing climate catastrophes in developing countries calls for similar political will and collective action. To this end, an important milestone is for the international community and developed countries to step up to the plate in mobilizing and providing the requisite climate resources to developing countries.

“Ultimately, climate change is a global commons problem. Climate solutions will not be sustainable unless all actors play their part. The climate challenge cannot be addressed if any country fails to meet its Nationally Determined Contributions.”

Achieving this will require significant reform of the current global climate finance architecture,4 to ensure that the most vulnerable countries (especially in Africa), effectively harness climate resilience opportunities. The structure, flow, and scale of the global climate finance architecture, as currently designed, is misaligned with climate vulnerability. For example, as illustrated in Figure 36 above, more resilient and less vulnerable regions receive more climate finance, in per capita terms, than their less resilient but more vulnerable counterparts. Moreover, the climate finance architecture is modelled to mirror the current global financial architecture that is risk averse and discriminatory against fragile economies. The loose definition of climate finance has also led to proliferation of various climate finance instruments, including debt instruments. The latter exacerbates debt vulnerabilities in countries where climate impacts are already constraining fiscal health.

There is thus need for a clearer definition of climate finance, better coordination among existing global climate finance facilities, dedicated climate initiatives, as well as enhanced harmonization of funding requirements that can channel climate finance flows to the most climate-vulnerable countries. While African countries do have their part to play, the principle of common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities requires that the most polluting countries bear the greatest burden of climate financing.

Ultimately, climate change is a global commons problem. Climate solutions will not be sustainable unless all actors play their part. The climate challenge cannot be addressed if any country fails to meet its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

And the world cannot expect Africa to implement its NDCs if the expected climate finance flows to fund the conditional NDCs, are not made available. Should the current trends continue, it is certain that Africa will not achieve its NDCs by 2030. By implication, the global community will not be able to reach the Paris Climate Accord.

The charge due to custodians of the world’s lungs

It is time to rebalance the scales in Africa’s favor when it comes to climate finance. The African continent is home to 16 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of the world’s remaining rainforests5—yet Africa attracts only 3.19 percent of global climate finance ($30 billion of $940 billion global climate flows), and the pledges to accelerate adaptation and mitigation financing of $100 billion by 2020 in developing countries are yet to fully materialize.6 Climate finance can be a catalytic tool for fiscal stability, especially for African countries that are struggling with economic recovery, amid multiple global shocks.

However, for African countries and non-state actors to attract increased climate finance and play a greater role in structuring the green financial architecture, Africa must position itself as a worthy investment destination for climate finance focused on long-term development issues. To achieve this, I propose a few key areas of focus for policymakers. First, countries must have green investment plans, and second, it is critical to bring the private sector to the table and to give it space to innovate. In addition, policymakers should use public finance to de-risk private investment and have a regulatory environment that enables doing business with variable financing tools. Lastly, developed countries must deliver on the pledges already made without any further and new conditionalities to spur green development for a common 1.5 degrees future.

“Of the great rainforests in the world, only the Congo rainforest has enough standing forest left to absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases.”

African Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), that is countries’ action plans to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts, should be accompanied by national investment strategies that prioritize green infrastructure and natural resource protection. These can create a green development pathway that promises economic growth opportunities, industrialization, and jobs, propelling Africa past a more traditional, less green infrastructure and development approach.

Country platforms should also encompass the private sector, so that there is a cohesive approach as to who will invest where, and who is best placed to tackle the varying aspects of mitigation and adaptation and protection. A good example of this approach on leveraging the private sector is the proposal by members of the “Nairobi Declaration on Sustainable Insurance” that identified the African insurance sector as a key climate mitigation and adaptation agent; and re-affirmed its triple role of risk manager, risk carrier, and investor through commitment to a Africa climate risk management fund. This fund will cover $14 billion worth of climate and nature-related risks such as floods, droughts, and tropical cyclones through innovative insurance products and solutions. These kind of innovations by the private sector are in line with what the Paris Agreement envisioned.

Second, debt-for-climate swaps and carbon markets should be rolled out more broadly as part of the solution to debt crises which plague a long and growing list of African nations. This effort starts with valuing Africa’s wealth in the totality of its nature assets. Nature has become the world’s most important commodity, and its protection is paramount for the world’s survival. According to the World Resources Institute, of the great rainforests in the world, only the Congo rainforest has enough standing forest left to absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases.7

Commercializing such nature assets, and making sure they attract fair value and benefit neighboring communities, is a key feature of the Africa Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI)8—an initiative that has created a roadmap for developing African voluntary carbon markets, with the aim to accelerate and scale carbon credit production on the continent. The initiative proposes to leverage an advanced market commitment (AMC), which in essence is an upfront guarantee from buyers and multiple corporations, to purchase African carbon credits. This AMC will help send a strong demand signal and incentivize appetite for good quality and innovative credits. There is huge potential in making carbon markets work to attract more climate finance.

Third, there is need for gender-informed investing to enhance climate adaptation and resilience. At its core, this means acknowledging climate action as a development issue; recognizing that the climate crisis is not “gender-neutral,” and that women and girls are disproportionately affected; and finally, that the devastating impacts of extreme climate occurrences cause more economic scarring to the poorest and most vulnerable in our societies. 2xCollaborative has developed a gender-lens investing toolkit that can, and should be, widely used to promote gender-lens climate finance to businesses and adaptation projects, involved or led by women.

We cannot afford the current architecture of global green finance to perpetuate existing disparities in those it serves. It is time for African countries to unite, strategically position themselves, and demand that the world does more to deliver climate finance for the continent; it promises great return for all, and it is what is due to the custodians of the “lungs of the world.”

Endnotes

- 1. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2021. “Climate Change 2021: The Physi-cal Science Basis.” Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- 2. AfDB.2022. “African Economic Outlook 2022”. African Development Bank.

- 3. Jocelyn Timperley. 2021. “The broken $100-billion promise of climate finance — and how to fix it.”

- 4. Charlene Watson, Liane Schalatek, and Aurélien Evéquoz. 2022. “The Global Climate Finance Architecture.”

- 5. World Bank Africa Region. 2017. “Forests in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges & Opportunities.” The Program on Forests (PROFOR).

- 6. Naran, Baysa. 2022. “Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data: 2011-2020.” Cli¬mate Policy Initiative.

- 7. Harris, Nancy and David Gibbs. 2021. “Forests Absorb Twice as Much Carbon as They Emit Each Year.” World Resources Institute.

- 8. ACMI is a joint initiative of GEAPP, SE4All, UNECA and supported by the UN Climate Change High Level Champions.

Viewpoints

Managing the compounding debt and climate crises

Gracelin Baskaran explains how climate vulnerability is deepening debt challenges in sub-Saharan Africa and how policymakers can manage it.

Global decarbonization: Industrial opportunities for Africas

Yacob Mulugetta considers how African countries can insert themselves into green manufacturing value chains.

Africa’s Blue Economy can continue to deliver huge benefits to the continent

U. Rashid Sumaila urges investment in a sustainable and inclusive African blue economy.

Climate adaptation finance in Africa

Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez and Jamal Saghir discuss sustainable climate adaptation investment strategies for Africa.

The case for climate financing

Mahmoud Mohieldin makes the case for increasing climate finance flows to Africa.

Gold mining, climate change, and Africa’s transition

John Mulligan explains how the gold industry can help confront the challenges and opportunities of a changing climate in Africa.

Next Chapter

07 | Africa's Cities Realizing the new urban agenda