The following testimony was submitted to the Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Spending Oversight on March 20, 2024 for the “Strengthening international cooperation to stop the flow of fentanyl into the United States” hearing.

Dear Chair Hassan, Ranking Member Romney, and distinguished members of the Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Spending Oversight Subcommittee of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs:

Thank you for holding this hearing entitled, “Strengthening International Cooperation to Stop the Flow of Fentanyl into the United States.” This is a crucial issue that deserves the attention of the subcommittee and its members. I am honored to have this opportunity to submit this testimony as a statement for the record.

I am a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution where I direct the Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors and the Brookings series the Fentanyl Epidemic in North America and the Global Reach of Synthetic Opioids and codirect the Africa Security Initiative. Illicit economies, such as the drug trade and wildlife trafficking, organized crime, corruption, and their impacts on U.S. and local security issues around the world are the domain of my work and the subject of several of the books I have written. I have conducted fieldwork on these issues in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. In addition to studying China’s and Mexico’s role in various illegal economies over the past two decades, I have been directing over the past three years a new Brookings workstream on China’s role in illegal economies and Chinese criminal groups around the world.

The Brookings Institution is a U.S. nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The testimony that I am submitting represents solely my personal views, and does not reflect the views of Brookings, its other scholars, employees, officers, and/or trustees.

Executive summary

U.S. domestic prevention, evidence-based treatment, harm reduction, and law enforcement measures are fundamental and indispensable for countering the devastating fentanyl crisis.

However, given the synthetic opioid epidemic’s extent and lethality in North America and its likely eventual spread to other parts of the world, even supply control measures with partial and limited effectiveness can save lives and thus need to be designed smartly and robustly.

China and Mexico are key actors whose collaboration is necessary for controlling supply. Yet unfortunately the United States has found establishing counternarcotics cooperation with both countries deeply challenging.

Between August 2022 and November 2023, China ended cooperation altogether because Beijing instrumentalizes international law enforcement assistance and subordinates it to its geostrategic relationships. A recent U.S. diplomatic breakthrough with China provides an important promise of strengthened cooperation, the robustness of which is to be seen.

Mexico eviscerated cooperation to a bare minimum because President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration has been unwilling and uninterested in mounting any serious law enforcement policy toward Mexican criminal groups.

Mexico continues to calculate that it can get away with only sporadic, minimal, and inadequate counternarcotics collaboration as long as it leverages its ability to hamper or permit the flow of undocumented migrants to the U.S.-Mexico border and as long as the United States depends on it for migration control. If the United States conducted a comprehensive immigration reform that provided legal work opportunities to those currently seeking protection and opportunities in the United States through unauthorized migration, it would have far better leverage for inducing meaningful and robust counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation from Mexico.

Until 2019, China was the principal source of finished fentanyl for the U.S. illegal market. Since China scheduled the entire class of fentanyl-type drugs in May 2019, it is the principal source of precursor chemicals for fentanyl. And since many precursors are dual use, they have not been placed on control schedules. Chinese brokers knowingly sell these chemicals to Mexican criminal groups for the production of fentanyl.

From the precursors, the Sinaloa Cartel and Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) synthesize fentanyl in Mexico and then smuggle it to the United States.

China

After more than two years of China purposefully denying counternarcotics cooperation to the United States and failing to mount adequate internal enforcement against precursor flows, Beijing agreed to restart cooperation in November 2023.

China’s principal motivation was to stabilize the U.S.-China relationship.

But adroit and appropriately tough U.S. diplomacy and actions also played an important role in bringing China back to cooperation. The United States was able to raise China’s reputational costs by organizing the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats and placing China on its annual list of major drug-producing or transit countries. The U.S. Department of Justice issued a set of innovative and powerful indictments against Chinese networks selling nonscheduled precursors to Mexican cartels, and the Department of Treasury sanctioned various Chinese firms for their complicity. The denial of visas to various Chinese officials and business executives also proved an effective tool.

Nonetheless, China still subordinates its anti-drug and anti-crime cooperation to its strategic calculus and views counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation as a strategic tool to leverage for its other objectives. Thus, even while China’s current goal is to reduce tensions, China’s drug cooperation is vulnerable to new crises in the bilateral relationship. Moreover, Beijing rarely acts against the top echelons of large and powerful Chinese criminal syndicates that provide the Chinese government with various services unless they specifically contradict a narrow set of interests of the Chinese government.

To demonstrate its commitment, China took several steps in the run-up to and after the November summit between President Xi Jinping and President Joe Biden, such as sending out notices to Chinese pharmaceutical companies that it was stepping up monitoring and shutting down websites selling precursors to Mexican criminal actors.

At the first meeting of the resurrected U.S.-China counternarcotics working group, China agreed to further cooperation steps, including those it previously denied to the United States, such as joint anti-money laundering efforts (AML) and cracking down on pill press exports.

Strengthening AML cooperation is all the more important since Chinese money launderers have become some of the world’s leading ones and the to-go-launders for Mexican criminal groups. They utilize a wide range of innovative methods that avoid international wire transfers and pose particular obstacles for law enforcement.

Worrisomely, Mexican cartels are increasingly sourcing an expanding array of protected and unprotected species in Mexico coveted in China to pay for fentanyl and methamphetamine precursor chemicals. Because of the potency-per-weight ratio of synthetic opioids, precursor chemicals for fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are uniquely suited to be paid for by wildlife products. This method of payment generates dangerous threats to public health and biodiversity since it can spread zoonotic diseases.

Key indicators of China’s seriousness about counternarcotics collaboration include:

- China’s responsiveness to U.S. intelligence provision.

- Reciprocal sharing of intelligence.

- Arrests and prosecutions in China.

- The extent and consistency of China’s monitoring and regulating of Chinese pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

- Its willingness to adopt Know-Your-Customer (KYC) laws.

Yet China already warns that it is unlikely to deliver cooperation on several of these elements. Beijing is still insisting, for example, that it cannot prosecute nonscheduled substances, claiming the lack of material support laws pertaining to organized crime. Because of economic costs, China also remains unmotivated to mandate and promote KYC laws.

Mexico

U.S.-Mexico counternarcotics cooperation has become deeply inadequate during the López Obrador administration in Mexico. From the start of his administration, López Obrador sought to withdraw from the Merida Initiative that underpinned U.S.-Mexico anti-crime collaboration since 2009. A series of crises in the bilateral relationship have hollowed out cooperation. The U.S.-Mexico Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities that replaced the Merida Initiative in the fall of 2021 reiterated many aspects of counternarcotics cooperation on paper, but on the ground joint counternarcotics cooperation remains weak and insufficient.

Mexico has played an active role in the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats, co-chairing its public health working group. Yet López Obrador’s false claims that no fentanyl is consumed in Mexico and his opposition to the provision of the overdose medication naloxone undermines the credibility and effectiveness of Mexico’s leadership in that area.

In the spring of 2023, López Obrador also began falsely denying that fentanyl is produced in Mexico.

Aware of the U.S. focus on migration, the Mexican government takes the minimum action necessary to placate the United States regarding fentanyl.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) operations in Mexico remain hampered, though Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) has received more cooperation from the Mexican government.

Acting on U.S. intelligence, the Mexican government engages in occasional collaboration in high-value targeting of key drug cartel leaders. In 2023, the Mexican government arrested and extradited one of the leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel, Ovidio Guzmán López, and later arrested another key Sinaloa operative.

However, the sporadic targeting of an odd member of criminal groups’ top echelons, if not accompanied by a systematic effort to disrupt the groups’ middle operational layer and the entire scope of their operations, is insufficient. At the national level, the Mexican government rarely interferes with criminal groups’ operations in any systematic way.

At the United States’ insistence, and as a result of brave journalistic investigative work, the Mexican government did shut down some of the dangerous and criminal-group-linked pharmacies selling fentanyl- and methamphetamine-laced drugs and other dangerous and prescription substances, such as antibiotics, without prescription. These pharmacies are highly dangerous vectors of spreading substance-use disorder and potentially overdose death. Shutting down these pharmacies is imperative. But effective prosecution of their operators is essential, otherwise the networks will simply open up new pharmacies selling dangerous drugs.

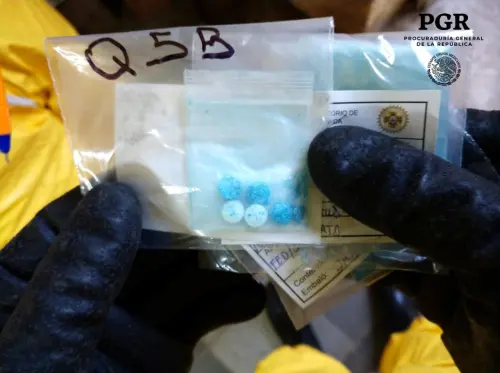

Similarly, lab busting alone, while necessary, is inadequate since fentanyl and methamphetamine labs are easy to rebuild. Yet the Mexican government often does not appear to follow lab busts with investigations, arrests, and prosecutions. Worse, crucial investigations by Reuters have repeatedly revealed that the Mexican government systematically and grossly exaggerates the number of busted labs.

Brave journalistic and research work has been crucial to motivate the Mexican government’s enforcement actions. Yet Mexico is one of the world’s most dangerous places for journalists in the world. López Obrador has frequently lashed out against the media and engaged in a systematic effort to weaken Mexico’s checks and balances and institutions of transparency and accountability. In a recent and particularly troubling case, López Obrador exposed the photo, phone number, and personal information of the New York Times bureau chief in Mexico who subsequently suffered serious threats. The U.S. Congress and executive branch must strongly condemn such actions by the Mexican government, demand they will not be repeated, and take actions to ensure this.

Beyond journalists, honest Mexican officials who want to collaborate with the United States and brave civil society members, environmental activists, and business community leaders who stand up to the criminal groups at severe risk to their lives and the lives of their families often find no protection from the Mexican government.

López Obrador’s strategy of “hugs, not bullets” toward criminal groups never

articulated any security or law enforcement component. Over time, it became obvious that López Obrador simply does not want to confront the criminal groups with force. López Obrador abolished the Federal Police, yet the National Guard he created in its stead does not have any investigative capacities or mandates. It can merely, and often ineffectively, patrol the streets.

Yet violence in Mexico remains high and brazen and is spreading geographically and into wider aspects of people’s lives. Some of these battles now approximate insurgent battlefields and tactics. Less visible forms of violence—disappearances and intimidation of civil society activists, business community members, and government officials—have escalated across the country. Mexico’s current election season is on track to be the most violent ever, with criminal groups seeking to influence elections at all levels through bribery and intimidation.

Essentially, the Mexican president has hoped that if he does not interfere with Mexico’s criminal groups, they will eventually redivide Mexico’s economies and territories among themselves, and violence will subside. That policy has been disastrous for many reasons: Most importantly, because it further saps the already-weak rule of law in Mexico, increases impunity, and subjects Mexicans, their institutions, and the legal economies to the Mexican criminal groups’ tyranny.

Having expanded far beyond illegal commodities, Mexican criminal groups are also increasingly taking over legal economies, such as fishing, mining, logging, agriculture, alcohol production and retail, and public services such as water distribution in various parts of Mexico. The takeover goes far beyond extortion and often seeks to control the entire vertical chain of production. This takeover of legal economies does not only augment the cartels’ money laundering tools and increase their revenues, it is also a means of political control.

Mexican criminal groups’ increasing territorial and economic power, brazen violence, takeover of legal economies in Mexico, and the impunity they enjoy in Mexico raise significant questions about near-shoring to Mexico as a derisking strategy for China. What kind of supply-chain, legal, and other liabilities and risks are there for U.S. companies operating in Mexico or with Mexican counterparts amid a collapsing rule of law?

Mexican criminal groups increasingly interact with Chinese criminal groups and fishing fleets. The high presence of Russian spies in Mexico also raises the possibility of their increased relations with Mexican criminal groups.

Overall, Mexican criminal groups govern an expanding scope of territories, economies, and institutions and people in Mexico. These profoundly pernicious developments have taken place even as Mexico’s economy and public policy, not just public safety, have become increasingly militarized.

Policy recommendations

Since Mexican drug cartels have diversified their activities into a wide array of illicit and licit commodities, primarily focusing on drug seizures close to the source is no longer sufficient for effectively disrupting fentanyl smuggling and criminal networks implicated in it.

Rather, it is imperative to counter all of the Mexican criminal groups’ economic activities and their connections to Chinese criminal actors and political patrons around the world. This includes countering poaching and wildlife trafficking from Mexico and illegal logging and mining in places where the Mexican cartels have reach, acting against illegal fishing off Mexico and around Latin America and elsewhere, and shutting down wildlife trafficking networks into China. These are all increasingly important elements of countering Mexican and Chinese drug-trafficking groups and reducing the flow of fentanyl to the United States.

Reinforcing U.S.-China cooperation

To motivate China’s responsiveness to U.S. intelligence provision and reciprocal sharing, the U.S. Congress could request regular, if closed-door, reports on these aspects of cooperation.

The U.S. government should also consider the number of arrests and prosecutions in China and the consistency and extent of China’s monitoring of its chemical and pharmaceutical companies, and the removal of websites selling synthetic drugs to criminal actors as important bases for China’s removal from the Majors List.

The United States should continue to strongly encourage China to adopt and enforce KYC laws and punish violators, being ready to raise the costs of China’s KYC non-compliance by denying Chinese suppliers and industries market access. The United States should continue encouraging China and its chemical and pharmaceutical industries to adopt the full array of global control standards.

The United States should reinforce China’s willingness to engage bilaterally and multilaterally in AML cooperation against Chinese criminal networks.

The United States should continue developing packages of leverage on Chinese actors and when appropriate continue with its effective policy of denying U.S. visas.

In anticipation of backsliding in China’s cooperation, the United States should strengthen multilateral efforts within the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats. Specifically, it should concentrate on mobilizing a subgroup of countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific region and include methamphetamine in the portfolio of actions. These countries carry important weight with China on law enforcement efforts.

Inducing cooperation from Mexico

In its law enforcement engagement with the Mexican government, the United States should prioritize:

- Continuously shutting down Mexican pharmacies that sell fentanyl- and methamphetamine-adulterated drugs and prosecuting the networks that operate them.

- Dismantling drug trafficking networks, particularly their middle-operational layers, not merely interdiction raids on labs and drug seizures.

- Supporting strengthened Mexican prosecutorial actions against criminal actors.

The United States should also continue to seek the restoration of joint U.S.-Mexico law enforcement operations inside Mexico and of Mexico’s willingness to systematically share samples of seized drugs with U.S. law enforcement agencies.

The U.S. Congress and executive branch must strongly condemn actions by the Mexican government that threaten the freedom of the press and jeopardize the safety of journalists, especially when they are U.S. citizens. The U.S. government should ensure that such actions by the Mexican government will not be repeated.

The United States has various tools to induce better cooperation from Mexico:

Designating Mexican cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) would enable intelligence gathering and strike options for the United States military, such as against some fentanyl labs in Mexico. But the number of available strike targets in Mexico would be limited, and the strikes would not robustly disrupt the criminal groups. Neither would the FTO designation add authorities to the economic sanctions and anti-money laundering and financial intelligence tools that the already-in-place designation of Transnational Criminal Organization carries. Moreover, such unilateral U.S. military actions in Mexico would severely jeopardize relations with our vital trading partner and neighbor; the FTO designation could significantly limit and outright hamper other U.S. foreign policy options, measures, and interests.

The United States should be ready to resort to significantly intensified and intrusive border inspections, even if they significantly slow down the legal trade and cause substantial damage to Mexican goods, such as agricultural products.

The United States should develop packages of leverage, including indictment portfolios and visa denials, against Mexican national security and law enforcement officials and politicians who sabotage rule of law cooperation in Mexico, facilitate cartel activities, and undermine law enforcement cooperation with the United States.

Expanding and smartening U.S. measures against criminal actors

The United States also has crucial opportunities to strengthen its own law enforcement actions against dangerous drug supply by reconceptualizing the counternarcotics effort more broadly as against all activities of criminal actors smuggling dangerous contraband. This would include:

- Truly adopting a whole-of-government approach to countering fentanyl-smuggling entities.

- Authorizing a wide range of U.S. government agencies, including the Departments of State and Defense, to support U.S. law enforcement against Mexican and Chinese criminal actors, fentanyl trafficking, and crimes against nature.

- Collecting relevant intelligence on crimes against nature to uncover criminal linkages to foreign governments and criminal groups and elevate such intelligence collection in the U.S. National Intelligence Priorities Framework.

- Expanding the number and frequency of participation of U.S. wildlife investigators and special agents in Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF).

- Increasing the number of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agents and investigators, which have flatlined since the 1970s even as the value of wildlife trafficking has significantly increased.

- Designating wildlife trafficking as a predicate offense for wiretap authorization.

Basic overview and core issues

Synthetic opioids are the source of the deadliest and unabating U.S. drug epidemic ever. Since 1999, drug overdoses have killed over 1 million Americans,1 a lethality rate that has increased significantly since 2012 when synthetic opioids from China began supplying the U.S. demand for illicit opioids. In 2021, the number of fatalities was 106,699;2 in 2022, it is estimated to have been 107,477.3 Most of the deaths were due to fentanyl, consumed on its own or mixed into fake prescription pills, heroin, and increasingly, methamphetamine and cocaine.

The structural characteristics of synthetic drugs, such as fentanyl, including the ease of developing similar, but not scheduled, synthetic drugs and their new precursors—increasingly a wide array of dual-use chemicals—pose immense structural obstacles to controlling their supply.

U.S. domestic prevention, evidence-based treatment, harm reduction, and law enforcement measures are fundamental and indispensable to countering the devastating fentanyl crisis.

However, given the synthetic opioid epidemic’s extent and lethality in North America and its likely eventual spread to other parts of the world, even supply control measures with partial and limited effectiveness can save lives and thus need to be designed as smartly and robustly as possible.

China and Mexico are key actors whose collaboration is necessary for controlling supply. Yet, unfortunately, the United States has found establishing counternarcotics cooperation with both countries deeply challenging. In fact, in recent years, cooperation with both countries has been deeply inadequate as both China and Mexico hollowed out antidrug collaboration with the United States.

China ended cooperation altogether because it instrumentalizes international law enforcement assistance and subordinates it to its geostrategic relationships. A recent U.S. diplomatic breakthrough with China provides an important promise of strengthened cooperation, the robustness of which is to be seen in 2024 and beyond.

Mexico eviscerated cooperation to a bare minimum because President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration has been unwilling and uninterested in mounting any serious law enforcement policy toward Mexican criminal groups and has stayed away from substantially confronting them.

Mexico continues to calculate that it can get away with only sporadic, minimal, and inadequate counternarcotics collaboration, and unresponsiveness to key U.S. interests as long as it leverages its ability to hamper or permit the flow of undocumented migrants to the U.S.-Mexico border and as long as it provides other migration services to the United States, such as hosting migrants awaiting U.S. asylum hearings.

Until 2019, China was the principal source of finished fentanyl for the U.S. illegal market. Unscrupulous Chinese brokers, acting in violation of U.S. laws, shipped fentanyl to dealers in the United States, often through postal and other courier services. In May 2019, after years of intense U.S. diplomacy, China placed the entire fentanyl class of synthetic opioids on a regulatory schedule.4 China had to pass new laws to be able to do so.5 China also adopted stricter mail monitoring procedures. As a result, instead of shipping finished fentanyl to the United States, Chinese brokers switched to shipping precursor chemicals to criminal groups in Mexico for the synthesis of fentanyl there. Some of these precursor chemicals have been scheduled, but others remain unscheduled, in part because they have widespread use in the legal manufacturing of chemical products and pharmaceutical goods.

Nonetheless, even when Chinese brokers sell nonscheduled chemicals to Mexican criminal groups, they often supply these precursors and pre-precursors with the explicit knowledge that the drugs will be synthesized into fentanyl and distributed in the illegal market. Chinese sellers sometimes accompany the chemicals with recipes of how to synthesize illegal drugs like fentanyl from the precursors they provide. They purposefully cater to drug trafficking groups in their directed Spanish advertisements that often bundle together uncontrolled fentanyl precursors, common cocaine adulterants, and unscheduled methamphetamine precursors. Some of their ads even highlight their capacities to “clear customs in Mexico.”6 In other cases, Chinese companies operating online without Chinese internet signatures advertise their connections to international drug traffickers, such as in India, to appeal to illegal buyers in Mexico.7

U.S.-China counternarcotics cooperation

After more than two years of China purposefully denying counternarcotics cooperation to the United States and failing to mount adequate internal enforcement, Beijing agreed to restart cooperation in November 2023. Its principal motivation was to stabilize the U.S.-China relationship, but U.S. diplomacy and actions also played an important role in bringing China back to cooperation.

The diplomatic breakthrough was announced at the November 2023 meeting between President Joe Biden and President Xi Jinping.8 As part of the renewed cooperation, a joint U.S.-China counternarcotics working group was recreated.

To demonstrate its seriousness, China’s National Narcotics Control Commission sent out notices to Chinese pharmaceutical companies across the country’s provinces that it was now monitoring and enforcing precursor export controls.9 Like in 2019 and 2020, China also took down some Chinese websites that were selling precursor chemicals to international criminal groups.

In return, Washington removed sanctions from the Institute of Forensic Science in China, which the United States had designated because of the institute’s complicity in human rights abuses in Xinjiang.10 China has long sought the removal of those sanctions.

In January 2024, the resurrected U.S.-China counternarcotics commission held its first meeting. High-level Chinese officials promised ambitious outcomes, even as non-action hedging did not completely disappear.11

U.S. officials have told me that China has started acting on U.S.-provided intelligence about Chinese drug networks. Compared to the many years when the commission’s previous iterations essentially amounted to platforms for mutual recrimination, at least some temporary progress appears to have been made.

China also agreed to expand its multilateral engagement on synthetic drug control, such as once again reporting drug data to the United Nations anti-drug agencies.

For the first time, China was willing to include several measures on which it had previously resisted cooperation. In one, China committed itself to enforcement cooperation on pill press exports, a vital element of the illegal drug trade enabling the production of lethal, fake pills. China had long shunned regulatory controls on pill presses to maximize its economic interests.

China also committed itself to AML cooperation, another element on which China had long denied collaboration with the United States. Previously, U.S. officials were frustrated by the lack of China’s cooperation with U.S. investigations into the role of Chinese networks laundering money for Mexican cartels. Overall, U.S. law enforcement agencies have had little visibility into China’s banking sector and China’s application of its AML controls. This time, representatives from Chinese banks, including the Bank of China, attended some of the U.S.-China counternarcotics side meetings in Beijing in January 2024.

Strengthening AML cooperation is always very useful, since beyond disrupting financial flows to criminal actors, AML investigations generate powerful intelligence on criminal networks. In the case of fentanyl and China, such collaboration is all the more important since Chinese money launderers have become some of the world’s leading ones. Their collaboration with Mexican cartels is so efficient that they have been displacing the Black Peso Market.12 Chinese money laundering networks are also facilitating organized criminal groups’ financial transactions in Europe.13

Chinese money laundering networks utilize a wide variety of money laundering tools and constantly innovate their methods. Crucially, they often manage to bypass the U.S. and Mexican formal banking systems, thus evading established anti-money laundering measures. They simplify one of the biggest challenges for the cartels: moving large amounts of bulk money subject to law enforcement detection.

Chinese money laundering methods frequently avoid international wire transfers. Instead, they interface with the formal banking systems only within a country—China, Mexico, or the United States, and sometimes only within China. As described in Drazen Jorgic’s Reuters special report,14 through a system of mirror transactions across several countries, Chinese money launderers deposit equivalent amounts of money across the money laundering chain. They interact with criminal actors, such as Mexican cartels, through encrypted platforms, burner phones, and codes. U.S. investigations and court cases reveal that the Bank of China has been among the Chinese financial firms utilized by Chinese operators to launder money for Mexican cartels.15

Laundering through casinos is analogous to these informal money transfers: Bulk cash is brought to a casino in Vancouver, for example, where the cartel-linked individual loses it while his money laundering associate in Macau wins and pays the Chinese precursor smuggling networks.16 In recent years, such as between 2021 and 2023, China clamped down on money laundering and gambling in Macau and encouraged countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, such as Australia, to cooperate with its effort to repatriate money to China.17

Other money laundering and value transfers between Mexican and Chinese criminal networks include trade-based laundering, a form of money laundering extremely challenging for law enforcement to counter. An example of trade-based laundering includes Chinese launderers for CJNG buying shoes in China and reselling them in Mexico to give the cartel the necessary cash.18

In the United States, Chinese money launderers have recently begun using counterfeit Chinese passports to open burner bank accounts. They swap cash for cashier’s checks, with which they purchase iPhones and other luxury goods sought in China. The resale of these goods in China generates further profits for the money laundering networks.19

Just like in Australia, a primary location of Chinese money laundering, Chinese money laundering networks in the United States are also moving into real estate, in addition to utilizing cryptocurrencies.20

Other pernicious forms of money laundering and value transfer utilize Mexican wildlife and plant products, such as marine and terrestrial animals and timber. Beyond facilitating crime, they pose massive threats to Mexican biodiversity and risk spreading catastrophic zoonotic epidemics and pandemics, including to the United States.

Mexican cartels are increasingly sourcing an expanding array of protected and unprotected species in Mexico coveted in China—for Traditional Chinese Medicine, aphrodisiacs, other forms of consumption, or as a tool of speculation—to pay for fentanyl and methamphetamine precursor chemicals. Such products include turtles, tortoises, crocodilians and other reptiles, jellyfish, abalone, sea cucumber, and other seafood, parrots, and jaguars as well as various hardwoods.21 The swim bladder of the endemic and protected Mexican totoaba fish, which is highly prized in Chinese markets, is a notorious example.22 Instead of paying in cash, Mexican cartels pay Chinese precursor brokers in these commodities.

The amount of value generated by such wildlife commodity payments, likely in the tens of millions of dollars, may not cover all of the precursor payment totals and is unlikely to displace other methods of money laundering and value transfer. But the potency-per-weight ratio of synthetic opioids makes their precursors very cheap—their total value likely also amounts to only tens of millions of dollars.23 Thus, precursor chemicals for fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are uniquely suited to be paid by wildlife products, and this method of payment generates highly dangerous threats to public health and biodiversity.

Moving bulk cash across the U.S.-Mexico border is an increasingly dated method.24

Why China restarted counternarcotics cooperation

Two factors brought about China’s collaboration turnaround:

- Chinese geostrategic calculations.

- Adroit and appropriately tough U.S. diplomacy.

In the last several years, U.S.-China relations deteriorated to a level of tensions unseen in decades across a wide range of issues—including military alliances and power projection in the Asia-Pacific, China’s facilitation of Russia’s egregious war against Ukraine, Chinese spying of sensitive technologies, and Taiwan.25 With China’s economic growth slowed since COVID-19, the intensified competition has put further strains on China.26 Both countries came to desire a more stable rivalry and looked for a way to put a floor underneath their relationship’s freefall. Resurrecting bilateral counternarcotics enforcement and military-to-military exchanges and increasing cooperation on climate change mitigation and artificial intelligence were all opportunities to do so.27

Moreover, U.S. diplomacy effectively raised the reputational and other costs for China and Chinese actors. In July 2023, the United States organized and launched a new Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats.28 Although China prides itself on being a tough drug cop and tends to be very active in global counternarcotics diplomacy, it abstained from joining while nearly 100 countries signed up.29

China’s counternarcotics reputation took another hit in September 2023 when the United States placed Beijing on its annual list of major drug-producing or transit countries (aka the Majors List).30 While some countries have become indifferent to the listing, calculating they can escape sanctions through U.S. national security interest exceptions, these reputational costs do matter to China.

Crucially, in 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a set of innovative and powerful indictments against Chinese networks selling nonscheduled precursors to Mexican cartels, and the Department of Treasury sanctioned various Chinese firms.31 The indictments centered on prohibitions of material support to organized crime groups and revealed Chinese suppliers are knowingly selling to Mexican cartels and providing them with formulas and kits on how best to process the nonscheduled chemicals into fentanyl.32 China has long excused its inaction against these flows by insisting it cannot act against nonscheduled chemicals, such as the dual-use precursors from which much of fentanyl is produced today.

As an important pressure tool, the United States denied visas to various Chinese officials and business executives, while the U.S. Congress held multiple hearings on China’s role in the U.S. drug epidemic and a U.S. Senate delegation to China emphasized the issue.33

Monitoring U.S.-China collaboration

It is unlikely that China will end its approach of subordinating its anti-drug and anti-crime cooperation to its strategic calculus. The United States has long hoped to get China to delink anti-crime cooperation from the overall state of the bilateral relationship and establish strong law enforcement cooperation separate from geopolitics.

In fact, China sees counternarcotics and more broadly international law enforcement cooperation as strategic tools that it can leverage to achieve other objectives. As Beijing’s hopes for improvements in U.S.-China relations declined in 2021, so too did China’s willingness to coordinate with Washington on counternarcotics objectives. Thus, even though China’s current goal is to reduce tensions, China’s drug cooperation is vulnerable to new crises in the bilateral relationship.

Moreover, Beijing rarely acts against the top echelons of large and powerful Chinese criminal syndicates unless they specifically contradict a narrow set of Chinese government interests. Chinese criminal groups cultivate political capital with Chinese authorities and government officials abroad by also promoting China’s political, strategic, and economic interests.

Key indicators of China’s seriousness about counternarcotics collaboration include:

- China’s responsiveness to U.S. intelligence provision.

- Reciprocal sharing of intelligence.

- Arrests and prosecutions in China.

- The extent and consistency of China’s monitoring and regulating of Chinese pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

- China’s willingness to adopt KYC laws.

Yet China already warns that it is unlikely to deliver cooperation on several of these elements.

For example, China cautions that it will not be able to mount many arrests and prosecutions.

Furthermore, China still insists that it cannot prosecute nonscheduled substances, claiming the lack of material support laws pertaining to organized crime.34 If these laws are genuinely lacking in China, the world’s most extensive police and surveillance state, it should either strengthen the laws or find other mechanisms in its draconian drug laws, such as conspiracy and fraud charges, to prosecute Chinese violators.35

Beyond regular, not just one-off, messaging that China is now serious about controlling drug exports and the above-cited prosecutions, China’s willingness to promote the adoption of KYC laws and practices across these industries is an important measure and goal. Designed to protect institutions against fraud, participation in organized crime, corruption, money laundering, and terrorist financing by mandating that companies and individuals perform due diligence on their customers and do not engage in business with those that fall into the above categories, KYC laws are now commonplace around the world. Yet China has been reluctant to adopt such policies, calculating that such measures are too economically costly.36

Conversely, the United States should not judge the extent of China’s cooperation by the number of drug-induced deaths in the United States. Even if China were to robustly cooperate, deaths may not dip: In illicit drug markets, there are always lags of months or years between effective supply actions and retail changes. Besides, Mexican cartels have stockpiles of precursors, and they can source them from other sources, such as India or South Africa.37

Moreover, if drugs like xylazine (which is not responsive to the overdose medication naloxone) and other synthetic opioids like nitazenes start spreading beyond the East Coast (and escalate in Europe), overdose deaths will spike beyond the currently high levels.38

U.S.-Mexico counternarcotics cooperation

U.S.-Mexico counternarcotics cooperation also remains challenging, and over the past five years has become deeply inadequate. Anti-drug collaboration has weakened even though Mexico is an important neighbor and economic partner of the United States and Mexican and U.S. societies are interconnected through familial ties. The Mexican government has hollowed out the cooperation even though Mexican cartels are key vectors of fentanyl production and trafficking and of violence in Mexico and Latin America. At the core of the problem lies the disinterest of the López Obrador administration in confronting Mexican criminals with effective law enforcement. U.S. preoccupation with migration flows and U.S. reliance on the Mexican government to stop these flows give the Mexican government leverage to deflect U.S. demands for stronger law enforcement actions against fentanyl and against the cartels.

From the start of his administration, López Obrador sought to withdraw from the Merida Initiative—the U.S.-Mexico security collaboration framework signed during the Felipe Calderón administration. Instead, he sought to redefine the collaboration extremely narrowly: U.S. assistance to Mexico was intended to reduce demand for drugs in Mexico, while the United States focused on stopping the flow of drug proceeds and weapons to Mexico and reducing drug demand at home. Previous Mexican governments also sought to direct U.S. law enforcement’s focus to those two types of illicit flows but were also willing to collaborate inside Mexico. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trilateral Fentanyl Committee has elevated countering firearms trafficking.39

After the United States arrested former Mexican Secretary of Defense Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos in October 2020 for conspiring with a vicious Mexican drug cartel, López Obrador threatened to end all cooperation and expel all U.S. law enforcement personnel from Mexico.40 To avoid that outcome, the Trump administration handed Cienfuegos over to Mexico where he was rapidly acquitted.

But despite this significant U.S. concession, Mexico’s counternarcotics cooperation remained limited. Meanwhile, U.S. law enforcement activities in Mexico were shackled and undermined by a December 2021 Mexican national security law on foreign agents.41 As stated by Matthew Donahue, a former high-level Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) official, since then and because of the continually immense level of corruption and cartel infiltration in Mexican security agencies, Mexican law enforcement spends more time surveilling DEA agents than it does cartel members.42

With the threat of Mexico’s unilateral withdrawal from the Merida Initiative escalating, the United States government worked hard to negotiate a new security framework with Mexico—the U.S.-Mexico Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities43—in the fall of 2021. The United States emphasized the public health and anti-money laundering elements of the agreement, as the Mexican government had sought. The framework reiterates multiple dimensions of counternarcotics cooperation, including law enforcement.

After the United States launched the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats, Mexico expressed a welcome interest in promoting public health tools for dealing with drug use. It has been cochairing the coalition’s working group on health issues. Yet the Mexican government’s authority is undermined by López Obrador’s false claims that no fentanyl is used in Mexico, even as fentanyl use is spreading beyond Mexico’s northern states.44 The López Obrador administration has even actively hampered the accessibility of the overdose medication naloxone in Mexico, suggesting a total ban on its use even as the medication is crucial for saving and managing opioid use disorder.45 Not even law enforcement officers sent to bust drug labs in Mexico, where they could be exposed to lethal doses of fentanyl, are provided with naloxone. These actions by the López Obrador administration jeopardize the lives of Mexican people and the country’s public health and weaken its credibility in international fora on public health approaches to drugs.

Moreover, López Obrador began falsely denying that fentanyl is produced in Mexico, and deceptive statements were made at his behest by other high-level Mexican officials and agencies.46 Presently, the Mexican president insists that fentanyl is only pressed into fake pills in Mexico, which he does not appear to believe is of sufficient concern. Blaming fentanyl use in the United States on U.S. moral and social decay, including American families not hugging their children enough (the statement an apparent nod to his strategy of confronting Mexican criminals with “hugs and not bullets”), the Mexican president has also denied that fentanyl is increasingly consumed in Mexico.47 With such statements, López Obrador is not just unwittingly (or knowingly) echoing China’s rhetoric, but also publicly dismissing two decades of a policy of shared responsibility for drug production, trafficking, and consumption between United States and Mexico.

Thus, even after the announcement of the Bicentennial Framework, U.S.-Mexico law enforcement cooperation has been limping at best. Aware of the U.S. focus on migration, the Mexican government takes the minimum actions necessary to placate the United States regarding fentanyl. It concentrates its interdiction efforts at the border with the United States, and especially on migration, but tends to take few actions against the cartels away from the border.

DEA operations in Mexico remain hampered and limited by the Mexican government, undermining law enforcement’s capacity to incapacitate and deter Mexican criminal groups. Other U.S. law enforcement actors, such as HIS, have been able to build back some cooperation with Mexican law enforcement actors. Some Mexican government agencies are even sharing some intelligence with the United States.

Acting on U.S. intelligence, the Mexican government engages in occasional collaboration in high-value targeting of key drug cartel leaders. In January 2023, acting on U.S. intelligence, Mexican authorities arrested one of the leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel, Ovidio Guzmán López. In September 2023, they extradited him to the United States. Given his crucial role in directing the Sinaloa Cartel’s fentanyl operation, his capture and arrest were significant developments. Extradition is important: In the United States, top cartel operatives and their political and government sponsors cannot count on escaping from prison and a high rate of prosecution failure. And extradition and subsequent interrogations in the United States allow for the development of better tactical and strategic intelligence by law enforcement. In November, the Mexican government arrested Néstor Isidro Pérez Salas (“El Nini”), the notorious head of security for the Chapitos wing of the Sinaloa Cartel.

Demonstrating resolve and priority-targeting focus on criminal groups is important. Appropriately, the Biden administration has elevated fentanyl and synthetic opioids to a top-level threat. However, the sporadic targeting of the odd member of the criminal groups’ top echelons, if not accompanied by a systematic effort to disrupt the groups’ middle operational layer and the entire scope of their operations, is insufficient. At the national level, the Mexican government rarely interferes with criminal groups’ operations in any systematic way.

At the United States’ insistence, and as a result of brave journalistic investigative work, the Mexican government did shut down some of the dangerous and criminal-group-linked pharmacies selling fentanyl- and methamphetamine-laced drugs and other dangerous controlled or prescription substances without prescription, such as antibiotics. These pharmacies sprung up in Mexico’s international tourist areas since the COVID-19 outbreak. They are highly dangerous vectors of spreading substance-use disorder and potentially overdose death.

Proliferating in places such as the Mayan Riviera and Los Cabos over the past three years, these pharmacies are physical buildings that appear like other Mexican pharmacies. Yet they openly advertise drugs such as antibiotics, anabolic steroids, and prescription opiates and sell them illegally without a prescription. Investigative work by The Los Angeles Times and separately by Vice discovered that drugs sold as Percocet, for example, also contained fentanyl and methamphetamine.48 Other drugs sold without prescription, such as oxycodone, Xanax, and Adderall, were often fentanyl-laced fakes. During my June 2023 fieldwork in Mexico, shop assistants in these pharmacies claimed they could mail any of these drugs to the United States without a prescription.

Amid an already terrible drug epidemic, these pharmacies greatly magnify the threats to public health. U.S. citizens have long been accustomed to buying medications that are too expensive in the United States from Mexico. Unwittingly, intending to buy other medication, they may end up buying drugs causing lethal overdose or addiction. The legitimate veneer of these pharmacies also exposes a much wider set of potential customers to fentanyl and other dangerous drugs, ranging from teenagers to the elderly. Because the pharmacies aggressively target international tourists in major vacation resort areas, they also export the fentanyl epidemic to other regions of the world, such as Western Europe. Many of these pharmacies are likely linked to the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG. Further funding the Mexican cartels and other drug trafficking networks, the geographic spread of fentanyl use would augment the global public health disaster.

The adulteration of fake medications with fentanyl and methamphetamine is not the sole problem. The unauthorized sale of antibiotics without prescription at these pharmacies also poses other massive global public health, economic, and security harms, such as the intensified emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

Shutting down these unscrupulous pharmacies to minimize the criminals’ market access and to reduce exposure to customers is imperative. Simply seizing illicit pills while letting the pharmacies operate is inadequate. Shutdowns and strong prosecutorial actions are necessary against suppliers.

Yet while these pharmacies operate in violation of Mexican laws, in plain sight, and visibly saturate major tourist areas, it took a long time for Mexican regulatory authorities, such as Mexico’s Federal Commission for Protection Against Sanitary Risks (COFEPRIS), to mount action. In June 2023, COFEPRIS finally raided three such pharmacies in Los Cabos, arresting four operators and seizing some 25,000 pills.49 In August, Mexican officials seized illegal drugs from and shut down 23 pharmacies on the Mayan Riveria.50 And in December, Mexican authorities raided and shut down 31 pharmacies in Ensenada, Baja California.51

These are important actions to disrupt overdose deaths and addiction. They cannot remain one-off operations and need to be consistently mounted by the Mexican government. It is also crucial not simply to shut the pharmacies down but to mount investigations into their criminal sponsors and arrest and dismantle the networks behind them. Effective prosecution of their operators is essential. If the networks are left standing, they will simply open up new pharmacies selling dangerous drugs.

Similarly, lab busting alone is inadequate. Fentanyl and meth labs are easy to rebuild. While they cannot be left operating outside of sting operations and controlled delivery investigations, it is essential to use lab raids to gather intelligence for criminal network mapping and subsequent arrests, prosecutions, and network dismantling. Such investigations and prosecutions have rarely been mounted in Mexico during the López Obrador administration.

Worse, crucial investigations by Reuters have repeatedly revealed that the Mexican government systematically manipulates data regarding drug lab busts and grossly exaggerates the numbers of labs taken down.52

The identification of various Mexican pharmacies’ criminal operations, the exposure of the Mexican government’s data manipulation to exaggerate its interdiction efforts, and a myriad of other key revelations about the scope of criminal groups’ takeover in Mexico and their infiltration into Mexican institutions and politics have come as a result of courageous investigative work by Mexican and international journalists and researchers who often face substantial risks to their lives and the lives of their families. Mexico is one of the highest-risk countries for journalists, with many journalists killed and few perpetrators held accountable.53 One study by the free speech group “Article 19” found that in 2022, a Mexican journalist was attacked every 13 hours.54 The attacks’ frequency appears to have risen as Mexico enters its elections season. Even journalists placed under the Mexican government’s official protection continue to suffer attacks.55 Yet throughout his presidency, López Obrador has attacked media outlets and journalists for doing their crucial work.

In a recent and particularly troubling demonstration of his effort to suppress the freedom of media, López Obrador exposed the photo, phone number, and personal information of the New York Times bureau chief in Mexico, who subsequently suffered serious threats.56 The U.S. Congress and executive branch must strongly condemn such actions by the Mexican government, demand they will not be repeated, and take actions to ensure this.

Some collaboration has persisted at the sub-federal level in Mexico also. Yet just like with journalists, all too frequently, the Mexican government does not provide support to honest and committed Mexican law enforcement and justice officials who want to collaborate with the United States and act against Mexican criminal groups’ increasing ambition to dominate ever larger aspects of Mexican life, politics, and economics. Such honest Mexican officials as well as brave civil society members, environmental activists, and business community leaders who stand up to the criminal groups against all odds and at severe risk to their lives and the lives of their families often find no protection from the Mexican government.

The lack of support for and outright undermining of well-motivated and committed Mexican government officials,57 the lack of protection for those who stand up to criminal groups, and attacks on media are part and parcel of López Obrador’s systematic effort to weaken checks and balances in Mexico and the country’s institutions and systems of transparency and accountability.

The growing power of Mexican criminal groups amid inadequate law enforcement

The substantial weakening of Mexico’s willingness to meaningfully collaborate with the United States’ anti-drug and anti-crime efforts is not simply a matter of López Obrador’s dislike of the intensity of cooperation achieved during the Calderón administration. It also crucially reflects his unwillingness to strongly confront criminal networks in Mexico.

At the beginning of his administration, López Obrador announced a strategy of “hugs, not bullets” toward criminal groups. The strategy sought to emphasize socio-economic programs to deal with crime and address the causes that propel young people to join criminal groups. Poorly designed and pervaded by corruption even in the socio-economic aspects, the strategy never articulated any security or law enforcement policy toward criminal groups. Over time, it became obvious that López Obrador simply did not want to confront the criminal groups with any kind of force.

At the beginning of his administration, López Obrador abolished the Federal Police—because of its infiltration by Mexican criminal groups, a systematic and pervasive problem for all of Mexico’s law enforcement forces for decades. (Since the 1980s, the many iterations of law enforcement reforms have failed to expunge such infiltration and corruption across Mexican agencies.) Early efforts to reform Mexico’s municipal police forces, highly vulnerable to criminal intimidation and infiltration and frequently lacking capacities, rapidly withered.

López Obrador instead created the National Guard, staffed mostly by Mexican soldiers and police officers from the former Federal Police and now under the command of the Mexican military. However, the National Guard is not and could never be an adequate replacement for the Federal Police. The Federal Police, with all its faults, had the greatest investigative capacities and mandates, while the National Guard has no investigative mandates and very little capacity. It can only act against crime in flagrancia or as a deterrent force by patrolling the streets, a highly ineffective strategy.

To the extent that the Mexican military or National Guard are deployed to a particularly violent area of Mexico, they mostly only patrol narrow zones, sometimes even without responding to crime battles raging nearby. Some of these battles now approximate insurgent battlefields as cartels such as CJNG increasingly deploy weaponized drones and land mines to depopulate areas and keep law enforcement forces away.58

Visible violence, such as gun battles and sieges of government offices, have spread to other parts of Mexico, dramatically escalating in places like Guerrero and Chiapas.59 Hidden, but no less dangerous, violence—in the form of disappearances and intimidation of civil society activists, business community members, and government officials—has escalated across the country.60

The current election campaign is on track to become Mexico’s most violent ever.61 Criminal groups no longer simply seek to corrupt and intimidate candidates once they are elected. Through coercion, including assassinations, and corruption, they increasingly seek to determine who can run in the first place. They deploy bribery, intimidation, and violence to shape elections at all levels of the Mexican government.

Yet they can get away with that violence. Since 2017 more than 30,000 Mexicans have been killed per year, including in 2023, while more than 112,000 remain disappeared.62 The effective prosecution rate for homicides in Mexico continues to hover at an abysmally low 2 percent and remains in single digits for other serious crimes.63

Investigative authorities in Mexico are predominantly under the Office of the Attorney General (Fiscalía General de la República, FGR), the Federal Ministerial Police, and state prosecutorial offices. But as with other law enforcement institutions in Mexico, the FGR’s capacities are limited, overwhelmed by the level of crime in Mexico, and suffer from criminal infiltration, corruption, and political interference despite decades-long efforts at reform.

Essentially, the Mexican president has hoped that if he does not interfere with Mexico’s criminal groups, they will eventually redivide Mexico’s economies and territories among themselves, and violence will subside. That policy has been disastrous for many reasons: Most importantly, it further saps the already-weak rule of law in Mexico, increases impunity, and subjects Mexican people, institutions, and legal economies to Mexican criminal groups’ tyranny. But it is also problematic because Mexico’s out-of-control criminal market, plagued by a bipolar and increasingly internationalized war between the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG, has little chance to effectuate such stabilization.

Yet this do-little policy has augmented the impunity that criminal groups enjoy in Mexico and motivated them to resort to more and more brazen violence and acquire progressively greater power. Within Mexico, Mexican criminal groups often control extensive territories where the government has only limited influence and sporadic access and some of which have become outright no-go zones for government officials. In other areas, they dictate governance terms to government officials.

Having expanded far beyond illegal commodities, Mexican criminal groups are also increasingly taking over legal economies and public services such as water distribution in various parts of Mexico. The cartels are pressuring, penetrating, and taking over mining, logging, fisheries, mezcal and tequila production, alcohol and cigarette distribution and other retail, and agriculture—and not just avocados.

This takeover of legal economies does not only augment the cartels’ money laundering tools and increase their revenues. It is also a means of political control.

Such legal economy takeovers go far beyond extortion—which is enormously widespread as many businesses in Mexico do not have the capacity to shield themselves from extortion by Mexican criminal groups. Mexican criminal groups, especially the Sinaloa Cartel, often seek to monopolize the entire vertical supply chain. Fisheries provide a prime example.64 Beyond merely demanding a part of the profits from fishers as extortion, the criminal groups dictate to legal and illegal fishers how much the fishers can fish, insisting that the fishers sell the harvest only to the criminal groups, and that restaurants, including those catering to international tourists, buy fish only from the criminal groups. Mexican organized criminal groups set the prices at which fishers can be compensated and restaurants paid for the cartels’ marine products. The criminal groups also force processing plants to process the fish they bring in and issue it with fake certificates of legal provenance for export into the United States and China. And they charge extortion fees to seafood exporters. They also force fishers to smuggle drugs.65

Mexican criminal groups’ increasing territorial and economic power, brazen violence, takeover of legal economies in Mexico, and the impunity they enjoy raise significant questions about near-shoring to Mexico as a derisking strategy for China. Under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and previously the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Mexico became a crucial trading and economic partner of the United States. The two countries and Canada’s economies, businesses, and people have greatly benefited from North America’s economic integration. Many more integration benefits can yet be realized.

Yet will further economic integration be severely undermined by the lack of rule of law in Mexico? What risks are there in intensifying economic jointness if an economy is increasingly penetrated by criminal actors? What kind of supply-chain, legal, and other liabilities and risks are there for U.S. companies operating in Mexico or with Mexican counterparts amid a collapsing rule of law? Already, Mexican criminal groups regularly shut down major highways and even critical arteries and border crossing to the United States.66 Trucks with goods are increasingly hijacked on Mexican highways.67 Yet many Mexican companies cannot afford to pay for private security companies to protect their cargo and facilities.

Significantly improving rule of law in Mexico is essential for increasing economic integration and near-shoring.

Mexican criminal groups are also expanding into fishing outside of Mexico.68 There have long been suspicions about the extent to which Latin American fishing fleets are also engaged in the smuggling of drugs such as cocaine into the United States.69 The penetration of legal fisheries by Mexican cartels further facilitates their drug smuggling enterprise.

Similarly, massive Chinese fishing fleets have long engaged in illegal fishing, sometimes devastating marine resources in other countries’ exclusive economic zones. However, there are good reasons to be concerned about the possibility of the growing involvement of Chinese fishing ships in drug trafficking, compounding the extensive problem of Chinese cargo vessels carrying contraband such as drugs and their precursors as well as wildlife.70 Moreover, such Chinese fishing flotillas or individual vessels operating around the Americas and elsewhere in the world may carry spy equipment collection intelligence for China.

Russian intelligence operatives’ high and increasing presence in Mexico is also concerning.71 Beyond spying on the United States, they could establish relations with Mexican criminal groups and seek to leverage them for actions against the United States in exchange for a safe haven in Russia.

Would the Mexican cartels risk further provoking the ire of U.S. law enforcement? CJNG’s hallmark has all along been its lack of restraint; its signature brand is to be more brazen, audacious and violent than its rivals.72 The older leadership of the Sinaloa Cartel has been calibrated in its violence and provocation of governments and sensitive to redlines.73 But not so the younger leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel. At least until recently, this younger generation, the Chapitos, did not exhibit such restraints. While seeking to “create streets of junkies” in the United States, they showed stunning indifference to the ire of U.S. law enforcement by fueling the epidemic of death in the United States, as U.S. Department of Justice indictments of Ovidio Guzmán López and other Chapitos’ operatives revealed.74

Nonetheless, even in Mexico, where the López Obrador administration has hobbled joint law enforcement operations, the effectiveness and deterrence capacities of U.S. law enforcement are far greater than those of the Mexican government. For example, the apparent decision several months ago by the Chapitos to prohibit fentanyl production in their home state of Sinaloa75 and relocate it elsewhere in Mexico may be a sign they are responding to U.S. law enforcement pressure.

Yet overall, Mexican criminal groups govern an expanding scope of territories, economies, institutions, and people in Mexico.

These profoundly pernicious developments have taken place even as public policy, not just public safety, in Mexico has become increasingly militarized. López Obrador has relied on the Mexican military for the execution and implementation of a wide panoply of governance roles. He has tasked the Mexican military with the management of ports and airports, the construction of critical infrastructure, and even of luxury apartments.76 The legislative reforms that López Obrador pushed through the Mexican Congress have accorded the revenues from these many economic projects to the Mexican military often in perpetuity. The Mexican economy is becoming militarized.

Yet these increased economic revenues have not augmented the Mexican military’s effectiveness and resolve to take on the cartels. They may even undermine them, distracting attention from public safety responsibilities. They also weaken civilian oversight of the Mexican military as the armed forces are no longer solely dependent on budget allocations by the Mexican government.

Conclusions, policy implications, and recommendations

As vast numbers of Americans are dying from fentanyl overdose and Chinese and Mexican criminal groups expand their operations around the world and into a vast array of illegal and legal economies, the United States must strengthen access to evidence-based treatment and harm reduction measures. But supply-side efforts also remain imperative.

Below I offer some policy implications and recommendations on how the United States can attempt to reinforce and anchor China’s promise of cooperation and induce Mexico to better cooperate with counternarcotics and law enforcement objectives. I also provide suggestions for what law enforcement and policy measures the United States can and should take on its own.

Reinforcing U.S.-China cooperation

To motivate China’s responsiveness to U.S. intelligence provision and reciprocal sharing, the U.S. Congress could request regular, if closed-door, reports on these aspects of cooperation.

The U.S. Congress should consider the number of arrests and extent of prosecutions by the Chinese government of Chinese criminal actors and pharmaceutical and chemical companies and brokers involved in fentanyl and precursor trafficking as an important indicator of the robustness of cooperation. The extent and consistency of China’s monitoring and regulating of Chinese pharmaceutical and chemical industries overall and the removal of websites selling synthetic drugs to criminal actors are other important signs.

The United States should continue to strongly encourage China to adopt and enforce KYC laws and punish violators. If China continues to reject the promotion of KYC laws, the United States and its global coalition partners should raise the costs of China’s KYC noncompliance by denying Chinese suppliers and industries market access, undoubtedly an expensive policy but one that recognizes the fentanyl epidemic’s immense and multifaceted costs.

Beyond KYC laws, the United States could encourage the Chinese government and Chinese pharmaceutical and chemical sectors to adopt the full array of global control standards, including the development of better training, certification, and inspection.

Globally, the United States should remain deeply engaged in discussions on how to develop enhanced special surveillance lists and monitoring and enforcement mechanisms for dual-use chemicals, as those that are not scheduled do not have to be declared in exports.

Reinforcing China’s willingness to engage bilaterally and multilaterally in AML cooperation remains important. Bilaterally and multilaterally, China should be incentivized to adopt more robust anti-money laundering standards in its banking and financial systems and trading practices and apply them systemically in counternarcotics and anti-crime efforts, not merely selectively regarding capital flight from China.

Expanding U.S. and multilateral engagement with China about mounting appropriate controls on tranquilizers such as xylazine and emerging synthetic opioids such as nitazenes, currently poorly regulated and monitored in China, is crucial. And China’s responsiveness should be another measure of cooperation.

Certainly, these measures should strongly inform whether and when China will be removed from the Majors List.

The United States should continue developing packages of leverage on Chinese actors and when appropriate continue with its effective policy of denying U.S. visas.

The United States should not reduce its criticism of China’s unofficial police stations abroad.77 Although China labels them a legitimate law enforcement activity, the United States and other countries appropriately consider them an illegal tool for monitoring and repressing the Chinese diaspora.78

In anticipation of possible hitches and backsliding in China’s cooperation, the United States should strengthen multilateral efforts within the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats. It should concentrate on mobilizing a subgroup of countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific region and include methamphetamine in the portfolio of actions. Many countries there are experiencing large increases in methamphetamine use (and its associated high morbidity effects) and are frustrated with China as a source of meth pre-precursors and Chinese drug networks as the meth trafficking vectors.79 Many of the practices and policies suggested above as key measures of the quality of China’s cooperation double up for meth trafficking controls. China is very focused on not losing influence in Southeast Asia and the Pacific region and a joint initiative between the United States and the region on drugs will help motivate China to engage in responsive and responsible law enforcement cooperation.

Such a line of effort within the Global Coalition and beyond would help the United States and its partners to send coordinated messages to push Beijing in a preferred direction on law enforcement efforts. If China’s promised counternarcotics cooperation does not robustly materialize or weakens over time, once again raising the reputation costs for China of its law enforcement inaction will be important, especially as China prides itself on being a global counternarcotics leader.

Inducing cooperation from Mexico

U.S. counternarcotics and law enforcement bargaining with Mexico is gravely constrained by the U.S. reliance on Mexico to stop migrant flows to the United States. If the United States implemented a comprehensive immigration reform that provided legal work opportunities to those currently seeking protection and opportunities in the United States through unauthorized migration, it would have far better leverage to induce meaningful and robust counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation from Mexico. The United States would thus be better able to save U.S. lives. Nonetheless, even absent such reform, the United States can take impactful measures.

In its law enforcement engagement with the Mexican government, the United States should prioritize:

- Continuously shutting down Mexican pharmacies that sell fentanyl- and methamphetamine-adulterated drugs and investigating, dismantling, and prosecuting the networks that operate them.

- Not merely busting laboratories and seizing drugs, but actually dismantling drug trafficking networks, particularly their middle-operational layers that are hard to recreate and the removal of which significantly hampers the ability of criminal groups to operate and smuggle contraband.

- Supporting Mexican prosecutorial actions against criminal actors.

The United States should also continue to seek the restoration of joint U.S.-Mexico law enforcement operations inside Mexico, such as the consistent presence of U.S. law enforcement officers during interdiction raids. It should also continue to request that Mexico systematically shares seized drug samples with U.S. law enforcement agencies. Such presence would help Mexico’s credibility after revelations of how it manipulates law enforcement action data.

The U.S. Congress and executive branch must strongly condemn actions by the Mexican government that threaten the freedom of the press and jeopardize the safety of journalists, especially when they are U.S. citizens. The U.S. government should ensure that such actions by the Mexican government will not be repeated.

The arrival of a new government in Mexico at the end of 2024 may provide opportunities for such strengthened cooperation.

In the continued absence of such cooperation, the United States has various policy tools to consider.

Some U.S. lawmakers have proposed designating Mexican criminal groups as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO). An FTO designation would enable intelligence gathering and the conduct of strikes by the U.S. military against drug targets in Mexico, such as some fentanyl laboratories in Mexico or visible military formations of Mexican criminal groups, principally CJNG.

However, such unilateral U.S. military actions in Mexico would severely jeopardize relations with our vital trading partner and neighbor. Calls for U.S. military strikes against fentanyl-linked targets in Mexico have already been condemned by Mexican government officials, politicians, and commentators.

Meanwhile, the number of available targets in Mexico would be limited. Most Mexican criminal groups do not gather in military-like visible formations. Many fentanyl laboratories already operate in buildings in populated neighborhoods of towns and cities where strikes would not be possible due to risks to Mexican civilians. Moreover, fentanyl laboratories would easily be recreated, as they already are.

Nor would the FTO designation add authorities to the economic sanctions and anti-money laundering and financial intelligence tools that the already-in-place designation of Transnational Criminal Organization carries. The latter designation also carries extensive prohibitions against material support.

Additionally, an FTO designation could limit U.S. foreign policy options and measures. Clauses against material support for designated terrorist organizations have made it difficult for the United States to implement non-military and non-law-enforcement policy measures in a wide range of countries, such as providing assistance for legal job creation or reintegration support even for populations that had to endure the rule of brutal terrorist groups. The FTO designation could also hamper the delivery of U.S. training, such as to local police forces or Mexican federal law enforcement agencies, if guarantees could not be established that such counterparts had no infiltration by criminal actors.

To be in compliance with material support laws, the United States and other entities must guarantee that none of their financial or material assistance is leaking out, including through coerced extortion, to those designated as FTOs. Yet such controls would be a significant challenge in Mexico where many people and businesses in legal economies have to pay extortion fees to Mexican criminal groups. The attempted controls could undermine the ability to trade with Mexico, as many U.S. businesses would not be able to determine whether their Mexican trading or production partner was paying extortion fees to Mexican cartels, and thus guarantee that they were not indirectly in violation of material support clauses.

Nonetheless, encouraging a far stronger rule of law in Mexico is crucial for sustaining and augmenting near-shoring to Mexico.