The one-minute version of this case study

- Southern West Virginia is leading a bold transition from coal to clean energy. The Appalachian Climate Technology (ACT Now) Coalition is unique among Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) awardees not only for receiving the largest rural grant, but also for being one of the few coalitions led by grassroots, community-based organizations. Anchored in Charleston and Huntington, the ACT Now Coalition represents 21 counties in Southern West Virginia, all of which have the highest levels of coal dependency in the nation and were severely impacted by the national decline in coal production. For example, in Boone County, half of all residents worked in coal mines in 2008; by 2016, total employment had dropped by 80%. Today, the region is left with an abundance of abandoned mines with significant environmental implications, but it also has an emerging renewable climate technologies cluster as well as key assets that position it to be a global leader in clean energy.

- The region’s core challenge—and opportunity—is creating pathways for sustainable prosperity that directly benefit West Virginians. Southern West Virginia has suffered not only from coal’s decline but also from the targeted deployment of opioids that made the region ground zero for the national opioid epidemic. Patterns of persistent poverty, depopulation, and low labor force participation have stifled recovery, especially in the most remote, rural communities. The recent passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act have bolstered momentum for West Virginia’s clean energy sector, but the region must activate and deploy new partnerships and resources to support sustainable, inclusive growth.

- The BBBRC is helping drive a just transition with catalytic federal investment. The ACT Now Coalition’s $63 million BBBRC strategy is the story of a rural, coal-impacted region affected by persistent poverty working to transition its industry and workforce to clean energy and, more broadly, from an extractive economy toward one of shared, sustainable pathways for prosperity, designed by and for rural residents.

- Rural and distressed communities can build modernized, inclusive institutions and partnerships to uniquely benefit from large-scale federal investment. This case study explores the design and implementation of the ACT Now Coalition’s portfolio of investments in the region’s physical and civic infrastructure, including on-the-job workforce training, the co-creation of community-based resilience plans, a concerted effort to convert former mine lands to sustainable lands, and the construction of new facilities to spur renewable energy technology and workforce development. It offers lessons on how rural and distressed regions can build the capacity, relationships, and systems necessary to effectively deploy resources to drive prosperity.

Before reading this case study: What is the Build Back Better Regional Challenge?

This brief overview of the program provides useful context before reading this case study.

In July 2021, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) launched the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) through a Notice of Funding Opportunity that outlined a two-phase competition.1 Through its Phase 1 activities, the EDA issued an open call for concept proposals that outlined a high-level vision for a “transformational economic development strategy.” The thesis was that regions would identify an industry cluster opportunity; design “3-8 tightly aligned projects” to support that cluster; build a coalition to “integrate cluster development efforts across a diverse array of communities and stakeholders”; and ensure that these collective efforts advance equity by supporting economically disadvantaged communities.2

In Phase 1, 529 coalitions submitted high-level concept proposals that outlined a vision for the cluster, a high-level description of potential projects, and the key institutions involved in the coalition. After receiving Phase 1 concept proposals, the EDA undertook two months of review to determine which coalitions would be awarded $500,000 technical assistance grants and invited to apply for Phase 2 funding. Those resources enabled a hyper-intensive planning sprint between December 2021 and March 2022. During this period, each of the 60 finalist coalitions expanded their five-page concept proposal into an overview narrative and project proposals that outlined their approach, key assets and institutions, the portfolio of projects and their expected outcomes, and matching resources to complement the EDA grant.

Ultimately, the 60 coalitions submitted funding requests well beyond the BBBRC’s $1 billion allocation. The average Phase 2 funding request submitted to the EDA was approximately $75 million, while the average award amount available in the competition budget was approximately $50 million. Given this gap, in May 2022, all 60 applicants were offered the opportunity to prioritize funding through a budget request reduction process after applications were received. Then, an Investment Review Committee (IRC) assessed all completed applications and made recommendations. In some cases, the EDA ultimately selected a subset of component projects for funding or funded component projects at a reduced level, requiring applicants to modify projects during the award process. In September 2022, the EDA selected 21 of the 60 coalitions for implementation awards, ranging in size from $25 million to $65 million, to be spent over a five-year period.

Background

For the past century, extraction has shaped Southern West Virginia’s development—first from the environmental, economic, and human toll of coal and energy production and then from the targeted deployment of opioids that made the region ground zero for America’s opioid epidemic. As the region seeks to rebuild from the dual disruptions of industry decline and the widespread loss of human life, it is choosing a different—and bold—path forward: transforming Southern West Virginia’s coalfields region into the world leader in climate resilience and clean energy technology.

Between 2008 and 2015, Southern West Virginia became the epicenter of the nation’s coal decline, seeing its total coal production drop by 60%. While a myriad of factors led to the decline of coal production nationwide—including reductions in the cost of natural gas, heightened regulatory environments, and weak international demand—Central Appalachia was the hardest-hit region in the nation.

Within Central Appalachia, the 21 counties that comprise Southern West Virginia’s coalfields region were disproportionately impacted. For instance, in 2008, half of all residents in Boone County worked in coal mines; by 2016, its total employment dropped by 80%. Today, there are fewer than 12,000 coal mining jobs remaining in West Virginia.

The cascading economic, environmental, and human effects of coal’s decline are still unfolding. After rebounding from unemployment at the height of the decline, West Virginia still has one of the lowest labor force participation rates in the nation, is one of the poorest states (with a poverty rate of 16.8%, and higher rates in coal-impacted and rural counties), and has lost a higher share of its population to out-migration than any other state in the nation. The outsized impact of the opioid epidemic has only worsened these hardships, as West Virginia has an age-adjusted opioid overdose rate of 77.2 per 100,000 (compared to 24.7 per 100,000 nationwide).

The opioid epidemic is directly linked to a sense of economic hopelessness—people feeling trapped in a place with no hope for a brighter future. Then there's the role of the drug companies. We were taken advantage of. As a region, it took us generations to get here, and hopefully it only takes one generation to get where we want and deserve to be.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

The environmental impact of coal extraction has also left a persistent physical mark on Southern West Virginia. There are more abandoned coal mines in West Virginia than anywhere in the country (the majority of which are in rural areas in the southern region), and approximately 30% of all West Virginians live within a mile of an abandoned mine site. These abandoned mine sites are eroded, unable to be used for vegetation or productive uses, and pose health and safety risks for residents due to water pollution, gas leaks, mine fires, flooding, and landslides.

Yet Southern West Virginia also has significant environmental assets that position it to be a global leader in clean energy, with the right focus and investment. Appalachia—sometimes referred to as “the lungs of North America”—is one of the three most important ecosystems globally for climate change mitigation and carbon capture. Moreover, West Virginia’s history as an energy state, its industry-trained workforce, and its positioning to key rail, highway, river, and air transit provide the opportunity to build off its extensive natural assets.

Indeed, a nascent renewable climate technologies cluster is emerging in West Virginia. In 2022, the state had 17,959 clean energy jobs—more than its total number of coal jobs—and was one of the three states that added the highest number of clean energy jobs according to the Department of Energy, alongside California and Texas. There is also political momentum among key state and federal leaders to grow the cluster, with West Virginia Speaker of the House Roger Hanshaw recently saying, “West Virginia’s transition from coal to clean energy is the only path for prosperity.” The passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act—which seeks to catalyze significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and drive down costs for clean energy technologies—have only bolstered this momentum.

To harness the current moment—and help repair an economy, place, and people impacted by the decline of coal jobs and associated socioeconomic disruptions—grassroots West Virginia leaders are partnering with key institutional and industry leaders to scale the region’s climate technology cluster and transform 21 Southern West Virginia counties into a global hub of climate resilience, green innovation, and clean energy technology jobs. This mission, codified in the Appalachian Climate Technology (ACT Now) Coalition’s BBBRC proposal, presents a bold plan to address the root causes of the region’s poverty and create new pathways for shared, sustainable prosperity—and, importantly, to do so in trusted partnership with directly impacted West Virginians.

We're demonstrating that we can create jobs and bring meaning and dignity back to the communities who for many, many years mined the coal and built the roads that carried the trucks that fought wars. And for a period of time, we allowed ourselves to be told we ‘didn't belong’ anymore. Now we're back at the table and we're helping chart the course for the next chapter—not only for our state, but for our nation.

Brad Smith, president of Marshall University

Coalition formation

This section explores how leaders from community-based organizations, higher education, government, and industry came together to form the ACT Now Coalition, develop a portfolio of projects for their BBBRC application, and ultimately decide on eight equity-focused projects that, together, lay the foundation for West Virginia’s just transition from coal to clean energy technologies. ACT Now’s formation, in particular, benefited from a long history of collaboration and trust among these cross-sectoral actors, often forged in the hardship of industry decline and the opioid epidemic, and the unique dedication to place that many West Virginians feel to their state and region. The coalition’s project portfolio will be of interest to rural leaders across community development, economic development, workforce development, and higher education who are trying to repair economies severely impacted by industry decline, poverty, depopulation, and capacity challenges.

The origins of the coalition

The ACT Now Coalition is unique among BBBRC awardees not only for receiving the largest rural grant, but also for being led by grassroots, community-based organizations. In many ways, the coalition had been forming organically for around a decade—forged during the hardship of the coal decline and opioid epidemic—and was ultimately solidified by a key community-based organization, Coalfield Development, in partnership with long-term grassroots partners such as the West Virginia Community Development Hub and Generation West Virginia, as well the region’s two largest municipalities (Charleston and Huntington) and major universities, West Virginia University (WVU) and Marshall University.

In 2010, Brandon Dennison founded Coalfield Development as a “totally volunteer, grassroots effort” out of an old apartment building in Wayne, W.Va. (population 1,441). Born and raised in the coalfields region, Dennison came up with the idea for Coalfield Development’s place-rooted workforce development model while on a volunteer trip to a rural coal county, Mingo County, where he saw unemployed residents walking around with tool belts, asking for work.

Our economy was so distressed that we had young people who wanted to work literally just wandering around the streets hoping to find just a couple hours’ worth of under-the-table cash economy work. I just know that we're capable of so much more—we have so much more to offer as a state and as a region.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

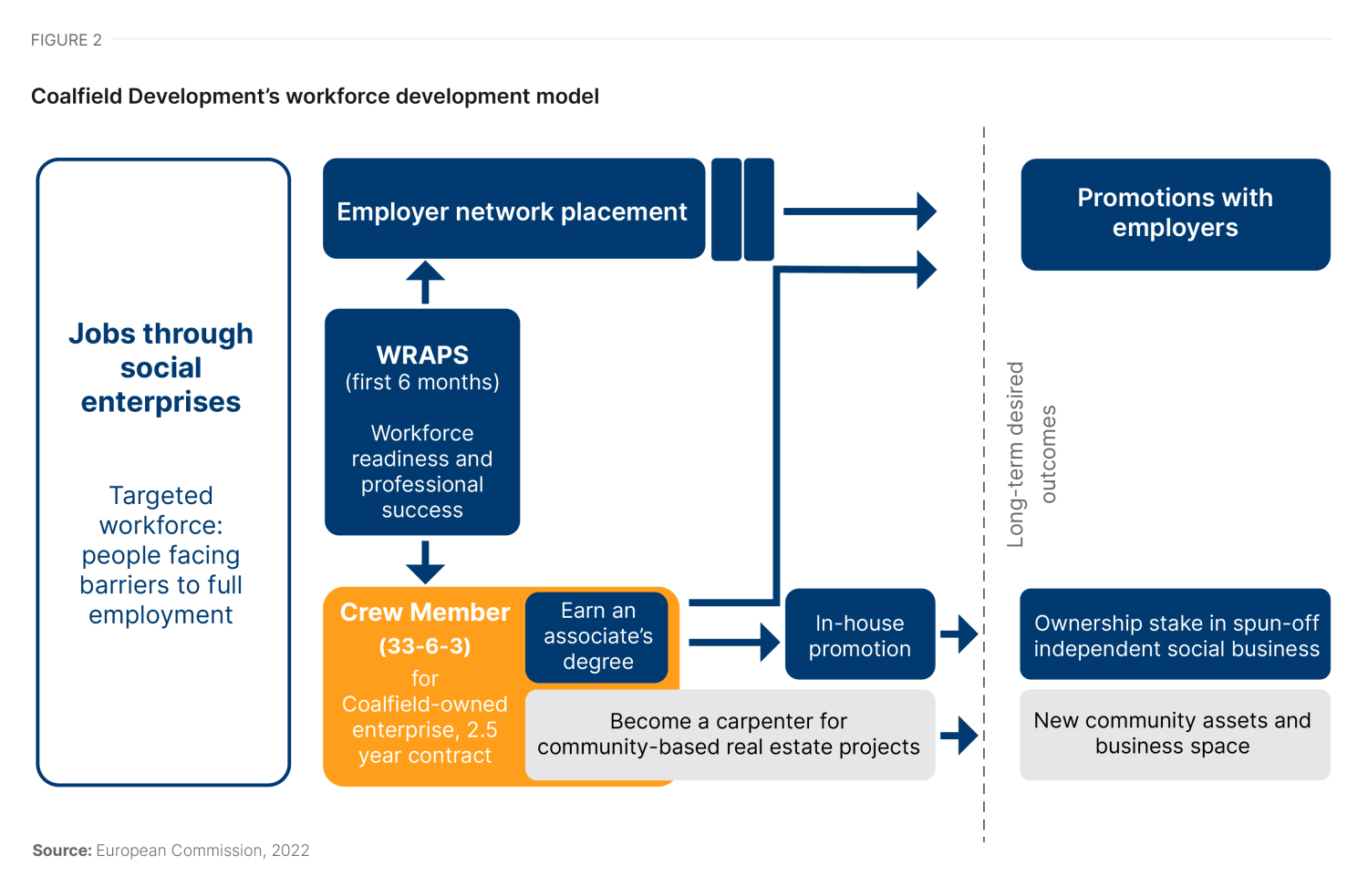

Upon returning to Wayne, Dennison started Coalfield as an on-the-job training model to hire unemployed and under-employed West Virginia workers to construct energy-efficient affordable housing. Coalfield’s 33-6-3 model (Figure 1) is designed to create a sustainable path forward for coal-dependent economies by focusing on the “human element” of workforce development in addition to hard skills—providing trainees with 33 hours of paid work, six hours of higher education (toward an associate degree), and three hours of personal development. For those with higher barriers to employment, the WRAPS (Workforce Readiness and Professional Success) program allows for more direct training and preparation for the two-and-a-half-year “crew member” job, provided directly by Coalfield. Importantly, Coalfield’s model is explicitly designed to address Southern West Virginia’s unique barriers to equitable employment outcomes, including persistent poverty, high rates of substance use and justice involvement, and lack of generational wealth

In the 13 years since its founding, Coalfield has grown from a staff of three with a bold idea to an organization of 39 that has attracted over $100 million in new investment to coal country and grown 72 new businesses (as of January 2023). Their 33-6-3 workforce development model has proven effective in employing a workforce impacted by both wealth extraction and the trauma produced by substance abuse and incarceration.

At the same time that Coalfield was scaling its model and growing its capacity in the region, a new group of place-based, grassroots-led organizations were founded to address community and economic development issues in the region, including coalition partners such as the West Virginia Community Development Hub (WVCDH) and Generation West Virginia. WVCDH, founded in 2009 by a small group of community development professionals, is a statewide community development organization aimed at addressing systemic challenges for rural development from the bottom up, including through local coaching, capacity-building, and technical assistance in co-creating community-led master plans. Generation West Virginia is also a statewide organization, focused primarily on workforce development aimed at retaining, training, and placing young West Virginians in good jobs. All three of these grassroots organizations received early seed funding from the regional Benedum Foundation in a concentrated effort to “lift up young Appalachian leaders and intermediaries in a place that’s very disconnected from not only regional economies, but also from local locally owned wealth.”

As part of this burgeoning growth of grassroots capacity, Coalfield and WVCDH began partnering closely in 2013 to facilitate an “Abandoned Properties Coalition” aimed at identifying new productive uses for vacant and abandoned buildings in the state. Two years later, Coalfield, WVCDH, and other organizations in this emerging grassroots nonprofit network had the opportunity to strengthen collaboration with each other through the Obama administration’s POWER (Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization) Initiative, which targeted federal resources to communities affected by job losses in coal mining, coal power plant operations, and coal-related supply chain industries. In addition to solidifying pre-existing lanes of collaboration with funding and capacity-building support, POWER also expanded these nonprofits’ experience with managing large federal grants, with some stakeholders attributing the initiative as laying the groundwork for success in the BBBRC grant.

Social entrepreneurs and nonprofit leaders were rubbing pennies together to survive, setting up offices in abandoned apartment complexes. And then, in many ways, during the Obama administration's POWER Initiative, a lot of us that had been rubbing pennies together were able to take our work to the next level because of the support we got through POWER. We were able to build our capacity to handle federal funds and we had this foundation of trust to start from that. We had had to be very scrappy and persistent to build it, but we had it.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

Outside of this community-based and economic development sector, city and regional government officials at the same time understood the public sector must collaborate differently to address the cascading and intersecting challenges posed by the ongoing effects of job losses and the opioid epidemic. Government officials in the state’s two largest municipalities, for instance, described a newfound necessity for collaboration across public, private, and civic institutions to channel limited resources to address the scale of the tragedy facing the state.

The way collaboration started in the city of Huntington was born out of tragedy. In 2014, the opioid epidemic just overwhelmed our community, and we weren't prepared for it. We didn't have the resources in place, we didn't have the institutional support to combat the epidemic and provide help…I was going out into the community saying…‘Everybody has to take ownership of this. Everybody has a role to play. Everybody has an assignment—individuals, businesses, churches, school systems, universities, medical schools.

Mayor Stephen Williams of Huntington, WV

Taken together, the development of Coalfield’s place-centered and sustainability-focused workforce model, the growing capacity of community-based nonprofits such as WVCDH and Generation West Virginia, and the necessity-based regional collaboration born out of statewide tragedy helped form the foundation for a successful coalition rooted in trust, a deep understanding of West Virginia, and a commitment to a more just, sustainable, locally serving future. This trust-based ethos is one of the defining characteristics of the ACT Now Coalition, and one that many of its stakeholders attribute as core to its success in securing the BBBRC award.

The ACT Now Coalition rose up against all odds. It isn’t easy for rural communities to put together this kind of coalition…Most of the places that I see on the list had universities or strong intermediaries in their management models, and very few were in deep rural regions. Most of the selected Build Back Better projects had lead organizations with strong balance sheets, a lot of existing staff, and robust data components...[Rural communities] in contrast are places that you could really transform. This money could be an equalizer to show incredibly transformational results in the places that haven't been receiving this kind of investment before.

Jen Giovannitti, President, Benedum Foundation

Aligning the coalition around a shared vision

When the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the BBBRC was first released in August 2021, Dennison and key partners knew that the timing and momentum could be right to achieve a bold climate resilience and economic recovery vision—one rooted in a deep understanding of the state’s assets as well as the cumulative impacts its challenges have had on its workforce. With new momentum in growing West Virginia’s clean energy jobs, the passage of federal legislation such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the collaborative groundwork laid in the years prior, the timing and opportunity for a bold climate vision seemed right.

What I think was genuinely historic about the economic cluster we all unified around was climate technology. We did that from the coalfields of West Virginia—that’s a really a bold vision. And we've stuck together around that vision.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

Importantly, at the time the NOFO was released, several major institutions in the region were debating who should be the lead for the BBBRC. While many other BBBRC applicants selected major universities as their lead, both WVU and Marshall made the unique decision to defer coalition leadership to grassroots organizations, with Coalfield serving as the coalition’s lead entity. They attributed this to the strength of the ACT Now vision and the role that the universities and municipalities could play in strengthening and supporting the capacity of the state’s nonprofit organizations.

I was in this seat, and it became clear that we had an opportunity to pull together all the various assets in the state. And Brandon [Dennison] was the orchestra conductor, as we describe it. What we realized is that each of us plays a different instrument, but we needed one piece of sheet music. And it was Brandon's goal to bring us all together and put our energy toward that one piece of sheet music, which was the ACT Now Coalition. Brandon reached out and said, ‘Let’s get the two largest municipalities, Huntington and Charleston, with the two flagship universities, West Virginia and Marshall University. Let's get these nonprofits and private industry together and let's start to talk about the problems we can solve together that we can't solve individually and go after this as one.’ And that's how we came together.

Brad Smith, president of Marshall University

Building on its strong working relationships with nonprofits, universities, and the municipalities forged in the two decades prior, Coalfield and grassroots partners convened a coalition broader than any previously seen in the southern part of the state, including community-based organizations that had been pioneering community and economic development initiatives for two decades; WVU and Marshall University; unions for carpenters, electrical workers, mine workers, and utility workers; and Black-led churches. From there, the groundwork was laid for a strong vision: West Virginia could leverage its natural and energy assets to enable a “just transition,” specifically by investing in the skills and capabilities of its people to evolve from an economy based on extraction to one rooted in climate change mitigation.

In our state—especially in the bottom third of West Virginia—that coalition had never been formed before, where all of those mayors and commissioners and city entities and the governor and all have worked together to make that happen…We were already working together in our small pockets, and I have to give Coalfield credit for pulling everybody together that had that mindset.

Bishop Charles Shaw, Huntington Black Pastors Association

Project identification and selection

After months of planning discussions, the ACT Now Coalition coalesced around a vision for the state’s climate technology cluster rooted in eight strategic goals: 1) climate change mitigation; 2) environmental justice; 3) community engagement and equity; 4) community resilience and infrastructure investment; 5) green-collar workforce development; 6) green construction and preservation; 7) locally grown entrepreneurship; and 8) locally serving technology.

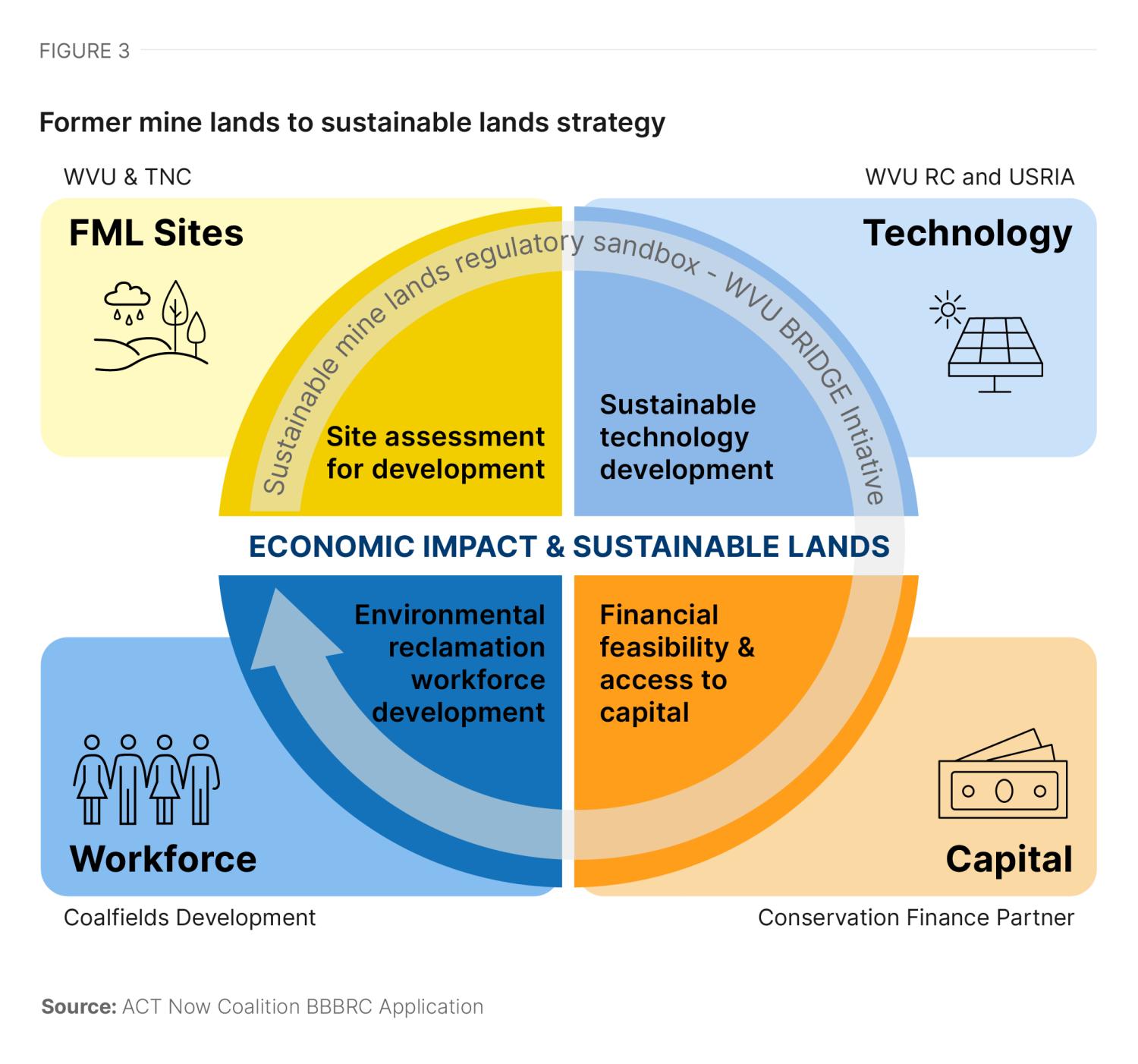

Based on these eight threads, the coalition identified eight corresponding projects in their BBBRC application and requested $75 million in BBBRC resources, with a $33 million commitment in private match funding. Recognizing the equivalent need to invest in both physical and civic infrastructure, they ultimately landed on four non-construction projects and four construction projects (Figure 3).

Taken together, these eight projects are designed to be greater than the sum of their parts, For instance, workforce development projects have been crafted to directly prepare underemployed West Virginians for clean energy jobs; construction jobs will be located in some of the most economically excluded and coal-impacted communities in the state; and community-development resilience projects (led by WVCDH) are co-located in communities with both construction and workforce development projects. These interlocking projects are presented in the overviews and in Figure 3 below.

Non-construction projects: ACT Now’s non-construction projects are together focused on supporting various aspects of the region’s workforce development ecosystem to support workers in accessing clean energy jobs, as well as building up municipal and sectoral capacity to leverage clean energy investments for broad-based benefit.

- Growing Resilient Opportunities for the West Virginia Workforce (GROW Now Workforce Initiative): GROW Now seeks to address regional barriers to equitable employment outcomes, including rurality, persistent poverty, low labor force participation, high rates of substance use and justice involvement, and lack of generational wealth. Coalfield’s model aims to do so by expanding its 33-6-3 workforce development model into different areas in the southern part of the state, offering subsidized job training, and directly employing on-the-job trainees to secure quality climate technology jobs. Generation West Virginia’s role is to expand training, job placement support, and its fellowship program to support young people’s employment outcomes in the state. Marshall University’s component is focused on building an equitable internship pipeline for the state’s southern educational institutions, while WVU is seeking to attract remote workers to the state. This project represents a coordinated effort to align and scale the various job, training, placement, and retention programs across the coalfields region to best meet the unique needs of West Virginia workers.

- Community and Business Resilience Initiative (CBRI): CBRI aims to support 16 coal-impacted, distressed communities in the 21-county region with equity-focused planning and pre-development support to co-create a community-based resilience plan that will help localities leverage the state’s growing clean energy sector for community benefit. In community selection, CBRI prioritizes equity and seeks to overlap with geographies in which construction projects will be located.

- RePower Appalachia Renewable Energy Market Development (RePower): RePower seeks to de-risk green investments in the region by providing market analyses for emerging industries, training and apprenticeship programs, and pre-development supports for “shovel-ready” projects, as well as facilitating capital investment into the clean energy sector.

- Former Mine Lands to Sustainable Lands: This strategy seeks to facilitate the conversion of former mine lands to their highest and best uses. This includes conducting site evaluation and pre-development technical assistance; deploying sustainable reuse technologies within former mine lands; facilitating private investment; collaborating with partners to create high-quality jobs through workforce development; and addressing regulatory constraints for reuse.

Construction projects: ACT Now’s construction projects are centered around building out the physical infrastructure needed for a just transition to clean energy, including through new logistic hubs, technology and training centers, and place-based workforce development anchors.

- Black Diamond Sustainable Development Logistics Hub: This construction project will redevelop an anchor brownfield site in Wayne County as a campus for climate-resilient entities to set up operations, expand, and achieve logistical efficiencies. Initial entities will include West Virginia-based solar company Solar Holler, which will occupy an administrative and logistics hub, as well as the ReUse Corridor, which will establish a new commercial base in recycling, reuse, and sustainable materials management.

- Learning, Innovation, Food, and Technology (LIFT) Center: This construction project will rehabilitate a historic coal factory in Charleston’s East End neighborhood to be a technology hub for climate resilience enterprises. These enterprises will include East Edge, an earn-and-learn training facility in Charleston (modeled after Coalfield’s West Edge flagship), a new Marshall University Battery Research Institute, and multiple startups dedicated to renewable energy technologies.

- H-BIZ Green Manufacturing Hub: This construction project will support the redevelopment of 50-plus acres of cleaned brownfields on the ruins of a factory established 150 years ago by the Huntington city founder. Among other uses, it will host the headquarters and data center for Mountain State Fiber, a veteran-owned regional technology leader deploying open network, high-speed broadband in Southern West Virginia.

- Just Transition Center: This construction project will redevelop a 25,000 square foot, four-story building in Logan, W.Va.—known locally as the “old Miner’s Academy”—to be a Just Transition Center that will train a future workforce of biomanufacturers, technologists, solar installers, and green-collar contractors, and eventually host the GROW Now and RePower project components.

With this proposed project portfolio, ACT Now was selected as one of the BBBRC’s 60 Phase 2 finalists (out of 529 coalitions competing for this designation in Phase 1). Since Phase 2 funding requests exceeded the BBBRC’s available resources, the EDA gave all Phase 2 finalists, including ACT Now, the opportunity to reduce their budgets. The group submitted a revised proposal for all eight projects, and was provided a $62 million award from the EDA.

We could have cut one big construction project and got down to our number we needed to be at. But we stuck together and we said, ‘We'll all take a reduction across all the projects.’ At the end of the day, we had all settled on a very sound strategic balanced strategy of four construction and four non-construction projects…We felt it was important to us to stick together and to feel the pain together and to keep all the projects in the mix.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

Based on their commitment to maintaining a cohesive project portfolio and coalition, the ACT Now Coalition has spent the last year implementing its $62 million in BBBRC funding toward its eight projects—keeping “the whole” of the strategy together through mutual support across project leads and partners of varying capacity levels.

Embedding equity into the strategy

One of the EDA’s top priorities for allocating BBBRC funds was equity, which the Biden administration defines as “investments that directly benefit 1) one or more traditionally underserved populations, including but not limited to women, Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders or 2) underserved communities within geographies that have been systemically and/or systematically denied a full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic prosperity such as Tribal Lands, Persistent Poverty Counties, and rural areas with demonstrated, historical underservice.”

The ACT Now Coalition was, in many ways, rooted in equity. Operating in one of the most persistently poor regions in the nation, the work of Coalfield and its partner organizations had long been committed to rebuilding the state’s dislocated workforce and help it transition it from an extraction economy to a more just and sustainable future. Embedded within the 33-6-3 model, for instance, is a recognition of the socioeconomic hardships that dislocated workers face—including substance use recovery and the barriers posed by criminal records—and built-in time for personal healing, development, and growth. The West Virginia Community Development Hub’s community-centered planning model also prioritizes equity and is stewarded by an Equity Advisory Team that seeks to ensure the Hub is intentional about being representative of the diverse communities they serve across the state, including by hiring and retaining diverse staff and creating a full-time Racial Equity Fellowship. Generation West Virginia has also set equity goals for its programing, committing that at least 50% of their workforce trainees be from groups that are underrepresented in technology.

More than half of trainees are in recovery from substance use disorder, nearly a quarter are justice system involved. These are highly marginalized populations. They're on a blacklist for employers. Even if they get clean, getting back in the workforce is very hard—let alone with a good, decent-paying job with benefits.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

In terms of the coalition composition, half of ACT Now members are from “persistent poverty” communities, meaning communities that had poverty rates of 20% or more in 1990, 2000, and 2010. Moreover, the coalition was intentional about ensuring that lower-capacity partners in more remote rural areas were included as part of the effort, so that they could eventually be leads on federal grants themselves.

We did not want just the big dogs that already had capacity to be the ones to soak up all the money for the grant…We made sure to pull in municipalities from more rural, less populous counties. That was really important to the coalition. And we also made sure to pull in smaller organizations to be a partner, even if they never had a federal grant. We're going to work together to help build capacity so the next time around, they can be the direct grantee.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

Finally, in one of the least racially and ethnically diverse states in the nation, the coalition prioritized racial equity, in part through its partnerships with Black churches—with paid stipends for pastors’ participation in connecting members of their churches to workforce development programs—to ensure that residents of color were directly recruited into GROW Now initiatives.

They've recognized the value of our time by giving that stipend. Economically, that's resolving some issues. And when you decide to give a stipend, you say, ‘I value what you bring, your experience, and the fact that you're going to be there.’ And when you put value on people, the result is always better.

Bishop Charles Shaw, Huntington Black Pastors’ Association

Implementing the strategy

Early successes and challenges

ACT Now’s early implementation lessons demonstrate the importance of trust and place-rootedness as essential ingredients of equity-focused development in the coalfields region—providing a promising case study for how the leadership of grassroots organizations (in partnership with higher education institutions, municipalities, and industry) can steward successful regional cluster development initiatives. It also points to preliminary findings regarding the catalytic impact that federal investment can have in persistent poverty communities that have long been disconnected from private, public, and civic investment.

Of the implementation activities underway across ACT Now’s eight funded projects, the non-construction projects have seen the most rapid progress. In five key priorities in particular (presented below), these projects have achieved early successes while overcoming significant barriers that often make economic, community, and workforce development initiatives more difficult in distressed and remote rural regions.

- Scaling and aligning the region’s workforce development ecosystem: ACT Now’s workforce development strategies—bucketed under its GROW Now project and led by Generation West Virginia, Coalfield, Marshall University, WVU, High Rocks, Carpenters’ Union, WorkForce West Virginia, and various community colleges—have secured key early wins in scaling equity-focused workforce programming aimed at addressing the employment barriers posed by persistent poverty, rurality, substance use disorder, and justice system involvement.

For example, since being awarded the BBBRC grant, Coalfield tripled the number of people served by its WRAPS program, hired 11 new staff to support workforce programming, and expanded their recruitment strategies to prioritize racial equity and strengthen partnerships with Black pastors. Moreover, Coalfield and High Rocks were able to secure a Department of Labor Workforce Opportunity for Rural Communities (WORC) grant to compensate their workforce trainees (which they could not use EDA funds for). Generation West Virginia, whose workforce model focuses on placing young West Virginians in software development jobs in the state, has also been able to scale its training programs (such as Career Connector), expand industry partnerships, increase staffing, and secure a WORC grant to pay workforce trainees.

While GROW Now partners described several challenges in the first year of implementation—particularly in hiring and staffing-up internally, identifying funding to pay for workforce trainees’ time, and navigating broadband access issues—they have made significant progress in aligning workforce development programming across the region, expanding organizational capacity, and scaling their efforts to serve a greater number of underemployed workers in the state.

West Virginia has to be able to support people in finding good jobs or people won't be able to live here—and that means the younger generation can't live here either. As people grow up, these jobs won't exist anymore if we don’t get people to start filling them now…A new program we started based on hearing all these employers saying there are not any young people in West Virginia for their jobs and all these young people saying there aren't any jobs —has really grown since the BBBRC. We hired someone full time who is running that program now, who's doing a really great job. And he's been here less than a month and already, five new people have been placed through the program and we have 21,000 people looking at that program every month.

Alex Weld, executive director of Generation West Virginia

- Helping distressed localities build resilience through community-led planning: ACT Now’s Community and Business Resilience Initiative—led by WVCDH in partnership with Advantage Valley, New River Gorge Regional Development Authority, West Virginia Brownfields Assistance Centers, and local municipalities—selected and began convening its first cohort of coal-impacted distressed communities to engage in equity-focused “community-based resilience plans.” Last year, WVCHD received applications from municipalities across the region and ultimately selected six communities of different sizes to participate in the program, including: the West Side neighborhood of Charleston, the Fairfield neighborhood of Huntington, the city of Ronceverte, the city of Princeton, and Webster County. Importantly, two of the selected communities—the West Side and Fairfield—are formerly redlined, majority-minority areas and overlap with the location of ACT Now construction projects.

The six CBRI teams began meeting in August 2023 and have already begun to foster a new sense of collaboration among municipalities across the region while receiving technical assistance from WVCDH. Through this technical assistance, they will receive small business coaching, pre-development for a sustainable green development project aimed at revitalizing the local business districts, and assistance on how to apply for and receive federal, state, and philanthropic funding. Next year, WVCDH plans to select 10 more communities, and is already working with some communities that applied for the first round to build their capacity to better participate in the next round.

We launched our first group training session in August. That was met with just so much excitement, so much energy from community members and partners. It gave everyone the opportunity to see what the community teams were thinking and to actively communicate with the other community teams. I think in West Virginia, and Appalachia in general, we talk about working in silos a lot. Sometimes that's a community silo, sometimes that's an institutional silo. But at these group sessions you see everyone truly asking for more communication. Asking, ‘How do we keep talking to one another? How do we keep these ideas? How do we leverage one another's resources because we're all the southern part of the state?’ Seeing that desire for collaboration was just exciting all around. And starting from there, we were able to introduce the teams to partner services, entrepreneurial support and development, coaching services, startup funds, and different revolving loan capital funds.

Brianna Hickman, Community and Business Resilience Initiative Project Director

- Laying the foundation for a just transition: While all coalition projects are rooted in principles of environmental sustainability and economic justice, two projects in particular have started to make significant in-roads in securing early, visible wins toward this goal. The Appalachian Solar Finance Fund (part of the RePower project), for instance, has seeded 46 new solar projects in the state and is continuing to accelerate the number of jobs it creates and communities it supports.

The Former Mine Lands to Sustainable Lands project—led by WVU, in partnership with Coalfield, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, and the Nature Conservancy—has also achieved significant early wins in its mission to convert former mine lands to their “highest and best uses.” Last year the WVU team completed a “Zillow” of former mine lands, which provides a searchable census of former mine lands in the state, who owns them, and what their best use could be (housing, regenerative agriculture, recreation, etc.). Also, WVU is in the process of selecting 10 demonstration sites as pilots for their redevelopment strategy to convert mine lands into sustainable lands. While they are facing a larger structural challenge with difficulties in land acquisition and ownership, there is significant support at the university to sustain this work as a permanent Sustainable Lands Center within WVU.

One of our greatest liabilities in our state is we don't have a ton of developable land. West Virginia is one of the most topography-rich states in the country—every county is considered mountainous. And if you flatten West Virginia, it'd be the size of Texas. It's just because of all the ridges, its Appalachian Mountains—what that means is that we don't have a ton of developable land…A Lot of these mine lands have somewhat become flat, right? Because they've been infield, not all of them, but there's some. So how do we take these potential liabilities—because they are bonded right now and you can’t get to them—and how do we turn them into assets, into developable land, whether it's for housing, agriculture, solar, wind, geothermal, recreation? That’s the matrix we’re putting together.

Danny Twilley, assistant vice president of economic, community, and asset development at West Virginia University

- Building regional nonprofit capacity: The BBBRC award has been transformational for building the capacity of West Virginia’s nonprofit sector to increase staffing, scale programming, and gain experience managing and applying for large federal grants. For instance, several ACT Now nonprofit partners recently received Department of Labor grants to bolster their workforce development strategies, and all were able to staff up and gain new connections with partners across the state beyond their traditional service areas and sectoral areas of focus. For community-based nonprofit organizations such as WVCDH that have long been disseminating best practices for rural economic and community development, ACT Now facilitated a significant expansion of their coaching, technical assistance, and planning development programming into new geographies and place types (including disinvested urban neighborhoods in Charleston and Huntington).

These successes have not come without their challenges. Four primary barriers surfaced from nonprofit grantees related to their capacity to implement the coalition’s strategies using BBBRC funds. First, they described the EDA reimbursement process as remarkably slow, with many nonprofits relaying significant challenges in maintaining ACT Now programming without reimbursement and flagging this concern as an equity barrier for future federal efforts.

Second, stakeholders described the EDA reporting requirements form as burdensome and at times repetitive, which some lower-capacity nonprofits said was hamstringing their ability to execute project work and adhere to BBBRC reporting requirements with limited staff capacity. As part of this, they reflected that expectations around the pace and scale of outcomes should look different in rural areas, given the small populations being served there relative to larger metro areas, the severe industry and workforce constraints specific to West Virginia, and the diminished civic capacity that many rural nonprofit organizations had to overcome at the front-end of the BBBRC to set themselves up for success.

Wayne, West Virginia where Coalfield started has a population of like 1,600…Most of the counties we're serving are about 20,000, sometimes less…A lot of the reviewers are in cities and they've never been to West Virginia, they don't understand the context here. Fifty new jobs in Wayne, West Virginia is transformational. But to someone in a city, they're like, why are you only create 50 new jobs? No one's created 50 jobs at once here in a decade…A lot of folks I find just are not in touch with rural reality.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

The EDA’s outcomes tracking includes both quantitative and qualitative components. Some stakeholders suggested—as does existing research on rural areas competing in federal challenges—that a stronger emphasis on qualitative indicators such as early governance and capacity wins, new relationships built, and authentic community engagement could be useful complements to quantitative metrics and weighed just as heavily, particularly during the “ramp-up” phase of early implementation.

Third, several nonprofit partners described that while the BBBRC was an incredible opportunity to scale equity-focused economic and community development programming and build their capacity for securing and managing larger federal grants, some reported significant capacity challenges during the ramp-up phase of BBBRC implementation, which temporarily reduced their ability to focus on potential new opportunities on the horizon. While this was often seen as a “good challenge to have” given the significant investment the EDA provided, it did cause some partners to report concerns about maintaining diverse funding portfolios while devoting most of their early staff time to setting up their BBBRC portfolio for success.

We don't have anyone on our staff who has the time to think about new projects or project development. Build Back Better has put us in this really interesting position. I guess not a bad position, but we are at the very top of our capacity because we have just enough money to pull off doing our work and managing all of our sub-recipients and managing all of our partnerships that come from this.

A West Virginia economic development stakeholder

Fourth, nonprofit partners identified a larger concern from the BBBRC award that could have lasting ramifications for West Virginia. While ACT Now Coalition partners described being incredibly grateful for securing one of the largest concerted philanthropic matches in the state’s history to support their vision, some coalition members reported now seeing reductions in operating support from regional philanthropies that they once relied on to operate non-EDA programming. They described a perception across the state that coalition members do not “need” further philanthropic support due to the recent influx of EDA resources, and have also seen regional philanthropic support decline during the first year of BBBRC implementation. This funding limitation has created new concerns about the long-term sustainability of ACT Now priorities given the time-limited nature of the EDA grant, but coalition members are actively co-fundraising and seeking new avenues to fill the gap. This preliminary finding is consistent with previous research indicating that matching funds requirements can place a disproportionate burden on rural and tribal places, which often have less of a fiscal buffer and less access to outside resources.

We just don't have that much philanthropic resources in the state, and they're largely tapped out with matching federal dollars. The match resources are really limited and the same funders are being asked for match over and over.

West Virginia community development stakeholder

- Motivating new statewide momentum for clean energy technology: Finally, another significant success emerging from early BBBRC implementation is one that is difficult to quantify but is foundational for achieving the coalition’s goal: a newfound sense of hope and commitment across the state to be a global leader in clean energy. ACT Now stakeholders described the new phenomenon of clean energy being slowly embraced by a broad swath of unexpected champions, from former coal miners to deeply conservative elected officials. In a state that has long struggled with setbacks rooted in extraction and exploitation, this new positive narrative has provided the state with a sense of hope, which the coalition saw as a significant win in itself.

The EDA Build Back Better grant is contributing to a positive narrative in the state. New economic development is happening, federal funding is flowing to the state, and there's a capacity on the ground to capture those funds and put them to use.

Stephanie Tyree, executive director of West Virginia Community Development Hub

Organizing coalition-wide to deliver equity

The BBBRC award helped solidify linkages between the organizations, institutions, and municipalities—some of which had been collaborating organically over the past two decades, but often without the dedicated resources needed to support a cohesive, bold, and sustainable vision for the entire southern coalfields region.

On the nonprofit side, many of the ACT Now relationships between grassroots organizations were fostered gradually over decades-long trust-building efforts forged amid the hardship of the coal industry’s decline and the opioid epidemic. The BBBRC formalized these partnerships through a significant, multi-year investment in the coalition itself, and reached a broader swath of the region’s nonprofits—particularly smaller, more grassroots organizations that may not have otherwise been able to participate in a large-scale federal initiative like this. On the university and municipality side, the ACT Now coalition fostered new collaborations across entities that had been collaborating within their own geographic boundaries but may have otherwise been seen as regional competitors, including the state’s two largest universities and municipalities.

ACT Now relies on a governance model that prioritizes equitable decisionmaking and power-sharing across members. It was operationalized by creating a formal voting mechanism for decisionmaking across the entire coalition, giving equal voting power to small grassroots organizations, universities, municipalities, and economic development groups alike. The first test of this consensus-based voting structure was when Coalfield CEO Brandon Dennison accepted a position as vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University, and after discussions about how the transition could impact the coalition, the coalition voted unanimously to keep him as its regional economic competitiveness officer (RECO). ACT Now’s consensus-based shared leadership model was an important expression of the coalition’s values of equity and justice, as it represents a true instance of power-sharing across organizations of multiple capacity levels.

We consciously and purposefully expanded the coalition to try to be equitable and inclusive and pay it forward. A lot of us…sort of took the smaller organizations under the wing. We found an obligation to do that through Build Back Better. But that introduced new voices, new perspectives, and the trust hadn't been earned. We opened ourselves up to investing a lot of time and energy into building that trust and that rapport with both partners, new and old.

Brandon Dennison, vice president of economic and workforce development at Marshall University and founder of Coalfield Development

Implications

The ACT Now Coalition’s early implementation lessons provide critical insights for rural economic and community development leaders, particularly for those seeking to chart a “just transition” from extraction economies to cleaner and more sustainable sectors. Three key insights emerge that hold relevance for policy and practice at the local, regional, state, and federal level.

- First, ACT Now demonstrates the power of homegrown, place-based models in advancing inclusive rural economic, community, and workforce development, especially when supported with the catalytic capital needed to scale.

The very success of the ACT Now Coalition itself—having secured one of the largest philanthropic matches in the state’s history and $63 million from the EDA as one of the only grassroots, nonprofit-led BBBRC coalitions—speaks to the strength of its vision for a just transition. Importantly, the groundwork for this success was laid in the decades prior through the collaborative development of homegrown, place-based economic, community, and workforce development models co-created by grassroots nonprofits to be tailored to the unique circumstances of persistently poor West Virginia counties.

Two of these place-based models hold particularly significant relevance for other rural regions seeking to more equitably and effectively grow their workforce and community development. First, Coalfield’s workforce development model, 33-6-3, is a “human-centered” training and professional/personal development program for underemployed workers—particularly former coal workers with high barriers to employment such as substance use recovery and criminal records. This model has strong potential to be adapted to other rural and coal-transitioning regions. In 2018, for instance, the World Bank highlighted Coalfield’s model as highly relevant to coal-impacted communities across the U.S., Europe, and China. The West Virginia Community Development Hub’s role as a statewide intermediary devoted to rural community and economic development has also been highlighted as a national model for “doing development differently,” and provides a concrete approach for investing in rural communities to build their capacity, tackle systemic barriers to growth, and drive systems-level change that local leaders in rural areas of all kinds can learn from and adapt to their unique local contexts.

- Second, the ACT Now Coalition demonstrates the importance of place-rootedness and trusted leadership as foundational ingredients for successful and equitable regional cluster initiatives, particularly in rural areas that have systemically been exploited and abandoned.

ACT Now partners repeatedly emphasized that their coalition’s strength stems from two primary factors: 1) the deep connection that local leaders feel to the state of West Virginia as their home and source of community; and 2) the trust and collaboration forged across organizations throughout their perseverance during the overlapping crises of coal’s decline and the opioid epidemic. By virtue of their place-rootedness and earned trust, higher-capacity organizations within the coalition prioritized equity in coalition formation and implementation by explicitly building the capacity of smaller organizations at expense of even their own success.

This early finding demonstrates the important leadership role that more grassroots, community-centered nonprofits can play in stewarding regional coalitions in communities nationwide, and indicates the value that community mediation and trust-building hold in economic development. It also reinforces findings from other rural development research that indicates one of the most critical components of rural resilience is the presence of trusted relationships, shared regional partnerships, and collective action to maximize resources, capacity, and the ability to scale effective programming in systemically disinvested rural areas.

- Third, ACT Now’s early implementation experience exemplifies the outsized potential that catalytic federal investments can have in severely disinvested rural regions, but also that the drivers and measures of success can look different in rural areas—indicating the need for flexibility in federal competitions to allow for the unique constraints of rural areas.

Many ACT Now stakeholders emphasized that the resources the BBBRC provided were a once-in-a-generation opportunity, with the potential to shape Southern West Virginia’s growth for the next 100 years. Some felt that the uniqueness of the BBBRC opportunity in rural West Virginia set the coalfields region apart from some of their larger and more well-resourced peers that more often have the resources and connections to successfully compete in large federal competitions. Indeed, ACT Now stakeholders wasted no time in leveraging this catalytic capital to significantly scale and align workforce development programming across the state, expand the capacity of the region’s entire nonprofit community development sector, and launch four transformative construction projects that physically tie all programmatic elements together.

Even with this catalytic potential, however, stakeholders’ early implementation experiences point to the need for federal competitions to acknowledge that the drivers and measures of success can look fundamentally different in rural areas compared to larger peers due to the distinct capital access, capacity-building, administrative, and human capital hurdles that uniquely affect rural areas. As researchers have noted elsewhere, federal competitions should place a high priority on qualitative assessments (both in awardee selection and post-award reporting requirements); consider making implementation time frames more flexible and longer to level the playing field for rural areas compared to larger and better-resourced metro area peers; and recognize that rural measures of success must be placed in their local context relative to the socioeconomic context of their region and the nation writ large.

Conclusion

Despite the many structural disadvantages that Southern West Virginia and other rural regions face in transitioning from extraction economies to more sustainable ones, ACT Now has swiftly demonstrated their true potential to transition the coalfields region to a new leader in clean energy technology. Though the full impact of the ACT Now Coalition’s BBBRC strategy will likely not be known for many years, its impact on the coalfields region so far has been extremely promising and demonstrates a model for justly transitioning rural communities from places with persistent poverty to those with shared, sustainable pathways to prosperity—designed by and for rural residents.

EDA case study series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publications are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or other scholars.

Brookings recognizes the value it provides in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its funders reflect this commitment.

The authors thank Alex Jones, Bernadette Grafton, Ilana Valinsky, Ryan Zamarripa, Suyog Padgaonkar, Scott Andes, and Justin Tooley from the Economic Development Administration for their insights into the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and for their guidance throughout the development of this case study. For their comments and advice on drafts of this paper, the authors also thank our colleagues Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, Mayu Takeuchi, and Tony Pipa, as well as Brandon Dennison (Coalfield Development Corporation), Stephanie Tyree (WV Community Development Hub), and Alex Weld (Generation West Virginia). The authors also thank all local leaders, community-based organizations, economic development practitioners, regional intermediaries, higher education institutions, industry representatives, and other coalition members who participated in informational interviews and site visits throughout this project, and who provided feedback on the research insights and policy recommendations detailed in this report.

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

About Brookings Metro

Brookings Metro collaborates with local leaders to transform original research insights into policy and practical solutions that scale nationally, serving more communities. Our affirmative vision is one in which every community in our nation can be prosperous, just, and resilient, no matter its starting point. To learn more, visit www.brookings.edu/metro.

-

Footnotes

- Economic Development Administration. “FY 2021 American Rescue Plan Act Build Back Better Regional Challenge Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (ARPA BBBRC NOFO).” U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better

- Ibid.