In the U.S., a person’s ZIP code significantly shapes the trajectory, quality, and length of their life. Neighborhoods are the building blocks of strong cities and regions, determining people’s access to education, jobs, clean air, and upward mobility. But far too often, they are overlooked as essential ingredients of regional and national prosperity.

When policy conversations hover only at the regional level or higher, the intersections between economic opportunity, health, public safety, and climate resilience—which converge to impact people’s lives on a hyperlocal scale—can be missed, as can the need for cross-sectoral action to address these issues. Focusing on neighborhoods allows practitioners and policymakers to target the scale at which these socioeconomic issues are concentrated and assemble the cross-sectoral coalitions needed to achieve the population-level economic and public health outcomes that form strong regional economies.

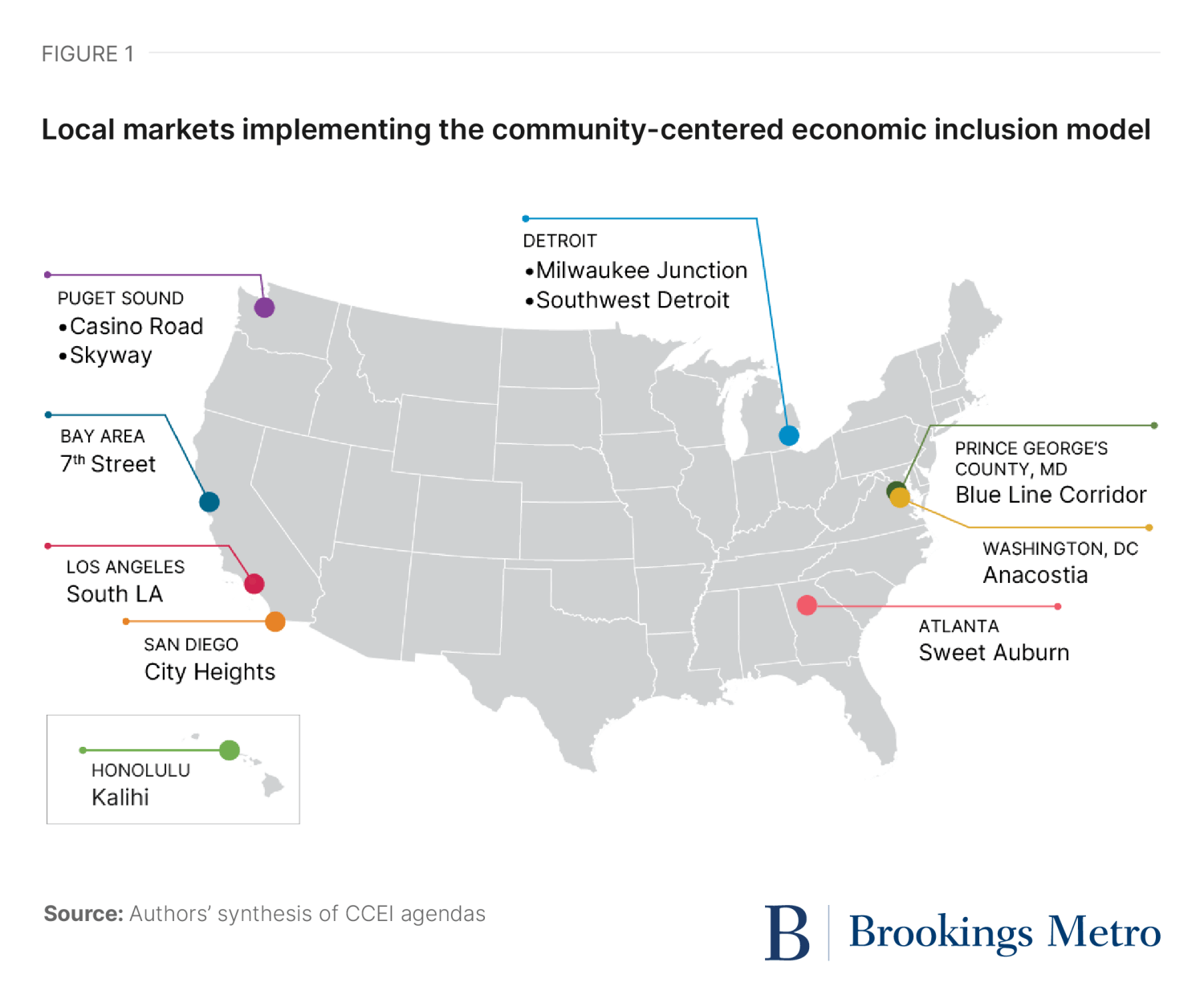

This report outlines lessons, outcomes, case studies, and recommendations from a national community-centered economic inclusion (CCEI) initiative—co-led by Brookings Metro and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) for the past five years—that embodies this theory of change and treats neighborhoods as the key setting for achieving inclusive regional outcomes. Eleven neighborhoods across six states and Washington, D.C. implemented the CCEI model (Figure 1)—each assembling a diverse coalition of community, city, and regional practitioners that aligned catalytic investments in economic development, affordable housing, workforce development, food access, placemaking, and other drivers of community well-being in historically disinvested neighborhoods.

Our findings—derived from in-depth interviews with 100 stakeholders implementing CCEI on the ground and quantitative investment data from the 11 neighborhoods—demonstrate the transformative impact that place-based models like CCEI and similar approaches can have by improving economic and public health outcomes in historically disinvested neighborhoods. But these findings also reveal a set of policy, practice, and funding barriers that must be addressed to enable these approaches to scale.

Taken together, the lessons in this report make one thing clear: To truly transform the prosperity and well-being of entire cities and regions, it’s past time to abandon top-down or “trickle-down” approaches and embrace the actionable, community-centered models that have demonstrated true promise in cities and neighborhoods nationwide.

The community-centered economic inclusion model

Developed and piloted in 2019, the CCEI model helps places “grow from within” by leveraging cross-sectoral resources to invest in local assets that generate positive economic and public health outcomes. (Figure 2; for more information, see pages 5-9 in the report)

CCEI has three distinctive elements:

- Hyperlocal scale: Using data and community engagement, CCEI targets investments in commercial or industrial districts and adjacent residential areas where economic assets cluster, but have been hampered by economic disinvestment and/or displacement pressures that prevent residents from benefiting from new growth.

Access to data helped us understand and learn a lot about the corridor. That’s been critical to get us thinking about what assets are in the corridor—because physically, when you look around, you can imagine that there’s nothing, but that’s the wrong frame of mind.

A West Oakland, Calif. stakeholder

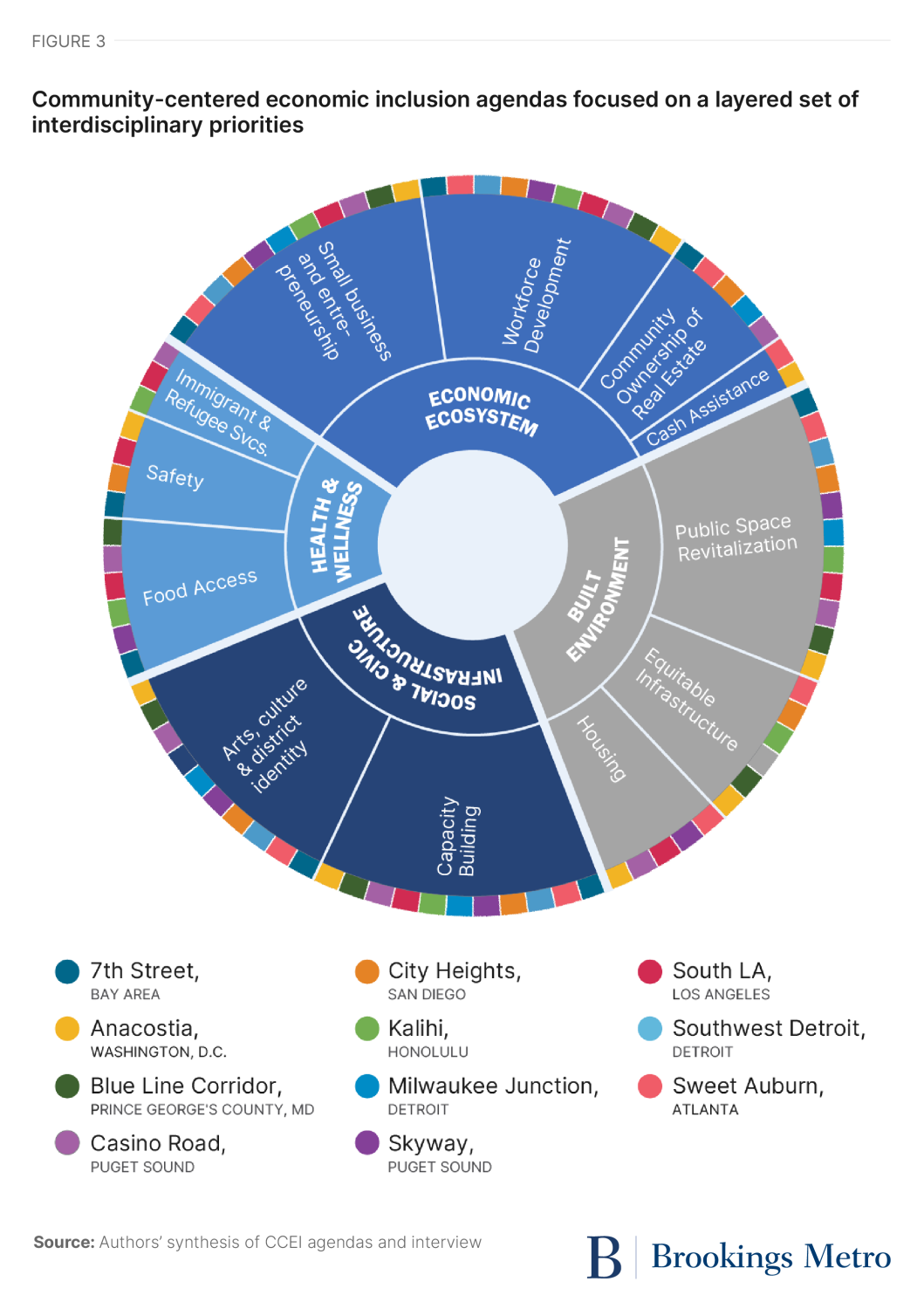

- Interdisciplinary scope: CCEI aligns investments around a set of community-defined priorities that are prime for catalytic investment—spanning the fields of economic, community, and workforce development; placemaking; and public health.

It’s always been more about the revitalization of the buildings, less about how they will work for the neighborhood. And this is different. We’ve never had a plan where we’re creating an urban agriculture ecosystem that encompasses multiple developments and where there are resources attached to it.

A Sweet Auburn, Atlanta stakeholder

- Level of integration: CCEI breaks down siloes and legacies of distrust by sharing decisionmaking power between community leaders, the public sector, and other city and regional officials.

We have this community leadership empowerment program that works to strengthen local leaders and build in individuals the capacity, skillsets, and personal leadership of how to run a community meeting, how to deescalate conflict, and how to understand the basics of the urban planning process. Because too often, the public gets involved in development when they see the cranes going up. But by that time, those decisions were made five years ago.

A Prince George’s County, Md. stakeholder

Participatory planning in Casino Road, Puget Sound | Photo credit: Ryan Berry

Vanguard CDC presents on the new Main Street designation and forthcoming small business association in Milwaukee Junction, Detroit | Photo credit: Vanguard CDC

A look across the 11 CCEI agendas reveals a diverse array of priorities spanning disciplines that reflect neighborhood assets (Figure 3; for more information, see pages 38-39 in the report). Critically, each city’s CCEI effort stressed how these multifaceted investment goals work together—meaning they recognized that a new small business initiative or food co-op, on its own, wouldn’t move the needle on neighborhood outcomes, but when they aligned and layered multiple investments across these areas in tandem, they could significantly transform neighborhood well-being.

Five key wins from local markets implementing community-centered economic inclusion

Through qualitative interviews and an analysis of local investment data, five key outcomes emerged from the implementation of these CCEI investments. The CCEI model:

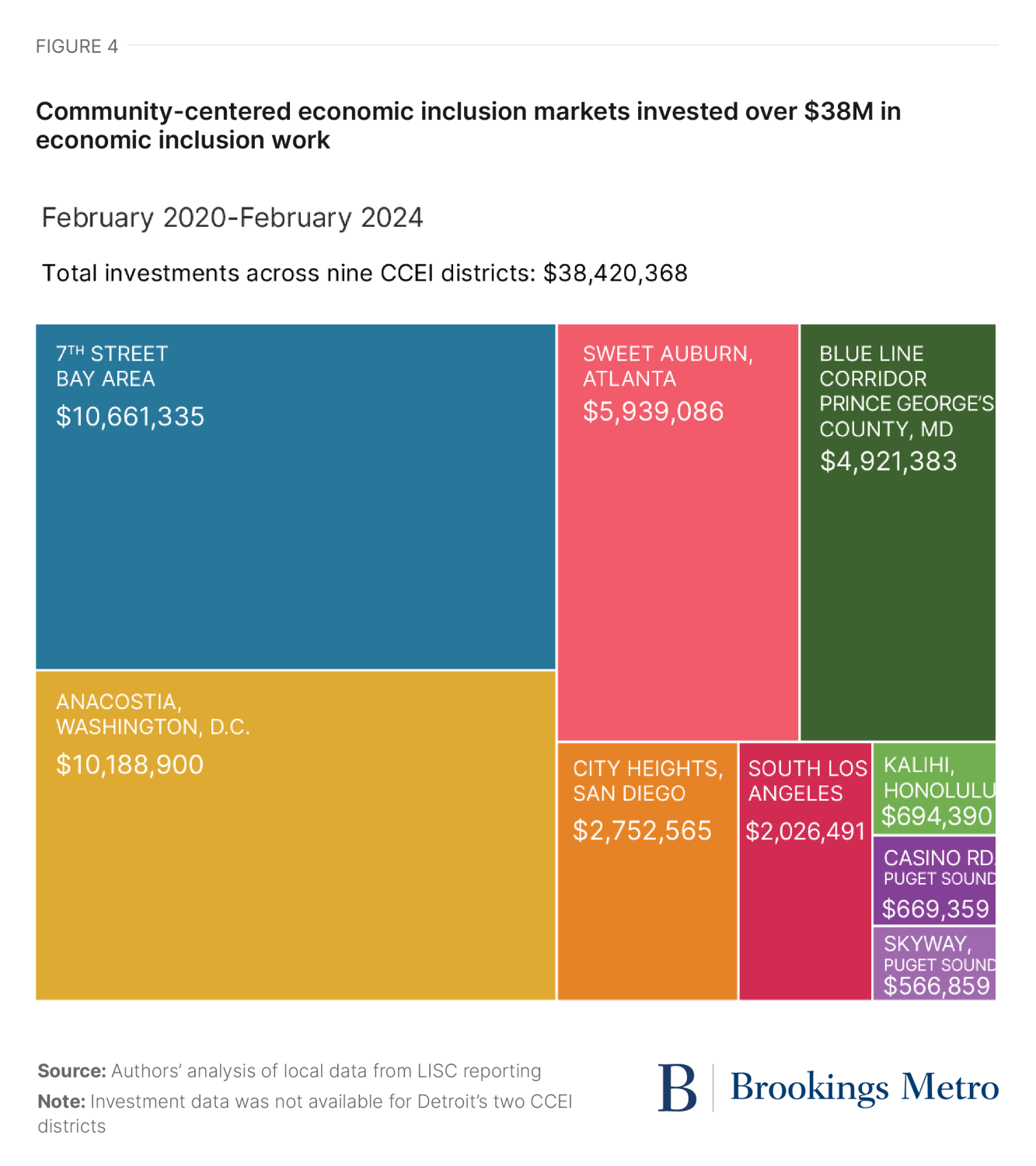

- Significantly increased public, private, and philanthropic investment in underinvested neighborhoods. (Figure 4; for more information, see pages 42-45 in the report.)

- Fostered greater capital access, capacity-building, and market opportunities for neighborhood small businesses owned by people of color, women, and legacy residents. (For more information, see pages 46-51 in the report.)

I take it as a very large victory that the majority of applicants had never received capital before. We were successful in reaching the most marginalized business owners. It was not easy—there’s a lot of mistrust. We had to do on-the-ground canvassing and work with partners to gain that trust. With the applicants that we received, they’re now more engaged some of our other programs.

A South Los Angeles stakeholder

- Facilitated a range of physical improvements in underinvested neighborhoods, including the reuse and redevelopment of vacant real estate, development of affordable housing, and creative placemaking. (For more information, see pages 52-57 in the report.)

- Encouraged new approaches to improve public health and wellness in underinvested neighborhoods, including through food entrepreneurship, community safety investments, and built design. (For more information, see pages 58-61 in the report.)

The 395 overpass is a classic example of a highway that separates communities . . . It’s not a safe area to walk. And when you go further up in the district, it’s been a hotspot for violence. A huge driver of this is disinvestment . . . We have a long-term opportunity to weave in safety and space design through a health lens into that district.

An Anacostia, Washington, D.C. stakeholder

Malama ʻāina (meaning “caring for and honoring the land”) in the garden at Hoʻoulu ʻĀina as community work together to grow food for Kalihi kūpuna (elders). Through engaging in indigenous Hawaiian food cultivation practices, Kalihi residents are reminded of the link between the well-being of the land and the well-being of the community. | Photo credit: Kaʻōhua Lucas

Staff at the Roots Café and Market – a food hub that supports small and micro-producers to sell their healthy food products from the KKV Wellness Center to provide healthy options like free-range eggs, fresh poi, local fish, breadfruit, kalo, cassava, banana, and leafy greens to the Kalihi community | Photo credit: Kaʻōhua Lucas

- Enhanced the capacity of community-based entities and facilitated new and improved relationships between neighborhoods and the public and private sector, while catalyzing early city policy wins. (For more information, see pages 62-70 in the report.)

Recommendations for practitioners, public officials, and philanthropies to support and scale community-centered neighborhood revitalization efforts

Several critical lessons that can help other cities and regions achieve their short- and long-term economic inclusion goals emerged from this evaluation (for more information, see pages 72-80 in the report). Embedded throughout the report, these include recommendations on how public sector officials can more effectively and equitably prioritize “place” in regional economic development, how philanthropic stakeholders can better support the local capacity needed for community-centered efforts to be successful, and how local community and economic development stakeholders can support the governance and accountability structures needed for long-term sustainability.

While the full impact of CCEI is far from realized, its results so far reveal its promise as a tested model to more equitably allocate resources, craft policy about place, and share power between community, city, and regional stakeholders. To be successful over the long term, CCEI requires taking a hard look at the experience of its implementors, funders, and beneficiaries and embedding their insights into the future of place-based, community-led revitalization policy.

Mural in Anacostia, Washington, D.C. | Photo credit: Authors

Local artist Sydney James’ mural, “Girl With the D Earring”, painted prominently on the Chroma building in Milwaukee Junction, Detroit, celebrates Black women in Detroit’s past and future. | Photo credit: Authors

Artwork in a neighborhood park in City Heights, San Diego | Photo credit: Jana River Medlock Photography

Public art in Oakland, Calif. | Photo credit: Authors

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Graphic design by Cecily Anderson, anagramist.com.