According to our latest poll, two-thirds of Americans, including majorities of Republicans, Democrats, and independents, favor making defending human rights a goal of American foreign policy—and a plurality feel the best way to do so is through working with international organizations. Yet Americans are ambivalent about the goal of spreading democracy globally.

These are some of the key findings of our University of Maryland Critical Issues Poll with Ipsos, fielded January 29-February 5, 2024, among 1,891 respondents from their probability-based panel, with a margin of error of 2.4%.

The findings are potentially consequential for shifting public perceptions of President Joe Biden and his administration.

Three takeaways

First, Americans strongly support defending human rights globally. When asked whether defending human rights globally should be a goal of American foreign policy, 65% of respondents said yes, including 60% of Republicans and 78% of Democrats. In addition, 65% of both young respondents and respondents ages 35 years and older said defending human rights globally should be a goal.

Second, Americans say that the best way to defend human rights is by working with international organizations. Among respondents who said human rights should be a foreign policy goal, a plurality (38%) said the best way was by working through international organizations such as the United Nations, including a plurality of Republicans (29%) and nearly half of Democrats (48%). Just under one-quarter of respondents said the best way for the United States to defend human rights is by setting a good example, including 22% of Republicans and 23% of Democrats. Thirteen percent of respondents, including 19% of Republicans and 9% of Democrats, said the United States should use economic boycotts if necessary and 10% said the United States should use incentives such as foreign aid, including 10% of Republicans and 12% of Democrats.

It turns out that Americans want to work with international organizations, at least when the issue is human rights.

Third, Americans are ambivalent about advocating for the spread of democracy globally.

Respondents were split on whether spreading democracy globally should be a goal of American foreign policy, with 34% of respondents saying “yes” and 33% saying “no,” and 33% saying they don’t know. Democrats were a little more supportive (43%) compared to Republicans (39%).

Among those wanting the United States to pursue spreading democracy in its foreign policy, a majority of Americans (52%), including 49% of Democrats and 54% of Republicans, said that the best way to help achieve that goal is for the United States to serve as a good model, followed by “working through international organizations, such as the United Nations” (28%).

There are likely three reasons for this ambivalence. The first may be lingering memories of the failed military campaigns in Iraq and, to a lesser extent, Afghanistan, carried out at least partly in the name of spreading democracy.

The second is that while Americans think that the best way to advocate for democracy globally is to be a good model, only 25% of Americans think that democracy in the United States is now a good model for the rest of the world to follow, with 54% saying “it used to be a good example but has not been in recent years.”

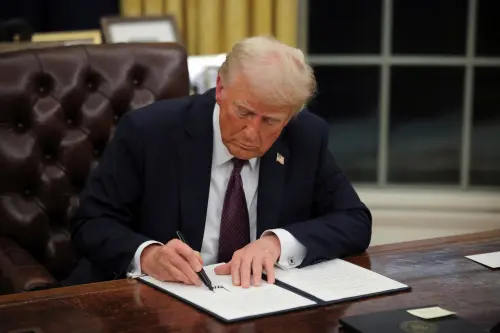

The third reason may be Americans’ assessment of the likely Republican and Democratic candidates for U.S. president in 2024: A majority (59%) said the presumptive Republican candidate, Donald Trump, is a threat to democracy, while nearly half (49%) said the Democratic candidate for president, Joe Biden, is a threat to democracy.

Conclusions

While it is difficult to measure the extent to which the Biden administration’s backtracking on human rights has impacted the president’s popularity or how it may impact his electoral prospects in 2024, the poll shows a large majority of Americans care more about human rights than is often assumed. This may be consequential for Biden, who had highlighted his commitment to human rights in his 2020 presidential campaign and during his first few months in office, but later faced at least one official resignation in the Department of State over a perceived lack of commitment to this issue.

There has also been much evidence in polls over the past seven months that many Americans, especially Democrats, have been at odds with Biden’s policies that touch on human rights, particularly in the Middle East, such as civilian casualties in Gaza, violations of international humanitarian law, and the need for a cease-fire. Our own polls in October and November showed how Americans initially rallied behind Israel after they learned of the large civilian casualties in Hamas’s attack, before they started swinging, especially young people, toward sympathy for Palestinians.

Human rights organizations that may have been encouraged by the Biden administration’s early statements on human rights have turned into critics on its Middle East policy. Recent polls have shown that a large majority of Americans want a cease-fire in the Gaza war, and that a majority of Democrats believe that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. Some protesters have labeled the president, “Genocide Joe.”

Humanitarian issues appear to be impacting broader perceptions of Biden’s stance on human rights, not only among young people, but also among other segments of the public. Last November, for example, 900 Black Christian leaders bought a full-page ad in the New York Times calling for a Gaza cease-fire and slamming Biden’s stance. “People want strong, moral, principled leaders, and they’re looking for that in President Biden … we didn’t get that,’ said one.

Americans seem to also differentiate advocacy for human rights from advocacy for democracy globally, strongly backing the former even as Biden’s policies effectively deemphasized it, and resisting the latter, even as Biden attempted to use it to link his policies toward Israel and Ukraine.

It is also notable that Americans want the United States to work with international organizations, such as the United Nations—at least when it comes to the objectives of defending human rights.

This may surprise those who are critical of international organizations, but it shouldn’t: A 2023 Pew poll showed that 58% of Americans held favorable views of the United Nations, a slight decrease from the year before. In contrast, Biden’s recent approval ratings have been around 38%.

Finally, the gap between Democrats and Republicans on the advocacy for human rights and democracy and on the desirability of working with international organizations on these issues is much narrower than many issues facing the United States during a time of deep polarization. While 78% of Democrats wanted to make defending human rights a goal of American foreign policy, 60% of Republicans said the same; while a plurality of Democrats who wanted to advance human rights wanted to work with international organizations (48%), a smaller plurality (29%) of Republicans wanted the same. And while 43% of Democrats support the goal of spreading democracy globally, 39% of Republicans support the same.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Americans strongly support defending human rights globally

May 16, 2024