On April 25, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) will—for the seventh time in 20 years—address the issue of net neutrality. The lobbying—including a barrage of commercials by the cable association and Chamber of Commerce—has thus far rehashed the same old arguments that an open internet threatens the companies’ incentive to invest in broadband networks.

At the heart of net neutrality is whether internet service providers (ISPs)—cable companies such as Comcast and Charter and telephone companies such as AT&T and Verizon – should have the responsibilities of a common carrier that for decades have applied to telephone service. Such responsibilities—often described by reference to Tile II of the Communications Act—include behaving in a “just and reasonable” manner, including providing non-discriminatory access to their networks.

Over the decades of its existence, the discussion of net neutrality has evolved as online services evolved. Its earliest iteration involved Comcast blocking the streaming of video programming. As websites were introduced, the issue also became ISPs’ control of access to these new sources of information. Now, two decades after the debate began, artificial intelligence (AI) has once again amplified the importance of non-discriminatory access as well as just and reasonable behavior on the last mile of the internet that connects consumers and businesses.

To address the role of net neutrality in the age of AI, I went to the oracle itself to ask, “How does AI change the importance of net neutrality?” ChatGPT 4 responded, “As AI continues to evolve and become more integral to our daily lives, maintaining an open and equal internet becomes even more crucial. Net neutrality not only supports the equitable development and deployment of AI but also ensures that the benefits of AI technologies are accessible to all, promoting innovation, fairness, and competition in the digital age.”1

According to ChatGPT 4, here are the specific benefits net neutrality brings to the implementation and development of AI:

- Increased Data Demand: “Without net neutrality, ISPs could throttle or prioritize traffic, affecting access to AI services and resources. This could hinder AI research and development, especially for smaller entities without the means to pay for better access.”

- Bias and Fairness: “With AI startups and innovations emerging rapidly, the absence of net neutrality could stifle competition by allowing established companies or those with agreements with ISPs to dominate, potentially slowing down the rate of innovation in AI.”

- Access to Services: “Many AI-powered applications and services require constant internet connectivity to function optimally. Without net neutrality, ISPs could control access to these services, impacting everything from AI-driven healthcare diagnostics to personalized learning platforms.”

- Global Accessibility: “The development of AI is a global effort, requiring collaboration across borders. Net Neutrality facilitates this by ensuring that data can flow freely and without discrimination. This is crucial for sharing AI research, accessing computational resources, and deploying solutions worldwide.”

- Ethical Implications: “The ability to control what can be accessed or prioritized by ISPs could lead to ethical dilemmas, especially if certain AI-driven content is censored or throttled. This raises concerns about who controls access to AI technologies and for what purposes.”

Thus, in the broadest sense, the basic principles of net neutrality—open and fair access to the most important network of the 21st century—are not changed by AI, but simply reinforced by its arrival. The GPT oracle’s observations—like all AI conclusions—must be vetted against human understanding, however. In this regard, these conclusions differ little from previous decisions about the importance of net neutrality to the distribution of video and online apps. It is also worth noting that, as was true earlier when the economic might of the dominant digital companies dwarfed that of the ISPs, the economic heft of the major AI providers (themselves often the same as the dominant digital platforms) outstrips that of the ISPs. Yet, it remains axiomatic that just and reasonable access to the network that enables online video, apps—and now AI—is foundational to the digital era.

As western civilization began to emerge from the Dark Ages in which feudalism bound the people to their lord and his self-serving rules, there developed new rules protecting the people from the powerful. This was English common law, so named because it was common to all courts. One of the foundations of common law was the “duty to deal.”

During the feudal period, an individual seeking to move his crop to market, for instance, could be discriminated against by the ferry operator on instructions from the local lord seeking to preference his own product. Similarly, lodging and food could be denied to travelers along the local highway. Under common law that changed. The duty to deal required that essential services could not discriminate among those seeking to use their offering.

The concept of non-discrimination in telecommunications service was enshrined in American law when, in 1860, President James Buchanan signed the Pacific Telegraph Act. That statute applied a duty to deal requirement to the new network technology. Not only did the law fund the transcontinental telegraph, but it also mandated that the messages on that network be “impartially transmitted in order of their reception.”

As network technology evolved from the telegraph to wired and wireless voice service, the same non-discrimination concept was applied. The term used for such non-discrimination was “common carrier.” The very existence of the internet is a consequence of such common carrier requirements. In its early days, the first iteration of the internet—known as dial-up—was carried by telephone lines. The FCC continued to regulate those lines as common carriers and thus required the telephone companies to provide non-discriminatory access to the new technology.

The phone companies didn’t like not being able to charge internet users. Echoing the complaints of the ISPs today, in 2005 the CEO of Southwestern Bell (today AT&T) teed up the net neutrality issue: “Now what they would like to do is use my pipes free,” Ed Whitacre told Business Week, “but I ain’t going to let them do that because we have spent this capital and we have to get a return on it.” Of course, there is no “using for free” for either the telephone network or last mile internet delivery as subscriber bills generate the necessary return on capital. Had early internet users been forced to pay an additional fee on top of the basic fee for a telephone connection, or to have its development controlled by the owners of those “pipes,” the internet would have been stillborn.

The idea that essential networks should provide just and reasonable non-discriminatory access has been at the heart of innovation, investment, and development for literally hundreds of years. That internet traffic is a different form factor from earlier common carriers—the transmission of zeroes and ones instead of the analog waveforms of a telephone call or the physical loads on a ferry—does not change the concept of just and reasonable non-discrimination that has been foundational to the free flow of commerce for centuries.

In 2004, Republican FCC Chairman Michael Powell, seeing the growing impact of the internet, proposed “Guiding Principles for the Industry.” Echoing FDR’s Four Freedoms, he proposed “Four Internet Freedoms”—(1) Freedom to Access Content, (2) Freedom to Use Applications, (3) Freedom to Attach Personal Devices, and (4) Freedom to Obtain Service Plan Information. In 2005, these principles became a voluntary policy encouraged by the FCC.

The next Chairman, Kevin Martin—also a Republican—put these principles into practice. In 2008, the FCC found Comcast was throttling the video streaming service BitTorrent, presumably because it was competitive with their core cable TV business. The FCC ordered Comcast to cease and desist the practice. Comcast appealed the decision to the courts on the grounds that the FCC lacked such authority since cable systems (unlike phone companies) were not common carriers. In 2010, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that the FCC lacked statutory authority over cable companies’ internet content delivery decisions.

In the years that followed, the FCC was forced to deal with the legacy of old law and FCC decisions that treated seemingly similar services differently based on whether they were provided by telephone or cable TV companies. Telephone companies were regulated as a “telecommunications service” and thus common carriers, while cable company internet access was an “information service” not subject to the same rules. This dichotomy was rooted in a 2005 Supreme Court decision—the Brand X case—upholding a 2002 FCC decision that cable was an information service. Shortly thereafter, the FCC removed the dichotomy with a decision declaring telephone digital subscriber line (DSL) service as an information service free of common carrier regulation.

It fell to the next Chairman of the FCC, Obama-appointee Julius Genachowski, to grapple with the matter of ISP behavior. Whereas the original debate about internet openness revolved around video services, in the intervening years the World Wide Web had redefined the nature of the internet to also include websites and apps. Chairman Genachowski proposed amending the earlier guidelines to establish the concept of nondiscrimination as well as full disclosure to subscribers of the ISP’s access policies. In December 2010, the FCC, on a 3-2 party line split, adopted new rules on net neutrality. This so-called “light touch” plan did not declare ISPs to be common carriers but did impose common carrier-like obligations, including a prohibition on blocking or throttling lawful content. Verizon sued to overturn the 2010 decision.

In January 2014, the Court of Appeals ruled against the FCC’s “light-touch” decision, principally on the grounds that since the FCC had not determined ISPs to be common carriers, then common carrier-like regulation such as no blocking or throttling could not be imposed. By that time, I was Chairman of the FCC. In February 2015, the Commission, once again by a 3-2 vote, declared ISPs to be common carriers. That decision was upheld by the same court of appeals that had voided the earlier efforts.

In 2017, the Trump FCC, at the request of the ISPs, abolished the 2015 rules. On April 25, 2024, the FCC under Chair Jessica Rosenworcel will once again address the net neutrality issue with a proposal that for the most part tracks the 2015 decision.

The companies that control the internet’s last mile have, once again, taken up arms against net neutrality. One of their tactics this time is television commercials.

“U.S. Chamber Launches Seven-Figure Ad Buy to Combat a Pattern of Regulatory Overreach Jeopardizing Broadband Connectivity,” a February 2024 press release from the Chamber of Commerce trumpeted. The 12-week campaign’s 30-second commercial touts the billions of federal dollars being spent—largely as subsidies to ISPs—to expand internet access to unserved areas, but with an ominous warning. “Congress made historic investments to improve internet access across the country,” the ad proclaims. “But now we’re moving backward because activist regulators…are undermining our progress with overregulation that threatens critical investment in new internet infrastructure.”

The association of cable operators, NCTA—The Internet and Television Association—has a similar series of commercials. The ads embrace the Biden administration’s “Internet for All” initiative that will spend over $40 billion to subsidize companies such as NCTA members to build broadband in areas they have thus far failed to construct. “But the FCC wants to enact needless regulation that will hurt this historic opportunity,” the ad warns. It would seem illogical for the cable companies to turn their backs on billions of federal dollars to add new paying customers simply because of net neutrality, but that is the threat the ad delivers.

It is the “same old, same old” argument. Since the beginning of the net neutrality debate, the go-to complaint of the ISPs has been that regulation stifles their ability to invest in broadband expansion. Even when new government programs are providing that investment, the same old mantra is rolled out. The millions of dollars ISPs have spent on television commercials opposing net neutrality suggests it is indeed possible to bite the federal hand that feeds you.

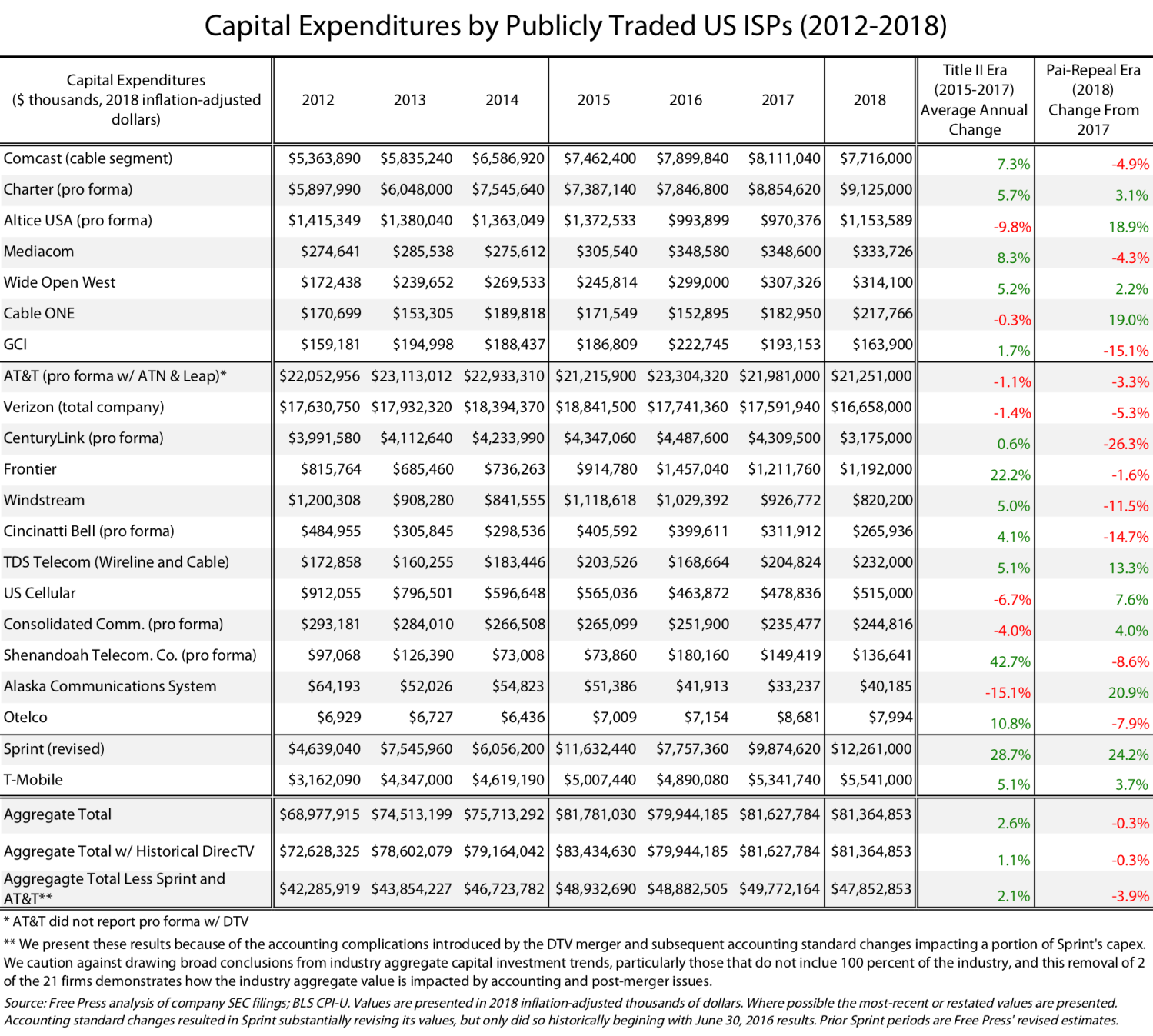

The companies are spending millions of dollars asserting a harm to broadband investment that has been disproven by their own actions. As the study below by the public interest group Free Press demonstrates, capital expenditures by publicly traded broadband providers increased during the years net neutrality was in effect and declined after the Trump FCC’s repeal.

This chart is an analysis of what the companies tell their shareholders under the supervision of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as opposed to their lobbying claims. While causal impact conclusions can be imprecise because of the multitude of decisions represented by an aggregation of capital expenditures, these numbers speak to the assertions that net neutrality rules discourage network investment.

Source: S. Derek Turner, “Raw Data Reveal Reality: Title II and Net Neutrality Edition,” March 17, 2019

Beyond this data, the executives of the ISPs in their SEC-overseen reports to shareholders confirm the lack of negative impact from net neutrality. Even while the 2015 rules were being considered (December 2014), the CFO of Verizon contradicted the company’s lobbyists, telling a Wall Street conference, “I mean to be real clear, I mean this does not influence the way we invest.” The CEO of Charter Communications told the FCC in December 2015, “The commission’s decision to reclassify broadband internet access under Title II has not altered Charter’s approach to investing significantly in its network.” The CFO of the nation’s largest cable company, Comcast, echoed that idea in December 2016, “the fear of what Title II could have meant, [was] more than what it actually meant.” These observations were confirmed by a 2024 study by Free Press that found that during the period in which Title II net neutrality’s return was a matter of active discussion, it was “not mentioned, or even hinted at, by a single ISP on any full-year 2023 investor calls or other investor conference appearances.”

Also telling is how the ISPs have behaved when California passed a state statute that paralleled the 2015 Obama FCC’s decision. After suing to block the California law—and losing—the companies have not only complied, but also have been unable to demonstrate that such compliance has had the threatened impact on revenues, profits, or construction.

The second most popular argument made by the ISPs against net neutrality (after the investment claim) is “But where are the abuses?” Ignoring the history of their practices that triggered the issue in the first place, the companies seek to rewrite history. “Internet service providers have always delivered open, unrestricted internet service,” the cable association states on its anti-net neutrality website. Recall, of course, how it was Comcast’s throttling of competitor BitTorrent that triggered the FCC’s first action in support of network nondiscrimination.

Beyond this history, it is worthwhile to listen to what Verizon told the court about its intended future behavior if its appeal of the 2010 FCC order was successful. The company’s lawyer told the court that if the FCC’s decision against discrimination was overturned, that it saw such discrimination as a viable option. In response to a question from one of the judges, the Verizon lawyer explained, “I’m authorized to state from my client today that but for these [FCC] rules we would be exploring those types of [discriminatory] arrangements.”

“Broadband providers have been quietly taking advantage of an internet without net neutrality protections and where the FCC has no legal authority to police harmful conduct by broadband providers,” public interest group Public Knowledge concluded in a study the year after the Trump FCC repealed the open internet rules. Verizon, for instance, throttled a California fire department’s wireless service in the midst of fighting a huge wildfire during the period between the repeal and the California law.

Such throttling of services is commonplace. Researchers from Northeastern University and University of Massachusetts found in a 2019 study that wireless carriers slow down internet speed for selected video streaming services, not just for network management (which is permitted), but “all the time, 24/7, and it’s not based on networks being overloaded.” The year after the Trump FCC’s repeal of net neutrality, for instance, Sprint throttled traffic to Skype which competed with Sprint’s calling service. The ISPs have also reneged on their pledge during debates over the 2015 rules that they would not engage in paid prioritization to create “fast lanes” and “slow lanes” based on the user’s willingness to pay.

Thus far, the arguments put forth against net neutrality have been a regurgitation of the same old lobbying talking points. Those arguments, however, now face a new reality—another online innovation, access to which depends on a third-party ISP.

Make no mistake about it, the major AI platforms are not weak wallflowers compared to the ISPs. There is a pressing need for regulatory oversight of the Big Tech companies that have delivered Big AI, including basic concepts such as openness, privacy, and interconnection.

Yet, access to AI for purposes as diverse as medical research or writing a term paper would be compromised without a fair and open internet. The issue before the FCC on April 25 is bigger than the catchphrase “net neutrality.” The 2024 iteration of the open internet debate is the reiteration of an issue that first surfaced in 2004: whether the dominant and essential network of the 21st century will go unsupervised.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

T-Mobile, Charter Communications, and Verizon are general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the author and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- March 16, 2024, 9:22 AM, ChatGPT-4: “Net neutrality has traditionally been defined in terms of video and web sites; how does AI change the importance of net neutrality?”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

AI makes the fight for net neutrality even more important

April 9, 2024