The paper summarized here is part of the spring 2021 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. Research findings are presented in a clear and accessible style to maximize their impact on economic understanding and policymaking. The editors are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Northwestern University Professor of Economics Janice Eberly and Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Harvard University Professor of Economics James Stock. See the spring 2021 BPEA event page to watch paper presentations and read summaries of all the papers from this edition.

Middle schoolers in U.S. counties where fewer adults have advanced cognitive skills seem less likely to develop advanced skills themselves, according to a paper presented at a Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference on March 25.

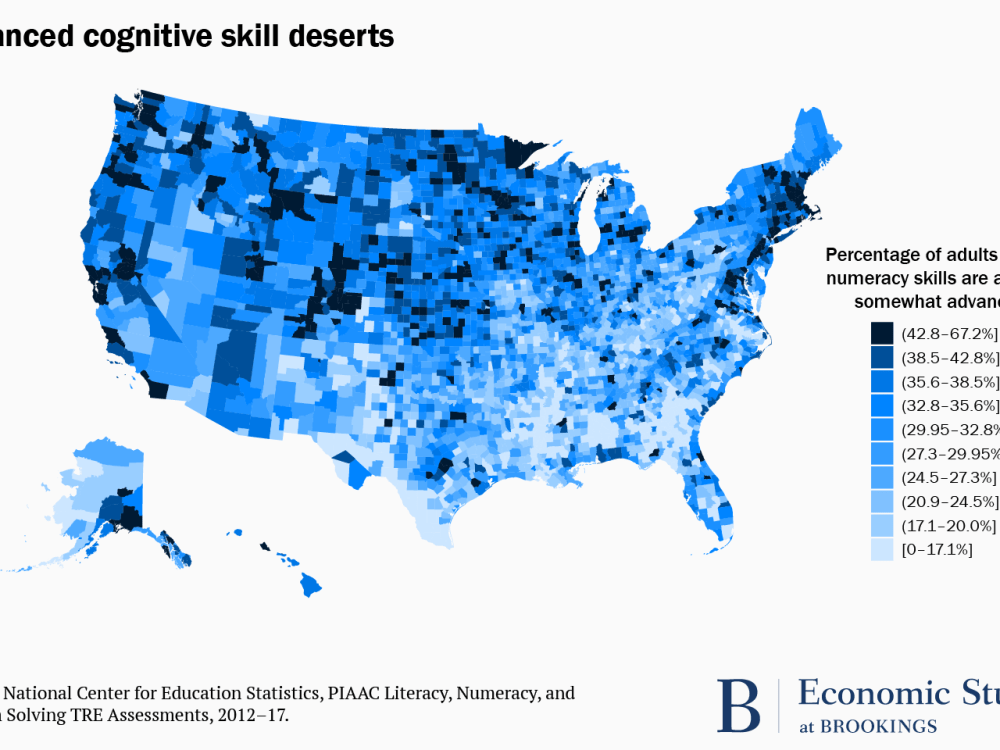

In Advanced cognitive skill deserts in the United States.: Their likely causes and implications, Caroline M. Hoxby of Stanford University maps county-level data from standardized tests to show which regions have higher percentages of adults and children with advanced skills and which areas have lower percentages. She compares data for adults, 12th graders, 8th graders, 5th graders, and 3rd graders and finds that regional patterns, evident among adults, only begin to emerge by 8th grade and are similar to adults by 12th grade.

This suggests, according to Hoxby, that early adolescence (from the ages of 10-11 to 14-15 for girls and from 11-12 to 15-16 for boys) is an “age of opportunity” for developing higher-order reasoning: a capacity to solve problems through logic, think in the abstract, engage in critical thinking, and derive general principles from a set of facts. According to neuroscientists, at those ages the frontal lobe of the brain, responsible for higher reasoning, is undergoing intense development.

Thus, improving the early adolescent experience may be crucial to equipping people with the cognitive skills necessary for success in a job market that increasingly demands them, she said in an interview with Brookings. “If you are going to make an intervention to improve advanced cognitive skills, you need to hit early adolescence because that is when the brain is most responsive.”

Hoxby’s data map for adults shows advanced cognitive skills are generally, but not always, most prevalent in counties with colleges, high-tech companies, and other employers requiring advanced skills. These include the areas around Boston, New York City, and Washington, D.C.; coastal Washington state and Oregon; the Salt Lake City area; and, in California, San Francisco, Sacramento, Los Angeles, and San Diego. But they are also prevalent in the so-called “Lutheran Belt” (southern Minnesota and parts of Wisconsin, Iowa, and the Dakotas).

The map shows “advanced cognitive skills deserts” including one that runs through Appalachia (northeastern Mississippi, northern Alabama, northern Georgia, eastern Tennessee, eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, southeastern Ohio, Pennsylvania, and parts of the Carolinas, Virginia, Maryland, and New York), another in the Ozarks, and yet another that runs through inland areas of the South (parts of Louisiana and Mississippi, north Florida, northeastern Georgia, and parts of South Carolina and North Carolina). Even in these “deserts,” counties with colleges and universities have high percentages of people with advanced cognitive skills.

Hoxby concludes that evidence suggests that the scarcity of adults with advanced cognitive skills affects adolescents more than younger children. Middle schools in “deserts” may lack funding or find it hard to recruit skilled teachers. Low population density in some areas may prevent schools from being large enough to offer specialized classes.

But it may just come down to a relative neglect of early adolescents, she told Brookings. “Schools and communities do not always feel a sense of urgency about them, compared with younger or older children.”

In any case, she views the “deserts” as opportunities. “I believe that the vast majority of children can acquire advanced cognitive skills, as I define them. Deserts bloom when they get water. How do we know what can be attained unless we attend to the period at which the brain is most receptive?” she asked.

The paper also provides speculative evidence on possible links between advanced cognitive skills, economic fatalism, social trust, and politics. Students who reach the end of high school without acquiring advanced cognitive skills may see little hope for achieving economic security, Hoxby writes. They may resent and distrust intellectual “elites” with better prospects and support politicians who oppose trade and immigration.

acknowledgments

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper. Becca Portman assisted with data visualization.

Citations

Hoxby, Caroline M. 2021. “Advanced Cognitive Skill Deserts in the United States: Their Likely Causes and Implications.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 317-351.

Hurst, Erik. 2021. “Comment on ‘Advanced Cognitive Skill Deserts in the United States: Their Likely Causes and Implications’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 352-356.

Jacob, Brian A. 2021. “Comment on ‘Advanced Cognitive Skill Deserts in the United States: Their Likely Causes and Implications’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 356-363.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The author did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are not currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this paper.

Disclaimer

The views expressed by the authors, discussants and conference participants in BPEA are strictly those of the authors, discussants and conference participants, and not of the Brookings Institution. As an independent think tank, the Brookings Institution does not take institutional positions on any issue. Please contact Haowen Chen ([email protected]) if you have any questions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).