Editor’s Note: The following is a Campaign 2012 policy brief by Ron Haskins proposing ideas for the next president on reducing the federal budget deficit. Isabel Sawhill prepared a response arguing that while deficit reduction is crucial, near-term economic stimulus is a better prescription for curing the nation’s economic ills. William Gale also prepared a response arguing that tax reform should make the nation’s tax system more equitable and progressive.

Introduction

The two biggest issues in the 2012 election are the economy and the deficit. Opinions vary on which issue should take priority, but the polls show that Americans put both issues at the top of those they want their new president to address. Not surprisingly, all the Republican candidates and President Obama have promised that they will reduce the nation’s deficit in the near future. Although none of the Republican candidates have laid out a detailed plan for deficit reduction, all of them would cut spending deeply and none would increase taxes. President Obama, by contrast, has consistently called for both spending cuts and tax increases, especially tax increases on the rich. All of the Republicans have also called for reducing the growth rate of entitlement programs, including Medicare and Social Security, although, again, they do not offer specific plans for doing so. However, they all call for a basic reform of Medicare financing—usually called “premium support”—in which the elderly would be given a fixed amount of money each year to purchase a health insurance plan of their choice. By contrast, President Obama, as recently as last December, has specifically ruled out this type of Medicare reform. Thus, Americans will be offered a clear choice between President Obama and any of the Republican candidates on deficit reduction: President Obama would cut spending other than Medicare and Social Security, the two biggest entitlements, and increase taxes on the rich; Republicans would cut spending, including spending on the big entitlements, while not increasing taxes.

This paper will show that the deficit is placing the nation at great risk of a financial disaster, argue that both political parties have failed to offer politically feasible plans to reduce the deficit and explain why, and outline a plan by which the new president can get the deficit under control. The next president should act decisively to solve the deficit crisis by taking the following steps:

- Opening negotiations with the congressional bipartisan leadership in which everything—entitlements and taxes alike—is on the table;

- Pushing reforms on Medicare based both on some of the top-down funding control mechanisms in the Democrats’ Affordable Care Act and the type of Medicare spending control measures specified in the Ryan-Wyden and Rivlin-Domenici proposals; and

- Achieving reforms of the budget process, including—most important—resurrection of the paygo rule.

Background

The nation’s most serious domestic problem is the exploding federal deficit. The deficit has been over $1 trillion for the last three years and is expected by some estimates to be over $1 trillion on a permanent basis. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that under current policy the deficit will be $3 trillion by 2030 and $9 trillion by 2050. With around 10,000 Baby Boomers retiring every day for the next three decades, and nearly all of them qualifying for Social Security and Medicare, unless the federal government undergoes a profound shift in its spending and tax policy, we will soon be Greece.

With the financial future of the nation at risk, you would think federal policymakers would take strong action to prevent the apocalypse. In a rational world, events that are certain to occur but at an uncertain time nonetheless receive timely attention and action. Even so, officials in Washington, and apparently the American people, are willing to let time pass by despite the guillotine featuring a frayed rope poised over our collective necks.

An especially distressing aspect of the paralysis in Washington is that everyone knows the broad outlines of the solution. Reducing the deficit can be achieved by cutting spending as Republicans want to do, increasing taxes as Democrats want to do, or both. It is in the very nature of democratic government that major reforms involve compromise between the contending forces. Yet Republicans and Democrats have been unable to reach a compromise involving less spending and higher taxes. If President Reagan and Ways and Means Democratic Chairman Dan Rostenkowski were still alive, they could go into a room and within an hour work out the general features of a compromise that would restore the nation’s fiscal health over a decade—and give us a more equitable and efficient tax code in the bargain.

The major reason the contending parties have been unable to make reasonable progress is that the policies that must be enacted to reduce the deficit lie at the heart of each party’s agenda. The Republican Party considers itself the philosopher of small government and its companion low taxes. Since the dramatic rise of federal social programs during the Great Depression, and even more since the flood of programs that accompanied the twin hurricanes known as the Great Society and the War on Poverty authored by Lyndon Johnson, Republicans have been on the defensive in their goal of achieving limited government. With the federal government’s annual volume summarizing domestic assistance programs now running to 2,839 pages and with spending on means-tested programs having risen from around $50 billion in the mid-1960s to around $700 billion today (in constant dollars), Republicans have long believed they are losing the battle for limited government. The record of federal spending shows why the Republican perception that they are losing the war for small government is accurate. From the 1950s through the 2000s, here are the decade-by-decade annual averages for federal spending as a percent of GDP: 17.6, 18.6, 20.0, 22.2, 20.7 and 20.0. CBO projects that spending in the 2010s will average nearly 24 percent of GDP. In 2011, one percent of GDP was about $150 billion.

In their frustration over the relentless growth of spending, around the time of the Reagan Presidency Republicans dreamed up the strategy of “starving the beast.” If they couldn’t stop either the Democrats (or, to be honest, themselves) from creating new programs and spending more money, they decided a radical strategy was called for; namely, depriving the government of money so it couldn’t continue to grow. Hence the importance of “no new taxes” to the Republican agenda. Based on the spending history of the federal government outlined above, starve the beast has backfired and both federal spending and the deficit have continued to grow to a previously unthinkable level. The United States now has a total debt of over $15 trillion, more than a quarter of it borrowed over the last four years. So much for starving the beast. Indeed, it seems possible that starve the beast taught both politicians and the public that they could have copious benefits—not to mention fight two wars—without paying for them. One consequence of our huge debt is that despite historically low interest rates, in 2010 the federal bill for interest on the debt was $196 billion. By the mid-2020s, we will be paying $1 trillion every year in interest and interest payments will continue to grow forever as we add new debt.

Republicans have had many chances to reduce federal spending, but rather than reduce spending, as often as not, they have increased it. The prime example is the prescription drug benefit Republicans added to Medicare early in the Bush administration. Not only does that program now cost the federal government over $50 billion a year, a figure that keeps rising, but it also makes the goal of controlling Medicare spending even harder to achieve. Similarly, the nation initiated two wars under Republican leadership, and neither of them was paid for. To date, expenditures on the two wars have been in excess of $3 trillion, although some estimates are even higher.

If Republicans have done their share to turn the United States into a financial banana republic, Democrats are no better. The heart of the Democratic agenda is protecting Social Security and Medicare, the two entitlement programs that Democrats rightly consider to be their greatest contribution to the American people, although both were originally enacted with and continue to enjoy strong bipartisan support. Even so, over the years Republicans have been more willing than Democrats to reform entitlements, especially Medicare. Taking a huge political gamble, the House Republican budget for 2012, developed primarily by Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, contained a provision that would substantially reduce spending on Medicare and change its basic funding mechanism in a way that would control Medicare spending in the future. But many Democrats have excoriated Republicans for their Medicare proposal and are planning to claim that Republicans would throw Grandma in a pit to avoid higher taxes. Nancy Pelosi, the leader of House Democrats, said publicly that there could be no reductions in spending on either Social Security or Medicare and that Republicans are trying to let Medicare “wither on the vine.”

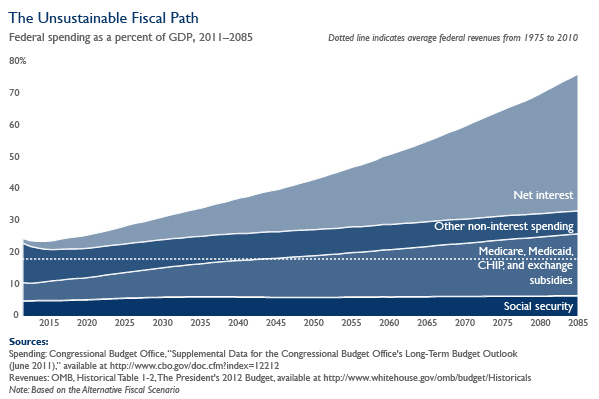

The upshot of the Republicans’ insistence on low taxes and the Democrats’ protection of Social Security and Medicare can be seen in Figure 1. If we continue on our present course, federal spending, which has averaged a little over 21 percent of GDP for the past several decades, will reach 30 percent of GDP by the late 2020s, 40 percent by the late 2040s, and 70 percent by the late 2080s. By contrast, federal revenues have averaged around 18 percent of GDP for the past several decades, although under reasonable assumptions future revenues could easily be under 18 percent and will almost certainly be under 19 percent of GDP. You can’t sustain a government on revenues equal to 18 or 19 percent of GDP while spending rises to 30 percent, 40 percent, and eventually 70 percent of GDP. To paraphrase the late economist Herb Stein, any trend that can’t continue, won’t.

So the big question for all the presidential candidates, and indeed all elected federal officials, is when they plan to rescue the nation from the debt tsunami and whether the rescue will occur before or after we have a catastrophic financial crisis that will bankrupt the nation.

The Obama and Republican Records

Not to be underdone by either his own party or the Republican Party, President Obama has done little to reduce the nation’s deficit and a lot to increase spending. A good argument can be made that the $790 billion passed in 2009 to stimulate the economy was justified. But most of the stimulus spending ended after 2010. Nonetheless, the deficit in 2011 was nearly as great as the deficit in 2010 and the deficit in 2012 will still exceed a trillion dollars. Granted, the deficit was already a major problem when Obama assumed the Presidency. But he has neither stemmed the tide nor spelled out and fought for a plan to substantially reduce the deficit. Before Obama took office, the nation had never had a deficit that exceeded a trillion dollars except during and immediately following wars. Now, as his term ends, we have had several years of $1 trillion deficits and these huge deficits are certain to continue increasing in the future.

In the mid-2000s, when the deficit was around a fourth of its current size, analysts at Brookings played the role of Chicken Little with regard to the mounting federal debt by publishing a series of volumes (in 2004, 2005, and 2007) arguing that the deficit was an impending national disaster and proposing policies that would avert the disaster, including changes in health policy, which even back then was widely recognized as the single biggest cause of deficit growth. For the chapter that Isabel Sawhill and I wrote for the 2005 volume, I called 20 former members of Congress or senior staffers who had participated in major compromise deals reached in the past by Congress and the president. These included the 1983 Social Security reforms, the massive 1986 tax reform, and the 1990 and 1997 budget deals. I asked them about the factors they thought were crucial to achieving the compromise deals in which they had participated. Of the twenty people we interviewed, the factor cited by the most participants (16) was presidential leadership. No wonder. Any fair assessment of all four of these major compromise packages would conclude that Presidents Reagan, Bush the elder, and Clinton, who were in office during one or more of the big compromises, showed competent and even daring leadership in working on a bipartisan basis to reach agreement. It is widely believed that George H.W. Bush lost the presidency in the 1992 election because he violated his “no new taxes” pledge in order to take dramatic steps to reduce the deficit in the 1990 compromise. Presidential leadership was also remarkable in the 1983 deal, because reducing Social Security benefits and increasing taxes was deeply controversial and politically risky, and in the 1986 deal, because huge and well-financed opposition from powerful lobbyists protecting their clients’ turf had to be overcome.

President Obama’s failure to provide the kind of leadership shown by previous presidents from both parties cannot be excused because he lacked opportunities to fight for a compromise agreement. Each of the annual budgets proposed by President Obama was an occasion for laying out his vision of how to attack the deficit over the long term. In addition, there were at least two occasions in which the president had a clear opportunity to create a political dynamic that could have led to a deficit compromise. These were the publication of the Bowles-Simpson deficit commission report in December of 2010 and the debt ceiling fight in the summer of 2011.

Of these, perhaps the greatest lost opportunity related to the report of the Bowles-Simpson Commission. First, the president himself appointed the chairs of the Commission, which would ordinarily mean that the president would have some ownership of the final report. Second, under the silly Commission rules, which seem to have been designed to ensure failure, the final report and recommendations were not considered approved unless 14 of the Commission’s 18 members voted in favor of the report. The Commission may not have reached the magic number of 14 votes, but a majority of Commission members did support the final recommendations, which included a judicious mix of tax increases and spending cuts. Significantly, those signing the report included two conservative Republicans, Senators Tom Coburn and Mike Crapo. Thus, two prominent Republicans defied their party leaders and voted to support the substantial tax increases in the final report. Moreover, the report was greeted in the press with widespread acclaim as a huge step forward. Despite all these hopeful signs of a compromise, Obama treated the report like it was a barrel of snakes. If Obama had seized on the report, asked Senator Reid to introduce it (or a modified version) in the Senate, and thrown the full power of his office behind it, there is no doubt that a significant battle would have ensued and that Obama would have been occupying the high ground. What’s more, with two Republican Senators already in the fold and numerous cracks in the no-new-taxes armor, Obama could have split the Republican Party. Even if he hadn’t won the battle, perhaps in part due to divisions within his own party, he could well have emerged a hero in the media and among the public and all but assured his second term.

A second blown opportunity was the negotiation between the president and House Speaker John Boehner during the run-up to the debt ceiling vote in the summer of 2011. The negotiations turned into a “he-said, she-said” argument between the president and speaker when they blew up. According to both sides, the size of the package under discussion could have amounted to around $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years and included both tax increases and entitlement cuts. According to both sides, Boehner withdrew because the president wanted higher taxes than Republicans were willing to accept. Boehner, however, claimed that he had agreed to $800 billion in tax increases over 10 years, but the president moved the goal posts by asking for an additional $400 billion in taxes. The president denied Boehner’s version. Blame whom you will; the negotiations ended up as another blown opportunity.

The lack of presidential leadership was once again on full display in December 2011 when Republican Paul Ryan and a leading Democrat, Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon, introduced a version of the premium support approach to fundamentally reforming the Medicare program. Ryan, as part of his far-reaching plan for solving the deficit crisis, had included a less generous version of premium support that was viewed by many Democrats as putting seniors at too much risk for increased out-of-pocket payments for their medical care. Nonetheless, if viewed as an opening bid in a negotiation over Medicare funding, the original Ryan Medicare proposal could be seen as having potential for bipartisan negotiations. Alice Rivlin of Brookings, a leading Democratic budget expert, agrees with the basic approach of the Ryan proposal, although she opposed his original version. However, the version Ryan and Wyden released in December seems nearly identical to the proposal supported by the influential Bipartisan Policy Center and written by Rivlin and former Republican head of the Senate Budget Committee Pete Domenici. Both the Washington Post and the New York Times have written editorials arguing that the premium support approach to controlling Medicare costs deserves consideration and careful scrutiny. In short, a series of developments in Washington opened an opportunity to consider a reform that CBO has scored as reducing the growth rate of Medicare spending.

But presented with this opportunity to reform the single greatest force underlying the federal deficit, how did the administration respond? The White House immediately issued a statement claiming that the Ryan/Wyden proposal would “undermine rather than strengthen Medicare” and rejecting the bipartisan proposal out of hand. The White House appeared to be in the lead of a bevy of senior Democrats who, according to an Associated Press headline, “blasted” the proposal. The Washington Post, hardly a bastion of conservative thought, criticized the administration for missing a chance to explore a promising proposal that at least deserved careful scrutiny.

What Should We Expect from the Next President

The nation cannot afford another four years of a Congress and a president that fail to attack the deficit and, at a minimum, beat the debt back to a stable percentage of GDP—preferably, around 60 percent as recommended by the National Academies. The course to fiscal sanity is straightforward: Congress and the next president must work together to reduce spending, especially on Medicare, and increase taxes. None of the presidential candidates and neither political party have supported a detailed plan that involves cuts in spending, especially in Medicare, and tax increases that would avoid the pending financial crisis.

Thus, on his first day in office, the new president should meet with the bipartisan congressional leadership and agree to open a negotiation that would put everything— including entitlements and taxes—on the table, involve a determined search for a bipartisan deal and include a revamping of budget process rules so that the terms of the eventual deal would be enforced.

It would be especially wise for the new president to lay down three additional principles to guide the negotiations. First, rather than mindless across-the-board cutting of programs, the spending cuts should emphasize using evidence to eliminate or reform programs that don’t work and, if sufficient savings can be achieved, invest in programs that have strong evidence of success. One of the reasons the nation has such high unemployment is that too many of our workers lack adequate skills to flourish in a global economy. The key to rectifying this situation, of course, is education. If we are to overcome our decades-long failure to create educational institutions that can help children from the bottom complete high school and enter a postsecondary institution that provides a skill certification, a two-year degree, or a four-year degree, we should begin by providing high-quality preschool for at least two years to children from families below 150 percent of the poverty level. There is ample evidence that high-quality preschool produces long-term payoffs. The Head Start reforms now being implemented by the Obama administration are a step in the right direction, but more funding is necessary to maintain quality and to ensure a program of two years for more disadvantaged children. The United States now lags many other nations in educational achievement, a development that threatens our economic superiority. To regain our leadership position, we must make smart investments in high-quality educational programs and continuously evaluate the programs to ensure they are producing the desired results.

Second, if the new president is a Republican, he should open negotiations on Medicare by agreeing to some of the top-down funding control mechanisms in the Democrats’ Affordable Care Act, especially the advisory board that has authority to submit reforms to Congress shown by research to save money. But in exchange, Democrats should agree to some version of premium support, such as the Ryan-Wyden and Rivlin-Domenici plans, as an additional way to control Medicare spending.

Third, to ensure that the final agreement sticks and that the nation avoids deficits of the kind that now threaten our future, the president’s proposal should include reform of the budget process. The most important budget reform would be to resurrect the paygo rule under which any increase in spending or reduction in taxes that exceeds the targets in the agreement must be paid for. The agreement should also include a trigger that would impose automatic spending cuts and tax increases if the agreed upon targets are not met.

America is on the edge of a cliff. That the Congress, the president, and the American people themselves have allowed the budget disaster to fester and grow is a testament to the basic human desire to have something for nothing and the failure of our federal policymaking apparatus to put a stop to the fiscal insanity. My favorite cartoon about the nation’s deficit shows a table of adults at a sumptuous dinner with a baby seated in a high chair at the end of the table. When the bill arrives, all the adults point toward the baby as the person who will pay for their dinner. The entire nation is now at the table pointing toward the baby. One way or another, the adults must pay for their own meal and they should elect the president that they think gives them the best chance of doing so.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).