The Biden administration has responded positively to Saudi Arabia’s interest in civil nuclear cooperation with the United States—both because such cooperation is a Saudi condition for the normalization of Saudi-Israeli relations, which the administration strongly supports, and because it believes a bilateral civil nuclear partnership can bring important benefits to both countries. However, such cooperation needs to be pursued in a way that can realize those benefits without increasing the risks of nuclear proliferation.

A civil nuclear deal between the United States and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) could serve ambitious Saudi nuclear energy and commercial goals and help revitalize the U.S. nuclear industry. It could authorize a wide range of cooperative activities, including a lead role for U.S. companies in building the first phase of Saudi nuclear reactors and a Saudi investment in a U.S.-based uranium enrichment operation, which could help reduce U.S. reliance on importing enriched uranium from Russia.

Given the lack of any near-term programmatic or commercial justification for a uranium enrichment program in Saudi Arabia, the nuclear agreement should not authorize the U.S. construction of an enrichment facility in the kingdom, which would be a departure from longstanding U.S. non-proliferation policy. But during a moratorium period of perhaps 10 years, the parties should conduct a continuing review of the enrichment issue and keep open the option of constructing an enrichment facility in Saudi Arabia at a future time.

Deferring the question of domestic enrichment would enable Saudi Arabia and the United States to embark on mutually beneficial nuclear cooperation without raising concerns about proliferation or closing the door to future Saudi fuel cycle choices.

Long-standing U.S. policy on transferring fuel cycle technologies

A bilateral U.S.-Saudi agreement on civil nuclear cooperation is one of the KSA’s declared conditions for its normalization with Israel—along with U.S. security guarantees and a pathway to statehood for the Palestinians. Saudi officials maintain that such cooperation should include the U.S. construction of a uranium enrichment facility in Saudi Arabia—a facility capable of producing low-enriched uranium to fuel civil nuclear reactors but, if not subject to effective controls, capable of producing highly enriched uranium for use in nuclear weapons.

The Saudis point out that a domestic enrichment capability would enable the KSA to take advantage of the uranium deposits on its territory to provide fuel for its planned nuclear reactor program as well as to profit from the sale of uranium products on the international market. But a domestic enrichment program may have more than commercial and nuclear energy value for the kingdom. Given statements by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and other senior Saudi officials that the KSA is determined to acquire nuclear weapons if Iran does, Saudi interest in enrichment is viewed internationally as related to that strategic goal.

For decades, a central component of U.S. non-proliferation policy has been opposition to the proliferation of uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing (known as “fuel cycle”) capabilities. In addition to refusing to transfer fuel cycle equipment and technology to other countries, the United States has actively worked to discourage other nuclear supplier states from selling those technologies and potential recipient states from importing them. In negotiations in recent years on agreements for civil nuclear cooperation with other countries, Washington has sought a binding commitment not to pursue fuel cycle capabilities (often referred to as the “gold standard”)—but obtained such a commitment only in the case of its agreement with the United Arab Emirates.

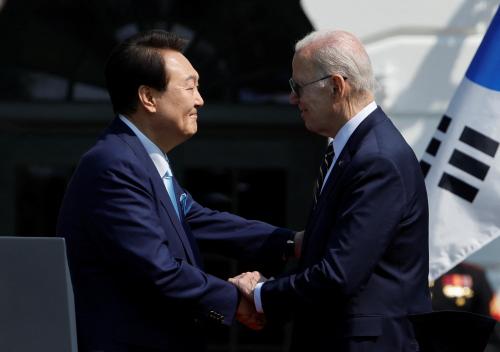

U.S. support for an enrichment facility in the kingdom could adversely affect the global non-proliferation regime even if adequate non-proliferation guardrails could be put in place to effectively preclude the possibility of contributing to a Saudi nuclear weapons capability. After saying “yes” to Saudi Arabia, how could the United States say “no” to a treaty ally like South Korea, which has tried without success to gain U.S. consent to enrichment on its territory? How could the United States dissuade Russia, China, or others from offering their customers an enrichment plant to sweeten their bids to sell nuclear reactors—and from making such an offer without insisting on the kinds of restrictions the United States would insist on to prevent diversion to a nuclear weapons program?

U.S. policy to prevent the proliferation of fuel cycle capabilities has been very successful. Since the demise about 20 years ago of the black-market network led by Pakistani scientist A.Q. Khan, which provided enrichment technology to Iran, North Korea, Libya, and perhaps others, there have been no known transfers of fuel cycle technologies to countries that do not possess them, either by state or non-state suppliers. It has been much longer since any state-sanctioned transfer of fuel cycle technology to a non-nuclear weapon state. Building an enrichment facility in the kingdom would be seen as a major reversal of U.S. nonproliferation policy.

During 2023, as part of its effort to address Saudi conditions for normalization with Israel, the Biden administration engaged in high-level, very closely held discussions with the KSA on civil nuclear cooperation. The two sides reportedly made significant headway in developing the broad outlines of a deal. But the Hamas attack on October 7 and the ensuing war in Gaza were widely assumed to put progress toward both normalization and a nuclear cooperation agreement on indefinite hold.

Apparently, that is not the case. Both Washington and Riyadh seem inclined to press forward, both on a civil nuclear deal as well as on the broader package that would facilitate normalization with Israel. Indeed, they appear to see urgency in reaching a broad agreement in the next few months before the U.S. elections complicate the process.

So, the Biden administration is now grappling with the challenge of responding positively to the Saudi demand for nuclear assistance—and thereby meeting a key Saudi requirement for normalization with Israel—while at the same time avoiding damage to U.S. non-proliferation interests.

Insisting on the “gold standard” would be a non-proliferation loss

Media reports regarding U.S.-Saudi nuclear negotiations have raised concerns in the United States, especially regarding the prospect of an enrichment facility in Saudi Arabia. In separate letters to President Joe Biden, a bipartisan group of non-proliferation and regional experts and a group of 20 Democratic senators both called on the administration to condition any U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear deal on a binding KSA commitment to forswear enrichment and reprocessing capabilities. In light of the declared Saudi intention to match any Iranian nuclear weapons capability, the two groups argued that failure to insist on the gold standard could lead to a Saudi nuclear weapons capability and a regional arms race.

From a non-proliferation perspective, it would clearly be best if Saudi Arabia accepted the gold standard and renounced fuel cycle capabilities. However, in negotiations on a bilateral civil nuclear agreement, both the Obama and Trump administrations pressed the Saudis for the gold standard but were firmly and repeatedly rebuffed. Most observers see no possibility of the Saudis reconsidering their position.

Insisting on a binding renunciation of fuel cycle capabilities would ensure that there would be no civil nuclear deal. The United States would forfeit any involvement in the KSA’s nuclear program, including the window it would provide into Saudi capabilities and plans and the opportunity to exert influence on aspects of the program related to non-proliferation, safeguards, safety, and security. The kingdom would turn to other nuclear supplier governments, including those that would be less demanding than the United States in terms of technology transfer restrictions, safeguards, and other non-proliferation controls. Instead of achieving a significant non-proliferation gain, pressing for the gold standard could result in a major non-proliferation loss.

Seeking a civil nuclear partnership with the KSA

Rather than excluding itself from any role in the Saudi nuclear program, the United States should pursue a broad public-private civil nuclear partnership with the KSA that could serve Saudi nuclear energy and commercial goals as well as help revitalize the U.S. nuclear industry and reduce American dependence on Russian enriched uranium—and could do so consistent with U.S. non-proliferation interests. Such a partnership would require Washington and Riyadh to negotiate a bilateral agreement for civil nuclear cooperation (called a “123 agreement” after Section 123 of the U.S. Atomic Energy Act), which would permit American and Saudi private and public entities to engage in a wide range of cooperative activities.

One such activity could be uranium conversion. The parties could agree that the United States would help the KSA build a uranium conversion facility in the kingdom, which would convert Saudi chemically processed uranium ore into the gaseous form of uranium (uranium hexafluoride, or UF6) used as the feed material for centrifuge enrichment. The Saudis could then sell their converted uranium on the international market, which is currently in short supply of UF6. Some could be shipped to the United States, where it could be enriched in a U.S.-based enrichment facility and used to fuel U.S. nuclear reactors, sent back to KSA to fuel future Saudi reactors, or sold to third countries.

A major component of the partnership could be U.S. support for the KSA’s ambitious plans for building nuclear reactors in the kingdom. Washington and Riyadh could agree that U.S. companies would play the leading role in the first phase of constructing Saudi nuclear reactors, including both large, conventional nuclear power reactors as well as small modular reactors (SMRs) which could be used for power generation, process heat, desalination, and other industrial purposes. American reactor vendors would provide the fuels for the reactors they build and perhaps could eventually train Saudi technicians to fabricate the fuels indigenously.

Another important element of the partnership could be Saudi acquisition of a stake in a U.S.-based enrichment operation. The Biden administration is determined to reduce and ultimately eliminate the United States’ reliance on Russian enriched uranium, which accounts for roughly a quarter of the enriched uranium used in the United States today. In December 2023, the House of Representatives passed legislation that would ban imports of enriched uranium from Russia by 2028. The Senate is expected to adopt the ban and Biden is expected to sign it into law. Yet current U.S. enrichment capacity is insufficient to replace imports from Russia; a significant expansion would be required.

To promote U.S. energy security, Congress has appropriated $2.72 billion to boost domestic enrichment capacity. While that level of government support will not suffice to finance a major new U.S. enrichment plant, it should give confidence to private U.S. investors to make up the difference. Still, foreign investors could play an important role. A Saudi investment in a U.S.-based enrichment company—which, depending on the terms of the arrangement, could entitle the KSA to receive an allocation of the enriched uranium product—could reduce the burden on U.S. public and private investors, help increase U.S. enrichment capacity, and reduce U.S. vulnerability to Russia. At the same time, it could provide Saudi Arabia with valuable experience in the enrichment business as well as furnish it with a reliable supply of enriched uranium that it could use to fuel its own reactors or market to third countries.

The question of domestic enrichment in the KSA

An issue sure to arise in U.S.-Saudi negotiations on civil nuclear cooperation is whether the nuclear deal, in addition to enabling the KSA to acquire a stake in a U.S.-based enrichment company, should authorize the near-term construction by the United States of an enrichment plant in the kingdom, which Saudi officials have reportedly called for.

When looked at from a programmatic or commercial perspective, the early pursuit of domestic enrichment in Saudi Arabia is hard to justify. The KSA is years away from operating nuclear reactors that could run on domestically enriched uranium fuel. Moreover, starting soon to build an enrichment facility in the hope of reaping substantial financial rewards as an enriched uranium exporter would be a risky business decision—especially when future market conditions are hard to predict and the prospects for lining up customers in competition with several established and highly-efficient foreign enrichment operators are uncertain.

For the time being, it would seem preferable for the KSA to gain technical and business experience extracting and processing its uranium resources, producing and marketing UF6, obtaining reliable access to enriched uranium by investing in U.S.-based enrichment, and building and operating nuclear reactors to diversify its sources of energy—all of which would provide a much sounder basis for evaluating the merits of pursuing domestic enrichment at a later stage.

The U.S.-Saudi deal currently under negotiation should therefore not provide for the construction of a uranium enrichment facility in the kingdom—at least not for now. But it should not close the door on domestic enrichment. Instead, it should call on the two parties to keep the question of fuel cycle activities in the kingdom, especially enrichment, under continuing review. A bilateral mechanism could be established that would meet on a regular basis to conduct the fuel cycle review. During the review period—perhaps 10 years—there would be a moratorium on enrichment and reprocessing in Saudi Arabia. During that period, the United States would not assist the KSA in those fuel cycle activities; nor would Saudi Arabia pursue them indigenously or with the help of other countries. At the end of the moratorium, Washington and Riyadh would make a joint determination on whether to renew or end it.

Incorporating appropriate safeguards

Like U.S. civil nuclear agreements with other countries, the U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear partnership would contain provisions designed to prevent the diversion of U.S. assistance to a nuclear weapons program. Many of these provisions are required by Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act itself or found in the guidelines of the multilateral Nuclear Suppliers Group. Among the key provisions, non-nuclear weapon states partnering with the United States must: have a safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) covering all their nuclear facilities and activities; obtain U.S. consent for reprocessing or enriching U.S.-supplied materials or for retransferring U.S.-supplied equipment or materials to third countries; and apply adequate physical security measures to U.S.-supplied nuclear materials and facilities. In addition, in the event that a cooperation partner detonates a nuclear device or violates an IAEA safeguards agreement using materials or equipment supplied by the United States, Washington would have the right to demand the return of any transferred equipment or materials.

Given concerns about the potential for nuclear proliferation in the Middle East—not to mention Saudi statements about matching Iran’s nuclear capabilities—it would be desirable for the U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear deal to contain supplementary measures. In addition to a basic IAEA Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement, which is required by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the KSA should accept an IAEA Additional Protocol, which gives the Vienna-based agency additional monitoring and inspection tools and which more than 140 countries have already accepted. It should also forswear the separation of plutonium from spent reactor fuel, ship plutonium-bearing spent fuel out of the country, and agree not to maintain an inventory of UF6 in excess of current commercial or domestic needs.

Possible domestic hurdles in the United States

A U.S.-Saudi nuclear deal could face hurdles domestically. Some Americans, such as the senators and experts signing the letters mentioned earlier, could be expected to oppose the agreement for not including a permanent Saudi renunciation of fuel cycle capabilities. Others might oppose any nuclear agreement with the Saudi government on the grounds that it had made clear its intention to acquire nuclear weapons if Iran does and had engaged in serious human rights violations, particularly the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Several factors could help overcome such domestic opposition. The perception that the nuclear deal is critical to achieving Saudi-Israeli normalization—a development likely to have wide bipartisan support in the United States—would strengthen the deal’s domestic prospects. Effective monitoring measures, the absence of authorization for near-term uranium enrichment in the KSA, and a strong case that nuclear cooperation would create American jobs and benefit U.S. industry would similarly bolster the deal’s chances.

Israeli support, or at least acquiescence, would also improve the deal’s domestic reception. Reportedly, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is prepared to go along with a U.S.-Saudi nuclear agreement, even one that provides for enrichment, presumably because he views it as critical to realizing normalization, one of his top priorities. Other Israelis, however, including opposition figure Yair Lapid, have said they would oppose a deal that allows for Saudi enrichment. Nevertheless, a deal that facilitated normalization without providing for a Saudi enrichment facility would likely be received favorably in Israel.

The rather permissive entry-into-force procedure for 123 agreements would also greatly improve the deal’s prospects. If, after a lengthy period of congressional review, the Congress fails to pass a joint resolution of disapproval—which would require a supermajority to override an expected presidential veto—the 123 agreement would automatically take effect. This is a very high bar for opponents to block the deal.

A nuclear deal involving Saudi investment in a U.S. enrichment (or conversion) company could face another kind of hurdle: domestic concern that the investment would give a foreign company or country (and specifically a country like Saudi Arabia with a tarnished reputation in the United States) undue influence in an area of national security importance. The deal could prompt scrutiny and conceivably opposition from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) or the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), both of which have statutory responsibilities to investigate cases of foreign ownership or control of U.S. businesses.

However, any reviews carried out by the NRC or CFIUS are unlikely to result in a decision to block a proposed Saudi investment. The Saudi and American entities involved in the transaction, as well as U.S. officials, would be well aware of potential concerns over foreign ownership, control, or influence (abbreviated as FOCI) and would seek to ensure, often in consultation with the reviewing organizations, that the amount of investment, the structuring of the arrangement, and the Saudi role will not rise to a level that could trigger a decision to disallow the transaction.

The civil nuclear deal recommended here would not be without controversy in the United States, but domestic opposition is unlikely to derail it.

In the kingdom, the deal described above may not go far enough for those who support domestic enrichment soon, whether for commercial reasons or an interest in having in place the infrastructure that would provide an option to pursue nuclear weapons at some future time. But an agreement authorizing an enrichment facility on Saudi soil would involve many more restrictions and potential political hurdles.

To prevent the transfer of enrichment technology—which the Biden administration considers a red line—the Saudi-based enrichment plant would have to be operated exclusively by Americans. No Saudis would be given access to the facility or would otherwise be authorized to receive enrichment technology.

IAEA safeguards would have to be more rigorous and intrusive, going beyond the Additional Protocol, with enhanced verification measures such as those contained in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action negotiated with Iran, perhaps including monitoring of uranium mining, milling, and conversion and more frequent IAEA inspector access to sensitive facilities.

Special arrangements might also be considered necessary to address the concern that the Saudi government could in the future decide to nationalize or physically take over the enrichment facility. For example, U.S. military personnel could be stationed at or near the enrichment facility as a deterrent. There has also been speculation about installing a remote shutdown mechanism or even using covert means to disable the plant in the event of a takeover.

Another complication is that a nuclear agreement authorizing the near-term construction of an enrichment plant in the KSA would attract more U.S. domestic criticism than an agreement that didn’t. A few years ago, a bipartisan group of members of Congress with strong reservations about U.S.-Saudi nuclear cooperation, including Senators Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Representatives Brad Sherman (D-Calif.) and Ted Yoho (R-Fla.), introduced a bill that would require a U.S.-Saudi 123 agreement to receive majority votes in both houses of Congress. In polarized Washington, this would make entry into force much more difficult, especially compared with the normal procedure allowing entry into force in the absence of a joint resolution of disapproval. The proposed bill did not become law, but opponents of a nuclear deal would now have a controversial new issue—the enrichment facility—to help them resurrect and build support for their initiative to make blocking the 123 agreement much easier.

Moreover, the congressional review process as well as the broader public debate on the agreement, especially its authorization of an enrichment facility in the KSA, would be highly contentious, with strong criticism of Saudi Arabia, and not just on the nuclear issue. Whether or not the agreement survived the congressional review, U.S.-KSA bilateral relations could take a serious hit.

Given these considerations—as well as the lack of any compelling commercial or nuclear energy justification for proceeding with a domestic enrichment facility at this stage—it would seem preferable to conclude a 123 agreement that stops short of authorizing near-term enrichment and instead defers the question of enrichment to a later date.

Time is running short for U.S.-Saudi and Saudi-Israeli agreements in 2024

The Biden administration would like to reach an agreement by early summer on Saudi conditions for the normalization of Israeli-Saudi relations: a U.S. security guarantee to the kingdom, a pathway to Palestinian statehood, and a U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear agreement. But time is growing short, and the prospects for finalizing agreements and gaining any necessary formal approval of them (e.g., a binding U.S. security guarantee) will deteriorate as the election year proceeds.

The continuation of the war in Gaza has impeded the U.S.-Saudi negotiations’ timely completion. It is hard to imagine agreement on the Palestinian issue being reached while the war rages. And it is hardly a propitious time for the United States and the KSA to unveil and seek domestic support for a significantly upgraded bilateral security relationship.

Washington and Riyadh (and Jerusalem) have hoped to have the U.S.-Saudi agreements and consequently Saudi-Israeli normalization wrapped up concurrently. The assumption has been that the various elements would be mutually reinforcing—for example, normalization would make nuclear cooperation with the KSA more palatable to Israel, and a U.S. security guarantee and nuclear cooperation would make normalization more palatable to the kingdom.

However, with the process delayed, consideration might be given to moving ahead with parts of the package independently when they are ready. The logical candidate would be civil nuclear cooperation, which is less affected by the war in Gaza than the other elements. A reasonable case can be made that a stand-alone U.S.-Saudi 123 agreement along the lines outlined here would serve both U.S. and Saudi interests, even in the absence of Saudi-Israeli normalization.

But if the normal congressional review and entry-into-force procedure is followed—requiring the agreement to sit before Congress for 90 days of continuous session, which can extend well beyond 90 calendar days—it will be hard to complete the review process this year unless the agreement is submitted in the next month or so. And if it is not completed during the current session of Congress, the agreement would have to be resubmitted to the next Congress in January 2025 and the 90-day continuous session clock would start again.

Alternatively, if the administration wanted to bypass the normal 90-day process and achieve an early entry into force, it could seek an affirmative vote of approval from Congress, but gaining such an affirmative vote would be politically much more difficult.

Even if the 123 agreement is finalized soon, however, bringing it into force as a stand-alone nuclear deal seems unlikely. The Biden administration may well be reluctant to submit it to Congress in the absence of an agreement on Saudi-Israeli normalization, which it believes could boost political support for U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear cooperation.

If Washington, Riyadh, and Jerusalem are unable to conclude the package of agreements by early summer—and become concerned by the prospect of not reaching an outcome this year—they could try to draft a joint statement or statements containing the key elements of what they have agreed to date. While not binding, such a framework arrangement or arrangements could increase the likelihood that the progress already achieved would be the starting point for finishing the package in the new year.

A mutually beneficial agreement that minimizes proliferation risks

A U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear agreement along the lines outlined here—authorizing a wide range of cooperative activities in the near term while deferring the issue of domestic enrichment in the kingdom—would serve both sides’ interests.

For the Saudis, it would be a major step in diversifying their economy and energy mix and advancing other Vision 2030 goals. Cooperating with the United States in building nuclear reactors, engaging in such activities as producing and marketing UF6, and acquiring a stake in a U.S.-based enrichment operation would be critical steps in helping the KSA to establish a world-class nuclear energy program and become a player in the global nuclear supply chain.

Deferring the issue of domestic enrichment in Saudi Arabia would avoid a premature and potentially risky business decision and provide time for the Saudis to evaluate a range of factors bearing on the merits of enriching domestically, including evolving market conditions, the rate of construction of Saudi reactors requiring enriched uranium fuels, and the prospects for developing a customer base for Saudi enriched uranium exports. The nuclear agreement recommended here would keep open the option of domestic enrichment for future consideration.

A U.S.-Saudi nuclear deal would also have implications for Saudi interests beyond the civil nuclear sphere. Together with a new U.S. security guarantee that is likely to accompany it, a long-term civil nuclear partnership would give a major boost to the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship, with positive effects on Saudi security and regional stability.

Moreover, deferring the issue of domestic enrichment would avoid a decision that could raise suspicions of Saudi intentions and provide incentives for other countries to engage in nuclear hedging by pursuing their own fuel cycle programs. It would also buy time for Saudi leaders to evaluate the implications for Saudi security of such developments as Israeli-Saudi normalization, a new U.S. security guarantee, and the evolution of the Iranian threat—and to consider how such developments affect any perceived need to put in place the infrastructure to produce nuclear weapons.

For the United States, a bilateral civil nuclear cooperation deal that gives U.S. companies the lead in building Saudi reactors and provides Saudi financial support for expanding U.S. domestic enrichment capacity would deliver a much-needed boost to the U.S. nuclear industry, better position it to play a major role in the anticipated expansion of nuclear energy both domestically and globally, and reduce U.S. reliance on Russia. Together with an upgraded U.S. security assurance to the kingdom, it would strengthen the bilateral relationship and have a stabilizing effect in the region.

In addition, by maintaining close U.S. involvement in Saudi civil nuclear programs, a deal would provide valuable insights into Saudi nuclear thinking and an opportunity to influence future Saudi nuclear choices. It would help ensure that the Saudi civil nuclear program would meet the highest non-proliferation, safety, and security standards; place a moratorium on sensitive fuel cycle activities in the kingdom; and preclude fuel-cycle cooperation between Saudi Arabia and other countries.

The approach to a U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear deal recommended here—particularly the deferral of the enrichment issue—would not fully satisfy those who would like the Saudis to permanently forswear the capacity to produce nuclear weapons. Nor would it fully satisfy those in the kingdom who would like, without delay, to give themselves a more credible option to decide at some future time to acquire nuclear weapons. It is a practical compromise that temporarily precludes Saudi fuel cycle activities but keeps future options open. Setting aside the difficult enrichment issue for future consideration allows Saudi Arabia and the United States to engage soon in mutually beneficial civil nuclear activities.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The author would like to thank Adam Lammon for editing and Rachel Slattery for layout.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).