Reports about the crisis facing public school teachers in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic are widespread, though a parallel crisis among the ranks of school leadership has also been quietly unfolding. While staffing has always been an uphill battle in high-need settings, challenges have been exacerbated in recent years. According to a report from the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP), the principal workforce is potentially facing a retention crisis, with large spikes in reported extra work and intentions to leave the workforce raising red flags about the sustainability of the status quo. And with the teacher labor market simultaneously under historic stress, unstable leadership could compound the problem by making retention worse.

Beyond turnover, the principal workforce’s lack of racial diversity has become a prominent issue. Similar to patterns among teachers, diversity gaps between students and principals have been growing. In 2000, 39% of students identified as non-white while 18% of principals identified as non-white; by 2017, these numbers among students surged to 52%, but only grew to 22% among principals, widening the gap by nine percentage points. Though current circumstances are challenging, a period of high turnover among school leaders also presents a unique window of opportunity to move the needle on principal diversity.

In recent years, “Grow Your Own” (GYO) teacher programs have become a popular option for improving retention and diversity in the teacher workforce, with a growing body of research and policies encouraging the adoption of these programs by districts. Yet, this type of preparation pipeline as a means of bolstering school administrator ranks remains underexplored and underutilized. In this post, we look at principal diversity gaps on a geographic level, consider GYO pipeline programs, and speculate about how GYO programs and policies could support the development of a more stable, diverse principal workforce.

The geography of principal diversity

Developing principal pipelines that create a systemic pathway for more diverse leadership could benefit schools and districts. For students of color, research suggests having a same-race administrator results in higher test scores, improved attendance, and a higher likelihood of gifted program placement. Principals of color also contribute to a more diverse teacher workforce via more inclusive teacher hiring practices, lower teacher turnover for same-race teachers, and higher job satisfaction for teachers with a same-race principal. Plus, teachers of color are more likely to be encouraged into administrative positions with a same-race supervisor, creating a virtuous loop. This suggests that principal pipelines that prioritize principal diversity could simultaneously address teacher diversity and help narrow various race-based achievement gaps for students.

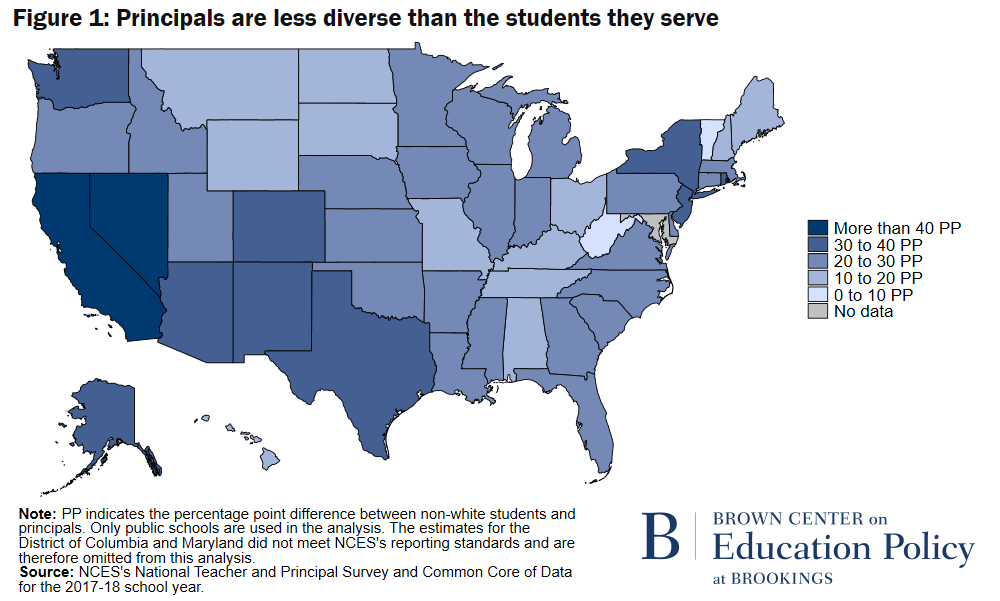

Recognizing the localized nature of educator diversity, we explored how principal and student representation differs by state using data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Figure 1 illustrates estimates of state-level principal-to-student diversity gaps as measured by the percentage point difference between non-white student representation and non-white principal representation (larger values represent greater differences in disparity).

Most states have large gaps, hovering within the 20-30 percentage-point range. A few states’ gaps are exceptionally large, including Nevada at 48 percentage points (68% nonwhite students – 20% nonwhite principals), California at 43 percentage points (77% – 34%), and Washington at 40 percentage points (46% – 6%). These gaps roughly mirror prior Brookings research examining teacher-student diversity gaps, and confirms a clear representation issue within the principal workforce in nearly all states.

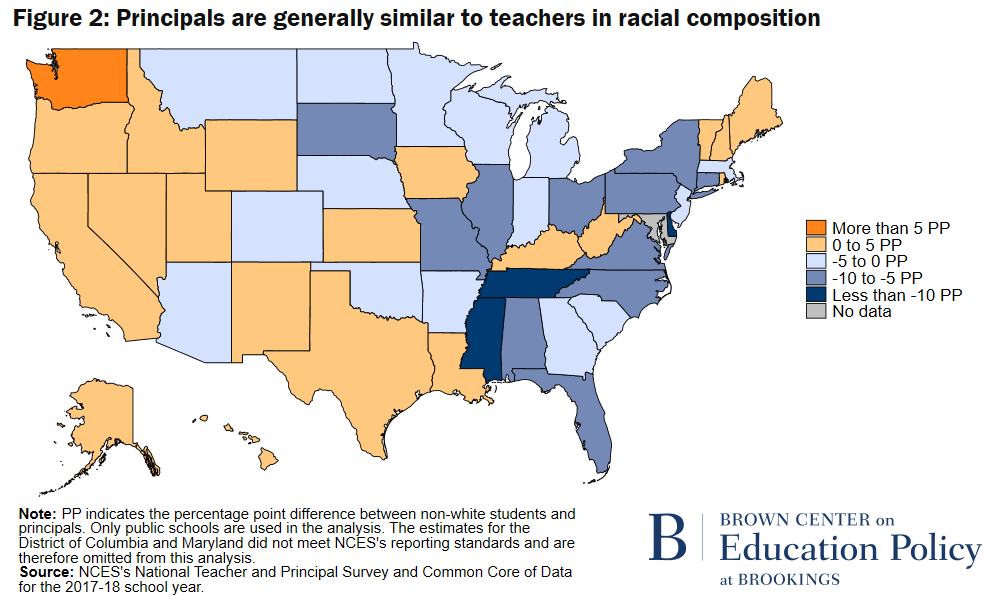

Since the principal pipeline relies heavily on the teacher workforce, it’s also useful to compare racial representation between principals and teachers. Figure 2 illustrates principal-to-teacher diversity gaps in the U.S. by state as measured by the percentage-point difference between the share of non-white teachers and non-white principals. A positive (negative) diversity gap, represented in shades of orange (blue), means that principals are less (more) racially representative than teachers.

Overall, the teacher and principal workforces of each state are relatively similar in racial composition, with 34 states falling within just five percentage points of parity between teachers and principals. But the real insight here is that 14 states have a substantially more diverse principal workforce than teacher workforce, where principals are five or more percentage points more racially diverse than teachers. Though this analysis cannot identify what these states might be doing differently to create this result, it shows more representative school leadership ranks are possible and points to places we can start looking for ideas.

Grow Your Own Principal Pipeline Programs

GYO programs are increasingly popular strategies to build out more diverse teacher pipelines. However, GYOs focused on developing school leadership are less common. Outlining teacher GYO programs can provide helpful context for understanding principal GYO programs.

Teacher GYO programs are partnerships between a school system (often districts) and teacher preparation programs (typically colleges or universities) that create a coordinated pathway to recruit, prepare, and then place teachers in schools within their communities. Some programs have specific preparation targets, such as special education teacher capacity for rural schools and indigenous language preservation. As of 2020, 47 states had some type of teacher GYO program and over half of states had a statewide policy to enable GYO pathways. The empirical literature evaluating these programs is quite slim, though the studies that do exist indicate positive outcomes, from high teacher retention rates for GYO teacher graduates to increasing the supply of teachers of color.

Principal GYO programs are similar in structure to teacher GYO programs. Principal GYO programs are partnerships between school systems and universities that create a pathway for individuals to enter school leadership. The motivation behind principal GYO programs is that, like teacher GYO programs, these pipelines will result in a supply of homegrown school leaders with increased diversity and targeted preparation.

GYO principal programs, however, are far less prevalent than their teacher-focused counterparts. Multiple localities, including Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Kansas City, Missouri, partnered with TNTP (formerly The New Teacher Project) as a part of their Pathway to Leadership in Urban Schools (PLUS) program. The findings of an evaluation of one district that implemented this PLUS program suggested that leaders who participated in the program may have contributed to improvements in student learning and to more selective teacher retention, with lower retention among lower-performing teachers.

Another principal pipeline approach by Dallas Independent School District (ISD) explicitly prioritizes diversity. Dallas ISD launched its Leader Excellence, Advancement and Development (LEAD) Department which has since created multiple programs as a part of its focus to attract diverse, high-quality principal candidates. While the Dallas ISD programs haven’t been evaluated directly, they align with what research suggests an effective principal preparation pipeline program would entail, including mentoring and working with external university programs to strengthen preparation in a way that meets the unique needs of their districts. Additionally, there are many other districts that have made it a goal to increase the proportion of administrators of color, even if they don’t yet have a formalized GYO program.

Developing GYO principal pipelines should help promote improved stability among principals. Prior research points to a link between principal effectiveness and lower principal turnover. Evidence suggests that school leaders who partake in the mentoring and coaching with current principals that GYO leader pipelines often provide report feeling more prepared for the responsibilities of school leadership. Further, recognizing the potential impact school leaders can have on outcomes from student attendance to teacher retention, efforts to develop these pipelines could have a multiplying effect on many important outcomes.

Conclusion

Though the current moment requires quick action to bolster school leadership ranks, we cannot overlook long-term strategies. Building out principal pipelines with an eye toward principal diversity in districts around the nation will be a key strategy in creating a sustainable pool of school leaders and strengthening school leadership.

Implementation of GYO principal pipeline programs could be pursued by local, state, and federal policymakers. Locally, school districts and superintendents could deepen partnerships with universities and organizations to develop GYO principal pipeline programs within their respective school districts, which could range in design to meet district-specific needs. At the state level, policymakers could support statewide GYO principal policies and funding programs, as they have done for teacher GYO programs and diversity efforts. At the federal level, policymakers could draft legislation for GYO principal pipeline competitive grant funding to support districts in their efforts to build partnerships and pipelines. Similar federal legislation addressing teachers includes House Bill 5839, Senate Bill 2367, and Senate Bill 2887. This type of federal funding could support evaluation so that the body of research and evidence regarding principal GYO programs and their impact on principal effectiveness and diversity can grow.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).