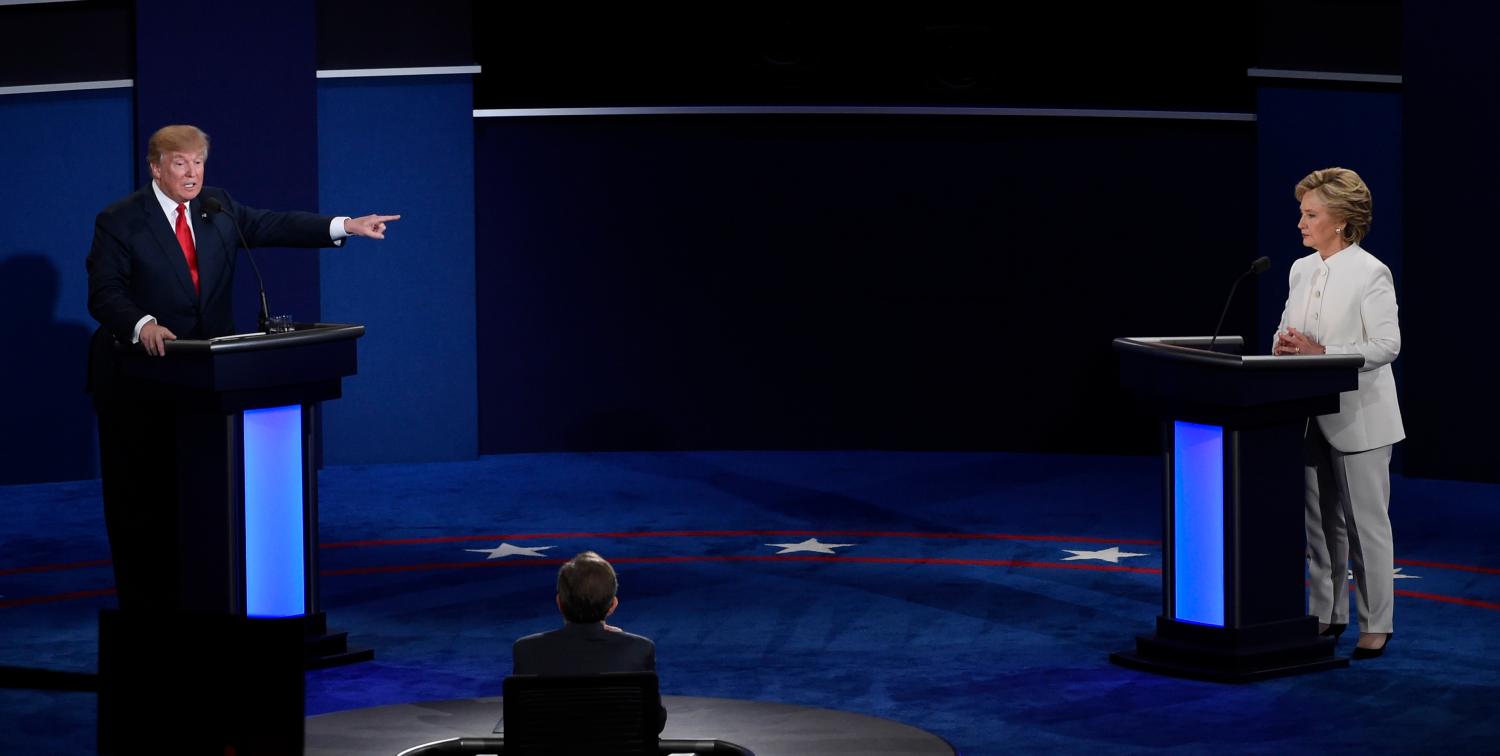

In advance of the Oct. 19 presidential debate at UNLV, The Sunday and the Brookings Institution in partnership with UNLV and Brookings Mountain West are presenting a series of guest columns on state and national election issues. The columns will appear weekly. This column originally appeared in the Las Vegas Sun.

Those working in the education policy industry, as I do, always find reasons to complain during presidential election cycles, and the bellyaching seems amplified this year. What is our complaint? That our darling area of public policy receives so little attention in the limelight of civic debate that comes with the general election.

I acknowledge these hurts are mostly irrational. Any American civics teacher could tell you that in our federalist republic, the provision of public education is under the jurisdiction of states and commonly administered by local districts, not the federal government led by the president. Thus, our complaints have just as much power in campaigns for the office as bemoaning the lack of debate on state tax policy or land-use zoning decisions.

Ironically, it is because of this distinction of powers that you’ll often hear heckles from education’s peanut gallery when presidential candidates do weigh in on policy issues, as they commonly overpromise. As examples, see Donald Trump’s promise to dump the Common Core State Standards, or Hillary Clinton’s vows to intervene in the most decrepit, lowest-performing schools. Both of these are widely known as state and local issues, and after the federal Every Student Succeeds Act passed in December, the federal government’s degree of influence over them is further from the president’s reach than during the era of No Child Left Behind.

Yet, the perennial hurts of education policy experts aren’t entirely imagined. After all, we do have a U.S. Department of Education, with a Cabinet-level secretary. Judging by these criteria alone, education policy is just as legitimate a role for the federal government as defense, foreign affairs and the treasury. Yes, that federal role is more narrowly defined in education than other policy areas, given the states’ pre-eminent authority; however, there is still a federal role and, therefore, a space for fruitful debate.

In the spirit of provoking a constructive civic debate — one that actually honors the separation between state and federal powers — I present my wish list of presidential debate topics on education policy. Regardless of the positions the respective candidates might take, coverage of these five questions would inform voters about differences they could actually make in our public education system if elected.

1. What kind of experiences and attitudes would you look for in appointing a secretary of education? The secretary is the president’s agent to carry out federal functions supporting public schools, to articulate policy positions and even to occasionally use the bully pulpit to promote change in states and districts. I see the secretary question as a useful signal for determining whether the candidate wants an insider who can work with states and districts, or an outsider coming in specifically to shake things up; whether he or she wants a technical policy wonk or more of a visionary leader in carrying out these functions.

2. Are Title I funds achieving their intended goals, and if not, what changes would you promote to improve funding formulas? Title I funds are federal dollars going to high-poverty schools, intended to reduce inequalities in school spending that once were commonplace across schools and districts. Yet there is widespread concern that Title I funding formulas actually reinforce inequalities across states, promote ineffective spending, and add layers of compliance-focused bureaucracy to state and local education agencies. This question is important because these funds were the primary purpose behind the original 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act that involved the federal government in public schools in the first place. And it isn’t the only area where federal intervention has produced unintended consequences for schools (e.g., standardized testing). Responses here would reveal how the candidates view prior interventions, and how the federal role could evolve.

3. Has the sharper focus on transparency in higher education regarding student employment and loan payoff during the Obama administration helped improve students’ chances of upward social and economic mobility? Embedded in this question are assumptions about the role of college as a gateway to the middle class, the costs of higher education and the power of information to bring about desired social change. Because the Higher Education Act is the next major federal education law due for reauthorization, and the Department of Education’s recent changes here have shifted the balance of power from historical norms with institutions of higher education, responses to this question would indicate how the candidates intend to leverage the government’s power to create more or less change.

4. Which federal education programs would you expand and which would you shrink? There are dozens of programs, and they’re not all administered by the Department of Education. Generally, they are not well-coordinated and occasionally work at cross-purposes. So this question would illuminate each candidate’s prioritization process. For example, does the candidate think we are better off advancing innovation in education through a top-down program in the Department of Education, or through a program like the State Longitudinal Data Systems or charter schools, both of which theoretically could help bottom-up innovation? The next president will have significant influence over which programs flourish and which will flounder over the next four years, and knowing his or her preferences is valuable information for all voters.

5. Because this is my own wish list, I would be remiss without throwing in this final query: How much would you increase funding for federal research in education?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).