It is time to broaden the national dialogue about educational opportunity for incarcerated students. At a recent event at the Center for American Progress, Secretary of Education John B. King, Jr. spotlighted the administration’s Second Chance Pell initiative, a program that will allow eligible prisoners to receive Pell Grants to pursue higher education opportunities at one of 67 two- or four-year institutions nationwide. Touted as a strategy for reducing recidivism, facilitating re-entry, and rebuilding communities affected by incarceration, the program represents an evidence-based approach to securing public safety and promoting social mobility.

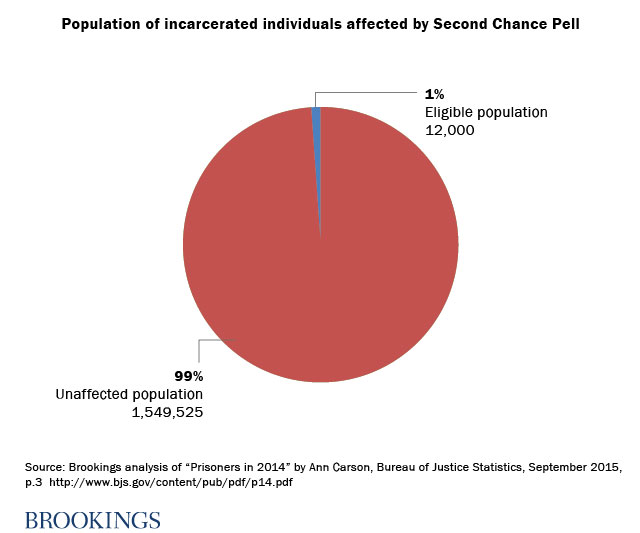

Second Chance Pell is technically an experimental initiative of the Department of Education, and as such, the scope of the program is relatively limited. The Department of Education estimates it will affect roughly 12,000 incarcerated individuals—just about 1 percent of the estimated 1.5 million individuals incarcerated at the state and federal levels. Rather than stating concrete policy goals, the initiative poses a set of research questions: to “test” whether participation in high-quality educational opportunities increases after access to financial aid for incarcerated adults is expanded and to “examine” the impact of waiving the restriction on providing Pell Grants to incarcerated individuals on academic and life outcomes.

The administration’s actions are limited because the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act expressly prohibits individuals incarcerated in federal or state prison from receiving Pell grants. Although the act passed with broad bi-partisan support in 1994, the peak of the tough-on-crime era, it has since become the subject of scrutiny and criticism from reformers on the left and right.

In an attempt to improve criminal justice reform with evidence-based policy, Congress created the bi-partisan Charles Colson Task Force (CCTF) in 2014. After two years of research and inquiry, the CCTF issued a report that urged Congress to repeal all “federal collateral consequence laws, regulations, and practices that, without a public safety basis, bar civic participation and access to programs.” The task force specifically identified a repeal of the prohibition on Pell grants for incarcerated students.

This recommendation is rooted in a body of solid, social scientific research. One oft-cited study from the RAND Corporation found that on average, inmates who participated in correctional education programs had 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than inmates who did not. The study also found that among inmates who participated in academic or vocational correctional education programs, the odds of obtaining employment post release were 13 percentage points higher than for those who had not participated. Although the report suggests that receiving correctional education while incarcerated reduces an individual’s risk of recidivism, the authors identify a need to collect additional evidence and call for studies that “identify the characteristics of effective programming in terms of such variables as curriculum, dosage, and quality.”

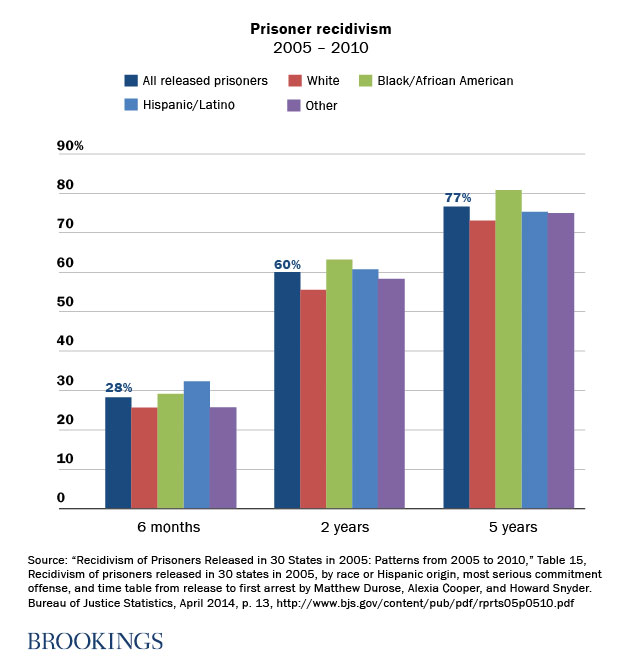

Expanding educational opportunity to incarcerated students is just as much a matter of rehabilitating individuals as it is a matter of fostering safe communities. Current rates of recidivism in the United States stand at over 75 percent after five years of release. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, given that the majority of incarcerated individuals will one day be released, high recidivism rates pose a substantial risk to public safety.

The twin goals of reducing recidivism and securing public safety with evidence-based policy should unite Republicans and Democrats. Although available evidence indicates the value of expanding educational opportunities to incarcerated students from a public safety perspective, implementation of the Second Chance Pell program will provide additional data that inform an evidence-based approach to criminal justice reform.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Creating educational opportunity for incarcerated students

July 15, 2016