The story of the Democrats’ stinging defeat in the 2014 midterm elections is as well-told by the millions of Americans who did not cast ballots on Election Day as by those who did. The United States Election Project estimated voter turnout at 36.2%, the lowest since 1942. In his post-election press conference, President Obama addressed the nearly two thirds of Americans who did not vote by saying, “I hear you too.”

He may well have had those voters in mind when he issued his executive order to stop the breakup of the families of undocumented immigrants. A large share of the potential voters who stayed home were Latinos, many of them dispirited over Congress’ failure to act on immigration.

According to the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2014 Post-Election American Values Survey, which re-interviewed 1,399 respondents who had been contacted in a pre-election poll, Latinos comprised just 8% of all voters—but 22% of non-voters. African-Americans were roughly equally represented among non-voters (12%) and voters (11%). Whites made up a larger share of voters (73%) than non-voters (56%.)

The non-voter pool was also overwhelmingly young: Millennials, those of ages 18 to -34, made up 47% of the non-voters and just 17% of voters. On the other hand, 54% of those who reported voting were over the age of fifty.

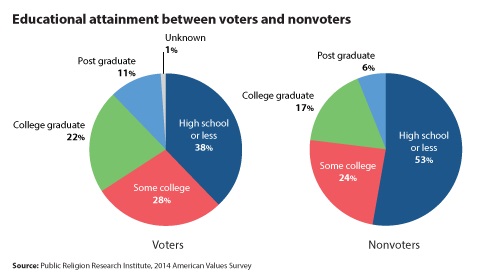

The electorate was also skewed by education and class: those with more schooling were much more likely to vote. The survey found that 53% of non-voters did not attend college, compared with 38 % of those who said they voted. Among non-voters, 44% made less than $30,000 a year; among voters, only 26% were in that lower income group. At the other end of the socio-economic scale, 23% of non-voters but 33% of voters had college degrees or advanced degrees. Respondents earning $100,000 or more annually accounted for 7% of non-voters, but 17% of voters.

Not surprisingly, partisans were more likely to cast ballots in the mid-terms than Americans without partisan leanings. But Republican partisans turned out at a higher rate than Democrats. The survey found that Republicans made up 21% percent of the non-voter pool, but 28% of those who said they voted. Democrats accounted for 31% of non-voters, and 34% of voters. Independents accounted for 42% of non-voters, but only 33% of voters. There was an even stronger skew ideologically, in favor of conservatives. Liberals accounted for 26% of non-voters compared with 25% of voters. Conservatives, on the other hand, made up 34% of non-voters but 42% of voters. Moderates, like independents, were the most likely to stay home. Among non-voters, 38% called themselves moderate; among voters, only 31% did.

This produced a net advantage for Republicans on Election Day. In the post-election survey, those who said they voted split 46% in favor of Republican House candidates and 45% for Democrats. This produced a 52% to 48% two-party margin in favor of the Republicans. But in their interviews before the election, the non-voters favored Democratic House candidates, 43% to 39% percent.

The non-voters in this election cycle issued a warning to both parties.

In 2010, Democrats lost in a landslide because of a significant demobilization of key parts of their 2008 electorate. They were determined to avoid the same fate in 2014 and invested heavily in voter turnout efforts. These had an effect in some states, particularly with African American voters. But on the whole, as these figures and the exit polls suggest, many of the Democrats’ core constituents again avoided voting in the midterms. The party will face a long term problem if it has the capacity to win presidential elections but then faces sharp losses in the House, the Senate and in state governments in the off years.

Republicans had one repetitive but effective theme in 2014: they cast the election as a referendum on the president and turned out his opponents. The Democrats lacked a unifying theme and in its absence, all their organizing efforts proved insufficient. As a Republican operative told the National Journal’s Amy Walter, “You can’t win on turnout if you are losing on message.”

The Democrats were tongue-tied on the issue that mattered most: the economy. And the non-voters, if anything, cared even more about economics than the voters did. The survey found that while 36% of voters listed the economy as the issue most important to their choice, 41% of non-voters did—not surprising in light of their economic circumstances. Democrats were reluctant to tout Obama’s significant economic achievements—the broad recovery from collapse, the drop in the unemployment rate to below 6%, high stock prices and low gas prices. They feared that doing so would make them seem out of touch with the many Americans whose wages are stagnating. But neither did they present a broad program for lifting incomes and living standards. Solving their economic dilemma is the Democrats’ key task between now and 2016.

But Republicans have no reason to rest easy. The 2016 electorate will in no way resemble the conservative tilting voter pool of 2014. The participation of the young will increase, as it did between 2010 and 2012. Latino voters will almost certainly be back in large numbers, motivated, perhaps, by the battle for immigration reform that Obama initiated. And the presidential electorate will be less affluent. Republicans, too, need a rendezvous with voters disappointed by their economic circumstances.

It is common for politicians to be encouraged to hear the voice of the voters. But as they look forward to the next election, both parties may want to pay even closer attention to the people who stayed home.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What the Non-Voters Decided

December 1, 2014