Editor’s Note: The

U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit blog series

is a collection of posts discussing efforts to strengthen ties between the United States and Africa ahead of the first continent-wide summit. On August 4, Brookings will host “The Game Has Changed: The New Landscape for Innovation and Business in Africa,” at which these themes and more will be explored by prominent experts. Click here to register for the event.

Last year while visiting Cape Town in South Africa, President Obama announced plans for the first continent-wide U.S. African Leaders Summit, scheduled for August 4-6, 2014. The summit provides an opportunity for the Obama administration to open a new chapter in U.S-Africa relations, moving from interaction on the bilateral level to a continent-wide engagement. President Obama has previously been criticized for not reaching the same level of engagement with Africa as Presidents Bush and Clinton, but his second term has coincided with an effort to ramp up U.S.-Africa relations. In June 2012, Obama launched the White House strategy “toward” sub-Saharan Africa, and the president’s budget for 2015 shows his support for the region. The U.S.-Africa summit, however, now affords the United States an unprecedented opportunity to build a strategy “together” with Africa.

Recently, the Africa Growth Initiative (AGI) has reviewed the components—the organization, frame and communications strategies—of three longstanding Africa summits in order to inform the designers of the U.S. version. In this comparison, AGI chose China, the European Union (EU) and Japan; some of Africa’s other key trade and investment partners. Leading up to the summit in August, the Africa Growth Initiative will also compare the position of the United States and these partners in terms of trade, foreign direct investment and other engagement with African countries. Obtaining a maximum level of foreign policy action and results from a two-day summit with nearly all of the African heads of state in attendance is an enormous undertaking. However, the other summits have had plenty of time to work out the kinks. Thus, they provide excellent examples of a successful summit for the U.S. organizers. In this first installment, AGI examines and highlights the features of those summits that could strengthen the U.S.-Africa partnership: frequency, sustainability, inclusivity, transparency and accountability.

The full African Leaders’ Summits comparison data is available in this annex.

Important Summit Design Features and Recommendations

Design Feature 1: Frequency and Sustainability

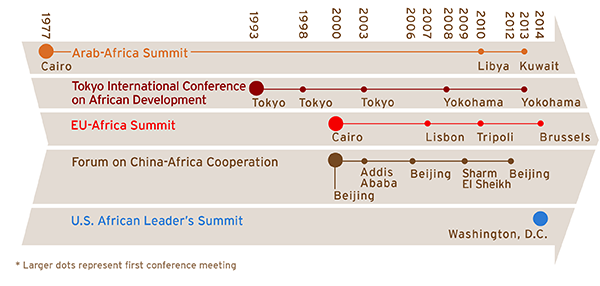

The United States is playing catch-up in terms of using a continent-wide leaders’ summit to frame its strategy with Africa.[1] Japan, China and the European Union have all maintained long-running Africa summits. Japan’s Tokyo International Conference for African Development (TICAD) started in 1993 and has met every five years since. China’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the EU-Africa summit both started in 2000. FOCAC has met every three years since, while the EU-Africa summit has taken place three times since the first gathering (figure 1). Other countries have held similar summits, including India, Brazil, South Korea, South America and Turkey. While the United States deserves credit for its yearly Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) trade ministerial, which alternates between United States and an AGOA eligible country in Africa, it covers fewer themes than the EU-Africa, FOCAC and TICAD summits. For the first U.S.-Africa Summit, Senior Director of African Affairs at the White House Grant Harris recently announced that the theme will be “Investing in Africa’s Future.”

Figure 1: African Leaders’ Summits Timeline

The ultimate goal of the China, EU and Japan summits has been to frame a sustainable, lasting engagement with Africa. The main products of each of the summits are a joint summit declaration and a joint summit action plan. Since China, the EU and Japan hold meetings every three to five years, they are able to review and update action plans and commitments on a regular basis.

Recommendation: The United States should prioritize the sustainability of the U.S-Africa summit. The first priority for the African Leaders’ Summit should be to build a framework for a U.S.-Africa partnership that will stand the test of time. The most important products are the declaration and the action plan; these documents should present a clear plan of how the U.S. will engage Africa going forward (through further summits or otherwise). A joint communiqué should contain action items that will be measurable and tractable for substantial progress by the next summit, including the announcement of a date and location for the next leaders’ summit, a joint follow-up committee, and a date for the first follow-up committee meeting. The sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in September would be a good forum for the first follow-up meeting of the committee; a meeting soon after the event will send a clear signal that the action items will be taken seriously by all parties. The U.S.-Africa Summit Policy Liaison Office of the State Department is a logical entity to manage future summits and could transition into a permanent entity similar to the TICAD secretariat.

China, the EU and Japan have all learned to start planning for the next summit three to five years ahead of time, with multiple joint meetings and preparatory work in between summits. More preparatory time helps them to bring greater perspective and more voices to the table, which leads us to our next key summit design feature.

Design Feature 2: Inclusivity

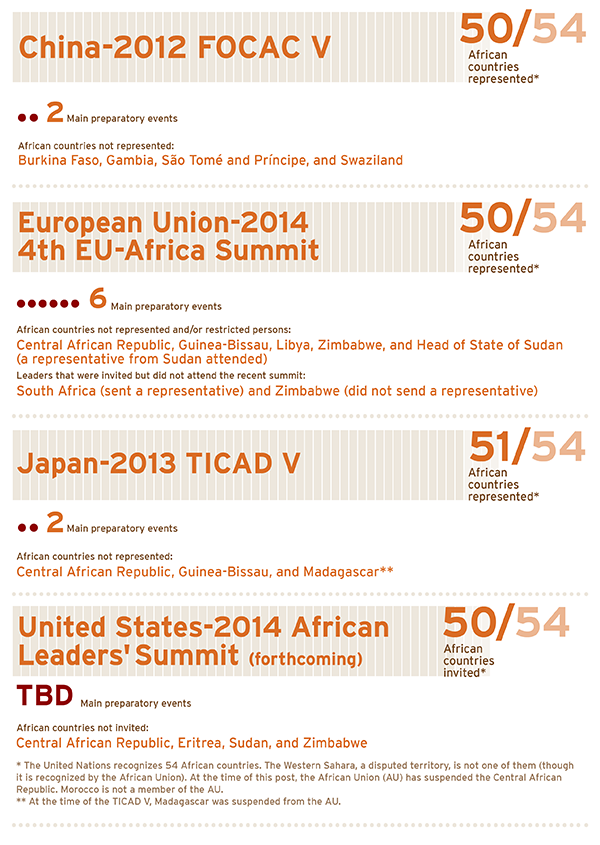

As shown by the figures in table 1, a major challenge is inviting all of the African leaders to the summit so they can be included in the discussions. Another challenge is including the multitude of voices from outside the leadership: civil society, businesses, youth leaders and women. Both China and the European Union have foreign policy challenges with African countries that have impacted summit attendance. For example, China does not invite the leaders of African countries that recognize Taiwan as a sovereign nation to FOCAC (this includes Burkina Faso, São Tomé and Príncipe and Swaziland and, previously, the Gambia). Early in 2014, the European Union faced a backlash for its summit invitation list. Ahead of the EU summit, the African Union (AU) proposed a boycott of the event after hearing that Morocco, not a member of the AU, was invited while the leader of Sudan (an AU member) was excluded due to human rights abuses. However, only Zimbabwe’s President Mugabe followed through with the proposed protest, although South Africa’s President Zuma also did not attend the summit, vaguely citing “other commitments.” President Mugabe’s boycott was ultimately for more personal reasons. His wife, Grace Mugabe, was slated to accompany the president to the summit, but was denied a visa.

The U.S. is likely to face similar challenges to the EU and China. The U.S. has invited 50 out of the 54 countries in Africa recognized by the U.N. (Madagascar was recently added) to the upcoming summit, but has excluded the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Sudan, and Zimbabwe from the list. Why? The White House has stated that it has selected members that are in good standing with the AU and the United States. Here are some more details on country standings: first, the Central African Republic is currently suspended from the AU; second, the U.S. has concerns about the status of democracy in Eritrea; and third, the leaders and government officials of Sudan and Zimbabwe currently face U.S. sanctions. In total, 51 delegations are scheduled to attend, which include the African Union chairperson.

Table 1: Key Statistics on Inclusion at African Leaders’ Summits

Beyond the guest list, past summits have used other techniques to build a sense of partnership and inclusiveness among African nations. Joint preparatory events that include African senior officials and ministers have been used by China, the EU and Japan to prepare and consult on the key themes and issues that will be discussed at the summit. Preparatory events help the host countries cover more summit themes by allowing more time for discussion with ministers, senior officials, diplomats and other stakeholders. The FOCAC V and TICAD V summits used at least two preparatory events, while the European Union summit held six meetings broken down by sector. The U.S. joint ministerial meeting on energy from June 3-4, 2014 is a good start for the U.S.-Africa partnership.

In addition, China, the EU and Japan all chaired their summits jointly, typically between the host country/region at leader level and either the African Union president or chairperson of the African Union Commission. Japan also co-chairs with the other TICAD organizers, which include international multilateral organizations. Bilateral meetings have taken place at all three summits in the comparison, but these run the risk of offending some countries if they are not scheduled to meet the president. Prime Minister Abe notably met with all heads of state and government that attended the TICAD V summit, while the EU provides a channel for the European Parliament to engage with African leaders at the Pan-African-European Parliamentary summit.

Recommendation: The U.S. should include as many African voices as possible to build the credibility of U.S.-Africa engagement: The U.S.-Africa summit is an opportunity to shift from having a strategy toward Africa to having a strategy together with Africa, with its leaders and other stakeholders. If the United States cannot invite a country’s leader for political reasons, it should strive to have at least some representation at the forum. The United States can use the EU summit as an example of how to manage invitations to ministers or other non-head of state representatives. For example, while Omar al-Bashir was subject to EU sanctions, Minister of Foreign Affairs Ali Ahmed Karti was able to represent the Sudan at the summit. Given the U.S. administration’s current efforts to help resolve the crisis in the Central African Republic, inviting representatives from the Bangui authorities could help continue the dialogue.

A recent article by Stephen Hayes, from the Corporate Council on Africa, noted that the President will not be meeting with any of the presidents one-on-one; rather, there will be an “interactive dialogue” to conclude the summit. President Obama may want to reconsider skipping the one-on-one meetings and take an example from Japan’s Prime Minister Abe, who met with all of the attending African heads of state at the TICAD V in 2013. The upcoming summit provides access to nearly all of the leaders of Africa, especially small and infrequently visited nations, and bilateral meetings help to instill confidence and credibility in United States. This is a diplomatic and symbolic opportunity that should not be missed. Bilateral meetings with all of the leaders may seem like a lot, but not all of the leaders will be able to make it, and the meetings can be spread out before and after the event. President Obama wants to build a true strategic partnership with Africa; planners should consider adding an extra day for the specific purpose of extending this important gesture. However, if the time constraints are too binding, President Obama should consider a compromise and meet with the leaders of the African Union and the regional economic communities.

Given that most of Africa’s leaders are men, the U.S. summit designers should look for innovative ways to build more gender balance into the summit itself. Among the invited African leaders, only two are female (Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia and Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, chairperson of the African Union Commission) and of the U.S. Cabinet and Cabinet-ranking positions there are six women out of 22 positions. One proposal is to acknowledge the gender imbalance in the summit declaration and make a commitment to improve, with tangible benchmarks for the next forum. The U.S.-Africa summit should strive to include the voices of women as well as other key stakeholder groups (e.g., civil society, business and youth).

Design Feature 3: Transparency and Accountability Features

In order to increase transparency, the fourth EU-Africa Summit and FOCAC V used economic and social stakeholder meetings before their summits to allow a review of themes and action plans. The TICAD summit took a different approach to civil society engagement and allowed stakeholders to register to attend the summit plenary events. In addition, TICAD V held official public side events and information booths. Well ahead of the summit, Amnesty International USA, Freedom House, Front Line Defenders, Open Society Foundations and the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights will host a U.S.-Africa Civil Society Forum on June 18-20. Other civil society groups and D.C-based think tanks are planning events around the summit, including the Africa Growth Initiative.

In terms of press access, China uses official press conferences to convey information about the summit discussion (information on press access is difficult to find on the FOCAC website). The EU and Japan, on the other hand, have readily available press guides on their websites. They allow registered press to access scheduled media opportunities (e.g., arrival and departures of leaders, opening discussions and press conferences).

After the summits, follow-up mechanisms increase the participation of African nations and hold all countries (host or otherwise) accountable to commitments. Joint follow-up meetings are used by all three summits. Japan has a TICAD Secretariat, managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ director-general for Foreign Affairs. The secretariat is a permanent department that manages the summit and follow-up actions. China has a similar mechanism, the FOCAC Chinese Follow-up Committee composed of 27 Chinese ministers. In addition to joint meetings, the Chinese and Japanese summits were followed by presidential visits to the African Union and African countries. Each of the summits uses a results-based framework to guide the action items from the summit declaration. Japan is the only summit that has a progress report website, which allows the public to track the progress of the TICAD implementation matrix. Summit websites store summit information and documents for access by the public after the event. Currently, Japan has the most information available across two websites (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs TICAD page and the conference page). The EU also provides a lot of public information, again on two websites (EU Council and EU-Africa Partnership), while China’s information is mainly limited to official statements.

Recommendation: The U.S. should participate in stakeholder forums and provide public information and progress reports to hold the U.S. and summit participants accountable: Washington D.C. civil society has taken on the task of organizing a civil society forum. The White House should consider participating and consider any suggestions that result from the discussion.

The United States can foster transparency by developing a summit website where civil society, press and other stakeholders can learn more about the event in one location. It is very likely that a U.S. web page is already in the works at the White House or State Department. The web designers should consider how best to consolidate information into one central location on the web and include links to the additional forums and events (such as the yearly AGOA trade ministerial, the Young Africa Leaders Initiative gathering and the business forum). The other summits often do not consolidate information and have multiple summit sites, so the U.S. would be leading the way. In addition, following the summit, the Obama administration should consider Japan’s model and create a permanent summit site that houses a progress chart for action items that is updated on a regular basis.

Certainly the long-running EU-Africa, FOCAC and TICAD summits set a high benchmark for the first U.S.-Africa Summit. While President Obama should be commended for taking on the endeavor of the first one, in the next few months the administration should continue improving the summit design and implementation together with African counterparts.

[1] The first continent-wide partnership between a regional group and Africa was the Afro-Arab Summit. While the Arab League was the first mover on a summit style of engagement with Africa, it did not meet again until 2010. In 2013, the Afro-Arab summit finally put forth commitments, including $1 billion in concessional loans from Kuwait to African countries over the next five years.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit: Building a Strategy Together with Africa

June 18, 2014