In his State of the Union address, President Obama remarked that few steps are “more effective at reducing inequality and helping families pull themselves up through hard work than the Earned Income Tax Credit.” The latest Census Bureau figures on the anti-poverty effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC) confirm their substantial impact on the well-being of families and communities across the country.

According to the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM)—a more nuanced measure of poverty than provided by the official definition—the poverty rate would have been 3 percentage points higher in 2012 without the EITC and the refundable portion of the CTC. For children, the impact of these credits was even greater, effectively lowering the child poverty rate by 6.7 percentage points.

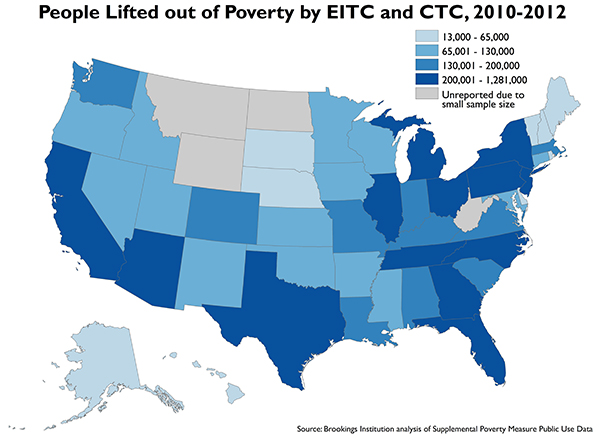

The poverty alleviation effects of these refundable credits are shared across the country, benefiting every state and the District of Columbia. The map below illustrates the average number of people kept out of poverty by the combined impacts of the federal EITC and CTC using the most recent data available. (Due to sample size issues, the map presents estimates of the average annual impact of these credits based on three years of Current Population Survey data, from 2010 to 2012.)

Less populous states like Vermont and Alaska each saw more than 10,000 residents lifted out of poverty by these credits (13,000 and 16,000, respectively). In 31 states, the number of residents lifted out of poverty by the EITC and refundable CTC exceeded 100,000, reaching as high as 1.3 million in California.

The anti-poverty impact of the EITC alone ranged from 9,000 residents in Washington, D.C. to 831,000 in Texas, where more than half of those residents were children. (See this table for detailed state data.) In addition, for the many states that have their own version of the EITC, the combined anti-poverty impact of the federal and state credits would be even greater than what is captured by the SPM, which currently only accounts for the federal provision.

Part of what makes the EITC effective as a poverty alleviation tool is its responsiveness to changes in the economic cycle (bolstered in recent years by targeted expansions) and to the changing geography of poverty in the United States. Because this benefit is administered through the tax code, the distribution of EITC recipients has tracked closely with shifts in the location of the low-income population over time. As the low-income population rapidly suburbanized in recent years, so, too, did the geography of EITC recipients, providing an important benefit to working families in struggling suburban communities that are otherwise ill-equipped to address growing need.

However, the EITC could work better for some workers, both as a poverty alleviation tool and as a work incentive. Of the more than 26 million taxpayers who claimed the EITC in Tax Year 2012, 6.1 million were childless workers or noncustodial parents. Under current law, only workers between the ages of 25 and 64 can claim the so-called childless worker credit, and both the anti-poverty impact and work incentive aspects of this credit are dampened by its comparatively small size ($487 maximum in Tax Year 2013, compared to $6,044 for families with three or more qualifying children) and the fact that these workers phase out of eligibility much sooner (at $14,340 for single filers and $19,680 for married filers, compared to $46,227 for unmarried filers or $51,567 for married filers with three or more kids).

Accordingly, in his State of the Union address, President Obama also called for strengthening the EITC for workers without qualifying children (as have policymakers on both sides of the aisle) to make it more effective at incentivizing work and making work pay. As proposals evolve and are debated, we will release estimates of the impacts of potential expansions to the credit in the coming weeks, and how they would play out across different states and metropolitan areas.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

An Anti-Poverty Policy that Works for Working Families

February 11, 2014