EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The 21st century is marked by global interconnections. People, capital, information and goods all flow across borders at ever-increasing rates. By 2030, not only will emerging market economies contribute 65 percent of the global GDP but they will also be home to the majority of the world’s working age population. As national and international businesses increasingly compete for the best graduates in emerging market economies, skilled young people are rapidly migrating from Asia, Africa, and Latin America to provide much needed talent in the face of aging workforces in Europe and North America.

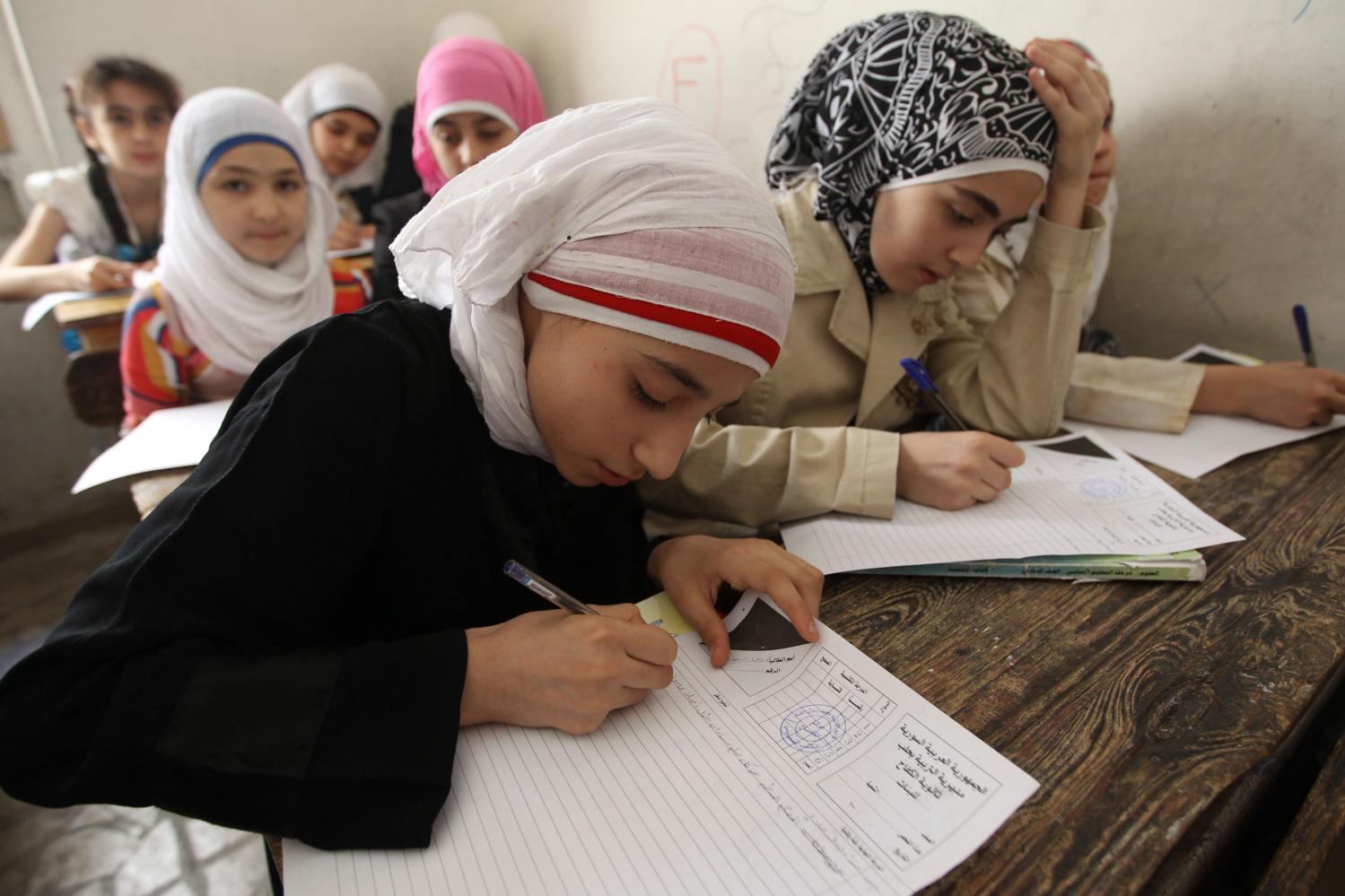

It is clear that the skills and talents of youth in the global south will be the engines of the world’s future growth and prosperity. But, critically, an education crisis in these regions threatens this very possibility. In too many locations, parents and governments are unable to provide young people with a quality education and existing international assistance programs are not coming close to addressing the magnitude of the problem. A quality education for all young people, especially those in the global south, is a good for which there is a global public interest and it is time to ensure that all that benefit from it can play a role in ensuring its provision.

It is clear that the skills and talents of youth in the global south will be the engines of the world’s future growth and prosperity. But, critically, an education crisis in these regions threatens this very possibility. In too many locations, parents and governments are unable to provide young people with a quality education and existing international assistance programs are not coming close to addressing the magnitude of the problem. A quality education for all young people, especially those in the global south, is a good for which there is a global public interest and it is time to ensure that all that benefit from it can play a role in ensuring its provision.

Yet conventional wisdom states that national governments should fund and deliver this “public good” through state controlled public education systems. However demographic shifts will put a disproportionate burden on the countries whose systems are least able to cope. The core thesis running throughout this report is that the private sector, who have most to gain (or lose) from weak education systems compounded by demographic shifts, should engage more fully in solving this education crisis through a combination of funding and capability.

There are at least four reasons why a compelling business case can be made for private sector investment in global education. First, new action is urgently needed to improve education systems in emerging market economies and low-income countries. It is the children born today whom companies will be recruiting to their ranks in 2030, and the vast majority of these new employees will have been educated in weak education systems in Asia, Africa or Latin America. Currently, the United Nations estimates that there is an annual $38 billion external financing gap for basic and lower secondary education in these regions between what governments can reasonably be expected to fund and what international aid donors are likely to support. Today, this financing gap seems unlikely to be addressed, and indeed it may even get worse. Corporate giving to global health is 16 times what it is to global education. While governments and international aid donors must be pushed to do more, new actors are clearly needed to advance the status of education around the globe. Business has a vested interest in helping education systems develop the competencies of young people and, we argue in this report, it may be time for corporations to invest accordingly.

The inability to secure future talent with the right skills and to manage talent-related costs keeps firms from being able to quickly scale up their operations to meet demand in new locations and to launch new products and services.

Second, access to a good-quality education is a strategic growth constraint for business that has a direct impact on the bottom line. The inability to secure future talent with the right skills and to manage talent-related costs keeps firms from being able to quickly scale up their operations to meet demand in new locations and to launch new products and services. In a global survey of over 1,000 CEOs, almost 30 percent said that talent constraints kept them from pursuing market opportunities, and that number jumped to over 50 percent among business leaders in countries that belong to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Labor costs are increasing, and in the same survey 43 percent of CEOs said talent-related expenses, including turnover, have a negative impact on their firm’s growth and profitability. Companies also bear significant costs to compensate for poor-quality education and the low skill levels of graduates, including investing in remedial training programs. In India alone, for example, in one five-year period information technology companies almost doubled the amount they spent on training employees, from $1 billion in 2007 to close to $2 billion in 2011.

Third, there is in fact a significant return on investment in education, as well as the potential to close a major value gap. Modest early-stage investments to ensure that each child attends school, remains in school and learns in school can yield significant economic returns. Indeed, using data from a “typical” Indian company, we have found that $1 invested in education today returns $53 in value to the employer at the start of a person’s working years. Furthermore, these investments have broad-reaching effects on the opportunity cost for “lost talent”—namely, young people who do not survive, due to preventable child mortality, let alone thrive and make it through the education system—and thus have a significant impact on a country’s overall economic performance. In India alone, nearly two-thirds of children born each year do not finish secondary school for a plethora of largely preventable reasons. In pure economic terms, this represents an opportunity cost of over $100 billion to national annual economic output, or about 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Fourth, innovative new vehicles for business investment in social sectors are emerging, demonstrating that the future economic value of tomorrow’s talent could be positioned as an attractive investment opportunity for today. Where a business case can be made to investors, it is perfectly possible to channel significant private sector resources to help solve public problems. Lessons from innovative financing models, whether from global health or prison recidivism, can provide a useful starting point for exploring how business could invest in public education systems in emerging market economies and the developing world. Ultimately, good-quality education for all young people is a good investment not only for governments and individuals but also for business, as the analysis of this report explains. Forward-thinking corporations must now engage further upstream in the talent pipeline and begin to “backward integrate” to augment the talent pool. What is needed now is a concerted and collective effort to develop new models of private financing for the public education challenge around the globe; not to privatize education but to ensure that every child, irrespective of background, has access to a fully funded, good-quality education. National governments should think about how fiscal incentives could be used to help attract and reward private corporations that embrace a long-term investment mindset toward talent development.

This challenging situation calls for nothing short of global collective action. We urgently need efforts to quantify the future economic value of human potential and to tie it to financing models that leverage both economic and societal returns on the investment of capital. The future prosperity of our global economy depends on our ability to recognize our shared responsibility in providing quality education and act with new energy to invest in its provision in emerging market economies and the developing world.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).