It is no secret that FIFA has been mired in governance and corruption scandals for many years. The challenges keep piling up as the man at the helm, Sepp Blatter, clings to power indefinitely, illustrating the extent to which some international sports organizations lag behind many countries in terms of democratic governance standards. As I argued in 2010 during the World Cup held in South Africa, FIFA is a multibillion dollar organization that profits handsomely at the expense of development of host countries.

Fortunately, the absence of governance in FIFA itself has not fatally damaged the fun and beauty of the game. Most of the World Cup games in Brazil have been exciting and raised enormous interest and passions around the world, even in unexpected places like the United States, where its first round game against Germany drew more online viewers than the NBA finals.

Yet skeptics remind us that, ultimately, it is all about money. And, yes, plenty— including FIFA’s lack of governance and its head’s perpetuation of his own power—may be about money. But is money the main driver of soccer success for a national team in the World Cup?

Money Doesn’t Always Talk

A number of analysts and organizations making predictions about the World Cup say that it is. In fact one prominent financial firm, ING, utilized the monetary market value of the national team (aggregating the market value of each player) to predict that the World Cup winner would be Spain, the highest valued national team at close to $1 billion!

Or perhaps money matters in other ways, such as how large the country’s economy is, how well paid the team manager is, or whether the national team was able to recruit a foreign manager. We also hear that oil riches might have bought the right to host the World Cup, as has been said of Qatar, or can buy a top European football club. But do national teams from resource-rich countries perform better at the World Cup?

Beyond money matters, we read about population size as a critical determinant (much larger potential pool of soccer players), and also about the “luck of the draw.” When the lottery took place to assign the 32 World Cup teams to the eight groups for the first stage, many bemoaned that their national teams had been assigned to a “group of death,” while others were placed with weaker contenders and, thus, seemingly easy groups.

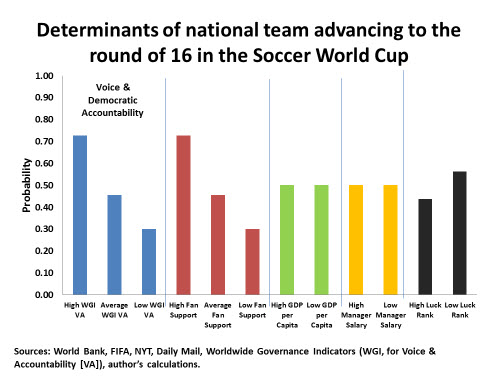

Analyzing the statistical evidence provides some surprising insights. It turns out that in looking at what differentiates success from failure in advancing to the second stage (round of 16) of this year’s World Cup, money does not seem to make a difference. Neither the monetary value of a team, nor the salary of the team’s manager (nor whether the manager is a national or foreigner) matter statistically. Controlling for other factors, the size of a country’s population or economy does not make much of a difference either. In addition, whether the country is resource-rich or not has no impact on the performance of the national team whatsoever.

Some of these statistical results would not shock those who watched the modestly valued Costa Rica advance by sending wealthy Italy home, or those who witnessed highly paid powerhouses such as England, Spain and Portugal also exit the World Cup early.

Interestingly, the “luck of the draw” regarding the caliber of the rivals each country faced in their first stage groupings of the World Cup, does not matter statistically at all either.

Governance Matters

If none of these commonly mentioned factors make a difference in explaining World Cup success, then what does matter? Our statistical analysis points to two relevant determinants.

First, the quality of democratic governance of the country is significant. Whether the country exhibits high levels of voice and democratic accountability—namely protecting civil society space, media freedoms, and civil and political liberties—matters significantly, controlling for other factors. If, among its World Cup peers, a country rated in the top third in the voice and accountability indicator of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), it had a 70 percent chance of advancing to the round of 16, while if it ranked in the bottom third it only had a 30 percent probability of advancing.

Second, we find that home field advantage and the extent of the fan base at the World Cup (number of fans traveling to the Cup to cheer for their national team) also matters, explaining part of the success of teams from North, Central and South America in advancing to the second stage (see Figure 1).

Both determinants of soccer success may be related, reflecting the flip sides of the coin. To an extent, fan support for their national team may be the (bottom-up) counterpart to the (top-down) enabling accountability environment provided by each government. Citizen empowerment and participation does matter in soccer as well, as the free media and fan base passionately encourages their national team, while also holding them accountable.

This ought not shock us, since these determinants extend well beyond soccer; it is what we find matters enormously for development success in general, and in particular in countries seeking to harness their own natural resources for socio-economic progress. Voice and accountability, as well as citizen feedback, is also found to matter for the success of public institutions and NGOs.

It may not be a coincidence, therefore, that countries like Russia, Cameroon, Honduras and Iran went out during the first round, while Costa Rica, Chile, Uruguay, Switzerland and the United States advanced.

Following the games in the second round, the number of teams left shrunk to eight last week, and, with countries like Algeria and Nigeria exiting at that stage, no team with even relatively low standards of democratic governance (i.e., rating in the bottom half of voice and accountability indicator in the WGI) made it to the quarterfinals. Following this weekend’s quarterfinal games, there are four teams left standing in the semifinal games: Brazil vs. Germany and Argentina vs. the Netherlands, each team harboring high hopes to lift the cup next Sunday.

While neither Argentina nor Brazil match the quality of democratic governance of their respective European contenders, both have made significant strides since the military regime days of a generation ago, and now rate in the top half of the voice and democratic accountability governance indicator. And, importantly, both South American teams have a significant “home field” and fan base advantage over Germany and the Netherlands: Brazil is the host, and Argentina, its neighbor, has about 100,000 fans crossing the border to support its team (the second largest contingent of visitors after the United States). Hence, in terms of a likely winner, our statistical results would suggest that both quarterfinals could go either way, since the teams with higher governance standards have the lower fan base.

Obviously, even if governance matters, winning games is not all about democratic governance at the national level, and about passionate “civil society” support in the stadium for a team. Governance also matters at an organizational level, namely the cohesiveness and effectiveness of a team beyond the individual quality of each player, can make a big difference. In fact, in previous writings we have offered one definition of good governance as the ability of a team to be more than the sum of its parts. During this Cup, Costa Rica, Chile, France and the United States illustrated such good governance at the team level, in contrast to Cameroon, Ghana, Italy or Spain, each producing so little in spite of their individual stars. In the South Africa World Cup four years ago, Ghana exemplified good governance as a team, in contrast with France’s team then, which was the polar opposite, and so was the Argentina team, at the time poorly managed by Diego Maradona.

Heads I Win, Tails You Lose

Beyond national governance and civic space, there are luck factors that make a difference. An injury like the Brazilian star Neymar’s (now out of the World Cup) may end up mattering for Brazil’s fate, and, conversely, for Argentina, so might one more of those inspired plays by Leo Messi. Another misstep by a referee can also make the difference.

Luck may determine who wins the Cup in other ways, unrelated to the “luck of the draw” in the first rounds’ group assignments (which we found doesn’t make a difference). Instead, what may still matter is the “luck of the coin toss” in penalty shootouts forced by tied games. A paper by Apesteguia and Palacios-Huerta in the American Economic Review that draws on almost 3,000 penalty kicks over roughly 40 years of major international soccer and points to psychological factors, finds that the team that kicks the first penalty has a 60 percent probability of winning the penalty shootout! No wonder their paper also finds that the team that wins the coin toss always opts to kick first.

And no wonder that, so far during the current World Cup, the chance of the team kicking first during a penalty shootout winning is 66.6 percent. Costa Rica and Brazil—kicking first—won their respective shootouts against Greece and Chile in the round of eight, while the Netherlands won their shootout against Costa Rica in this weekend’s quarterfinals in spite of shooting second (but countered that by opting to substitute their starting goalkeeper with a penalty specialist, who blocked two shots!).

Soccer pundits tend to decry the penalty shootout, claiming that it is tantamount to a lottery. In fact, the above suggests that it is akin to loaded dice instead, where the lottery is actually in the coin toss, which then loads the deck in favor of the team that wins the coin toss.

But there is a fix, also drawn from the paper authors: If the penalty shootout is kept, at least FIFA authorities could organize it like the ordering of the respective serves in tennis tiebreakers. The fair penalty shootout option would be run like this instead: The first penalty is taken by the toss coin winner, then the next two penalties by the other team, then the next two by the coin toss winner, and so on, until 10 penalty kicks are completed. If they are tied at that point, they keep taking two penalties per team, alternating which team kicks first.

Brief Organizational and Policy Implications

These evidence-based insights point to two very different types of recommendations for FIFA. One refers to the rules in settling a game, namely changing how the game tiebreaker is conducted in order to at least ensure that the ‘dice is not loaded’, as per suggestion described above. That should not be unthinkable; after all, following the last World Cup outcry over the goal denied to England against Germany when the ball had clearly crossed the line, FIFA slowly relented and adopted goal line technology—akin to tennis again.

In addition, this work supports the implied message from successful soccer nations to FIFA: Democratic governance matters and so does the fan base of a country. But the odds of FIFA listening to this message are rather slim, because it would mean that the perennial top leadership in this autocratically run organization would have to exit, for starters, allowing for a semblance of democratic transition.

More broadly, we are reminded that just as we have learned that sending billions of dollars in foreign aid, or being rich in natural resources, doesn’t guarantee socio-economic development for a country and benefits to the people, neither oil riches nor money alone can “buy” national soccer success either. What makes the difference is good governance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Explaining Success at the World Cup: Money or Governance?

July 7, 2014