As the United States limps toward another deadline to fund its transportation infrastructure, in June the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee passed a six-year, $275 billion bill, the Developing a Reliable and Innovative Vision for the Economy (DRIVE) Act. While Congress has many questions yet to answer, including how to pay for future projects, the DRIVE Act marks a giant step forward to address the country’s freight needs. In line with our recent proposal, the bill establishes a national freight investment program, geared to regional economic priorities and funded at more than $2 billion each year.

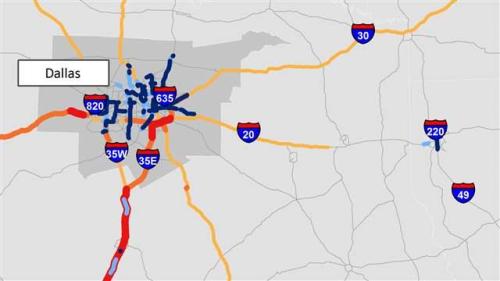

The program cannot come soon enough. Congestion at the country’s biggest ports and in the largest metro areas holds back the efficient exchange of goods nationally, which ripples throughout the infrastructure network and points to the need for more targeted federal freight investments to drive growth.

The DRIVE Act holds promise for several reasons:

- In addition to a national freight strategic plan, the act requires the development of state freight plans. This process can help articulate regional concerns and build a broad inventory of infrastructure assets. Complemented with other pending legislation, such as the Future Transportation Research and Innovation for Prosperity (TRIP) Act, additional improvements in freight data, planning, and policy development can take place nationally.

- The act also provides a more expansive, multimodal approach to qualify transportation facilities for federal support. Laying out a network in three components—a Primary Highway Freight System, Critical Rural Freight Corridors, and Critical Urban Freight Corridors—offers flexibility to prioritize regional freight assets based on intermodal connections, multistate projects, trade gateways, and other criteria. However, a truly multimodal approach outlined within the National Multimodal Freight Policy and Investment Act should still be the end goal.

- Finally, the act boosts freight data investment by at least $10 million per year, an amount that can improve critical public data sources such as the Commodity Flow Survey and the Freight Analysis Framework. The expansion of transportation investment data and planning tools is essential to identifying freight bottlenecks and responding to the infrastructure needs of local producers, consumers, and distributors. Developing more geographically granular metrics and encouraging greater cross-agency collaboration are especially helpful in this respect. Implementing the act in tandem with other legislation, like the recent Port Performance Act, would further improve the country’s data collection efforts.

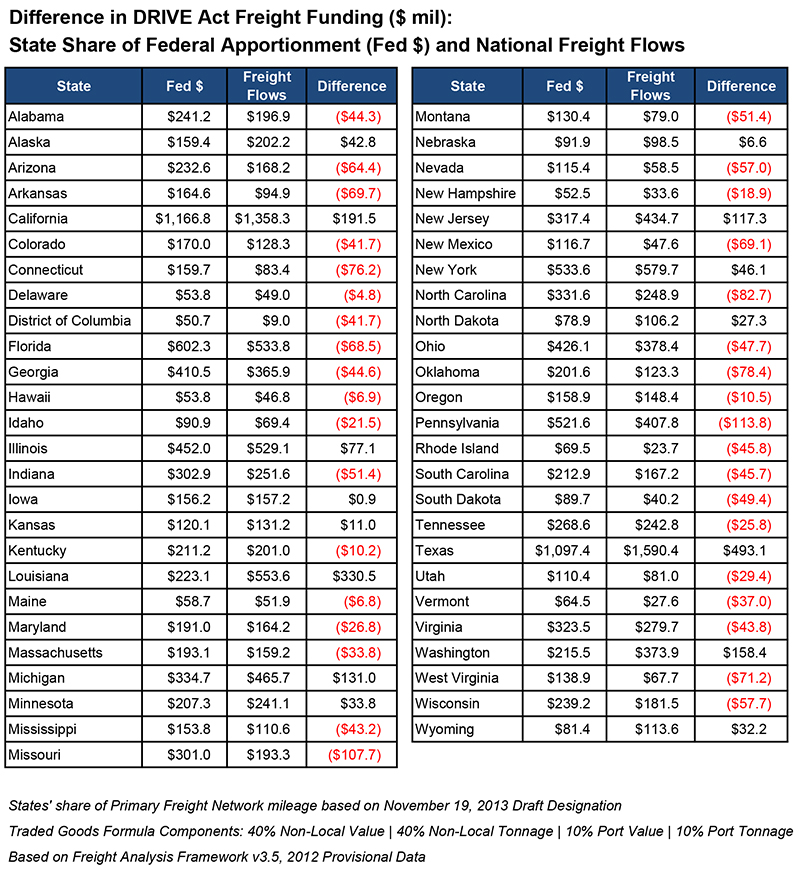

Despite these constructive steps, the DRIVE Act falls short in how it distributes funding to individual states. Although the newly designated national network helps channel funds to a broad range of freight assets at the state and local level, the apportioned amounts fail to connect to more relevant economic- and performance-based criteria. Instead, they follow traditional highway program apportionments. As a result, these formulas would spread money without clear purpose, and many states, like Texas, California, and New Jersey, would receive far fewer dollars relative to the amount of goods they move each year.

As we have previously written, we prefer to see competitive grants as part of a final freight program. Formulas are still a key component—they just need to reflect freight realities. We suggest a system based on the total value (40 percent) and tonnage (40 percent) of goods traded by the states, along with the total value (10 percent) and tonnage (10 percent) moved through their port facilities. This would better target spending in areas with more pronounced needs, a system similar to what appears in the GROW America Act. For instance, Louisiana could go to over $553 million over the DRIVE Act’s six years, and cargo hubs like Michigan could see an additional $131 million over this same span.

The DRIVE Act is a potential cornerstone for federal freight policy, but Congress still has more details to sort out.

Correction: An earlier version of this blog post highlighted freight funding according to a primary freight network (PFN) designation; however, the DRIVE Act would distribute funding to states based on their traditional highway program apportionments. In particular, rather than basing the amount of freight funding states would receive annually in terms of their PFN mileage, this update illustrates the total amount of freight funding they would receive according to traditional apportionments over the DRIVE Act’s six-year duration.

Commentary

The Senate builds a freight policy foundation, but construction ongoing

July 9, 2015