While more Americans are relying on alternative modes to get to work every day, cars still define most commutes. Over time, these high driving rates not only reflect a built environment that continues to promote vehicle usage—despite recent shifts toward city living and job clustering—but also call into question how well our transportation networks offer access to economic opportunity for all workers.

This is especially important for those workers without cars.

The most recent 2013 Census numbers shed additional light on their commuting habits, showing how more than 6.3 million workers don’t have a private vehicle at their home. That’s equal to about 4.5 percent of all workers, compared to 4.2 percent in 2007.

Yet, zero-vehicle workers still do quite a bit of driving. Over 20 percent drive alone to work—meaning they find a private car to borrow—and another 12 percent commute via carpool. Both rates jumped between 2007 and 2013, defying national trends toward less driving. This paints a discouraging picture about transportation access across the country for a segment of commuters who must expend extra effort to simply get to work.

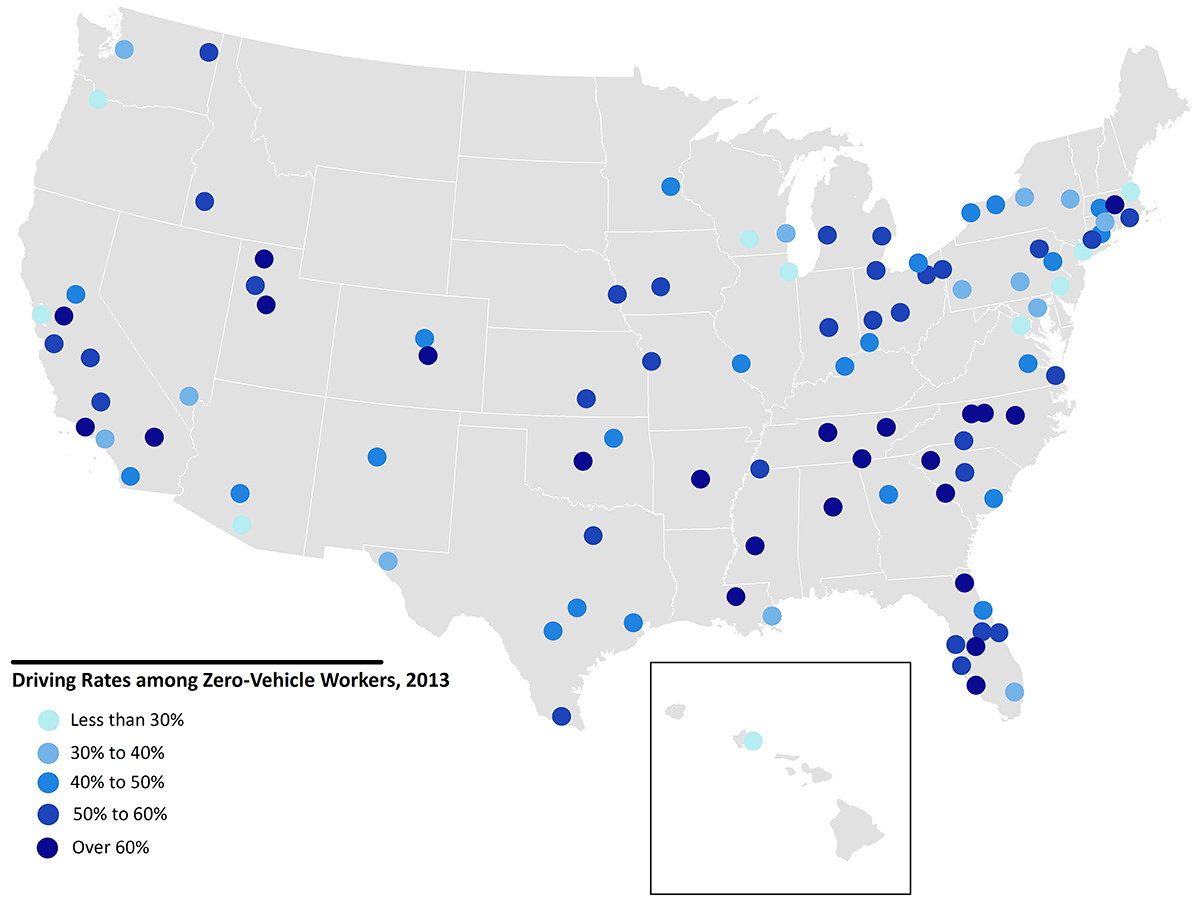

Metropolitan data underscores the breadth of this problem. Transit-rich metros like New York, San Francisco and Chicago are among the areas with the most zero-vehicle workers who drive less frequently. However, other large metro areas like Dallas, Detroit and Riverside see over half of their zero-vehicle workers find a car and drive to work. Driving rates jump to over 70 percent in metros like Birmingham, Ala., Jackson, Miss., and Provo, Utah. Across 77 of the 100 largest metro areas, at least 40 percent of zero-vehicle commuters drive to work.

Metropolitan Share of Zero-Vehicle Commuters Driving to Work, 2013

Source: Brookings analysis of American Community Survey data

These commuting habits confirm prior research. Our work has found that nearly all zero-vehicle households live in neighborhoods with transit service, but those routes only connect them to 40 percent of jobs within 90 minutes. On the flip side, the Urban Institute found vehicle availability can improve economic outcomes for housing voucher recipients, especially in terms of neighborhood choice. Little wonder then that many car-less commuters find a vehicle to get to work.

The big goal for policymakers at all government levels is to improve access to jobs, for all workers and across all transportation modes.

With many workers facing limited job access without cars, it’s clear why the automobile is still the mode of choice. Andrew Owen and David Levinson’s recent automobile and transit models verify it. Maps from MIT’s You Are Here show the car winning on long city commutes; imagine if those maps spread through the whole metro area. But these advantages also push households to take on the added expense of vehicle ownership, an especially large burden for lower-income households.

To address this inequity, we need to shift how we plan transportation investments and urban development. Planners and engineers need to think less about mobility—how fast we move—and more about access—how many destinations we can reach. Grounded in the daily experience of commuters, this perspective can help meet the needs of workers and employers, better tying together regional economies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Cars Remain King and Barrier to Economic Opportunity

October 23, 2014