Communities impacted by the 7.8 magnitude earthquake (and subsequent aftershocks) that struck Nepal on April 25th have a variety of needs, stemming from immediate protection of physical safety and security, access to life saving services, and basic subsistence (food, clean water, shelter) and psycho-social support in the aftermath of an extremely traumatic event. In the case of Nepal and the city of Kathmandu, recent reports suggest that the capital city’s critical infrastructure and services were not sufficiently resilient to protect against an earthquake, that the topography of the region is such that landslides remain a concern, and that socio-cultural factors like caste-based discrimination makes some communities more vulnerable than others.

The scope of the natural disaster

According to the April 30 Situation Report of the UN Office of Coordination for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), search and rescue and aid agencies responding to the crisis in the coming days are focused on providing shelter to the displaced–government reports suggest over 130,000 homes were destroyed and 85,000 partially damaged. In Kathmandu alone there are an estimated 24,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) registered in tented settlements, although many more are likely seeking refuge in informal settlements and in the rubble of partially damaged—and still vulnerable—homes. Identifying missing persons, and effectively and ethically managing dead bodies are still a major part of the response. Tents and food are among the highest prioritized areas of need (over 3 million are in need of food aid in the region), and health remains a primary concern as hospitals near the capital have reportedly run out of supplies.

Effective information management—the collection, analysis, and sharing of accurate, timely, and actionable intelligence—is thus a critical part of the response effort, especially as badly affected areas of interest (AOI) are inaccessible physically (due to blocked roads or elevation) or digitally (due to power outages and low bandwidth for communications). Assessment data about infrastructure damage, locations and resources of health care facilities, camps, NGO field offices, and the needs of vulnerable communities are useful to a variety of actors trying to solve a variety of different problems, such as, finding missing family members or determining accessible land routes for effective supply chain management for the distribution of food aid.

Luckily, access to information communication technologies (ICTs) such as the Internet, social media, mobile communications, and commercial remote sensing offers up cost efficient, rapid, and innovative ways to capture and analyze the growing and varied data exploding out of Nepal.

Bigger, Faster, Stronger, Different…now what?

Digital Globe and Google’s Skybox have offered up satellite imagery to the humanitarian community, free of charge so that platforms like Tomnod and Humanitarian Open Street Map (HOT) can harness the power of the crowd (literally thousands of online volunteers) to detect damage to homes, roads, and municipal buildings. UAViators (a volunteer network of professional and civilian UAV pilots spearheaded by QCRI) facilitate information sharing in humanitarian contexts by collecting and sharing enormous amounts of hi resolution fly over video streams with their drones. Artificial Intelligence for Disaster Response (AIDR), for example, is being used to process and filter the hundreds of thousands of Tweets pertaining to hashtags #NepalEarthquake and #NepalEarthquareResponse, so that organizations like Micro Mappers can assess damage in photos with the click of a mouse. The Standby Task Force has been activated to support information management and geo-spatial mapping of information resources for responders—they have prioritized and contributed valuable intelligence on urgent needs, photo and image collection, affected areas, camp information, and offers of assistance, according to their website. Much of this information is then uploaded to data dashboards, like Humanitarian Digital Exchange (HDX). Facebook and Google have both launched Safety Check and Person Finder apps to locate lost loved ones.

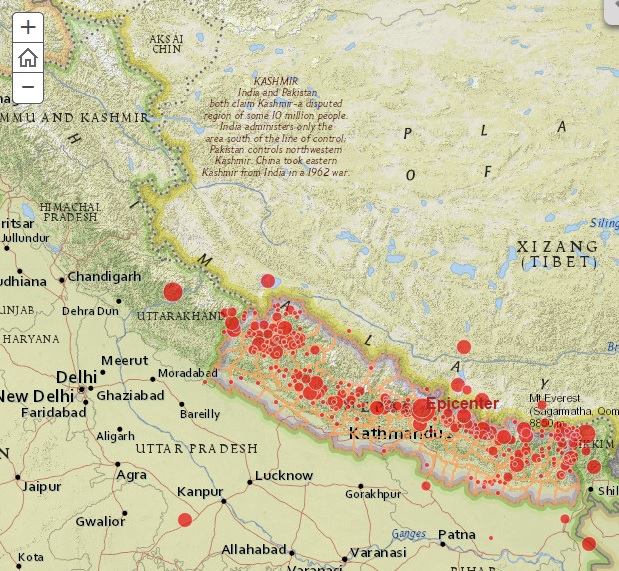

Nepal Earthquake Map

Source: ESRI

While these tools and efforts have indeed increased the potential for more temporal-spatial and category specific situational awareness, the increase in volume, velocity, and variety of data available to responders has also led to an “innovation-action gap,” as a multitude of humanitarian actors still find it difficult to integrate and standardize efforts to collect, verify, and share knowledge for real-time decision making in a variety of complex crises situations.

Deploying hundreds of trusted volunteers to crowd-source and micro-task imagery analysis, for example, allows incredible volumes of data to be processed at warp speeds. But training and difficulty accessing operational platforms remain roadblocks for achieving accurate, reliable results (triangulation is used and is increasingly effective, but there are still challenges) and to communicate effectively. Many volunteer networks use Skype to communicate, making it difficult to monitor chatrooms over time and to identify and respond to requests, or to share geospatial data. UAviators have deployed a range of drones to survey urban and rural areas that are otherwise inaccessible. But there exist a host of coordination, communication, and data upload challenges for the volunteer pilots (although solutions exist for these issues).

Additionally, there are a range of problems and gaps that are noticeable with regard to information outputs stemming from the V&TC community. This involves the multiple forms that data are taking (visual in the form of interactive maps, but also PDF files, sit reps, spreadsheets) and the level of analysis of each (some are in raw form, others have been verified, processed and made actionable for decision makers). Figuring out if and how aid organizations are using these information exchanges is impossible to quantify at the moment.

Mapping the mappers

This is why I’ve put together a team of software engineers, aeronautics researchers, geo-spatial intelligence experts, epidemiologists and public health practitioners, disaster responders, and public policy specialists to try to make sense of the information mess that’s coming out of Nepal.

By engaging in participatory research with a variety of crisis mapping applications and organizations; researching and cataloguing a multitude of publically available, open-source data exchange platforms; and investigating the use of a variety of information management products by a range of decision-makers (local communities, NGOs and first responders, coordinating bodies and host country governments), we are proposing to build a model for identifying capability gaps resulting from divergent information/data streams. This way, we might develop a prototype (a nexus of map layers, a repository or information) for new meta-information management technology. Such a prototype would be a data fusion tool, so that end users (communities, local and international NGOs, governments, coordinating bodies, donors), having unique problems, might navigate lean pathways to access a wealth of rich information (in multiple forms, for example low res for the field, high-res for HQ) currently existing in multiple locations.

Such an investigation may lead to the innovative (and evidence-based) design of a fully functional, near-real time, inter-operable data dashboard for multiple users and stakeholders, linking traditional decision-makers (NGOs, IOs, host-country governments, and affected communities themselves) with the digital humanitarian communities that produce and analyze such data. We hope.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Saving Nepal: the information revolution

May 1, 2015