This piece is the first in a series of blog posts on Isabel Sawhill’s new book

Generation Unbound: Drifting into Sex and Parenthood without Marriage

. Over the course of the next two weeks, we will be hearing from Sawhill and series of scholars in the field about the future of family formation in the United States.

Families in America look very different now than they did just fifty years ago. New opportunities for women, declining economic prospects for men, greater access to contraception and abortion, and changing social norms have transformed the family.

Complex and changing American families

Though most young Americans say they hope to marry someday, their behavior tells a different story. The proportion of Americans who are married has dropped from 72 percent in 1960 to 51 percent in 2010. Part of this is because men and women are marrying later – and this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Marrying at a later age is associated with better and longer lasting marriages. One reason that people are delaying marriage is because more Americans (particularly women) are getting post-secondary degrees.

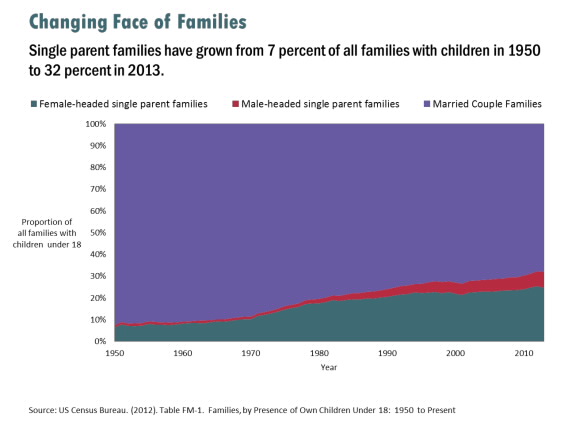

Despite forgoing marriage, young Americans are not forgoing parenthood. Births outside marriage are the main driver behind the growth of single parent families in America (shown below) and represent just over 40 percent of all births (and over 50 percent for women under the age of 30).

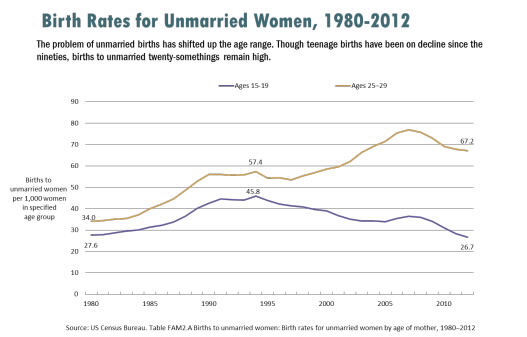

Though we’ve made great strides in reducing births to teens (most of which are outside marriage), the problem of unwed births has moved up the age scale. Birth rates for older singles have dipped as a result of the Great Recession, but they could easily resume their upward trend once the economy improves.

Births to unmarried women are largely unplanned. Approximately half of all pregnancies in the United States are reported by the mother as unintended, and that number increases to 70 percent among single women under thirty. Why should the economy have any impact if most of these pregnancies and births are unplanned? Perhaps people are more cautious when times are tough. As we will discuss in a later post, we need something better than a soft economy to turn this situation around.

A growing class divide in family formation

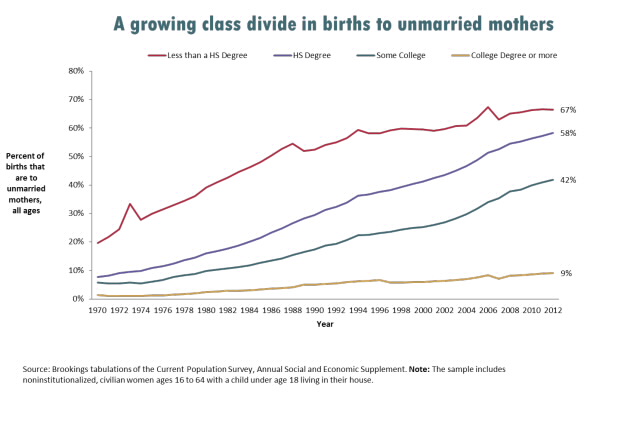

The rise in unwed childbearing is particularly troublesome because it is heavily concentrated among those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Less than ten percent of births to college educated mothers occur out of wedlock whereas almost sixty percent of births to women with only a high school degree occur out of wedlock. It is not as if less advantaged women want to have these births. Quite the contrary. Unintended birthrates for young unmarried women living below the poverty line are more than six times as high as unintended birth rates for more well-off young unmarried women.

Drifting into parenthood and future disadvantage

Generation Unbound describes two types of young Americans: planners and drifters. (Of course, we are all a little of both.) Planners are waiting to marry and having kids within marriage. Drifters are having children early and outside of marriage. They are often cohabiting when the baby is born but about half of them split before the child is five years old. This kind of instability cannot be good for children and research from the Fragile Families project suggests it is not. Combined with growing gaps in income and in education, this widening divide in family structure threatens social mobility for the next generation. In subsequent posts we will say more about what might be done to reverse these trends and improve children’s prospects.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Families Adrift: Is Unwed Childbearing the New Norm?

October 13, 2014