What would happen if teen mothers waited a few years to have children? What if they simply got their high school diploma? What if they did both? These are three of the “what-if” scenarios considered in a recent Child Trends research brief, co-authored by our own Isabel Sawhill.

Teen parenthood’s intergenerational cycle of disadvantage

Being a teen mother is not easy. Not only are they more likely to be poor and to rely on public assistance programs to make ends meet, but they are also more likely to have children who struggle as adults themselves. Breaking this cycle is important, but no one-size-fits-all solution has emerged—partially because it is difficult to evaluate the intergenerational damage of teen pregnancy, never mind to evaluate the efficacy of any teen pregnancy intervention. To avoid these obstacles, the authors use the Social Genome Model, a life-cycle micro-simulation model developed at Brookings and based at the Urban Institute, to estimate the effects of teen pregnancy interventions on the life outcomes of teen mothers’ children.

Improving teen mothers’ lives to improve their children’s lives

It has been suggested that two important steps to reaching the middle class are delaying childbearing and getting additional education. The authors of the Child Trends piece have focused their simulations on these two steps, testing the effect of:

- Delaying maternal age at first birth by two years

- Delaying maternal age at first birth by five years

- Assigning the teen mother a high school diploma, keeping her age at first birth constant

- Delaying maternal age at first birth by two years and assigning her a high school diploma

Both delaying birth and increasing maternal education bode well for the children of teen mothers. They enjoy higher family incomes; they are less likely to be parents by age 29; and they report being in better health. While the authors find that receiving a high school diploma has the largest effect, they note that longer childbearing delays result in larger, more positive effects on children’s outcomes.

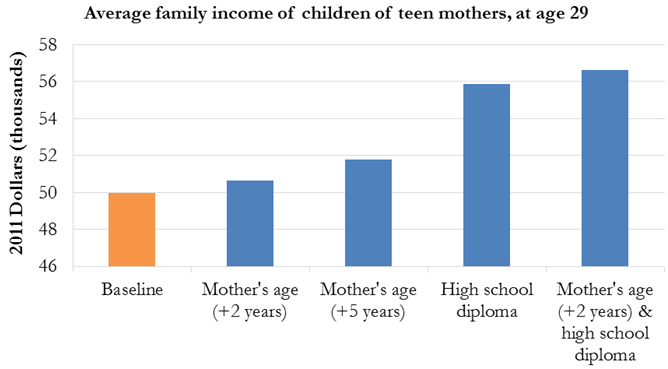

Shown below are average family incomes of teen mothers’ children under each intervention scenario compared to a baseline, i.e., keeping everything as it stands now.

Whereas children of teen mothers without a high school diploma have family incomes of around $50,000 by age 29, their counterparts with mothers who delay their first birth by just two years and receive a high school diploma have incomes that are nearly $6,600 higher.

What next?

We know that the circumstances into which children are born are crucial in determining their opportunities later in life. The age and education of a parent can drastically affect any number of these circumstances, including family income and parenting quality. The Child Trends brief provides empirical support to the claim that there are societal gains to be had by modestly delaying birth and increasing maternal education. However, whether their “what-if” simulations are feasible in the real world remains to be seen. As the authors themselves admit, their findings only, “suggest what could be accomplished.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Teen Moms: The Difference Two Years and a Diploma Make

August 18, 2014