This is shaping up to be the decade of protest. From Chile and Brazil to Turkey, Thailand, and Venezuela, riots have broken out and even – as in Ukraine – broken governments. Each protest has its own character, of course: but there are striking similarities among them – and, in particular, among the people participating in them.

The Protestors Are Pessimistic, Not Poor

For one thing, the protests are being led by relatively wealthy people in relatively wealthy countries. The “prototypical” protestor is not a nothing-to-lose risk taker, but middle-aged, middle income, and more educated than the average, falling into the outdated category of “middle class”. He or she has, for the most part, made significant investments in the socio-economic system that she lives in, and yet is pessimistic about opportunities for the future within it. In fact, the protestors look a lot like the upwardly mobile but unhappy “frustrated achievers” around the world we have been tracking for years.

A Story of Seven Protests

- In Chile, protests were driven by university students unhappy about fees

- In Brazil, middle class folk were upset about the precarious public health system and rising fuel costs.

- In the Arab Spring countries, the protesters were frustrated with the lack of democracy and future opportunities.

- In Russia, middle class people protested the lack of transparency in governance.

- In Turkey, generalized frustration with corruption involves relatively educated and wealthy people.

- In Venezuela, middle class folk are fed up with “Chavismo” and the unstable future it portends.

- Finally, the dramatic recent trends in Ukraine were sparked by the government’s choice to move closer to the East rather than to Europe, and the future that signified.

Well-being and Protest

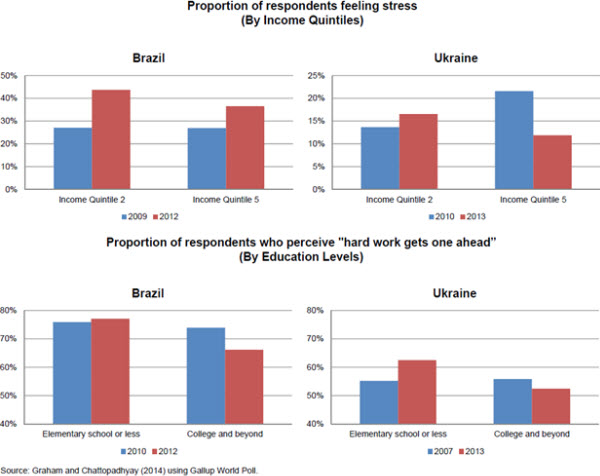

From our analysis of the Gallup World Poll, and using the metrics provided by the new “science” of well-being, we can see that the cohorts most likely to be participating in the Arab Spring protests had average income, education, and life satisfaction levels, but had very pessimistic assessments of their future well-being. In Brazil, stress has been increasing in recent years for all respondents, but the most for those in the middle income quintiles and for those in the 25-45 age range. We also find that those with college education are much less likely to believe that hard work gets you ahead. Thailand and Ukraine exhibit the same pattern consistently: the most educated are less likely to believe in success through hard work, and stress levels are the highest in the middle income and middle age cohorts.

The New Global Challenge: Frustration With Lack of Mobility

The global community has made great strides in reducing absolute poverty in the past two decades. But many countries now house an increasingly frustrated middle class (frustration which many U.S. citizens also share). Left unaddressed, festering public resentment can create as much economic and political turmoil as mismanaged macroeconomic policies can do – including in countries which are performing well economically. A paradox of progress, perhaps: but one that has to be addressed.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Decade of Public Protest and Frustration with Lack of Social Mobility

March 7, 2014