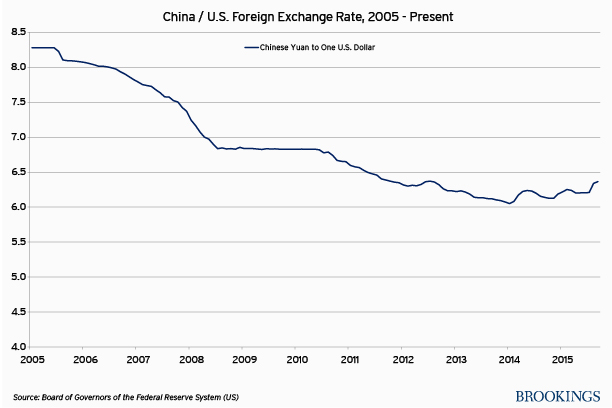

When President Xi Jinping and an entourage of Chinese officials come to Washington this week, one of the top issues on the economic agenda will once again be the exchange rate. China’s exchange rate was under-valued for a long time, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and academic economists. But in recent years, China has largely corrected this. The yuan has appreciated about 25 percent against the dollar and even more against its average trading partner.

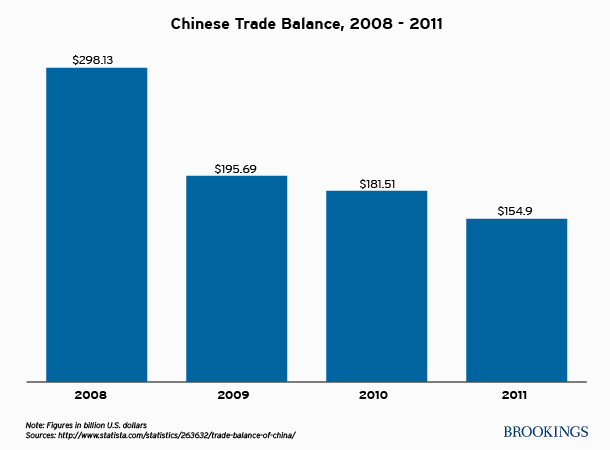

Between 2008 and 2011, China’s trade surplus declined by nearly half from $298 billion to $155 billion. The IMF has now declared the currency “fairly valued,” and as of a few months ago, it was not much of an issue between the United States and China.

But then in August, China devalued its currency and that set off a market sell-off around the world that wiped out trillions of dollars of value from global stock markets. To be fair, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) was trying to change the system for the daily fixing to make it more market-oriented and to respond to IMF critiques. But the move was combined with a so-called “one-off devaluation” of 1.9 percent. The move came right after disappointing export numbers and without much explanation. Chinese officials were surprised that the small move set off such powerful expectations of major currency devaluation. Ever since, the authorities have been in a battle to stabilize the currency at a rate of about 6.4 yuan to the dollar. It is ironic that after years of keeping the currency low, China is intervening now to keep its currency high.

PBOC is right to think that there is no basis for a significant devaluation. After several years of decline, China’s trade surplus is starting to increase again. This year, the real growth of China’s exports is slow, in line with world trade. There is some decline in China’s export prices, so the headline monthly figures sound bad—exports down 8.3 percent in July and 5.5 percent in August. But China is holding its share of global trade, so there is no evidence of declining competitiveness. Meanwhile, China’s import prices for energy and minerals have dropped sharply, and import volumes are down as well because imports are primarily used for investment, which is slowing. As a result, China will have its largest ever trade surplus this year. Through August, the surplus was $367 billion, compared to $200 billion in the same period last year.

In search of stability

Despite this large trade surplus, which would argue for further yuan appreciation, the small devaluation has raised the possibility of further devaluation, and this is spurring already large capital outflows from China to new heights. China spent $94 billion in reserves defending its currency in August, and reserves are down about $400 billion from their peak a year ago. It is unusual to have downward pressure on a currency with such a large trade surplus, and it reflects capital outflows even larger than the surplus. Some of this is Chinese savings that can no longer be invested productively at home. But some is no doubt speculative flows betting on a devaluation.

With its large reserve pile and sound fundamentals, China may be able to convince the speculators that there will be no significant devaluation. But it is also possible that the speculative flows will accelerate and that after a few months the central bank will have to give up defending the currency. A disorderly devaluation would be a bad scenario for the world economy and for U.S.-China relations. Many emerging markets have to devalue their currencies because their export earnings have dropped so much. So China can anticipate that many currencies will need to stay out ahead of China in terms of devaluation.

There is really not much the United States can do in this situation, except encourage the Chinese to continue to try to change the negative sentiment among investors by stabilizing the currency and by accelerating reform. China still has a lot of restrictions on inflows of capital, both portfolio investment in its capital markets and direct investment in most of the modern service sectors (finance, telecom, healthcare, logistics, and others). In dealing with its exchange market pressures and with the negative narrative that has developed about China’s prospects, it would help a lot if China would open up these protected sectors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Currency devaluation and U.S.-China relations

September 21, 2015