If the recent United Nations projections turn out to be correct, the world’s population will continue to grow at a relatively high pace throughout this century, and many of you will still be alive when we reach the 10 billion mark in 2060. If you want to know the precise odds that you may still be around to see this, you can check them at www.population.io.

Why is population growth happening now and why so rapidly? Contrary to common wisdom, rapid population growth is the result of development, not of misery. It is driven largely by the fact that people live longer, and longer lives mean more people, even with fewer children per family. In fact, the number of children (age 0-14) has hardly increased since 2000 and is expected to remain at around two billion throughout most of this century. In other words, all of today’s global population growth comes from higher numbers of adults.

Population growth has been reshaping our world, which is fundamentally different today than when our parents were our age. In the span of 100 years (between 1950 and 2050), the world’s population will have nearly quadrupled (from 2.5 billion to around 9.5 billion). This dramatic acceleration can be seen in the demographic profile of our planet: today 92 percent of all humans were born after 1949 and some 70 percent of those alive today are still expected to be living in 2050.

Demography is one of the most accurate social sciences. This is because the people that will occupy our planet in the future are already alive today, and the drivers of future population growth are well known: economic development, urbanization, health, and education. Still, a major debate has been unfolding about the rate of population growth and the possibility that we may even reach a global peak in this century. The two protagonists in this debate are the U.N.’s Population division and the Austria-based International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), with which one of the authors of this blog is associated. IIASA claims that population growth will slow down even faster than anticipated, and that the world’s population will peak at 9.5 billion people (in 2070) before declining to below 9 billion by the turn of the century. This may seem like a very academic debate, but the difference between the U.N. and IIASA projections is huge: 2.3 billion people, almost equivalent to India and China combined!

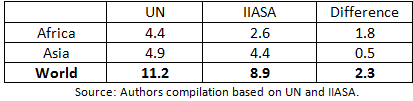

What is the source of this enormous gap, which would have dramatic implications, particularly in the poorest areas of the globe? Geographically, most of the discrepancy in the projections relates to Africa, where in any scenario, the bulk of future population growth is expected to take place. The U.N. anticipates that Africa will be home to some 4.4 billion people by 2100, more than four times as many as today! By contrast, IIASA predicts a much more modest increase to 2.6 billion people. In Asia, there is also a gap of half a billion people between the projections. The U.N. predicts 4.9 billion by 2100, while IIASA estimates 4.4 billion (see table). For the rest of the world, the gap in projections is similar.

Table 1: A world of 10 billion? World population projections until 2100 (in billions)

The underlying reason for these major discrepancies is different assumptions about future fertility, especially in Africa. Keep in mind that these are projections over the long run (until 2100), such that small differences add up to big numbers: One additional child today, with much better odds to survive into adulthood, means an additional mother or father in the future, who then in turn produces more children.

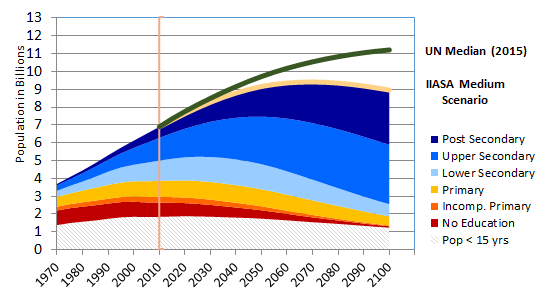

The U.N. broadly extends the current patterns of fertility into the future and only expects a decline from the current 4.7 children per family in Africa to 3.1 children by mid-century. By contrast, the IIASA projects a much sharper drop, driven by the global expansion of education. Let’s look at Kenya, which the U.N. projects to be a country of about 160 million by the end of this century. Today, the average Kenyan family has 4.5 children, in line with the African average. However, while a woman with no education can expect to have six or seven children, that number drops to three in households where the mother benefited from secondary education. By 2050, it is expected that more than 95 percent of Kenyan future mothers will have completed at least lower secondary education. If you include the power of education in demographic modelling on top of the general decline in fertility across all groups in society, Kenya’s future population will “only” reach 100 million by 2100 (IIASA projection), 60 percent lower than the U.N. forecast. This means that if you apply the same method to the whole world, we might indeed not reach 10 billion (see figure).

Figure 1: How the expansion of education can slow down population growth

Source: Authors compilation based on United Nations Population Division 2015 revision and Wittgenstein Center/International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis 2014

And if there was one takeaway for policy it may well be that the future of the world’s sustainable development lays in the path that girls, particularly in Africa, are allowed to take to school on any single day.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Will the world reach 10 billion people?

September 4, 2015