On February 12, the Center for Universal Education at Brookings launched the Arab World Learning Barometer, a new report and online interactive that show how the challenges in providing good-quality education in the Middle East and North Africa threaten to undermine the region’s economic growth and political stability. Expert panelists discussed the links between education and employment, with a special focus on the region’s youth bulge and its particular implications. Get full event audio and video here. A recap of the opening portion of the event appears below.

CUE Fellow Liesbet Steer opened the discussion with a review of the Barometer, noting first the progress in getting children into school but also three ways in which we need to expand our attention. She said that we need to:

- “start focusing more on those that are children being left behind, the disadvantaged groups.”

- “pay a lot more attention to the quality of education and what kids are actually learning when they are in school.”

- “look at secondary and post-secondary education to complement what’s been going on in primary, and especially relevant to today what kind of skills are children getting while in school that prepare them for the labor market.”

Steer noted two important facts about the Arab World Learning Barometer: the scarcity of data in some countries and the variety of countries in the region in terms of their socio-economic background. Of the 20 countries examined, she said, only 13 have some kind of international learning assessment at either the primary or secondary education level, and only seven have assessments at both levels. The range of socio-economic experience goes from Yemen’s $1,000 per capita income to Qatar’s $80,000.

Steer noted two important facts about the Arab World Learning Barometer: the scarcity of data in some countries and the variety of countries in the region in terms of their socio-economic background. Of the 20 countries examined, she said, only 13 have some kind of international learning assessment at either the primary or secondary education level, and only seven have assessments at both levels. The range of socio-economic experience goes from Yemen’s $1,000 per capita income to Qatar’s $80,000.

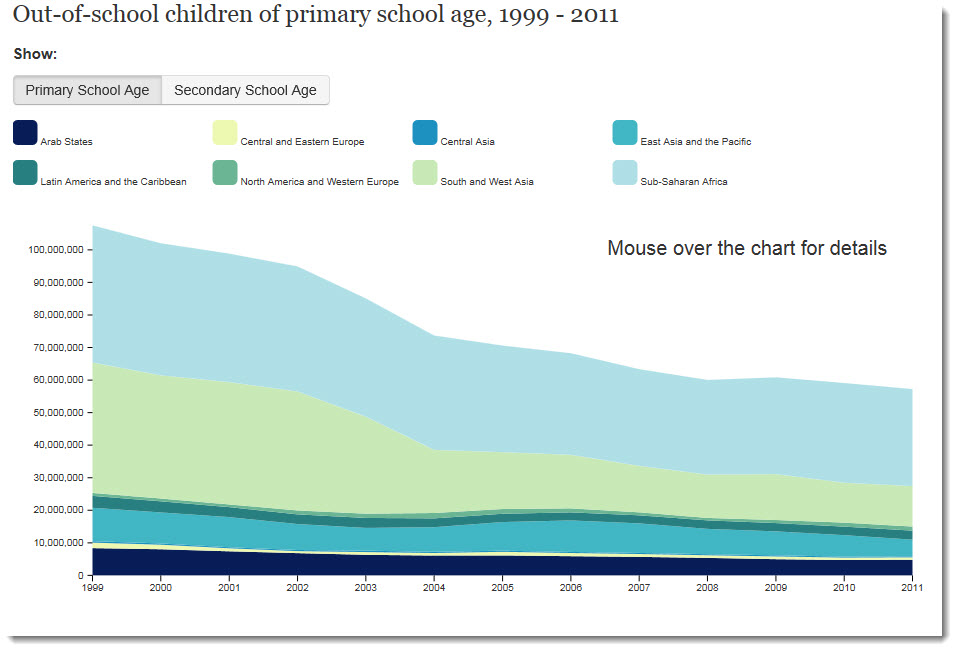

The good news, Steer said, is that “children are getting into school” and “over 90 percent are completing their primary education.” But like the diversity of income, enrollment ranges throughout the region, from 40 percent (secondary school enrollment) in Yemen to 95 percent in Oman.

“Forty-five percent of poor rural women in Egypt have less than 2 years of education compared to only 1 percent of rich urban men.”

One of the chief worries, Steer pointed out, is apparent in the combination of income and location disparities with gender disparities. She called the picture “grim”.

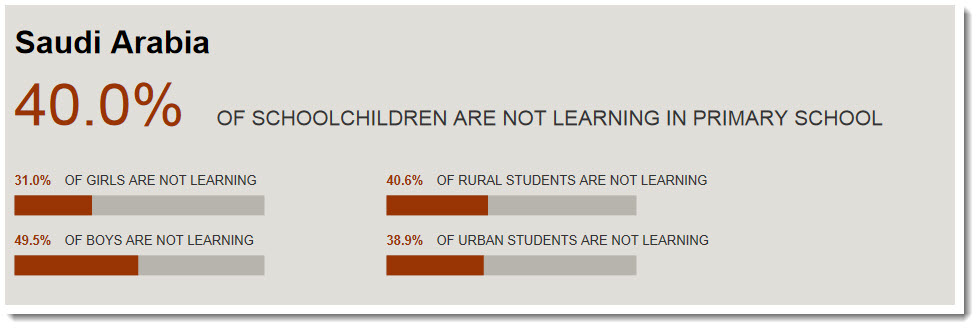

Additionally, “when we look at learning,” she said, “the news unfortunately is pretty bad across the board.”

More than half of primary age children are not reaching basic learning benchmarks. And just under half of secondary age children. Now what does this mean? At primary age, this actually means that children after four years of schooling are not able to read a sentence nor are they able to add up or subtract whole numbers, something you would expect they would be able to do.

Finally, Steer noted the problem of employment opportunities for youth in the region.

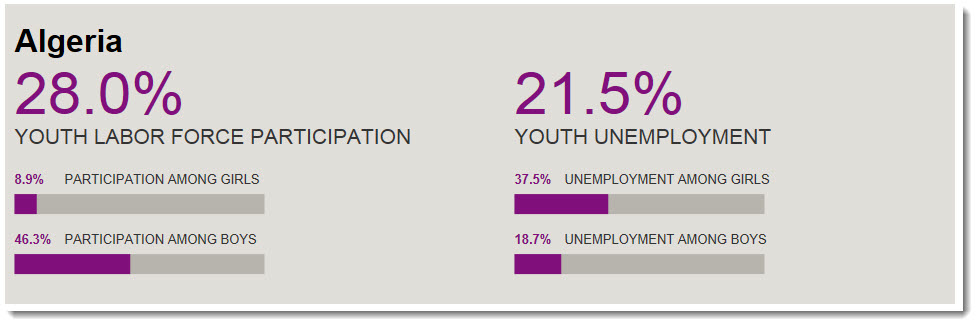

There is a strong connection between learning and employment opportunities. Forty percent of employers in the Arab world cite skills shortage as a serious constraint. The Arab world competitiveness reports ranks education as one of the most significant constraints to economic growth. Youth are dropping out of the labor market or even if they enter it they are not able to find jobs. Youth unemployment is between 20 and 30 percent in most of the countries.

And gender disparities, too, are present in labor force participation:

Once they are in school, interestingly girls seem to be doing slightly better. They are transitioning from primary to secondary at a higher rate than boys, they are also consistently also learning more. So that’s an interesting fact that’s happening in the school system. Now, when they leave unfortunately, here is where the picture changes again. Women are doing worse than men. In Tunisia labor force participation rate is only 20 percent for girls, it’s more than 40 percent for boys. The youth unemployment rate is 35 percent for girls and only 27 for boys. So this is something that we certainly also found quite striking when we looked at the data.

Steer highlighted five areas to explore to address this learning crisis: access to early childhood education, engaging the private sector, obtaining better data, teachers, and the challenges of conflict, particularly Syria.

Report co-author Hafez Ghanem, a Brookings senior fellow, addressed the issues of resources and curriculum. “It does not seem to be a problem of resources,” he said. “If nearly half the children in Qatar are not learning, it cannot be because Qatar is a poor country; it has one of the highest GDP per capita in the world.”

As one possible explanation, Ghanem pointed to the demand side for education:

In some of the countries, maybe education is not seen as particularly important or necessary. If, as a younger Qatari, you are sure that whether you learn or you don’t learn you are going to get a good job in government … your starting salary is more than $100K a year … then why learn?

But Ghanem drew a distinction between countries in the region, particularly the Gulf states and the rest. In Tunisia or Morocco, he observed, “People value learning and they don’t have the kind of resources that some people in the Gulf countries have. They need to be competitive, they need to find a job, and therefore they put a lot of weight on learning and going to school.”

“I think in the Gulf countries there might be an issue on the demand side, that people might not feel that education is particularly important. But in the rest of the Arab world I think it is more of a problem on the delivery side, on the quality of the curriculum, and how this curriculum is being taught.”

From there, Ghanem described the problems of curriculum content and curriculum delivery. “One of the observations I received from talking to private sector in the region,” he said, “is that students in the region do not learn what we call twenty-first-century skills like working in teams, problem solving, being innovative, risk taking. So, there is a problem with the curriculum that is too traditional, that is too much based on rote learning, learning things by heart.”

Further, he said, “whatever the curriculum is, it is not delivered in an effective way.”

We see a lot of problems in terms of the quality of teachers, in terms of the numbers of teachers. Even when we have good teachers, and the right numbers, we see a huge problem. In Yemen for example we were looking at the numbers for teacher absentees. There are teachers and they are good but they don’t go to school. So it’s as if they are not there. The parents are not involved, communities are not involved in the teaching process. So this is my hunch about why we are getting those rather discouraging results.

The panelists included Perihan Abou Zaid, co-founder and former CEO of Qabila Media Productions; Magdi Amin, principal economist at the International Finance Corporation; and Shantayanan Devarajan, chief economist, Middle East and North Africa, The World Bank.

Zaid, an Egyptian entrepreneur who started selling personalized bracelets in her 8th grade class, pointed to some aspects of the educational system that discourage analytical thinking, leadership, and teamwork.

There is nothing in the education system that will encourage analytical thinking. It’s in fact frowned upon to do so, to question your teacher, to question your parents … while that’s something that encourages creativity. There is no practice of teamwork, not even in sports. … That is something that we don’t encourage. There is nothing unless you are in private school or maybe an international school, there is no practice of teamwork whatsoever. And obviously there is no practice of leadership. Because there are no student clubs there are no leadership opportunities …

So all those things all together, they add to the deficiency in the textbook education or curriculum. And I think those are the skills that are very much needed to create a strong society that can survive different challenges like what we’re facing right now.

She also said that in Egypt, “we never learn to communicate … so now when you disagree with someone he’s automatically your enemy.” It “all starts from school,” she said.

Magdi Amin reviewed the history of centralization in the region from Ottoman times to the current regimes plus the lack of transparency. “In order to move forward,” he said, “the private sector needs to be in a position to play a role in defining not necessarily the quantity but the quality of what gets taught.”

On transparency, Amin noted that many teachers “are not showing up because they are getting paid on the side to do private tutoring and those standards for entering the profession are also for sale.” He continued:

On transparency, Amin noted that many teachers “are not showing up because they are getting paid on the side to do private tutoring and those standards for entering the profession are also for sale.” He continued:

The system was credentialist and not outcome-based. There’s a lack of transparency where the institutions that are performing better aren’t being rewarded. So we need to move to a system where the state is enforcing the right standards but in a more competitive environment where different types of delivery can meet needs are … by end users and they have tools like the Barometer for understanding who is performing and who is not performing so resources can flow to the better performing systems.

Finally, Shantayanan Devarajan addressed the problem of accountability. Despite the “huge demand for quality” education in the Arab world, he said, as evidenced by the fact that students and parents are demanding it, “The system has been designed to not be accountable to those parents, to those students.”

The teachers are paid whether or not they show up for work. And they are not fired easily because you have got very powerful teachers’ unions, you have got very powerful government administrators who are defending them and find them politically valuable. And they are able to block any attempt at reform including contestability … So that is a sign to me that these people are earning some huge rents and don’t want those rents to be dissipated by the possibility that these children will get a good education.

Get full

video and audio of the event here

, and access the

Arab World Learning Barometer here

.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Experts See Grim Picture in State of Arab World Education

February 12, 2014