Editor’s Note: The U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit blog series is a collection of posts discussing efforts to strengthen ties between the United States and Africa ahead of the first continent-wide summit. On August 4, Brookings will host “The Game Has Changed: The New Landscape for Innovation and Business in Africa,” at which these themes and more will be explored by prominent experts. Click here to register for the event.

With the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit taking place on August 4, now is a good time to reexamine the storyline around Africa. The continent has made progress in economic and social development well beyond expectations, but still has obstacles to overcome. It is time we approach the Africa narrative with enthusiasm, maybe cautious enthusiasm, but enthusiasm nonetheless.

Poverty and Development: The Pessimist’s Narrative

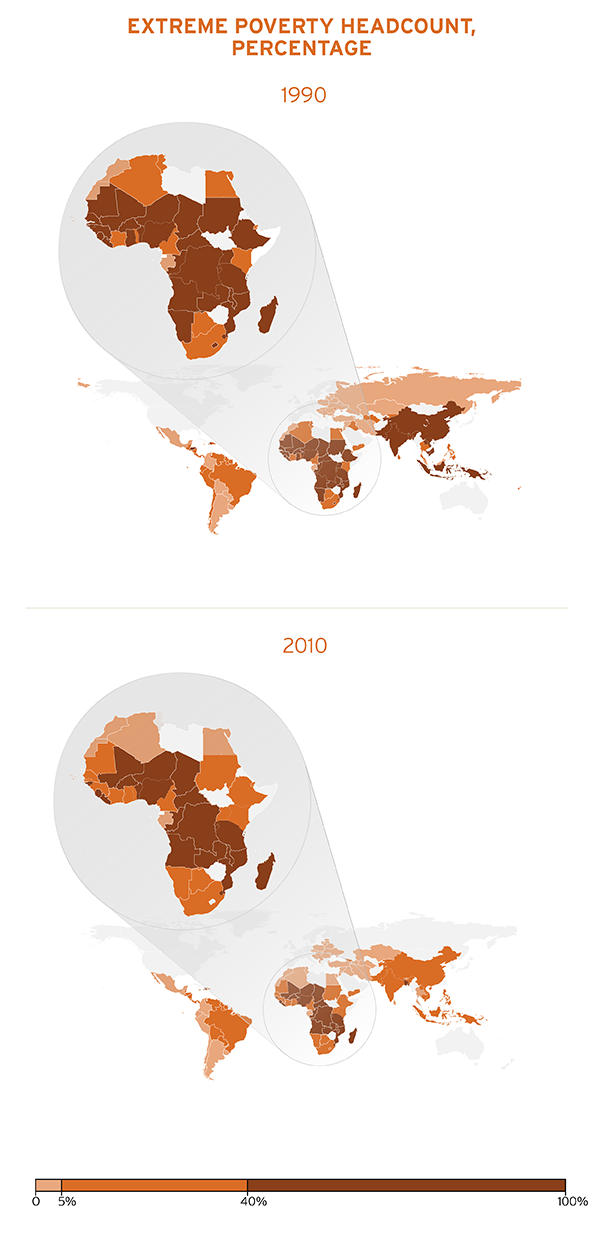

The two maps below reveal the story of the locus of extreme poverty shifting in a generation (1990 – 2010) from Asia and Africa to principally Africa. While there remain millions of people in Asia living in extreme poverty, the vast number of countries with extreme poverty affecting over 40 percent of the population are in Africa.

These maps reflect disturbing statistics. Africa is home to over 400 million people living in extreme poverty and three-quarters of the world’s poorest countries. One African in three is malnourished and over 500 million suffer from waterborne diseases. Twenty-four million Africans, nearly 70 percent of the global burden, are afflicted with HIV. Thirty million (one in four) primary-school-age African children and 20 million adolescents, are not in school.

According to the 2014 Fragile States Index the five countries in the highest category of fragility are all in Africa (South Sudan, Somalia, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan), and 10 of the 16 in the top-two most fragile categories are in Africa.

Turning the Page on the Past

But that is only part of the story. It would be easy to focus on these statistics and see Africa as hopeless, as has been all too common. But a more holistic picture reveals trends that are cause for considerable optimism. That picture is drawn by the maps presenting the level of absolute poverty in countries in Africa over the same period.

What is striking is that the space representing poverty above 40 percent has shrunk, from 31 countries in 1990 to 22 countries in 2010. Delving deeper reveals a host of encouraging data.

Seventeen countries in Africa, accounting for over 40 percent of the population of the continent, have experienced a level of economic growth over 3 percent per capita since 1996. From 2000 to 2010, six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies were in Africa. Africa was the fastest-growing continent at 5.6 percent in 2013, and that momentum is expected to be sustained this year.

The poverty rate in Africa, estimated at 56.5 percent in 1990, is projected to fall to 42.3 percent in 2015. Most countries have achieved universal primary enrollment rates of 90 percent or higher. The primary school completion rate has risen from 53 percent in 1993 to 70 percent in 2011.

Almost half the countries of Africa have achieved gender parity in school. The proportion of women in national parliaments has reached nearly 20 percent, a milestone that only developed countries and Latin America have achieved.

Improvements in health have been dramatic. The under-five mortality rate declined by 47 percent, from 146 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 91 deaths in 2011. Maternal mortality fell by 42 percent, from 745 deaths per 100,000 live births to 429 deaths over the same period. The once seemingly unstoppable HIV/AIDS rate has, in fact, been reversed, with prevalence rates dropping from 5.9 percent in 2001 to 4.9 percent in 2011. Tuberculosis and malaria remain serious problems, but their spread has been largely stopped.

U.S. Assistance to Africa: Writing the Next Chapter

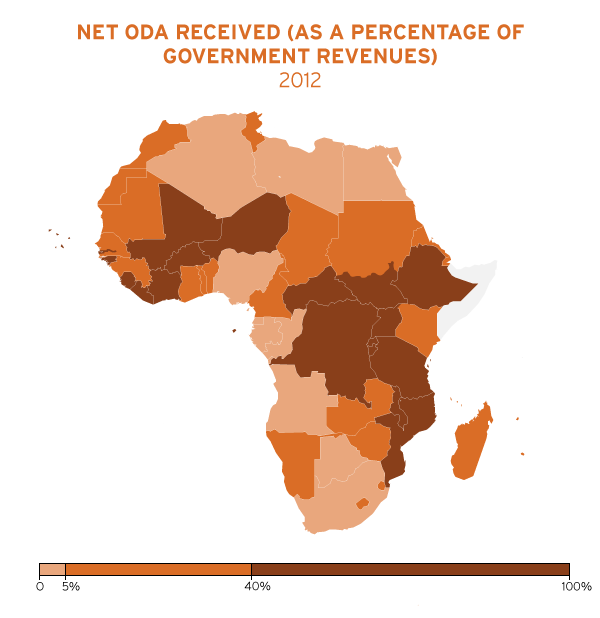

While external private investment flows have been a growing source of capital for Africa—a fivefold increase from major partners in the past decade as explained in a recent blog by my Brookings colleagues—for many countries in Africa foreign assistance remains an important source of development finance. One way to get a crude indication of the relative importance of foreign assistance is to compare it to the size of government revenues. The map below shows 20 countries in Africa for which total foreign assistance is equivalent to more than 40 percent of the national budget.

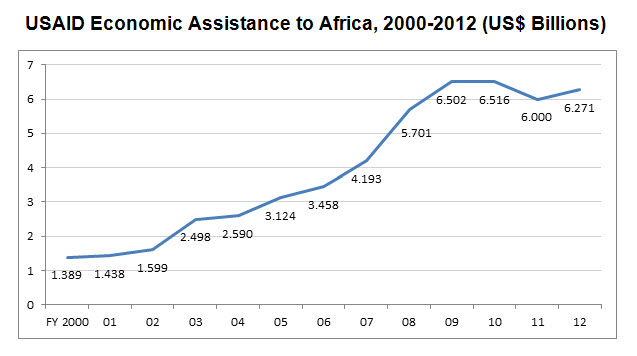

If one wonders whether Africa is a priority for U.S. assistance policy, just look at the numbers. At the 2005 Gleneagles Summit, the G-8 committed to increase assistance by $50 billion, half for Africa. The U.S. subsequently more than doubled its aid to Africa. Today, the U.S. and World Bank IDA (International Development Agency) vie as the largest donor to Africa, with shares at 17 percent of total assistance flows to Africa each. The next biggest donor is the European Union at 10 percent, followed by France, the United Kingdom and Germany, in that order. In fact, aid to Africa from European nations has declined the last several years while the U.S. has maintained its Gleneagles commitment.

The U.S. priority for Africa has grown over the past decade. In 2002 U.S. economic development assistance (not counting humanitarian assistance) to Africa was 17 percent of total U.S. economic assistance. That percentage has steadily grown over the past decade to 40 percent for both FY2014 (estimated) and the budget request for FY2015. The priority given to Africa is even more impressive when you consider that U.S. budget levels for foreign assistance peaked in 2010, in which year 32 percent of U.S. economic development assistance was devoted to Africa. Despite a decline of approximately 20 percent of budget levels for all development assistance from 2010 to 2014, the magnitude of assistance for Africa has remained above $6 billion per year, accounting for Africa’s continued rise in percentage of total U.S. economic development assistance.

As with the U.S., Africa is a rising priority for China As reported by Yun Sun in a companion blog, Africa represented 46 percent of Chinese aid in 2009 but 52 percent in 2010-2012. The major difference between U.S. and Chinese assistance to Africa is that Chinese assistance is principally for infrastructure and economic activities, with negligible amounts for humanitarian purposes, and is mostly loans. In contrast, U.S. assistance is concentrated in the social sectors and is almost all grants. In addition, the U.S. is the major provider of humanitarian assistance to Africa.

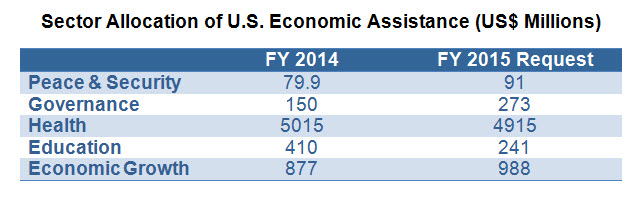

For the past decade, health has been the main focus of U.S. assistance to Africa, accounting for approximately 80 percent of total U.S. economic assistance in recent years. But after a decade of growth, that focus may be begin to change to reflect the 2012 White House strategy statement on U.S. policy toward Africa. That policy document emphasizes governance, economic growth and trade, and peace and security. The accompanying chart shows the proposed shift in funding into those accounts in the FY2015 budget request. Whether Congress will go along with that shift remains to be seen.

Power Africa

One particularly recent innovative U.S. program is Power Africa, announced by President Obama in June 2012. Some 600 million Africans live without electricity. The goal of the program is to double access to power in sub-Saharan Africa by adding 10,000 megawatts to output. The innovations in the program are multifold. Rather than the typical sequence of designing the program and then inviting in the private sector, the design started with canvassing the needs of private sector energy investors. Furthermore, the program joins together a focus on both governance and finance and operates across the U.S. government.

The initiative, led by USAID, involves 12 U.S. government agencies, some 40 private companies, and six African countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria and Tanzania). The U.S. government has committed $7 billion in financing over five years, and private companies have committed another $ 14 billion. Development of the program involved identifying specific private sector investments that have not moved beyond the planning phase because of inhospitable host government regulations and policies, or inaction, and/or insufficient financing. In addition to providing financing, the equally important part of the program is the effort to help remove restrictive host country policies and regulations, and institute policies that more rationally regulate and encourage private investment.

Interest in Power Africa has grown in the U.S. Congress since it was announced. Congress may even up the ante on the president. HR 2548 (Electrify Africa Act) passed the House on May 5, and the companion Senate bill S 2014 (Energize Africa Act), would double the goal of Power Africa to 20,000 megawatts.

The development story in Africa is still being written. The African leaders who come to Washington in early August will have a large voice in how that story plays out. There remain many causes for concern, but more reasons for optimism.

Let’s forget about pledging a host of deliverables and hope that the result of the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit is a frank exploration of the needs and potential for Africa, and a no-nonsense appraisal of how the U.S. can be most helpful. Let’s hope that the impact is to expand the priority that Africa holds for U.S. policy and show that this is a story in which the U.S. is determined to play its part.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit: Africa’s Dramatic Development Story

July 28, 2014