Saudi Arabia has sent both its king and his foreign minister on important foreign trips recently, as a key part of a significant diplomatic offensive to improve its strategic relations.

King Salman’s month-long trip to Asia, which began Sunday, is the most visible part of the offensive. He is traveling with a 600-strong entourage to Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, China, Japan, and the Maldives before attending the Arab League summit in Jordan at the end of March. It will be the first visit by a Saudi king to Indonesia since King Faysal in the 1970s and the first ever by a Saudi King to Japan.

Saudi royals often take long excursions outside the kingdom. Crown Prince Muhammad bin Nayef, for example, spent over a month in Algeria just a year ago. But those trips are private and involve little public diplomacy. King Salman is traveling with a much more public role. His entourage will actually grow on the trip to over 1,500.

An unspoken goal of such a lengthy trip is to demonstrate the king’s vitality and resilience. Salman turned 81 on December 31. Rumors about his health are endemic, especially about his mental acuity. A vigorous agenda will test him, so the court has included lengthy stops along the trip to provide plenty of time for rest. The Indonesian leg is 12 days, for example, and includes a stop in Bali.

Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei are important Muslim countries. All are potential allies in Saudi Arabia’s rivalry with its arch nemesis Iran. The Saudis have courted them to join its Islamic military alliance, which is directed against, Tehran although its official purpose is to fight terrorism.

China and Japan are crucial markets for Saudi oil. Again, Iran is a competitor for market share now that sanctions are gone. We can expect a host of new agreements will be announced at each stop in the month.

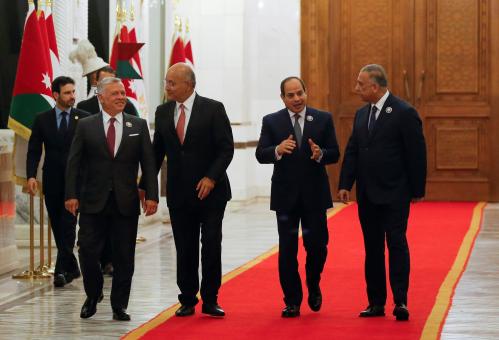

Foreign Minister Adel al Jubeir’s visit to Baghdad is more dramatic. It is the first visit by a senior Saudi official to Iraq since 1990. The last significant visit was by then-Saudi ambassador to the United States Prince Bandar bin Sultan. His mission was to try to mediate the growing tensions between Baghdad and Washington in the spring of 1990. Later that summer, Saddam seized Kuwait and threatened to invade Saudi Arabia. Twenty-seven years of American war in Iraq have followed.

Riyadh has long held that the 2003 American invasion of Iraq only served to advance Iranian interests by putting the Shiite Arab Iraqi majority in power. For years, the Saudis refused to open an embassy or send an ambassador to Baghdad, not wanting to give the government the legitimacy of recognition. When an ambassador was finally sent, he was recalled late last year after he berated the Iranian influence in Iraq and was said to be the target of assassination attempts.

So Jubeir’s visit to Iraq is a dramatic change in the Saudi approach. He has described his meeting with Prime Minister Abadi as positive, saying that the two countries agreed to work to fight terror together.

The Saudis have apparently decided to try a different approach to Iraq. They hope engaging with the Abadi government at a higher level will provide some counterweight to the Iranian influence in Baghdad. Riyadh is unlikely to ever have the influence Tehran enjoys with so much of the Shiite community, including militias and politicians—but it can have some influence.

The foreign minister’s trip is a long overdue acceptance of reality. The Sunni Arab minority in Iraq will not regain control of the country in the foreseeable future. The Saudi leadership was in denial about that reality for over a decade.

The Arab summit in Amman is a key meeting for the kingdom. It wants to showcase Arab unity and support for King Abdullah, an important ally facing a storm of challenges at home and abroad. A triumphant tour of Asia and a more flexible approach on Iraq are stepping stones to the Amman summit on March 27.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What’s behind Saudi Arabia’s new diplomatic offensives?

February 27, 2017